A sudden, cramping pain in the lower abdomen accompanied by bloating, irregular bowel habits, or urgency can signal a spastic colon attack. This distressing gastrointestinal event is often misunderstood, both by the public and sometimes even within the medical community. While spastic colon syndrome is frequently associated with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), the terms are not completely synonymous. Understanding what causes these attacks, how they manifest, and what treatments are available is essential for those who suffer from the condition and for health professionals striving to provide relief.

You may also like: How Gut Health Affects Mental Health: Exploring the Gut-Brain Connection Behind Anxiety, Mood, and Depression

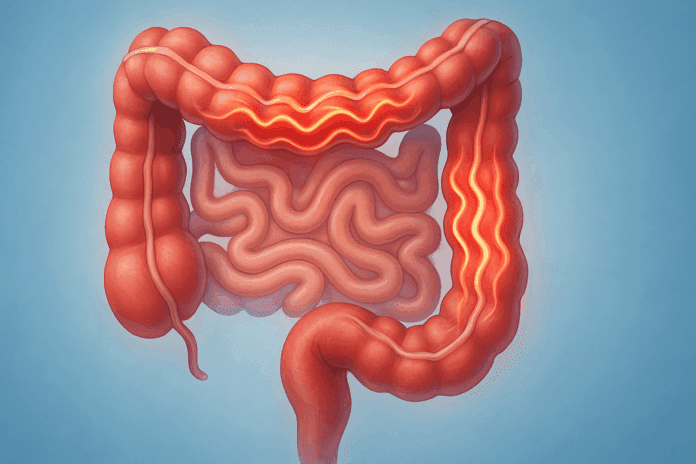

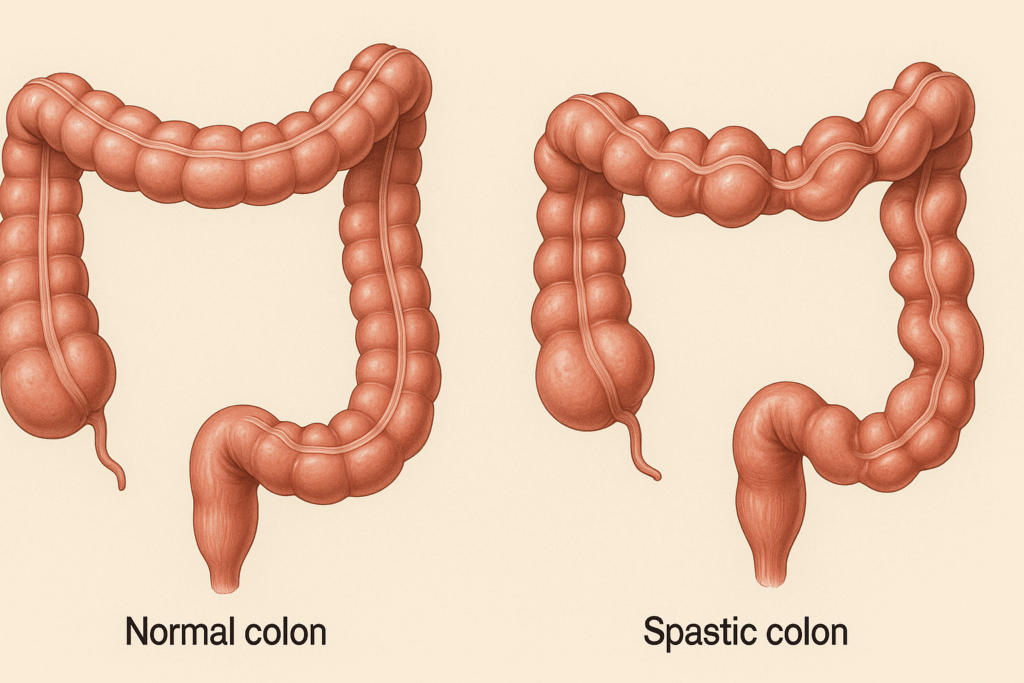

The term “spastic colon” has historically been used to describe a collection of gastrointestinal symptoms rooted in abnormal colon motility. It typically refers to a hyper-reactive or overly sensitive colon that contracts irregularly and sometimes violently. These contractions, or colon spasms, can lead to significant discomfort and disruption of daily life. A spastic colon attack is more than a simple stomach ache; it involves a series of muscular spasms that disturb the digestive rhythm and can induce a wide range of symptoms.

Distinguishing Spastic Colon from Other Gastrointestinal Disorders

Before delving into what causes spastic colon attacks, it’s crucial to distinguish this condition from other gastrointestinal disorders. Spastic colon is often equated with irritable bowel syndrome, but the two terms are not fully interchangeable. IBS encompasses a broader diagnostic category that includes not only colon spasms but also alterations in bowel habits, sensitivity to specific foods, and a complex interplay of neurological and psychological factors. Spastic colon, in contrast, specifically emphasizes the motor disturbances in the large intestine.

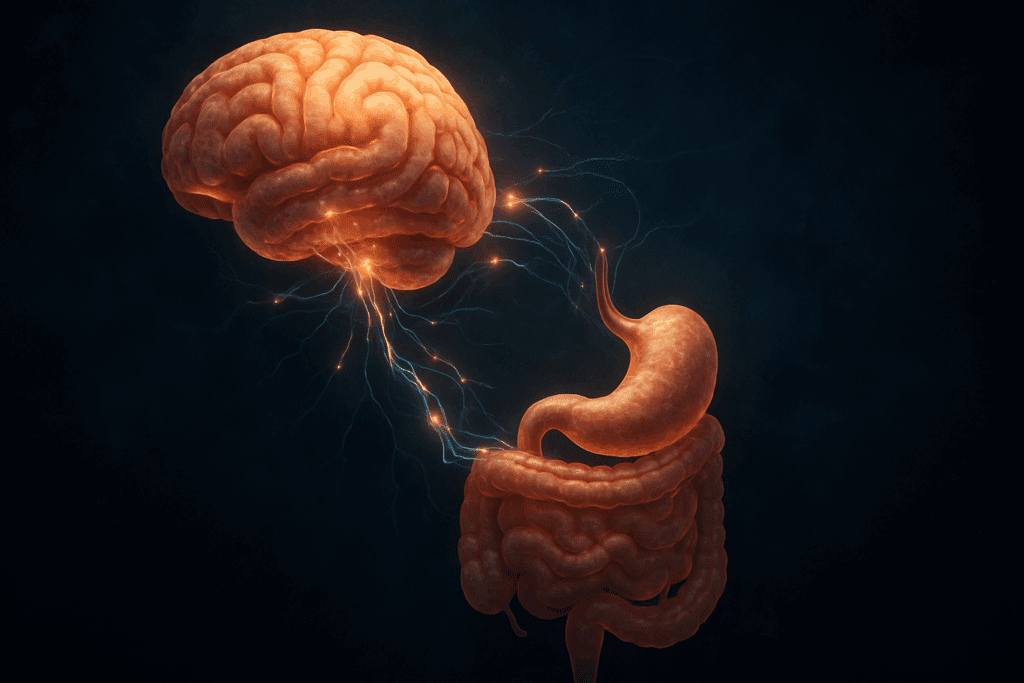

This distinction matters because while both spastic colon and IBS share symptoms such as bloating, abdominal pain, and irregular stool patterns, IBS is more comprehensively understood as a biopsychosocial disorder. The central nervous system plays a significant role in IBS, influencing gut sensitivity and motility through the gut-brain axis. In contrast, spastic colon describes a more mechanical dysfunction: the erratic muscular contractions that characterize colon spasm episodes. However, in practice, many people with a spastic colon are also diagnosed with IBS, making the clinical picture complex.

Recognizing the Symptoms of Colon Spasms

The symptoms of a spastic colon can vary in intensity and presentation from person to person, but most involve recurring episodes of colon cramps, abdominal discomfort, and changes in bowel movement frequency or consistency. These colon spasms symptoms often include alternating episodes of diarrhea and constipation, particularly in the IBS-mixed subtype. Gas, bloating, and an urgent need to defecate are also common features of a spastic colon attack.

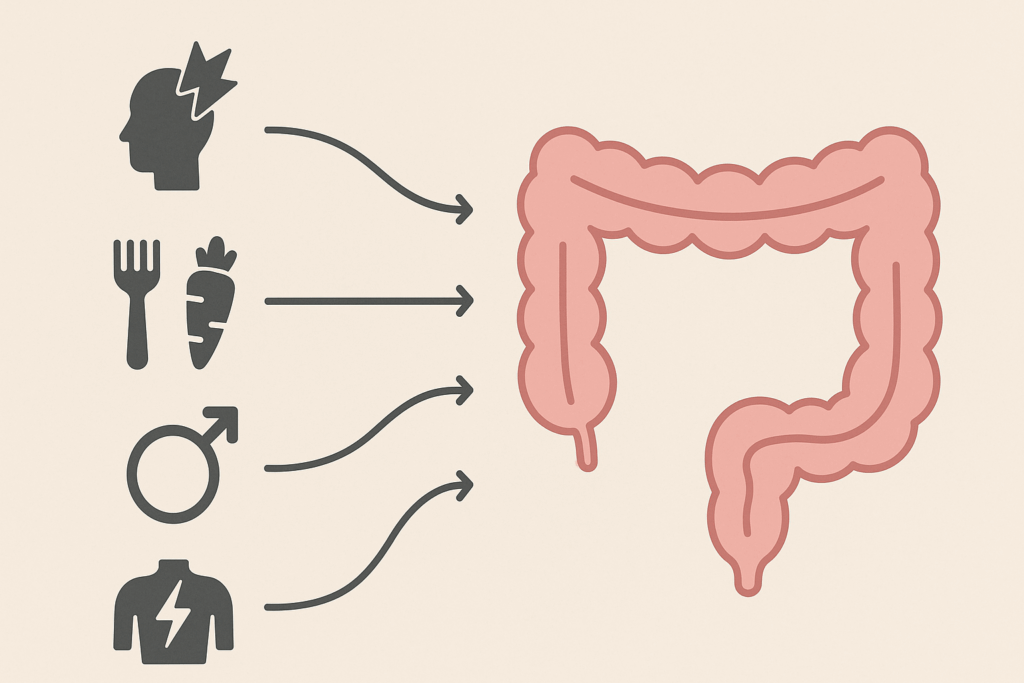

What sets colon spasms apart from typical digestive discomfort is the presence of sharp, wave-like abdominal pain that corresponds with irregular muscle contractions in the colon. These spasms can be brief and episodic or persist over an extended period. They are often triggered by dietary choices, stress, hormonal fluctuations, or even subtle shifts in the gut microbiota. For many, these attacks are unpredictable, leading to anxiety and the avoidance of social situations, which only amplifies the psychosomatic component of the condition.

In some cases, the condition may be mistaken for more severe disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or colorectal cancer. However, spastic colon symptoms typically lack the systemic signs—such as fever, unintended weight loss, or blood work abnormalities—that accompany those conditions. Nonetheless, the similarity in symptoms can create diagnostic confusion, making professional medical evaluation essential.

The Role of Stress and the Gut-Brain Axis

Modern research into gastrointestinal health increasingly emphasizes the central role of the gut-brain axis—a bidirectional communication pathway between the nervous system and the digestive tract. For individuals suffering from spastic bowel issues, psychological stress is not just a contributing factor but often a primary trigger for flare-ups. The colon, rich in nerve endings and deeply integrated into the autonomic nervous system, responds acutely to emotional states.

Stress and anxiety can provoke changes in the neurotransmitters that regulate colon function, such as serotonin and norepinephrine. These chemical messengers influence how the colon contracts and how pain signals are processed. In individuals with a sensitive gut, this can result in overactive muscular contractions, or colon spasms, leading to the hallmark symptoms of a spastic colon attack. This helps explain why mental health conditions like generalized anxiety disorder and depression frequently co-occur with spastic bowel syndromes.

Addressing the gut-brain axis is often central to treatment. Cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness-based stress reduction, and even gut-directed hypnotherapy have shown promise in reducing both the frequency and severity of spastic colon attacks. These therapies not only lower stress but may also recalibrate the way the brain interprets digestive discomfort. In this way, treating the mind can be an effective way of soothing the body.

Dietary Triggers and the Role of Gut Sensitivities

While psychological stress is a well-documented cause of colon spasms, dietary factors are no less influential. For many individuals, specific foods can act as triggers, initiating a cascade of events that culminate in a spastic colon attack. Common culprits include high-fat meals, caffeine, carbonated beverages, alcohol, and artificial sweeteners such as sorbitol or mannitol. These substances may increase intestinal gas, speed up or slow down motility, or provoke local irritation in the colon.

The low-FODMAP diet, which restricts fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols, has emerged as a promising approach for managing spastic colon symptoms. These carbohydrates are poorly absorbed in the small intestine and can ferment in the colon, leading to gas, bloating, and spasms. By eliminating these food components, many individuals experience a dramatic reduction in symptoms.

Additionally, food intolerances, such as lactose or gluten sensitivity, may be underlying contributors to gastrointestinal spasms. While not all patients with a spastic colon require extensive dietary restrictions, maintaining a symptom diary and undergoing targeted food elimination trials can help pinpoint specific aggravators. It is always recommended that such interventions be guided by a registered dietitian to avoid nutritional deficiencies.

Hormonal Influences and the Female Gut

There is a striking gender disparity in the prevalence of spastic colon and IBS, with women being disproportionately affected. Hormonal fluctuations, particularly those involving estrogen and progesterone, appear to modulate gut motility and pain sensitivity. Many women report an increase in spastic colon attacks during their menstrual cycle, particularly in the luteal phase, when progesterone levels are higher.

The precise mechanisms remain under investigation, but research suggests that estrogen can enhance the sensory thresholds in the gut, while progesterone may slow intestinal transit. This hormonal interplay may create a perfect storm for gastrointestinal spasms, particularly in women who are already predisposed due to other factors such as stress, food sensitivities, or genetic predisposition.

Hormonal treatments, including birth control pills or hormone replacement therapy, may influence symptom severity, although responses vary between individuals. Importantly, this gendered component of spastic colon syndrome calls for more personalized and sex-specific treatment strategies, acknowledging that female patients may experience symptoms in ways that differ from their male counterparts.

Differential Diagnosis and When to Seek Medical Attention

Because spastic colon attacks can mimic the symptoms of more serious conditions, a thorough differential diagnosis is essential. Symptoms such as blood in the stool, unexplained weight loss, nocturnal diarrhea, or persistent fatigue should prompt immediate medical evaluation. These signs may indicate inflammatory conditions like ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, or even colorectal malignancy.

Questions about whether conditions like IBS can cause rectal bleeding are common. Medically, the answer is nuanced. While IBS itself does not typically cause bleeding, secondary factors such as hemorrhoids or anal fissures—which may develop from chronic straining or frequent bowel movements during an IBS attack—can result in small amounts of blood in the stool. Thus, when patients ask, “Does IBS cause blood in stool?” or “Can irritable bowel cause blood in stools?”, the distinction between primary and secondary causes must be clearly explained.

More controversially, there has been inquiry into whether irritable bowel syndrome can be caused by traumatic events, including sexual trauma. While the phrase “irritable bowel syndrome caused by sodomy” is sensitive and requires cautious framing, it reflects real concerns about the psychosomatic consequences of trauma. Studies have shown that individuals with a history of abuse or trauma may experience heightened gut sensitivity and an increased risk of developing functional gastrointestinal disorders. Therefore, trauma-informed care is crucial in evaluating and managing patients with chronic gastrointestinal symptoms.

Understanding the Mechanics Behind Colon Spasms

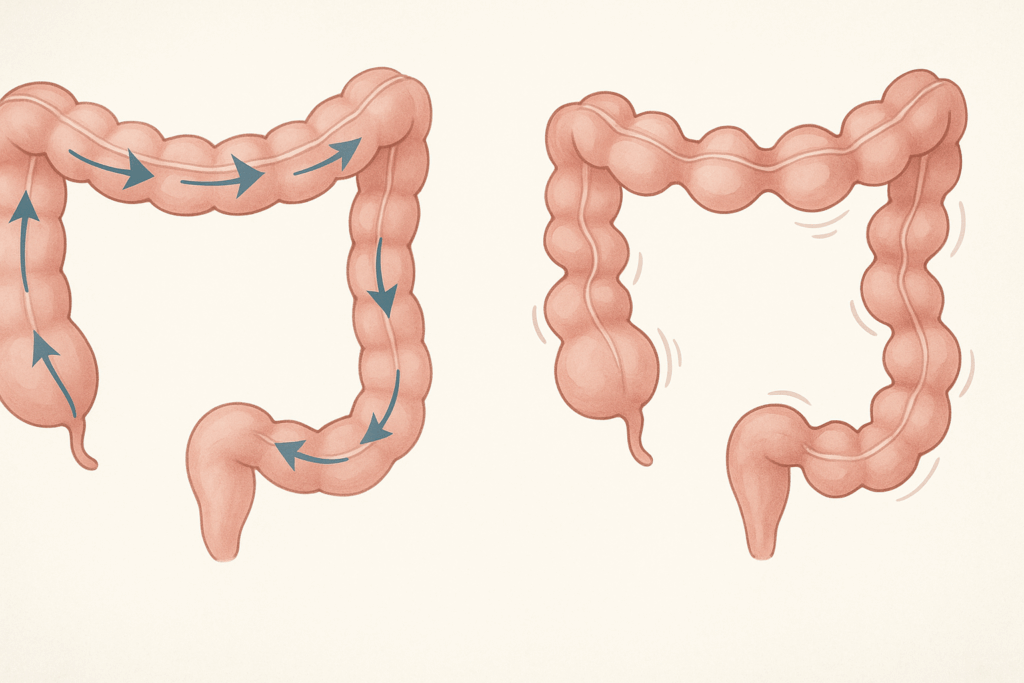

Colon spasms are the physiological signature of a spastic colon. These spasms arise from an imbalance in the autonomic regulation of intestinal smooth muscle, leading to uncoordinated contractions. The enteric nervous system, sometimes called the “second brain,” regulates this motor activity, but it can become dysregulated due to stress, inflammation, or dietary irritation.

What causes gastrointestinal spasms can vary from person to person, but the underlying issue usually involves hypersensitivity of the colon wall to normal stimuli, such as stretching or gas. This hypersensitivity, in turn, prompts exaggerated muscle contractions. These spasms may interrupt the normal migratory motor complex, a rhythmic wave of activity that sweeps through the intestines, leading to discomfort, incomplete evacuation, or urgent diarrhea.

Because the condition is functional—meaning there are no visible structural abnormalities on imaging or endoscopy—diagnosing and managing spastic colon requires a high degree of clinical intuition and patient-centered evaluation. Ruling out organic causes, such as infections, celiac disease, or malignancies, is often the first step before a diagnosis of spastic colon syndrome is confirmed.

Managing and Treating Spastic Colon Attacks

Effective treatment of spastic colon attacks involves a multifaceted approach that addresses both physiological and psychological triggers. Pharmacological therapies can include antispasmodics, such as dicyclomine or hyoscyamine, which help relax the intestinal muscles and reduce the severity of spasms. For some, low-dose antidepressants like amitriptyline can modulate pain perception and gut motility, even in the absence of depression.

Dietary interventions remain foundational. Identifying food sensitivities, avoiding high-FODMAP triggers, and maintaining a regular eating schedule can significantly reduce the frequency of colon cramps. In some cases, probiotics may help rebalance the gut microbiome, especially when symptoms are driven by post-infectious dysbiosis.

Psychological therapies also play a central role. Since stress is a well-established precipitant of spastic stomach and colon symptoms, mind-body interventions can be highly effective. These include cognitive behavioral therapy, biofeedback, and progressive muscle relaxation. When practiced regularly, these techniques can recalibrate the autonomic nervous system, reducing the likelihood of an IBS attack.

The Importance of a Personalized, Holistic Approach

No two cases of spastic colon are exactly alike, which underscores the importance of individualized care. A holistic approach that includes dietary management, stress reduction, pharmacotherapy, and psychological support offers the best chance of long-term relief. For many patients, working with a multidisciplinary team that includes gastroenterologists, dietitians, mental health professionals, and primary care providers can provide a roadmap to recovery.

Moreover, education is key. Understanding that spastic colon causes are multifactorial—spanning from neurochemical imbalances to gut flora disturbances and even trauma histories—empowers patients to become active participants in their own care. In doing so, they can better manage the unpredictability of colon spasms and reclaim their quality of life.

Frequently Asked Questions: Spastic Colon Attacks, Colon Spasms, and Digestive Distress

1. Can emotional trauma or psychological stress permanently alter colon function and lead to recurring spastic colon attacks?

Yes, significant psychological trauma can have long-lasting effects on gastrointestinal health, particularly when it involves disruptions to the autonomic nervous system. Chronic stress activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which affects gut motility, sensitivity, and immune regulation. Over time, this can lead to a condition where the colon becomes hypersensitive to stimuli, increasing the likelihood of spastic colon attacks. Recurrent psychological stress has also been linked to structural changes in the enteric nervous system, which may exacerbate colon spasms. Thus, stress management isn’t just a symptom-control strategy—it can be a foundational treatment for long-term spastic colon causes.

2. How does a spastic colon differ from other functional GI disorders like functional dyspepsia or cyclic vomiting syndrome?

Although all functional gastrointestinal disorders share the characteristic of symptom-based diagnosis without visible structural abnormalities, they differ in localization and primary symptoms. A spastic colon mainly affects the large intestine and is marked by colon cramps, irregular bowel movements, and spastic bowel patterns. In contrast, functional dyspepsia centers on upper GI symptoms like early satiety, bloating, and nausea, while cyclic vomiting syndrome is characterized by recurrent bouts of vomiting with symptom-free intervals. These conditions may overlap due to shared neurological pathways, but colon spasms symptoms are distinct in that they often involve alternating constipation and diarrhea. Understanding these differences helps target treatment more precisely and avoid misdiagnosis.

3. Can colon spasms be linked to post-infectious syndromes or changes in gut microbiota?

Yes, a growing body of research supports a strong link between post-infectious inflammation and long-term disruptions in gut motility and sensitivity, which can trigger chronic colon spasms. After an episode of gastroenteritis or food poisoning, some individuals experience persistent low-grade inflammation in the gut lining, leading to spastic colon syndrome. These post-infectious changes often coincide with alterations in gut flora, which can destabilize digestion and increase intestinal sensitivity. In such cases, colon cramps may begin weeks or even months after the initial infection has resolved. Treatments targeting microbiota balance, such as specific probiotics or dietary prebiotics, may help stabilize symptoms.

4. Is there a difference between spastic stomach and spastic colon, and can they occur simultaneously?

While both terms describe muscle spasms in different sections of the gastrointestinal tract, their causes and symptoms can overlap. A spastic stomach typically refers to upper gastrointestinal spasms affecting the stomach and duodenum, often presenting as nausea, bloating, or epigastric pain. A spastic colon, on the other hand, refers to lower GI muscle spasms, usually involving colon cramps and bowel irregularities. In some individuals, these conditions may co-occur, especially when a dysregulated autonomic nervous system or gut-brain axis is involved. Because both spastic stomach and spastic colon respond to stress, dietary irritants, and hormonal changes, they are often addressed using overlapping treatments.

5. What role does pelvic floor dysfunction play in chronic spastic bowel symptoms?

Pelvic floor dysfunction is an underrecognized contributor to spastic bowel and chronic constipation, particularly in patients who report incomplete evacuation or rectal pain. The muscles of the pelvic floor must coordinate properly to facilitate normal defecation, and disruptions in this coordination can amplify colon spasms symptoms. In cases where spastic colon attacks are frequent and unresponsive to standard treatment, a pelvic floor assessment might reveal paradoxical contraction or muscle tightness. Physical therapy targeted at pelvic floor retraining, often combined with biofeedback, can significantly reduce both colon cramps and spastic colon attacks. This multidisciplinary approach reflects the complexity of spastic colon causes.

6. Are there specific medications or supplements that may unintentionally worsen a spastic colon attack?

Yes, several over-the-counter and prescription medications can exacerbate colon spasms or trigger a spastic colon attack. These include certain laxatives, high-dose magnesium supplements, metformin, and even some SSRIs, which may alter motility patterns in sensitive individuals. Additionally, calcium channel blockers and iron supplements may slow gut motility, increasing the likelihood of constipation-dominant spastic colon syndrome. Herbal supplements like senna or cascara can cause dependency and rebound spasms when discontinued. Patients with chronic spastic bowel symptoms should always consult a healthcare provider before initiating or discontinuing medications to avoid unintended effects.

7. Can biofeedback therapy provide long-term relief for colon cramps and IBS attacks?

Biofeedback therapy has shown promise in managing functional gastrointestinal disorders by retraining the body’s autonomic responses. By monitoring physiological signals such as muscle tension and heart rate variability, patients can learn to recognize early signs of stress-induced colon spasms. With consistent practice, biofeedback can reduce the severity and frequency of both colon cramps and IBS attacks. Unlike pharmacological treatments, biofeedback has the advantage of enhancing bodily awareness and self-regulation, making it an ideal complementary therapy for spastic colon syndrome. Its long-term benefits include better control over bowel habits and reduced reliance on symptom-suppressing drugs.

8. What does emerging research say about the connection between adverse sexual experiences and irritable bowel syndrome caused by sodomy?

The connection between trauma and gastrointestinal symptoms is a sensitive yet important area of clinical research. Studies have shown that survivors of sexual trauma, including sodomy, are at increased risk for developing irritable bowel syndrome, particularly when the trauma involves the pelvic region. The concept of irritable bowel syndrome caused by sodomy reflects how trauma may disrupt not only psychological well-being but also visceral sensory pathways and muscle coordination. These disruptions can manifest as chronic spastic colon, rectal hypersensitivity, and dysregulation of bowel function. Trauma-informed care models are essential in supporting recovery while recognizing the physical and emotional implications of such experiences.

9. What innovations are emerging in the treatment of spastic colon and colon spasms?

Innovative approaches to treating colon spasms are moving beyond symptom suppression toward targeted therapies that address root causes. New research into fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) suggests that restoring gut microbial diversity may reduce spastic colon symptoms in select cases. Advances in neuromodulation, such as transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation, offer non-invasive methods to regulate gut-brain communication and decrease spastic colon attacks. Additionally, novel pharmacological agents that act on serotonin receptors in the gut show promise for regulating motility and reducing colon cramps. These emerging tools are especially useful in treatment-resistant cases of spastic bowel, offering hope for better long-term management.

10. How can individuals differentiate between benign blood in stool and more serious symptoms requiring urgent evaluation?

Not all instances of blood in the stool are cause for alarm, but distinguishing between benign and serious causes is critical. In spastic colon syndrome, minor bleeding may result from hemorrhoids or anal fissures, particularly during an IBS attack marked by frequent bowel movements. However, persistent, dark, or large volumes of blood—especially when accompanied by fatigue, weight loss, or colon cramps—warrant prompt medical evaluation. When patients ask, “Does IBS cause blood in stool?” or “Can irritable bowel cause blood in stools?”, the answer is typically no, but related complications can. Therefore, any instance of irritable bowel syndrome blood in stool should not be dismissed without professional assessment.

Reflecting on Gut Health: Why Understanding Spastic Colon Attacks Matters

At its core, the experience of a spastic colon attack is one of unpredictability, vulnerability, and often, frustration. For those living with colon spasms, the condition can interrupt daily routines, strain social relationships, and erode mental well-being. Recognizing the signs, triggers, and underlying causes of these attacks is not just about symptom management—it’s about restoring a sense of control and confidence in one’s body.

By understanding what causes gastrointestinal spasms, how stress and diet interplay with colon cramps, and what therapeutic tools are available, individuals and clinicians alike can adopt a more compassionate, effective approach to care. While spastic colon syndrome remains a functional disorder, without the overt tissue damage seen in diseases like IBD, it can nonetheless exert a profound impact on a person’s quality of life. That impact deserves to be acknowledged and addressed with both medical precision and empathetic support.

In bridging the gap between the mind and the gut, between physical symptoms and psychological states, we find not only better treatment outcomes but a deeper respect for the complexity of human health. And in doing so, we illuminate a path forward for those seeking lasting relief from the often-overlooked reality of colon spasms.

Further Reading:

Colon Spasm: Causes, Symptoms, Diet & Treatment