Introduction: When a Good Memory Becomes More Than Just a Talent

For many people, forgetting things is a frustrating and common experience. But for a select group, memory works like a finely tuned machine—names, dates, conversations, and even subtle sensory cues seem to stick with uncanny precision. If you’ve ever asked yourself, “Why is my memory so good?” you’re not alone. That question, while seemingly simple, taps into a complex web of brain functions, biological factors, and cognitive processes that neuroscientists are only beginning to fully understand. Having a good memory is often regarded as an enviable trait, but beyond being a source of pride or convenience, exceptional memory abilities can reveal a great deal about long-term brain health and overall cognitive function.

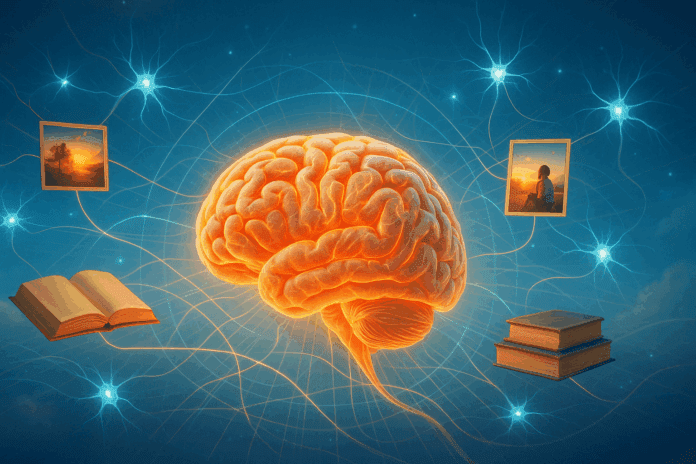

In today’s information-driven world, where productivity, academic performance, and even social interaction hinge heavily on cognitive sharpness, understanding what drives a good memory becomes not just a matter of curiosity, but of health relevance. Is it genetics? Environment? Diet? Emotional regulation? Perhaps all of these. The truth is that a strong memory is rarely the result of a single factor. Instead, it emerges from the dynamic interplay of neural plasticity, biochemical support, mental training, and lifestyle habits. From the hippocampus to the prefrontal cortex, and from neurotransmitters to sleep cycles, a good memory represents an integrated expression of the brain’s most vital systems functioning at their best.

In this article, we’ll explore the neurological underpinnings of strong memory, the surprising reasons some individuals retain and retrieve information with ease, and what it all suggests about mental resilience and brain longevity. We’ll also consider how science evaluates memory performance and whether there are ways to further enhance or protect your cognitive capabilities over time. Whether you’re someone who always remembers names or finds yourself recalling childhood events with vivid clarity, understanding the neuroscience of why your memory is so good can provide not only insight but also strategies to sustain and support your cognitive edge for years to come.

You may also like: What to Eat to Boost Memory: Science-Backed Brain Foods That Improve Recall, Focus, and Long-Term Mental Health

The Brain Regions Behind a Good Memory: Mapping the Neural Landscape

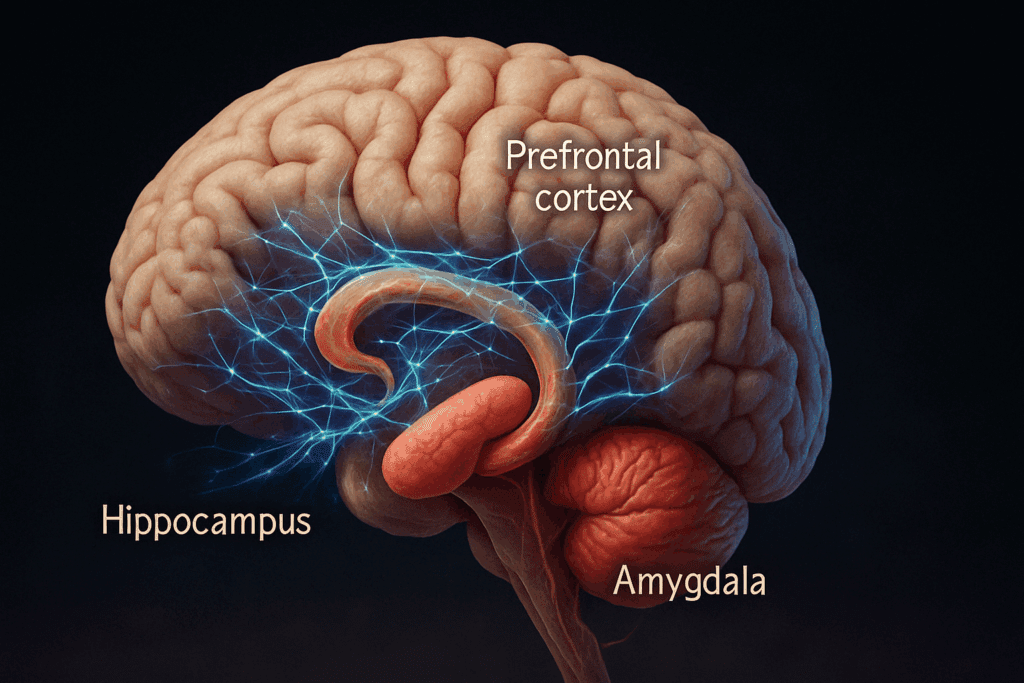

The science of memory starts with the brain’s architecture. When examining why some individuals have a good memory, neuroscientists first look to the specific regions most directly involved in memory encoding, storage, and retrieval. Chief among these is the hippocampus—a seahorse-shaped structure embedded deep within the temporal lobe. The hippocampus plays a central role in consolidating short-term memories into long-term ones and is particularly active during sleep, when memories are reinforced and reorganized. People with larger or more efficiently functioning hippocampi often demonstrate superior declarative memory, which encompasses facts and events.

However, the hippocampus doesn’t work alone. The prefrontal cortex, particularly the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, is heavily involved in working memory and executive function—essential components of staying focused and organizing information in real-time. This region helps you keep a phone number in mind long enough to dial it or remember where you parked your car. Efficient connectivity between the prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus allows for fluid information transfer, enhancing memory recall and decision-making speed.

The amygdala also contributes, especially when emotion-laden experiences are involved. This almond-shaped structure tags emotional relevance to memories, making them easier to recall later. A good memory is often characterized not only by the quantity of information retained but also by its vividness and emotional salience. Those with good memory may have a brain that is particularly adept at integrating sensory and emotional details into a coherent mental snapshot, making recall more robust and nuanced.

Importantly, recent studies using functional MRI have revealed that people with exceptional memory capabilities show enhanced connectivity between these brain regions, indicating that memory strength often hinges more on the quality of communication between regions than on their individual size or activity levels. This neural synergy allows for more efficient encoding and retrieval, suggesting that when someone wonders, “Why is my memory so good?”, part of the answer may lie in how harmoniously their brain regions cooperate during memory-related tasks.

Neurochemistry and Cognitive Performance: The Role of Neurotransmitters in Memory

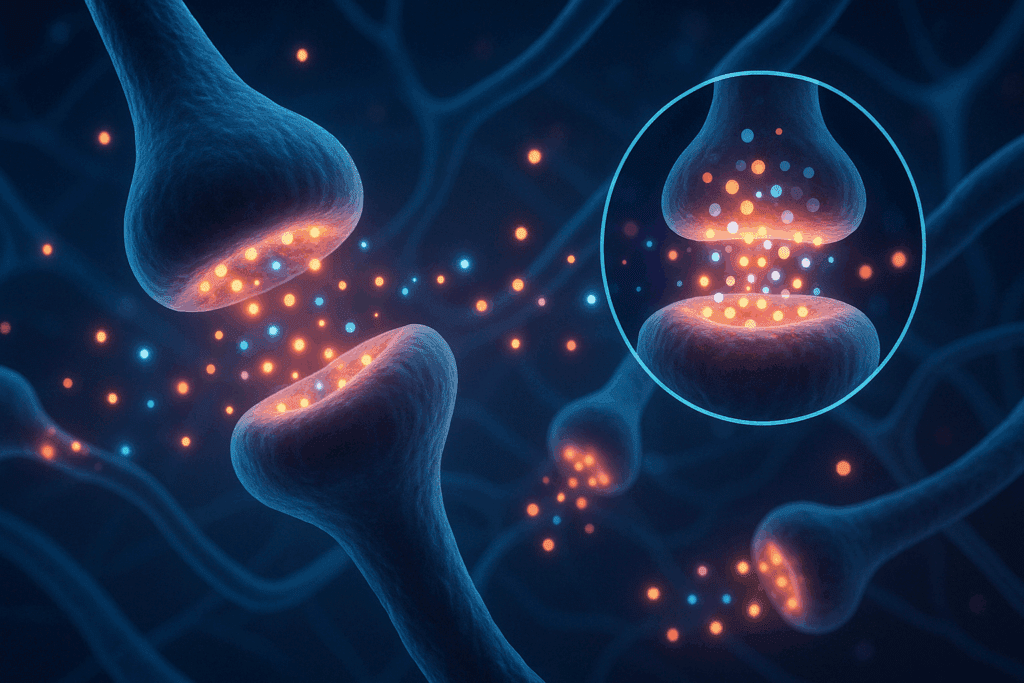

While the brain’s physical structure lays the groundwork for memory function, its chemical environment significantly influences how well that structure operates. Neurotransmitters—the brain’s chemical messengers—are essential for transmitting signals between neurons, and several play crucial roles in memory and learning. Chief among them is acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter heavily involved in attention, learning, and memory. High levels of acetylcholine activity, particularly in the hippocampus and cortex, are associated with improved memory consolidation and retrieval. It’s no coincidence that many medications used to treat memory loss in Alzheimer’s disease aim to boost acetylcholine levels.

Another key player is dopamine. Often associated with reward and motivation, dopamine enhances memory by promoting focus and encouraging the brain to prioritize and store information that is deemed valuable or relevant. When you’re interested or emotionally engaged in a topic, dopamine helps flag that information for better retention. This can partially explain why people with a good memory often describe themselves as intensely curious or intrinsically motivated learners.

Norepinephrine, a neurotransmitter linked to arousal and alertness, also contributes by increasing attention and facilitating the encoding of emotionally significant memories. It works closely with the amygdala to ensure that moments of fear, excitement, or surprise are logged with greater intensity, enhancing long-term recall. In contrast, deficiencies or dysregulations in these neurotransmitter systems can lead to forgetfulness, poor attention span, or fragmented memory formation.

Additionally, the brain’s neurochemical balance is profoundly influenced by lifestyle factors such as diet, exercise, and stress levels. For instance, chronic stress floods the brain with cortisol, which over time can impair hippocampal function and weaken memory. Conversely, physical exercise has been shown to increase levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein that supports the growth and survival of neurons, especially in memory-critical areas like the hippocampus. Therefore, when contemplating why your memory is so good, it may be worth considering the internal biochemical orchestra that enables neurons to fire effectively and store information with precision.

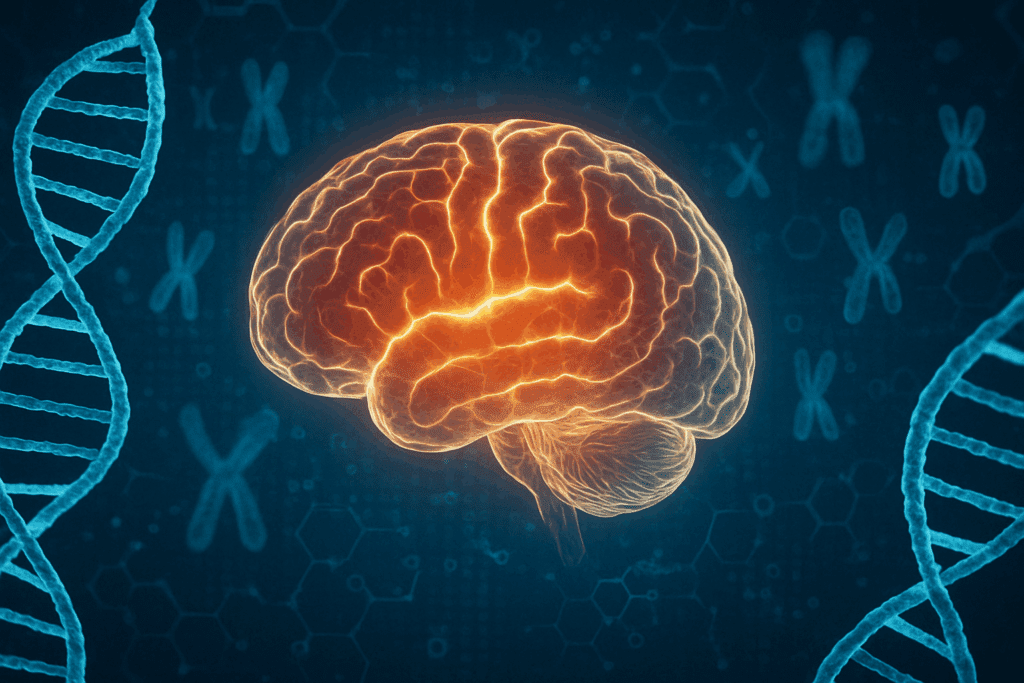

Genetic Factors and Inherited Cognitive Traits: Are You Born with a Good Memory?

Genetics undeniably play a foundational role in determining cognitive potential, including memory capabilities. Research into the heritability of memory has revealed that certain genetic profiles are associated with superior memory performance. For instance, variations in genes related to dopamine regulation (like COMT) and brain plasticity (like BDNF) can influence how efficiently information is processed, stored, and recalled. These genetic traits may predispose some individuals to enhanced memory function from an early age.

Twin studies provide some of the strongest evidence for a genetic component to memory. Identical twins often show more similar memory performance compared to fraternal twins, suggesting that memory abilities are significantly heritable. However, genetics rarely act in isolation. Even if someone inherits a predisposition for a good memory, environmental influences and personal habits can either enhance or diminish that innate advantage. This interplay underscores the concept of epigenetics, where gene expression is modified by lifestyle factors such as nutrition, cognitive stimulation, and emotional health.

Moreover, not all aspects of memory are equally heritable. For example, working memory and long-term episodic memory may be influenced by different genetic mechanisms. Someone might excel at recalling detailed events but struggle with multitasking or short-term information retention. This variation supports the idea that asking “Why is my memory so good?” requires a nuanced understanding of which type of memory is strong and what underlying genetic mechanisms support that function.

Interestingly, researchers have also identified a subset of people known as Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory (HSAM) individuals, who can recall virtually every day of their lives in extraordinary detail. Although still under study, this phenomenon appears to have both structural and genetic components, suggesting that extreme memory abilities are not solely the result of training or interest, but may arise from distinct neurobiological and hereditary factors. If you’ve ever wondered why your memory stands out in comparison to others, there’s a good chance your genes have helped lay the foundation.

Cognitive Habits and Lifestyle Patterns That Reinforce a Good Memory

While genetics and brain structure may provide the scaffolding, lifestyle habits are what ultimately shape and reinforce memory performance over time. People with a good memory often engage in mental routines and behaviors that naturally support cognitive function. These habits may include regular reading, mindfulness practices, strategic repetition, or mentally challenging hobbies like chess, writing, or learning new languages. The brain, much like a muscle, thrives on stimulation. Engaging it regularly in focused and diverse ways can strengthen neural circuits involved in memory consolidation and retrieval.

Sleep is another crucial, often underestimated, pillar of memory health. During deep sleep stages—particularly slow-wave and REM sleep—the brain undergoes memory consolidation, transferring information from the hippocampus to the cortex for long-term storage. Studies have shown that even a single night of poor sleep can disrupt this process, while consistent, high-quality sleep dramatically enhances memory accuracy and detail. People who routinely wake up feeling refreshed and mentally sharp are more likely to exhibit good memory performance simply because their brains have had the necessary time to encode and integrate information effectively.

Nutrition also plays a key role. Diets rich in omega-3 fatty acids, antioxidants, and B vitamins have been shown to support brain health, particularly in regions involved with memory and learning. Foods like fatty fish, leafy greens, blueberries, and nuts are often associated with improved cognitive outcomes. Hydration is equally important; even mild dehydration can impair attention and short-term memory. Many individuals with strong cognitive abilities report being intentional about what they eat, when they eat, and how they manage energy levels throughout the day.

Stress management rounds out the lifestyle equation. Chronic stress not only increases cortisol but also shrinks the hippocampus over time, directly impairing memory formation and recall. Techniques like deep breathing, yoga, and regular physical activity can help maintain emotional balance and reduce cognitive load. Ultimately, those who ask “Why is my memory so good?” may benefit from evaluating their daily routines—not as afterthoughts, but as active contributors to mental clarity and brain longevity.

Age and Memory: Why Some Minds Stay Sharp Across the Lifespan

Aging is often associated with a decline in cognitive abilities, yet many individuals maintain a good memory well into their later years. This discrepancy raises important questions about what differentiates normal age-related forgetfulness from enduring mental sharpness. Research in geriatric neuroscience has shown that memory decline is not inevitable. In fact, a significant number of older adults demonstrate what scientists call “cognitive resilience”—the brain’s ability to adapt and function despite age-related changes or even early-stage neurodegenerative conditions.

One of the key factors in this resilience appears to be cognitive reserve. This concept refers to the brain’s capacity to efficiently use its existing networks or develop new ones to compensate for damage or aging. People with a higher cognitive reserve—often the result of a lifetime of education, intellectual engagement, social interaction, and healthy living—are more likely to preserve a good memory as they age. In essence, the brain develops alternate routes for accessing stored information, making memory loss less noticeable or impactful even when some structural decline is occurring.

Moreover, neuroimaging studies have identified that older adults who retain good memory abilities tend to have greater cortical thickness in specific areas of the brain, particularly in the medial temporal lobe and prefrontal cortex. These findings suggest that structural integrity, when supported by lifestyle and mental stimulation, can significantly delay or even prevent cognitive decline. Additionally, regular physical activity has been linked to increased hippocampal volume in aging adults, reinforcing the notion that proactive habits can preserve memory across the lifespan.

Interestingly, psychological traits like optimism, purpose in life, and stress resilience also play a role in memory maintenance. Seniors who report high levels of psychological well-being tend to perform better on memory tasks, highlighting how emotional health and brain health are interconnected. If you’re wondering why your memory is so good even as you age, it may be that your life experiences, routines, and inner outlook have collectively built a strong cognitive foundation that continues to support mental clarity over time.

Enhancing Memory Through Evidence-Based Cognitive Strategies

While some individuals naturally exhibit a good memory, research has shown that memory performance can be meaningfully improved through deliberate mental training and behavioral techniques. The human brain is remarkably adaptable—a quality known as neuroplasticity—which means that it can form new neural connections throughout life in response to experience, learning, and practice. Cognitive training programs designed to challenge memory and executive functions have shown promising results in both young adults and older populations, suggesting that even high-functioning minds can benefit from structured exercises aimed at optimizing mental acuity.

One of the most effective techniques for enhancing memory is spaced repetition. This method involves reviewing information at gradually increasing intervals, a pattern that aligns with how the brain naturally consolidates and stores long-term memories. Spaced repetition leverages the “forgetting curve,” a psychological model that describes how memories fade over time without reinforcement. By intentionally re-engaging with information before it is forgotten, individuals can dramatically increase retention and recall. This strategy is especially popular among students, language learners, and professionals seeking to retain large volumes of knowledge efficiently.

Another powerful approach is the use of mnemonic devices—mental shortcuts that help encode information through association. Techniques such as acronyms, visual imagery, and the method of loci (also known as the memory palace) capitalize on the brain’s preference for patterns, spatial relationships, and multisensory input. These tools are not merely tricks; they are grounded in decades of cognitive science that highlight how associative memory can be harnessed to make complex information more memorable.

Meditation and mindfulness practices have also gained recognition for their cognitive benefits, including improvements in working memory, attention, and emotional regulation. Mindfulness training strengthens the brain’s ability to stay focused on the present moment, which is crucial for encoding new information effectively. By reducing mind-wandering and promoting a calm, attentive state, mindfulness enhances the brain’s capacity to absorb and retain meaningful details. For those asking “Why is my memory so good?” the answer may lie not only in what they remember but also in how they cultivate the mental conditions that support memory formation in the first place.

Importantly, these cognitive strategies are not mutually exclusive. In fact, their effects can be amplified when combined with other healthy habits such as sleep optimization, proper nutrition, and regular physical exercise. By engaging the brain on multiple levels—intellectually, emotionally, and physically—individuals can create a synergistic environment in which memory thrives.

Emotion, Attention, and Memory: Why We Remember What Moves Us

Among the most fascinating aspects of memory is its selectivity. We forget hundreds of mundane details each day, yet we vividly recall the moment we received life-changing news, heard a powerful song, or experienced an emotionally charged conversation. The reason behind this selectivity lies in the deep entanglement of emotion and attention with memory formation. These two cognitive forces serve as gatekeepers, signaling to the brain which experiences are worth encoding deeply and which can be discarded without consequence. Understanding how emotion and attention affect memory can help us appreciate why some people seem to retain information more vividly than others—and why some memories stay with us forever.

Emotionally charged events trigger a cascade of biochemical and neurological responses that influence memory processing. When you experience a strong emotion, the amygdala becomes highly active and interacts with the hippocampus to strengthen the memory trace. This dual activation results in the encoding of richer, more detailed memories. For example, a joyful wedding day or a traumatic accident often becomes etched into our minds with extraordinary clarity, not because the event was objectively important, but because the emotional weight attached to it heightened our brain’s ability to record it. This mechanism also explains phenomena like “flashbulb memories,” where emotionally significant moments are remembered as if they were snapshots frozen in time.

Attention, meanwhile, acts as the brain’s spotlight. It determines which stimuli are noticed and processed and which are ignored. In our increasingly distracted world, the ability to maintain focused attention has become a rare and valuable asset—one closely linked to good memory. Neuroscience has shown that when attention is fully engaged, neural activity in memory-related regions like the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex becomes more synchronized, enhancing the likelihood of accurate recall. This is particularly evident during learning: information studied with undivided attention is far more likely to be retained than information absorbed passively or amid distractions.

The interplay between emotion and attention is especially powerful. Emotional experiences naturally command our attention, leading to better encoding. Similarly, when we deliberately pay close attention to something—because it’s meaningful, urgent, or rewarding—our emotional engagement with it often increases. This feedback loop can result in particularly strong memories. For individuals who frequently experience deep emotional resonance or exhibit high attentional control, these mechanisms may explain why their memory is so good.

In therapeutic settings, this connection has also been harnessed to help reshape or reframe difficult memories, particularly in trauma recovery. Techniques like Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) rely on the targeted engagement of attention and emotion to help reconsolidate memories in a less distressing way. This application underscores how malleable memory is—and how central emotion and attention are to its structure.

If you find yourself recalling past experiences with remarkable clarity, consider how often your memory is tied not just to facts, but to feelings. Recognizing this connection can deepen your understanding of your own cognitive strengths and offer new pathways for enhancing memory through emotional awareness and focused presence.

Memory, Identity, and Mental Health: How a Good Memory Shapes the Self

Memory is not merely a repository for facts and experiences; it is the foundation of selfhood. Every story we tell about who we are—our preferences, relationships, values, and aspirations—is informed by the memories we hold. When we ask, “Why is my memory so good?” we’re not just marveling at cognitive prowess; we’re also recognizing a deeper sense of connection to the experiences that have shaped our personal narrative. In this way, memory functions as the scaffolding upon which our identity is built, and disruptions to memory often lead to profound psychological effects that reach far beyond simple forgetfulness.

Autobiographical memory plays a crucial role in this process. It allows us to organize our life experiences into a coherent timeline, providing a sense of continuity and meaning. People with a good memory often have an enhanced ability to reflect on past events in rich detail, allowing them to draw insights from previous challenges and victories. This capacity strengthens emotional resilience, as it creates a mental archive of successful coping strategies and joyful moments that can be revisited in times of distress. Such a process not only fortifies identity but also fosters emotional intelligence and self-awareness.

Creativity, too, is intimately linked with memory. Far from being a linear process of retrieval, memory is dynamic and reconstructive. The brain does not simply replay past events—it reinterprets, reshuffles, and blends them with imagination and new information to produce original ideas. Artists, writers, and inventors frequently describe their creative process as one rooted in memory, drawing upon vivid recollections or subtle fragments of past experiences to generate novel work. A good memory provides a rich mental library from which to draw inspiration, allowing for deeper, more nuanced creative expression.

On the other hand, mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) often involve maladaptive memory processes. Depressed individuals may ruminate on negative memories or have difficulty recalling positive events, while those with PTSD may experience intrusive recollections that disrupt daily functioning. These examples underscore how tightly memory is woven into emotional regulation and psychological well-being. Conversely, people with a good memory that includes balanced emotional encoding—able to remember positive and neutral events as clearly as negative ones—may enjoy greater mental stability and emotional flexibility.

Moreover, a well-functioning memory system contributes to healthy interpersonal relationships. Remembering names, faces, shared experiences, and emotional nuances enables us to form deeper connections with others. It builds trust, intimacy, and social cohesion. In contrast, memory impairments often lead to social withdrawal, frustration, or misunderstandings, highlighting memory’s role in the social fabric of human life. Individuals who wonder why their memory is so good may recognize that this ability enhances not only their intellectual capabilities but also the depth and quality of their human relationships.

Ultimately, memory serves as the link between past, present, and future. It informs decision-making, predicts consequences, and allows us to learn from experience. In this light, having a good memory is not just a sign of mental efficiency—it is a marker of psychological integration, personal growth, and adaptive functioning. When viewed through this lens, memory becomes less about recall and more about meaning, reminding us that what we remember shapes who we are, how we connect with others, and how we move forward in life.

Digital Technology and the Modern Brain: Does a Good Memory Still Matter in the Information Age?

In an era when nearly every fact, date, or image is accessible with a quick online search, the role of human memory is undergoing a profound transformation. Smartphones, voice assistants, and cloud storage have allowed us to offload many cognitive responsibilities, freeing our minds from the burden of memorizing phone numbers, appointment dates, or directions. This phenomenon, often referred to as “cognitive offloading,” has raised important questions: Does a good memory still matter in the digital age? And if you find yourself with unusually sharp recall, what does that say about how your brain is adapting—or resisting—these technological shifts?

To begin with, it’s crucial to recognize that while digital tools offer convenience, they also come at a cognitive cost. Studies in cognitive neuroscience have shown that the frequent use of digital devices may reduce our reliance on internal memory systems. This can result in what’s known as the “Google effect,” a tendency to forget information that is easily accessible online. In this context, our brains adapt by remembering where to find information rather than what the information is—a shift from declarative memory to metacognitive awareness. While this may seem efficient, it potentially weakens neural pathways related to deep learning, critical thinking, and long-term retention.

Despite these trends, individuals with a good memory often report using technology as a supplement rather than a substitute for internal recall. They may still rely on calendars or notes, but they continue to engage actively with the information they encounter—processing it, analyzing it, and connecting it with existing knowledge. This deliberate cognitive engagement helps reinforce neural connections, ensuring that the brain remains actively involved in learning rather than becoming passive or dependent. In this way, people with strong memory function seem to thrive not because they avoid technology, but because they use it strategically, balancing digital support with mental effort.

Additionally, multitasking—a hallmark of digital life—has been found to impair memory encoding. Constant notifications, rapid task-switching, and the habit of skimming rather than reading deeply can scatter attention and interfere with the formation of meaningful memory traces. Sustained focus is critical for encoding information into long-term memory, and distractions fragment this process. Yet, individuals with a good memory often exhibit high levels of attentional control, resisting the lure of constant digital stimulation. They may intentionally carve out distraction-free time for reflection, reading, or conversation—habits that support the consolidation of knowledge and the maintenance of cognitive clarity.

That said, technology isn’t inherently detrimental to memory. In fact, digital tools can also be used to enhance memory if integrated wisely. Apps that utilize spaced repetition, brain-training games, or platforms for learning new skills offer ways to exercise memory systems rather than bypass them. Virtual reality and immersive learning environments are also being studied for their potential to strengthen memory by engaging multiple senses simultaneously, thus mimicking the brain’s natural preference for rich, multisensory experiences.

The key lies in intentional use. Those who ask “Why is my memory so good?” in the modern world may be unconsciously practicing digital mindfulness—choosing to engage deeply with information, avoiding excessive multitasking, and using technology to reinforce rather than replace memory. In this context, a good memory becomes not just a personal trait but a conscious lifestyle—a commitment to attention, depth, and mental independence in a time when the temptation to outsource thinking is stronger than ever.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Why do emotionally significant memories seem easier to recall?

Emotionally intense experiences are often remembered more vividly because the brain prioritizes emotionally charged information. The amygdala, which processes emotion, activates alongside the hippocampus during emotional events, enhancing the encoding of those memories. If you’ve ever asked yourself, “Why is my memory so good when it comes to emotional events?” the answer may lie in this neural synergy. This explains why people with a good memory can often recount highly emotional moments in detail. Understanding how emotional salience works helps clarify why some memories have an almost cinematic quality, especially when compared to mundane, everyday occurrences.

2. Can having a good memory sometimes lead to mental fatigue?

Yes, having a good memory can be both a strength and a challenge. Constant recall of detailed memories, especially negative or emotionally charged ones, may contribute to cognitive overload or emotional exhaustion in some individuals. Those who wonder “Why is my memory so good, yet sometimes draining?” may be experiencing the cost of hyper-recall, where the brain struggles to filter unimportant memories. People with excellent memory capabilities often have to actively practice mental boundaries or mindfulness to prevent memory-related stress. In some cases, therapists even help clients with memory mastery learn how to manage mental boundaries.

3. Are people with a good memory more resistant to misinformation?

Interestingly, individuals with a good memory are often better at identifying and resisting misinformation. This is because strong memory supports better pattern recognition and contextual reasoning, allowing for more accurate information filtering. However, the downside is that those with excellent recall can also remember incorrect facts just as vividly if they are emotionally or socially reinforced. So, if you’re wondering, “Why is my memory so good but occasionally misleading?” the culprit might be initial exposure to misleading content. Being aware of this nuance is essential in a world of information overload and frequent disinformation.

4. How does physical activity influence memory strength?

Regular aerobic exercise increases blood flow to the brain and stimulates the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which supports neuron survival and synaptic plasticity. People who exercise consistently often report stronger recall, quicker learning, and more mental energy. If you’ve ever thought, “Why is my memory so good lately?” and recently adopted a workout routine, that’s no coincidence. Physical activity enhances both short-term and long-term memory functions, especially when combined with good sleep and nutrition. This holistic effect contributes to a more resilient cognitive system in the long run.

5. Does multilingualism enhance the ability to form a good memory?

Multilingual individuals are often better at tasks involving working memory, attention switching, and executive function. Learning and speaking multiple languages creates new neural pathways and improves cognitive flexibility. If you’re wondering, “Why is my memory so good in problem-solving or learning?” multilingualism could be playing a hidden role. Constantly navigating between linguistic systems helps strengthen memory encoding and retrieval. This cognitive advantage extends across a lifetime, often providing a buffer against age-related memory decline.

6. Can certain types of creative activities help maintain a good memory?

Yes, creative practices like painting, writing, and playing music can enhance memory by engaging multiple regions of the brain simultaneously. These activities involve a blend of motor skills, pattern recognition, emotional engagement, and sensory processing, all of which stimulate memory-related brain circuits. People who often reflect, “Why is my memory so good when I engage in creative tasks?” may be benefiting from this multisensory integration. Over time, creative expression also helps consolidate complex information into memorable forms. Engaging in the arts can thus be a preventive measure against cognitive decline.

7. Is a good memory linked to better decision-making skills?

Memory plays a pivotal role in how we assess risk, recognize patterns, and learn from past experiences—all of which are essential for sound decision-making. When individuals ask, “Why is my memory so good during critical thinking or debates?” they may be drawing from an enriched mental archive that allows for fast, context-sensitive judgments. People with good memory often simulate future outcomes based on past data, which improves strategic planning. This cognitive agility can be particularly valuable in professional environments that require quick yet informed decisions. Long-term, it supports career success and problem-solving resilience.

8. Do people with a good memory experience dreams differently?

Emerging sleep research suggests that individuals with a good memory may experience more vivid or coherent dreams. This is likely due to more robust memory consolidation during REM sleep, where emotional and declarative memories are reorganized. If you’ve ever wondered, “Why is my memory so good and my dreams unusually vivid?” there could be a meaningful connection. Some people even report lucid dreaming abilities linked to memory recall. Maintaining healthy sleep hygiene strengthens this nightly process, further enriching both memory and dream quality.

9. How does social interaction contribute to maintaining a good memory?

Social engagement exercises multiple cognitive skills at once—language, emotional interpretation, attention, and memory. Interacting regularly with others helps reinforce memory pathways by stimulating storytelling, emotional bonding, and real-time feedback. People who ask, “Why is my memory so good in conversations or group settings?” are likely benefiting from this social cognitive stimulation. Conversations often trigger associative recall and reinforce memory through repetition. Moreover, strong social bonds reduce stress, which also protects the brain from memory degradation.

10. What emerging technologies support individuals with a good memory in optimizing performance?

New advancements in wearable neurofeedback devices, memory-enhancing apps, and virtual reality are helping people refine and measure memory capacity more precisely. Those with a good memory can use these tools to track performance, challenge their limits, and even optimize attention cycles. If you’re exploring “Why is my memory so good and how can I take it further?” technologies like EEG-based biofeedback can help train the brain for even better recall. These innovations are expanding the possibilities for cognitive enhancement beyond traditional methods. Future developments may even tailor memory training programs to individual neurological profiles for highly personalized results.

Conclusion: What a Good Memory Says About Your Brain Health and How to Sustain It Over Time

In a world increasingly shaped by information overload and cognitive shortcuts, the presence of a good memory is more than a fortunate anomaly—it’s a powerful indicator of robust brain health, emotional intelligence, and long-term cognitive resilience. When you find yourself asking, “Why is my memory so good?”, you’re not simply marveling at a mental party trick. You are, in fact, acknowledging a complex, finely tuned network of biological, psychological, and behavioral systems working together in harmony. From the microcircuitry of the hippocampus to the chemical signaling of neurotransmitters, and from inherited genetic traits to daily lifestyle habits, a good memory reflects a state of neurological equilibrium that deserves both recognition and preservation.

What sets exceptional memory apart is not just recall volume, but the richness, clarity, and accessibility of stored information. Individuals with good memory tend to show enhanced connectivity between key brain regions, efficient use of attention and emotional salience, and an ability to integrate past experiences into present-day decision-making. These capacities provide more than just intellectual convenience—they offer stability in times of stress, insight in times of uncertainty, and a deeper connection to one’s identity and relationships. In this way, memory is both a tool and a mirror, reflecting how we think, feel, and ultimately live.

At the same time, the science is clear: memory is malleable. While some individuals may have a natural advantage, cognitive research continues to show that memory strength can be supported, cultivated, and even enhanced through conscious effort. Practices like mindfulness, quality sleep, aerobic exercise, and strategic learning techniques all contribute to the neurochemical environment necessary for optimal memory function. These strategies not only reinforce existing strengths but also serve as a buffer against age-related cognitive decline. Even in a digital world that increasingly encourages mental outsourcing, the choice to engage deeply with information, people, and experiences remains a powerful way to preserve cognitive vitality.

Perhaps most importantly, a good memory is not just about remembering facts—it’s about enriching the human experience. It allows us to hold onto the lessons we’ve learned, the people we’ve loved, and the lives we’ve lived. It gives us the ability to reflect meaningfully on our past, stay grounded in the present, and plan wisely for the future. In this sense, the question “Why is my memory so good?” becomes a doorway into a deeper appreciation of what it means to be mentally well—not only in terms of brain health, but in how memory anchors us to a life of awareness, continuity, and purpose.

As neuroscience continues to uncover the intricacies of memory, one truth remains constant: preserving and honoring this essential cognitive function is one of the most profound investments we can make in our lifelong mental well-being. If you are fortunate enough to have a good memory, nurture it—not only as a gift, but as a reflection of a brain that is engaged, healthy, and profoundly human.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out.

Further Reading:

Why Do We Remember? Study Explores the ‘Why’ Behind Human Memory

Why We Forget and How To Remember Better: The Science Behind Memory