Introduction: Why Understanding the Cerebrum Matters for Mental and Cognitive Health

The cerebrum, the largest and most complex part of the human brain, is fundamental to our identity, behavior, and cognitive capabilities. It governs thought, memory, emotion, language, and voluntary movement. Despite its significance, the cerebrum remains a mystery to many outside the neuroscience and mental health fields. For those seeking to optimize mental well-being and cognitive performance, understanding how this structure functions is not merely academic—it is deeply practical. At the core of its structure are four distinct lobes, each responsible for a different set of functions, with the frontal and temporal lobes playing especially vital roles in emotional regulation, problem-solving, and memory.

Understanding the cerebrum requires an appreciation of its anatomical intricacies and the dynamic relationships between its parts. Questions like “how many lobes are in the cerebrum?” may appear basic, but they open the door to deeper insights into how brain structures support or impair our mental wellness. Moreover, the frontal temporal parts of the brain are uniquely sensitive to aging, trauma, and disease, making them especially important in clinical and preventative mental health settings. This article will provide an in-depth, medically accurate, and SEO-optimized exploration of the cerebrum, with a particular focus on the cerebrum temporal lobe and frontal lobe functions. By doing so, it aims to empower readers with a foundational yet sophisticated understanding of how these brain structures influence both our everyday experiences and long-term health trajectories.

You may also like: Boost Brain Power Naturally: Evidence-Based Cognitive Training Activities and Memory Exercises That Support Long-Term Mental Health

Anatomy of the Cerebrum: How Many Lobes Are in the Cerebrum and What Do They Do?

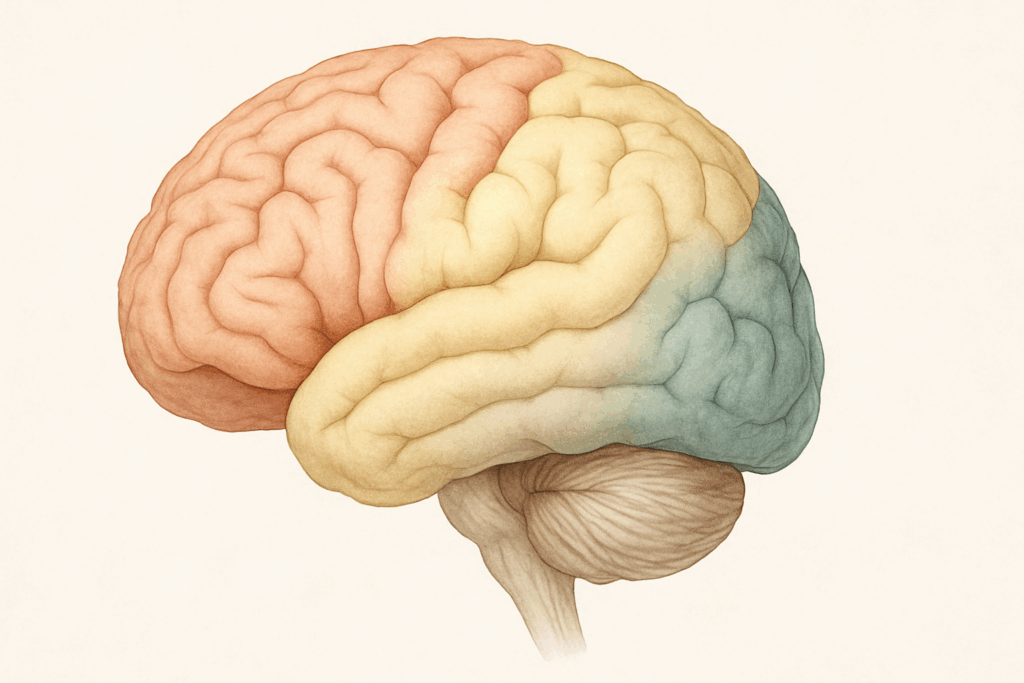

To begin any meaningful discussion about the cerebrum, it is important to address the question: how many lobes are in the cerebrum? The answer is four—frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital. Each lobe is associated with distinct sets of functions, but they operate in concert through highly interconnected neural pathways. This structural division allows for specialized processing while maintaining the integration necessary for coherent perception, action, and emotion.

The frontal lobe sits at the front of the brain and is often described as the control panel for our personality and decision-making. It is responsible for executive functions such as reasoning, planning, and impulse control. The cerebrum temporal lobe, located on the sides of the brain near the temples, is central to auditory processing, language comprehension, and memory storage. The parietal lobe, situated above the temporal lobe and behind the frontal lobe, integrates sensory information related to touch, temperature, and spatial awareness. Lastly, the occipital lobe, found at the back of the brain, is dedicated to visual processing.

Though the question of how many lobes are in the cerebrum can be answered in one sentence, the implications of these lobes’ functions are vast and deeply intertwined with our understanding of mental health. Disorders such as schizophrenia, depression, and dementia have all been linked to dysfunction in one or more of these lobes. Thus, knowing the lobes is not just about memorizing anatomy—it is about appreciating how damage or disruption in one region can ripple across the entire system, manifesting in complex behavioral and emotional symptoms.

The Frontal Lobe: Executive Function, Emotional Control, and Mental Health

The frontal lobe is perhaps the most evolutionarily advanced part of the cerebrum and plays a defining role in what makes us human. It houses the prefrontal cortex, which is involved in goal-setting, decision-making, and social behavior. It also includes the motor cortex, responsible for voluntary movement. Crucially, the frontal lobe helps regulate emotions, especially those related to social interaction and moral reasoning. This makes it foundational to both mental stability and adaptability.

The frontal temporal parts of the brain, particularly within the prefrontal cortex, are known for their role in impulse control and delayed gratification. These functions are highly relevant in conditions like ADHD, bipolar disorder, and borderline personality disorder, where frontal lobe dysfunction is frequently observed. Moreover, damage to this region due to traumatic brain injury, stroke, or degenerative diseases can result in profound changes in personality, judgment, and behavior.

From a therapeutic perspective, interventions that strengthen frontal lobe function—such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, mindfulness training, and neurofeedback—are commonly used to improve emotional regulation and executive functioning. This further emphasizes the centrality of this region in mental health. Understanding the frontal lobe’s role allows clinicians to better diagnose disorders and tailor interventions that promote cognitive resilience and emotional balance.

The Cerebrum Temporal Lobe: Memory, Language, and Emotional Perception

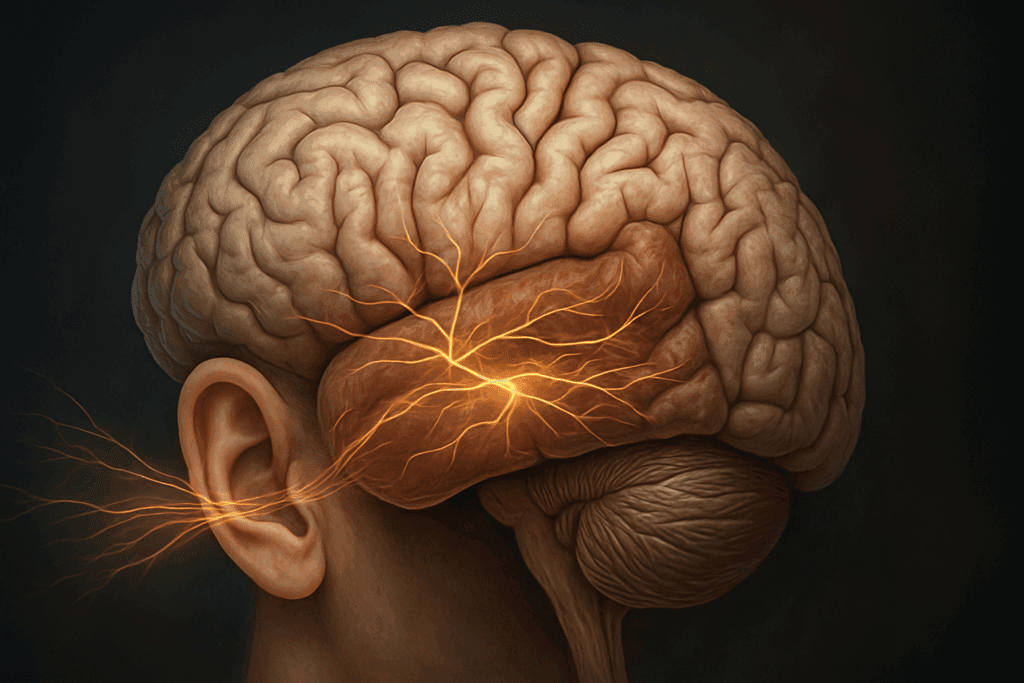

The cerebrum temporal lobe is another powerhouse of cognitive and emotional processing. Nestled beneath the lateral fissure and close to the ears, it is heavily involved in processing auditory stimuli, language, and memory formation. The hippocampus, a structure critical for converting short-term memories into long-term ones, is located within this lobe. It is also where the amygdala resides, a key player in the regulation of emotions such as fear and pleasure.

Dysfunction in the cerebrum temporal lobe has been linked to a range of psychiatric and neurological conditions, including Alzheimer’s disease, temporal lobe epilepsy, and schizophrenia. Individuals with damage in this region may experience hallucinations, memory loss, or language impairments such as aphasia. The richness and diversity of symptoms stemming from temporal lobe dysfunction underscore its importance in clinical practice.

What makes the cerebrum temporal lobe particularly fascinating is its involvement in both rational and emotional aspects of experience. While it processes words and sounds with analytical precision, it also imbues those experiences with emotional significance. This dual capacity makes it integral to how we form attachments, interpret social cues, and recall meaningful events. Therapeutic interventions for trauma and PTSD often target memory circuits housed within this lobe, demonstrating how deeply it influences both conscious thought and subconscious processing.

Interconnectivity: How the Frontal Temporal Parts of the Brain Work Together

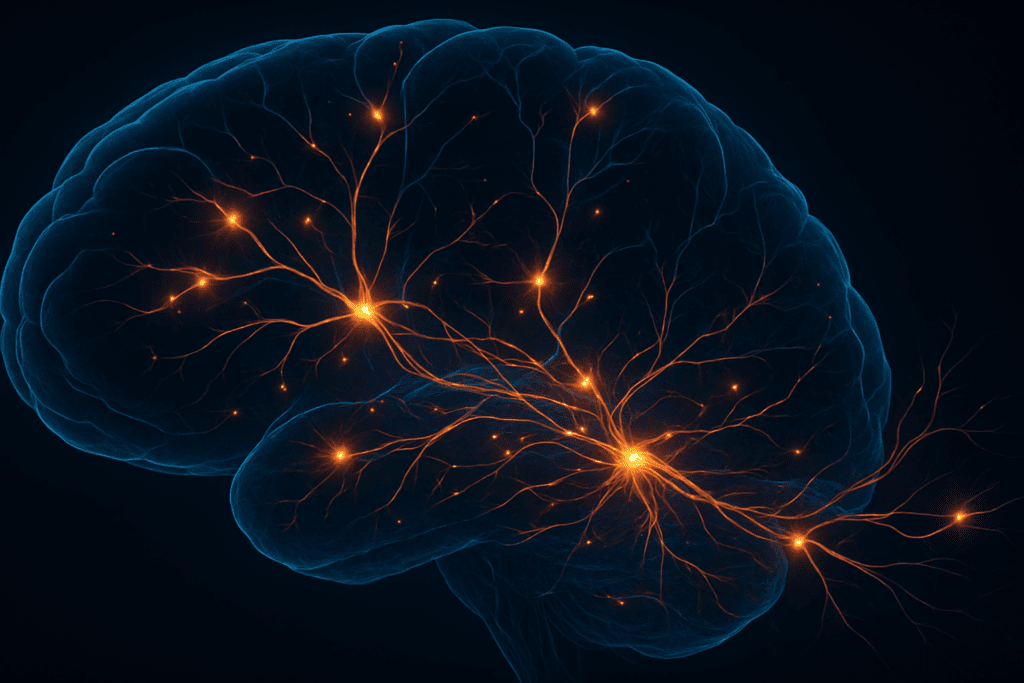

While each lobe of the cerebrum serves specialized functions, it is the seamless interaction between them that gives rise to integrated consciousness and behavior. The frontal temporal parts of the brain, in particular, form a dense web of neural connections that support speech, social cognition, memory, and decision-making. The uncinate fasciculus, a white matter tract, connects parts of the frontal lobe with the anterior temporal lobe, enabling rapid communication between emotional and executive centers.

This interconnectivity is critical in complex cognitive processes such as empathy, theory of mind, and moral reasoning. For instance, when you hear a loved one’s voice (a task involving the cerebrum temporal lobe), and then decide how to respond with sensitivity and care (a function of the frontal lobe), multiple brain regions are working in concert. When these connections break down, as in frontotemporal dementia or severe traumatic brain injury, the result is often a profound deterioration in social and emotional intelligence.

Modern imaging technologies like fMRI and DTI (diffusion tensor imaging) have shed light on these networks, enabling clinicians and researchers to observe how the frontal temporal parts of the brain co-activate during tasks. These insights not only improve diagnostic accuracy but also help guide rehabilitation strategies that aim to restore or compensate for impaired pathways. Ultimately, understanding the dynamics of these regions helps us appreciate that mental health is not the product of isolated brain structures, but of the rich and reciprocal interactions between them.

Developmental Perspectives: How the Cerebrum Shapes Cognitive Growth Across the Lifespan

Brain development is not a static process, and the cerebrum reflects this beautifully. From infancy through old age, the cerebrum undergoes structural and functional changes that influence how we think, feel, and behave. During childhood, the frontal lobe is still maturing, which explains why young children often struggle with impulse control and long-term planning. Adolescence is marked by rapid synaptic pruning and myelination, particularly in the frontal temporal parts of the brain, which enhances cognitive efficiency but also introduces vulnerabilities to psychiatric disorders.

In adulthood, the cerebrum stabilizes to some extent, supporting peak performance in reasoning, memory, and social functioning. However, even in this stage, neuroplasticity allows for continued growth and adaptation. This is particularly encouraging for those engaged in lifelong learning or cognitive rehabilitation. As we age, the cerebrum becomes more susceptible to shrinkage, particularly in the frontal and temporal lobes. This age-related atrophy is associated with declines in memory, processing speed, and emotional regulation.

Understanding how many lobes are in the cerebrum and how each contributes to development helps inform early interventions and preventative strategies. For example, language enrichment in early childhood can promote temporal lobe development, while mindfulness and aerobic exercise in older adults have been shown to preserve frontal lobe volume. Thus, knowledge of cerebral development is essential not only for understanding disease but also for optimizing cognitive and emotional wellness across the lifespan.

Neurological Disorders Involving the Frontal and Temporal Lobes

Disorders involving the frontal temporal parts of the brain can have profound effects on personality, behavior, and cognition. Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is a stark example. Unlike Alzheimer’s disease, which primarily affects memory, FTD tends to alter judgment, social behavior, and language first. Patients may become disinhibited, apathetic, or emotionally indifferent, reflecting damage to both frontal and temporal structures.

Similarly, epilepsy localized in the cerebrum temporal lobe often presents with auras, déjà vu, and emotional disturbances. This form of epilepsy is notoriously difficult to manage with medication and sometimes requires surgical intervention. Psychiatric conditions like schizophrenia also frequently involve abnormalities in the frontal and temporal lobes, as evidenced by imaging studies showing reduced volume and disrupted connectivity.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is another condition that disproportionately affects the frontal lobe, particularly in sports-related and military contexts. Even mild TBIs can impair executive function and emotional regulation, with long-term implications for mental health. Understanding these disorders not only highlights the importance of early detection and targeted therapy but also reinforces the need for continued research into the roles of the cerebrum’s lobes in maintaining mental stability.

Enhancing Brain Health: Strategies to Support the Cerebrum’s Lobes

Optimizing the health of the cerebrum’s lobes, particularly the frontal and temporal regions, requires a multidimensional approach. Lifestyle factors such as regular physical activity, adequate sleep, and a balanced diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids are foundational. These habits enhance neuroplasticity and reduce inflammation, supporting cognitive resilience. Cognitive training, including memory exercises and problem-solving tasks, can also stimulate frontal and temporal regions, preserving function with age.

Mindfulness practices and stress reduction techniques are particularly effective in strengthening the frontal temporal parts of the brain. Studies using brain imaging have shown increased gray matter density in these areas among long-term meditators. Social engagement, too, plays a key role in maintaining temporal lobe health, as meaningful conversations and emotional connections activate the very circuits that are vulnerable to degeneration.

Technological interventions such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and neurofeedback are also showing promise in clinical contexts. These methods aim to directly modulate activity in specific brain regions, offering hope for those with treatment-resistant conditions. Ultimately, supporting the cerebrum is not about isolated fixes but about creating an environment—physiological, psychological, and social—that nurtures its intricate networks.

Frequently Asked Questions: Understanding the Cerebrum and Its Impact on Mental Health

1. How do lifestyle choices specifically influence the frontal temporal parts of the brain?

Lifestyle factors such as sleep, stress management, nutrition, and physical activity play an essential role in maintaining the integrity of the frontal temporal parts of the brain. Chronic sleep deprivation, for example, has been shown to reduce gray matter volume in the prefrontal cortex and disrupt communication with the cerebrum temporal lobe. These changes impair executive functioning, decision-making, and emotional regulation. Conversely, regular physical exercise promotes neurogenesis and strengthens neural connectivity, especially between the frontal and temporal lobes. Engaging in mentally stimulating activities, such as learning new languages or playing musical instruments, also helps reinforce the frontal temporal network, promoting resilience against age-related cognitive decline. Nutritional choices, including diets rich in omega-3 fatty acids, antioxidants, and B-complex vitamins, have demonstrated neuroprotective effects that support long-term brain health. These interventions enhance synaptic plasticity and delay neurodegenerative processes that often target the frontal temporal parts of the brain.

2. Can targeted cognitive training improve function in the cerebrum temporal lobe?

Yes, targeted cognitive training programs can enhance specific functions governed by the cerebrum temporal lobe. For example, memory-based exercises, language comprehension tasks, and auditory processing games are designed to stimulate this region. Research shows that consistent training in these areas can lead to functional reorganization within the cerebrum temporal lobe, even in older adults or those recovering from neurological injury. Additionally, combining cognitive exercises with transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) may amplify these gains by increasing cortical excitability in the targeted lobe. Importantly, these programs must be personalized and progressively challenging to maintain engagement and neuroplasticity. While such training does not cure neurodegenerative diseases, it can significantly delay symptom progression and improve quality of life. These outcomes underscore the value of early, proactive strategies to preserve the cerebrum temporal lobe’s capacity.

3. What are some early signs of dysfunction in the frontal temporal parts of the brain that often go unnoticed?

Subtle changes in social behavior, emotional expression, and impulse control are often early indicators of dysfunction in the frontal temporal parts of the brain. These signs can precede more severe cognitive impairments by years. For instance, a person might begin exhibiting unusually inappropriate humor, reduced empathy, or increased impulsivity—behaviors that may be mistakenly attributed to stress or personality changes. In some cases, individuals may lose the ability to interpret social cues, leading to interpersonal difficulties. Unlike more dramatic symptoms such as memory loss or language deficits, these early signs of dysfunction in the frontal temporal parts of the brain are easy to overlook. Clinical neuropsychological assessments can help detect these subtle patterns before they evolve into more serious conditions, such as frontotemporal dementia. Monitoring behavioral shifts in high-risk individuals, particularly those with a family history of neurodegenerative disease, is critical for early intervention.

4. How does the structure of the cerebrum allow it to balance specialization with integration across all four lobes?

The structural organization of the cerebrum elegantly balances functional specialization and inter-lobar communication. When considering how many lobes are in the cerebrum, the answer—four—belies a much more complex interplay. Each lobe—frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital—has its own specialized processing centers, but white matter tracts such as the arcuate fasciculus, corpus callosum, and uncinate fasciculus ensure ongoing integration. For instance, the frontal lobe’s executive functions are deeply reliant on temporal lobe inputs for context and memory. This dynamic interdependence is particularly evident in language processing, where Broca’s area (frontal) and Wernicke’s area (temporal) must synchronize efficiently. Moreover, brain imaging reveals that cognitive tasks as diverse as reading, emotional appraisal, and navigation involve coordinated activation across multiple lobes. The cerebrum’s architecture is thus designed to foster both modularity and unity, ensuring robust mental performance under various demands.

5. Are the frontal temporal parts of the brain more vulnerable to trauma than other regions?

The frontal temporal parts of the brain are indeed more susceptible to trauma, particularly in cases of closed-head injury or concussions. Their location near the bony ridges of the skull makes them prone to contusions during rapid acceleration-deceleration events, such as in car accidents or contact sports. Damage to the frontal lobe often results in changes in judgment, personality, and emotional regulation, while injuries to the cerebrum temporal lobe can impair memory and language comprehension. What makes these injuries especially challenging is that they may not immediately show up on standard imaging scans, delaying diagnosis and treatment. Even so-called mild traumatic brain injuries can lead to long-term alterations in the frontal temporal circuitry, affecting behavior and cognition for years. Understanding this vulnerability underscores the importance of preventive measures such as helmet use, sideline concussion protocols, and post-injury cognitive rehabilitation to support recovery and reduce the risk of chronic impairment.

6. How do emotional memories stored in the cerebrum temporal lobe shape long-term mental health?

Emotional memories encoded in the cerebrum temporal lobe—particularly through the amygdala and hippocampus—play a critical role in shaping long-term mental health. Traumatic events can leave a lasting imprint on these structures, influencing mood, behavior, and stress reactivity well into adulthood. For example, unresolved childhood trauma stored in the cerebrum temporal lobe can contribute to adult manifestations of anxiety, depression, or PTSD. These memories are often emotionally charged and may be reactivated by sensory cues, even in the absence of conscious recollection. On the flip side, positive emotional memories reinforce adaptive behaviors, build psychological resilience, and enhance emotional regulation. Modern therapeutic techniques like EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) directly target memory processing in the cerebrum temporal lobe to reduce the emotional intensity of traumatic recollections. Understanding the role of this lobe in memory and emotion helps therapists tailor more effective, brain-based interventions for long-term mental well-being.

7. In what ways do age-related changes in the cerebrum affect the integration between frontal and temporal lobes?

As we age, structural and functional changes in the cerebrum often disrupt the intricate balance between the frontal and temporal lobes. While most people are aware of age-related memory decline, they may not realize that the disconnection between these lobes is a key contributor. Shrinkage in the cerebrum temporal lobe can lead to poorer encoding and retrieval of new information, while frontal lobe atrophy affects executive control over attention and planning. Additionally, age-related reductions in white matter integrity—particularly in tracts linking the frontal temporal parts of the brain—further compromise this integration. These changes can manifest as difficulty following conversations, reduced multitasking ability, or increased emotional reactivity. Interventions like aerobic exercise, mental stimulation, and dietary changes aimed at preserving white matter and synaptic health may mitigate some of these age-related effects and help maintain functional connectivity between the lobes.

8. Are there sex-based differences in how the cerebrum temporal lobe functions in emotional processing?

Emerging research suggests that there are sex-based differences in the way the cerebrum temporal lobe processes emotional information. For instance, neuroimaging studies show that females tend to exhibit stronger connectivity between the cerebrum temporal lobe and limbic regions like the amygdala during emotional tasks. This may explain higher rates of affective empathy and emotional memory recall observed in women. Males, on the other hand, may show greater activation in the frontal lobe when modulating emotional responses, relying more heavily on cognitive control mechanisms. Hormonal influences, particularly estrogen and testosterone, appear to modulate these differences in brain function and structure. These findings have clinical implications, especially in understanding how different genders respond to stress, therapy, or medication. Tailoring interventions to account for such neurobiological differences may improve outcomes in mental health treatment, especially when the frontal temporal parts of the brain are targeted.

9. What role does the cerebrum play in creativity and abstract thinking?

Creativity and abstract thinking emerge from a synergy of activity across multiple cerebrum lobes, especially the frontal and temporal regions. The frontal lobe contributes to idea generation, inhibition of conventional responses, and the strategic organization of novel concepts. Meanwhile, the cerebrum temporal lobe provides semantic knowledge, emotional tone, and associative memory—key components of creative insight. This interaction is particularly visible in artists, writers, and musicians who often demonstrate heightened functional connectivity between the frontal and temporal cortices. Moreover, states of “creative flow” are associated with decreased activity in the brain’s default mode network, allowing for a temporary reorganization of frontal temporal pathways. Understanding how many lobes are in the cerebrum may seem unrelated to creativity at first, but it highlights how distinct cognitive modules collaborate to produce original thought. Enhancing this collaboration through mindfulness, improvisation exercises, or exposure to diverse stimuli can nurture creativity at any age.

10. Could advancements in neurotechnology improve diagnosis and treatment of disorders affecting the frontal temporal parts of the brain?

Yes, neurotechnology is rapidly advancing our ability to diagnose and treat conditions involving the frontal temporal parts of the brain. Tools like high-resolution functional MRI (fMRI) and magnetoencephalography (MEG) offer real-time insights into brain activity and connectivity, helping clinicians identify early signs of dysfunction. Machine learning algorithms are increasingly being used to detect subtle patterns in imaging data that may elude the human eye, improving diagnostic accuracy for conditions such as frontotemporal dementia or temporal lobe epilepsy. Furthermore, neurostimulation techniques like deep brain stimulation (DBS) and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) are being refined to target specific nodes within the frontal temporal network, offering new avenues for treatment-resistant depression or compulsive disorders. These interventions aim not only to modulate symptomatic circuits but also to restore the functional integration between key brain regions. As our understanding of how many lobes are in the cerebrum evolves into a deeper appreciation of their interactive roles, neurotechnology stands poised to usher in a new era of personalized brain health care.

Conclusion: Integrating Knowledge of the Cerebrum’s Lobes into Long-Term Mental and Cognitive Health

Understanding the cerebrum and its four lobes—particularly the frontal and temporal regions—is not merely an academic exercise but a cornerstone of lifelong mental wellness. From answering basic questions like “how many lobes are in the cerebrum” to exploring the nuanced interplay between the cerebrum temporal lobe and frontal structures, we uncover insights that resonate far beyond the clinic. The frontal temporal parts of the brain are where thought meets emotion, where decision-making intertwines with memory, and where social behavior takes shape.

Recognizing the vital roles of these regions allows us to appreciate how their dysfunction can lead to a wide array of cognitive and emotional challenges. Yet it also empowers us to take proactive steps in preserving and enhancing brain function. Whether through lifestyle changes, therapeutic interventions, or ongoing education, nurturing the health of the cerebrum is essential for maintaining emotional equilibrium, cognitive clarity, and overall well-being.

As research continues to evolve, so too will our understanding of how to support these intricate brain systems. But one truth remains clear: by valuing the complex roles of the cerebrum temporal lobe and its frontal counterpart, we move closer to a future where mental health is not only protected but optimized. In that pursuit, the science of brain anatomy becomes not just informative, but profoundly transformative.