Few topics in medicine evoke as much confusion as the terms “senility,” “dementia,” and the increasingly outdated phrase “senile dementia.” While often used interchangeably in casual conversation, these terms represent distinct concepts within the field of cognitive health. As our global population ages, understanding what is senile dementia becomes not just a semantic concern, but a crucial component of medical literacy and eldercare awareness. In this comprehensive exploration, we unravel the historical roots, clinical distinctions, and real-world implications of senile cognitive changes, distinguishing age-related cognitive decline from broader forms of dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative conditions.

You may also like: How to Prevent Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease Naturally: Expert-Backed Strategies to Reduce Your Risk Through Lifestyle and Diet

Defining What Is Senile Dementia in a Modern Medical Context

To define senile dementia with clarity, one must first examine how the term has evolved over time. Traditionally, “senile dementia” referred to the gradual decline in cognitive function that was commonly observed in the elderly. The phrase implied a natural consequence of aging, a somewhat fatalistic acceptance that with increasing age came unavoidable mental decline. However, as the science of neurology advanced, clinicians began to challenge this presumption, recognizing that not all cognitive deterioration in later life was normal or inevitable.

In modern medicine, the phrase “senile dementia” has largely been replaced by more precise terminology such as Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, or frontotemporal dementia. Despite this, the senile dementia definition still lingers in public discourse and older medical literature. Today, when discussing what is senile dementia, experts typically refer to cognitive decline associated with aging that may or may not be pathological. Importantly, age-related memory loss can be part of a spectrum that ranges from mild cognitive impairment to full-blown dementia. Thus, understanding the nuanced senile dementia meaning requires an awareness of both normal aging processes and the red flags of neurodegeneration.

Exploring the Age of Senility and Normal Cognitive Aging

The age of senility has no fixed threshold, but the risk of cognitive impairment does increase with advancing years, particularly after the age of 65. This stage of life is marked by numerous physiological shifts, including changes in brain volume, neurotransmitter levels, and vascular integrity. However, it is critical to understand that the age of senility does not imply a universal decline in mental function. Many older adults maintain sharp cognition well into their 80s and beyond.

Normal aging may involve slower information processing, occasional forgetfulness, or difficulty multitasking, but it does not typically interfere with daily functioning. These changes are often categorized under age-associated memory impairment, a non-pathological state. In contrast, senile degeneration refers to a more marked deterioration that affects problem-solving skills, language abilities, judgment, and the capacity to perform familiar tasks. Recognizing this distinction helps professionals and caregivers differentiate between benign senility and early signs of more serious cognitive disorders.

Senility vs Dementia: Clarifying the Conceptual Divide

The confusion between senility vs dementia is common, but it can be harmful when it delays diagnosis or intervention. Senility, when used colloquially, tends to imply a vague, generalized mental decline linked to old age. It is often used to describe someone who seems forgetful or confused but without clinical evaluation. Dementia, on the other hand, is a specific clinical diagnosis characterized by measurable impairment in at least two cognitive domains, such as memory, language, attention, or executive function, sufficient to interfere with daily life.

In clinical settings, dementia is not considered a normal part of aging, even though age is the greatest risk factor. The difference between senile dementia vs dementia lies in this very misconception: while the former suggests an expected consequence of growing old, the latter implies a pathological state that warrants medical attention. Understanding senility vs dementia is therefore essential for timely diagnosis and treatment planning.

Unpacking the Senile Dementia Meaning Through a Historical Lens

To further understand the senile dementia meaning, it is useful to explore its etymology and historical usage. The word “senile” comes from the Latin “senilis,” meaning “of old age.” In the 19th and early 20th centuries, physicians used the term “senile dementia” to describe a mental decline presumed to result from old age. However, as the field of neuropsychiatry advanced, researchers began to recognize specific disease processes, such as Alzheimer’s disease, that could explain such declines.

The senile dementia definition began to shift accordingly. Alzheimer’s disease, initially considered a rare early-onset condition, was later found to account for the majority of dementia cases in older adults. This revelation contributed to a semantic shift, encouraging clinicians to abandon the nonspecific term “senile dementia” in favor of diagnoses that reflected underlying pathology. Still, in many communities and lay conversations, the term persists, underscoring the need for public education on its limitations.

Senile Dementia vs Dementia: Why the Terminology Still Matters

Although many experts consider the term “senile dementia” outdated, it still appears in older medical texts, insurance records, and patient discussions. For this reason, understanding the difference between senile dementia vs dementia remains relevant. Language shapes perception, and the continued use of outdated terminology may lead to underdiagnosis or neglect of treatable conditions.

The distinction is not merely academic. A person described as “senile” might not receive the diagnostic workup necessary to uncover reversible causes of cognitive decline, such as medication side effects, vitamin deficiencies, thyroid dysfunction, or depression. Moreover, mislabeling someone as having “senile dementia” may cause caregivers to underestimate the severity or progression of their condition. Therefore, precise language improves care outcomes and supports a more nuanced understanding of cognitive health in aging.

What Is Senility and How Is It Viewed Today?

So what is senility in contemporary clinical practice? While the word remains in popular use, it is not a formal medical diagnosis. Instead, senility often functions as a catch-all term for the forgetfulness, confusion, or personality changes observed in some older adults. However, such symptoms should always prompt further evaluation rather than being dismissed as a normal consequence of aging.

Today’s medical professionals emphasize the importance of early detection and differential diagnosis when older adults present with cognitive concerns. Memory loss could stem from a wide array of sources, including mild cognitive impairment, dementia, depression, metabolic imbalances, or even sleep disorders. Understanding what is senility involves recognizing these potential causes and not assuming that any cognitive decline in late life is inevitable or untreatable.

Understanding Senile Degeneration and Brain Changes with Age

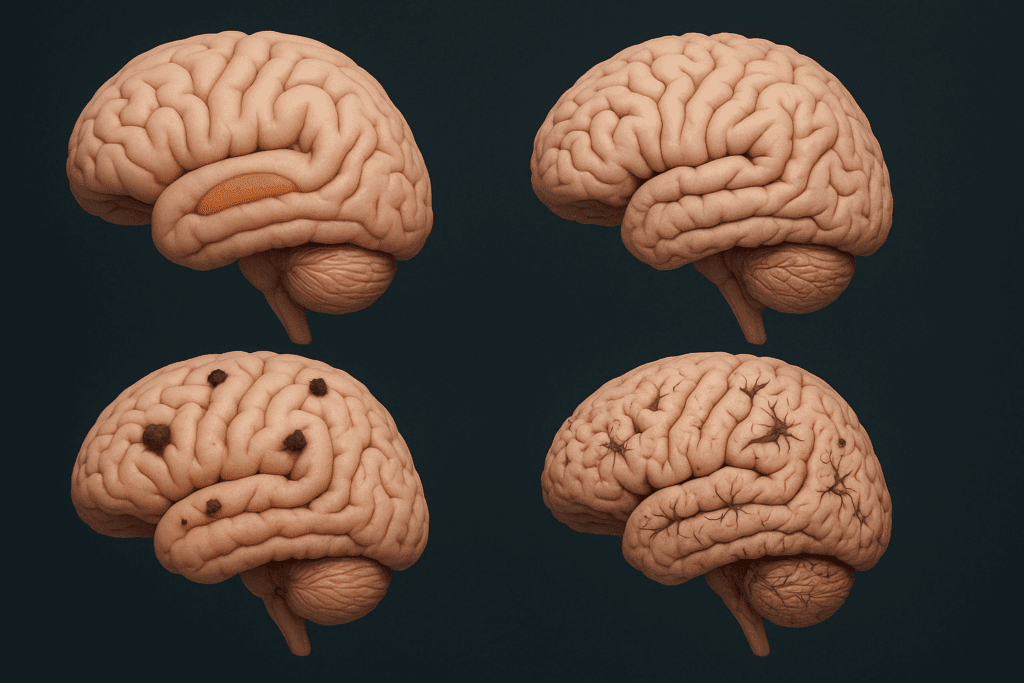

The concept of senile degeneration refers to the cumulative deterioration of tissues and organs associated with aging, including the brain. In the neurological context, this degeneration may involve loss of neurons, shrinking of brain regions such as the hippocampus, and declines in synaptic plasticity. While some degree of degeneration is a natural part of the aging process, excessive changes may signal disease.

For example, in Alzheimer’s disease, there is an abnormal buildup of beta-amyloid plaques and tau tangles that disrupt neuronal communication and lead to cell death. In vascular dementia, chronic reduced blood flow to the brain results in tissue damage. Though these processes may occur more frequently in older adults, they represent pathological aging rather than inevitable senility. Understanding senile degeneration thus involves discerning which changes are within the range of normal aging and which are signs of a neurodegenerative disorder.

Clinical Assessment and Diagnosis in the Elderly

Diagnosing cognitive decline in older adults requires a careful and comprehensive assessment. Clinicians often begin by gathering a detailed medical history, including any changes in memory, language, attention, or executive function. A neurological examination, blood tests, and brain imaging may be employed to identify underlying causes.

Standardized cognitive tests, such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) or Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), help quantify impairment and track progression over time. Importantly, a diagnosis of dementia requires that cognitive deficits significantly interfere with independence and daily activities. Distinguishing between what is senile dementia and more specific diagnoses helps guide treatment options and care planning.

Treatment Approaches and Interventions for Age-Related Cognitive Decline

Treatment for cognitive decline in older adults depends on the underlying cause. If the decline is due to a reversible condition, such as a medication side effect or nutritional deficiency, addressing the root issue can result in significant improvement. In cases of progressive dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease, treatments may focus on slowing the progression and improving quality of life.

Pharmacological interventions, such as cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine, are sometimes used to manage symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Non-pharmacological interventions, including cognitive training, physical exercise, and social engagement, also play an essential role. Education for caregivers and structured routines can support daily function. Recognizing the senile dementia meaning within this broader context helps ensure that interventions are individualized and comprehensive.

The Emotional and Social Dimensions of Senility

Beyond clinical symptoms, the emotional and social consequences of senility can be profound. Older adults experiencing cognitive decline may feel isolated, frustrated, or anxious. Misunderstandings about what is senility may lead family members to dismiss or minimize their concerns. Stigma surrounding cognitive impairment may prevent individuals from seeking help until symptoms become severe.

Addressing these psychosocial dimensions is a vital component of dementia care. Support groups, counseling, and open communication can reduce stigma and enhance well-being. Recognizing that age-related cognitive decline does not diminish a person’s dignity or worth fosters a more compassionate and effective approach to care. The language we use—whether referring to senile dementia vs dementia, or senility vs aging—shapes how individuals experience their later years.

Differentiating Between Senile Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease

It is essential to clarify the distinction between senile dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, as these terms are often mistakenly used interchangeably. Alzheimer’s disease is a specific neurodegenerative condition that accounts for 60-80% of dementia cases. It is characterized by progressive memory loss, disorientation, and ultimately, severe cognitive impairment. The pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s include beta-amyloid plaques, tau tangles, and neuronal atrophy.

In contrast, the term senile dementia may refer to a broader, less specific set of cognitive symptoms occurring in older age. While Alzheimer’s disease may present during the age of senility, the two are not synonymous. Clarifying this distinction aids in accurate diagnosis and tailored care. It also underscores the importance of updating public and clinical language to reflect contemporary understanding.

Prevention and Lifestyle Factors: Can Senile Dementia Be Delayed?

While aging is inevitable, cognitive decline is not always predetermined. Emerging research suggests that certain lifestyle factors can delay or reduce the risk of age-related cognitive decline. Regular physical activity, intellectual engagement, a heart-healthy diet, and strong social connections have all been associated with better brain aging outcomes.

Addressing cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and smoking is particularly important, as these can contribute to vascular changes that exacerbate cognitive decline. Early intervention for depression, sleep disorders, and sensory impairments may also reduce the burden of cognitive symptoms. Understanding what is senile dementia in this context allows for a proactive approach to mental aging, emphasizing resilience and brain health.

Why Public Understanding of the Senile Dementia Definition Matters

Public health initiatives increasingly recognize the need for accurate, accessible information about aging and cognition. Misconceptions about what is senility or the senile dementia definition can lead to neglect, delay in care, and increased caregiver burden. When families understand the signs of pathological cognitive decline, they are more likely to seek timely medical evaluation and support.

Educational campaigns aimed at demystifying terms like senile dementia vs dementia can empower older adults and their caregivers to advocate for appropriate care. Such efforts also help dismantle stigma, encouraging open conversations about memory, mental health, and the aging process. Ultimately, precision in language reflects respect for the lived experiences of older adults and advances in clinical understanding.

Conclusion: Understanding Senile Dementia to Improve Aging and Care

Grasping the full scope of what is senile dementia requires more than a dictionary definition. It demands an appreciation for the historical, clinical, emotional, and social contexts in which this term has evolved. As our population ages and cognitive disorders become more prevalent, distinguishing between normal aging, senility, and pathological dementia becomes increasingly vital.

Understanding senility vs dementia is not just a semantic exercise but a crucial step in promoting timely diagnosis, appropriate care, and compassionate support. The continued use of the term “senile dementia” may obscure more precise diagnoses, delaying interventions that could improve quality of life. Therefore, transitioning toward terminology that reflects contemporary science not only enhances medical accuracy but also honors the dignity of older adults.

By exploring the meaning of senile degeneration, the age of senility, and the true senile dementia definition, we open the door to a more informed, empathetic, and proactive approach to aging. Whether you are a healthcare provider, a caregiver, or an aging adult yourself, understanding the difference between senile dementia vs dementia empowers you to navigate the challenges of cognitive aging with clarity and confidence. Through education, awareness, and evidence-based care, we can replace outdated assumptions with informed action—and in doing so, promote healthier, more fulfilling lives in our later years.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out.

Further Reading:

Distinguishing Alzheimer’s disease from other major forms of dementia

How Senility and Dementia Differ

Disclaimer

The information contained in this article is provided for general informational purposes only and is not intended to serve as medical, legal, or professional advice. While Health11News strives to present accurate, up-to-date, and reliable content, no warranty or guarantee, expressed or implied, is made regarding the completeness, accuracy, or adequacy of the information provided. Readers are strongly advised to seek the guidance of a qualified healthcare provider or other relevant professionals before acting on any information contained in this article. Health11News, its authors, editors, and contributors expressly disclaim any liability for any damages, losses, or consequences arising directly or indirectly from the use, interpretation, or reliance on any information presented herein. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of Health11News.