Cognitive functioning serves as the bedrock of our ability to navigate daily life, enabling memory, language, reasoning, judgment, and executive decision-making. When these faculties decline, the impact on an individual’s autonomy and quality of life can be profound. Among the spectrum of cognitive disorders, severe cognitive impairment represents one of the most debilitating and complex forms. It is not merely forgetfulness or confusion; it is a life-altering condition that fundamentally disrupts a person’s capacity to think, remember, and interact with the world. This article aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of severe cognitive impairment—what it entails, its underlying causes, and the real-world clinical cases that help us grasp the depth and diversity of its manifestations. Drawing from medical practice and research, this discussion is grounded in both expert knowledge and lived experience, offering insights not just into the condition itself but into the lives it touches.

You may also like: How to Prevent Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease Naturally: Expert-Backed Strategies to Reduce Your Risk Through Lifestyle and Diet

Defining Severe Cognitive Impairment and Its Clinical Criteria

Severe cognitive impairment refers to a profound and often irreversible decline in mental functions that significantly interferes with a person’s ability to perform essential activities of daily living (ADLs). These may include tasks such as preparing meals, managing medications, dressing, bathing, and handling finances. Unlike mild cognitive impairment (MCI), where the individual can often function independently with some memory lapses or attention deficits, severe cognitive impairment typically signals advanced neurological dysfunction. It may arise as a result of neurodegenerative disease, severe brain injury, or an advanced stage of dementia, most commonly Alzheimer’s disease.

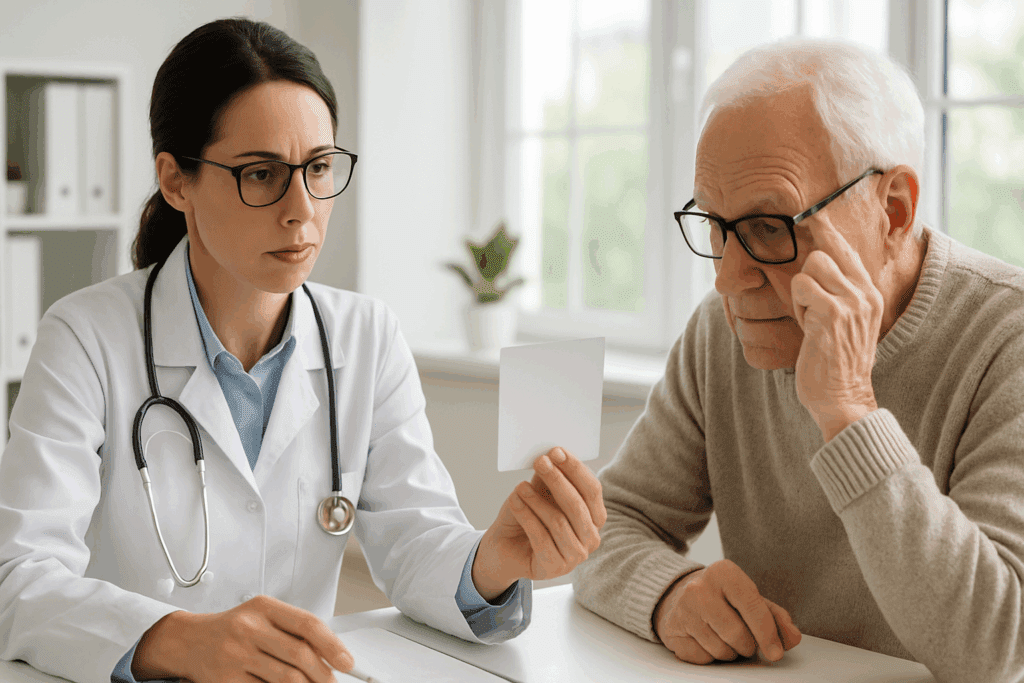

Clinically, diagnosing severe cognitive impairment involves a multidimensional assessment. Neuropsychological evaluations measure various cognitive domains including memory, attention, language, visuospatial ability, and executive function. Physicians also assess whether impairments interfere with daily functioning. In some cases, severe impairment may present with a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of less than 10, indicating marked deficits across multiple cognitive areas. However, formal testing is only part of the equation; behavioral observation and caregiver input often provide critical context for evaluating the depth and breadth of impairment.

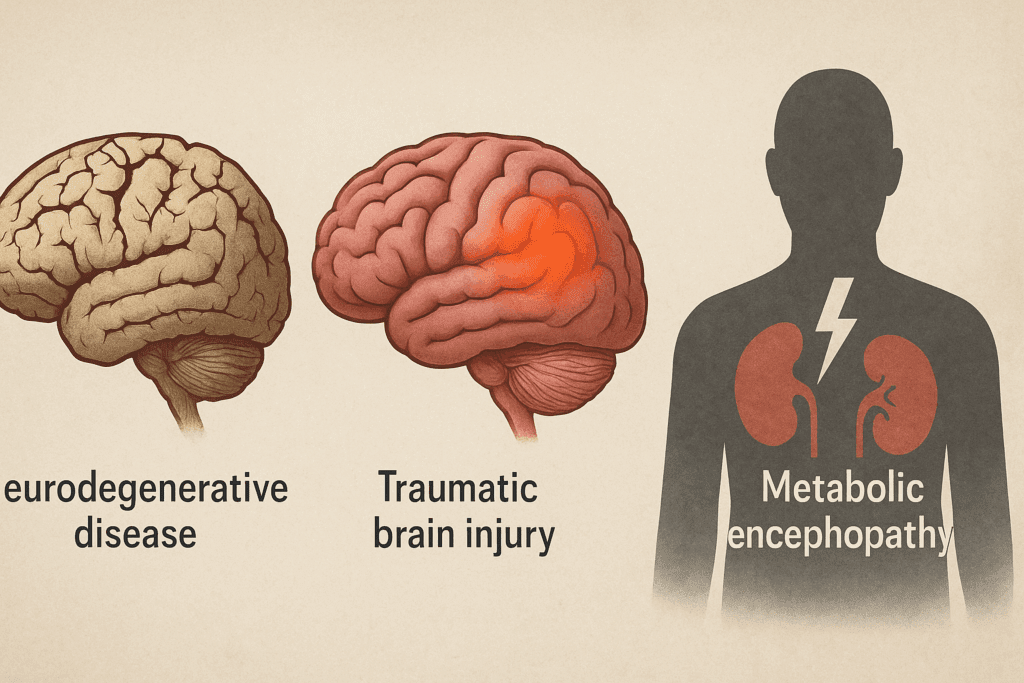

Importantly, severe cognitive impairment is not a diagnosis in itself but rather a descriptor of functional status. It is frequently a feature of established neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, Parkinson’s disease dementia, or traumatic brain injury. Each of these conditions may present with distinct cognitive profiles, but when symptoms escalate to a level where basic daily activities can no longer be performed without substantial assistance, the classification shifts into the realm of severe cognitive impairment.

The Neurological Underpinnings of Cognitive Decline

To fully understand severe cognitive impairment, one must delve into the neurological roots of how such dysfunction emerges. The brain’s intricate architecture—comprising billions of neurons and trillions of synaptic connections—relies on precise signaling to facilitate cognition. Damage to specific regions of the brain, particularly the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and parietal lobes, can lead to impairments in memory, problem-solving, spatial reasoning, and self-regulation.

Neurodegeneration, particularly in conditions like Alzheimer’s disease, is among the most well-known causes. In Alzheimer’s, the buildup of beta-amyloid plaques and tau protein tangles disrupts neuronal communication and eventually causes neuronal death. As the disease progresses, this widespread neural destruction leads to severe cognitive impairment. In vascular dementia, on the other hand, small strokes or chronic ischemia limit blood flow to the brain, producing stepwise declines in cognition and executive functioning. The resulting damage is often diffuse and can vary based on the vascular territory affected.

Other neurological disorders such as Lewy body dementia or Huntington’s disease may also progress toward severe impairment, albeit through different pathological mechanisms. Lewy bodies—abnormal protein aggregates—impair neuronal function in both cortical and subcortical regions, often producing vivid hallucinations and severe attention deficits. In all these cases, the shift to severe cognitive impairment marks a critical threshold where neuronal damage becomes extensive and the cognitive decline, unrelenting.

Common and Uncommon Causes of Severe Cognitive Impairment

While neurodegenerative disease remains the leading cause, there are numerous other pathways through which severe cognitive impairment can emerge. Traumatic brain injury (TBI), especially when involving diffuse axonal injury or frontal lobe damage, can result in profound impairments in memory, reasoning, and social behavior. In such cases, the severity of cognitive impairment may depend on the extent and location of the trauma, as well as the timing and quality of medical intervention.

Metabolic encephalopathy represents another important but often reversible cause of severe cognitive decline. Conditions such as hepatic encephalopathy, uremia, and electrolyte imbalances can significantly alter brain function, especially in older adults. In these cases, addressing the underlying metabolic derangement may lead to partial or even complete recovery of cognitive ability, underscoring the importance of accurate diagnosis.

Infectious diseases like HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder or late-stage syphilis can also lead to severe cognitive impairment. Though less common in developed nations due to widespread screening and treatment, these conditions remain a concern in certain populations and serve as reminders that cognitive health is inextricably linked to broader systemic health. In rare cases, autoimmune encephalitis and paraneoplastic syndromes may cause sudden and profound cognitive disruptions, often accompanied by psychiatric symptoms such as hallucinations, paranoia, or catatonia.

One must also acknowledge the role of substance use, particularly long-term alcohol abuse leading to Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome—a condition marked by profound memory deficits and confabulation. Unlike Alzheimer’s disease, which unfolds gradually, Wernicke-Korsakoff can present more acutely and may be at least partially responsive to treatment with thiamine supplementation. In clinical practice, identifying the exact etiology is vital, as some causes of severe cognitive impairment are reversible or modifiable if caught early.

Severe Cognitive Impairment in Real-World Medical Practice

Understanding the lived reality of severe cognitive impairment requires looking beyond test scores and diagnostic categories to the daily experiences of individuals and families affected by this condition. In clinical settings, healthcare providers often encounter patients whose cognitive decline has gone unnoticed until a crisis arises—an elderly person found wandering, a diabetic patient hospitalized due to forgotten insulin doses, or a loved one who no longer recognizes close family members.

One poignant example is that of a 72-year-old retired engineer who presented with increasing forgetfulness, disorientation, and apathy. While initial concerns were brushed off as “normal aging,” the progression of symptoms soon revealed a different story. He was eventually diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, and by the time of diagnosis, he required assistance with nearly all activities of daily living. His case underscores how severe cognitive impairment often unfolds quietly, escaping early detection and thus delaying intervention.

Another case involved a 58-year-old woman with a history of poorly controlled hypertension and diabetes, who began displaying sudden changes in mood, cognition, and behavior. Imaging revealed multiple small infarcts in the brain consistent with vascular dementia. Unlike the slow, insidious onset of Alzheimer’s, her cognitive decline was abrupt and fragmented, leading to a misdiagnosis of depression until further testing clarified the cause. In this scenario, timely management of cardiovascular risk factors might have delayed the progression toward severe impairment.

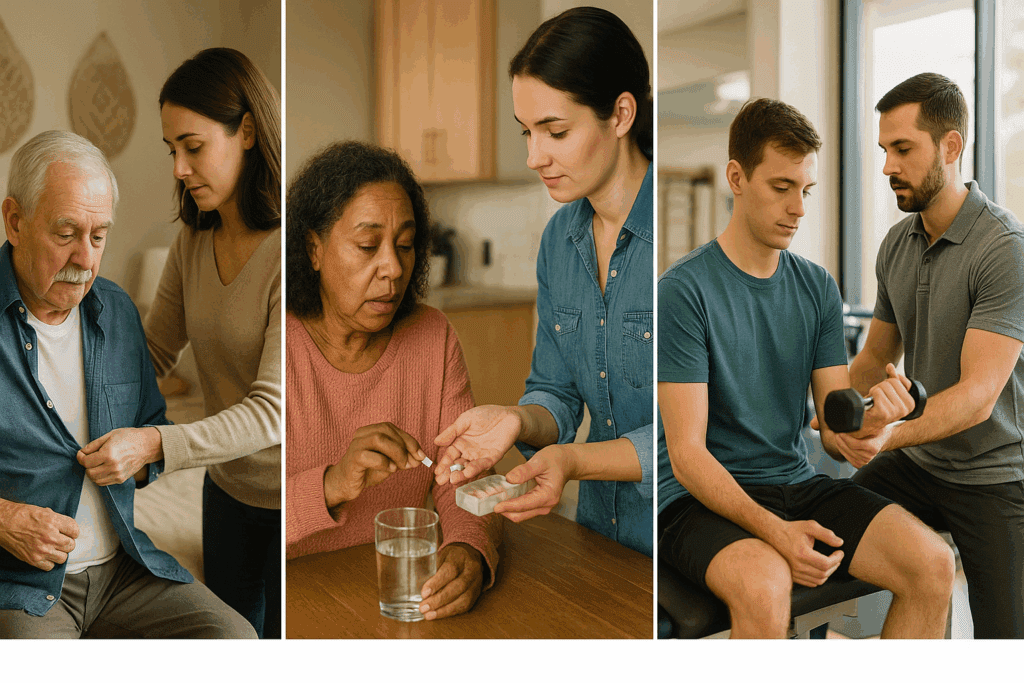

A third example involves a young man in his thirties who suffered a traumatic brain injury in a car accident. While he survived and regained motor function, he was left with severe cognitive impairment that precluded him from resuming employment or managing basic self-care. This case highlights that severe cognitive impairment is not exclusive to the elderly and may result from sudden, catastrophic events. It also demonstrates the lifelong support needs of individuals with such impairments, which may span vocational rehabilitation, occupational therapy, and long-term caregiving.

These severe cognitive impairment examples illustrate the multifaceted nature of the condition and the variety of pathways through which it can manifest. They also emphasize the crucial role of early detection, accurate diagnosis, and a multidisciplinary approach in managing both symptoms and patient quality of life.

The Emotional and Social Dimensions of Severe Cognitive Decline

The clinical definition of severe cognitive impairment may center on functional deficits, but its emotional and social implications reach far deeper. For the individual affected, the loss of autonomy can be profoundly disorienting and demoralizing. Many experience frustration, depression, or anxiety as they confront their diminished capabilities. For caregivers—often spouses, adult children, or close friends—the emotional toll is equally significant. Witnessing a loved one lose their identity and self-awareness is one of the most painful aspects of severe cognitive decline.

Social isolation is another major consequence. As communication becomes impaired and behaviors become unpredictable, friends and even family members may drift away, unsure how to interact or provide support. Over time, this isolation compounds the psychological burden, potentially leading to additional health problems such as depression or chronic stress for both the patient and caregiver.

Furthermore, severe cognitive impairment often entails substantial financial strain. Long-term care, whether in the form of in-home assistance, adult day programs, or residential facilities, can be prohibitively expensive. The indirect costs—including lost income, caregiving time, and out-of-pocket medical expenses—further compound the burden. These pressures can erode family stability and strain relationships, creating an urgent need for social and policy support structures that acknowledge the full impact of cognitive disability.

Addressing these challenges requires not only medical expertise but a compassionate, multidisciplinary approach. Social workers, mental health professionals, occupational therapists, and palliative care teams all play essential roles in supporting individuals and families affected by severe cognitive impairment. Just as no two cases are identical, no single solution suffices; care must be tailored to the individual’s medical needs, psychological profile, family dynamics, and financial resources.

Advances in Research and Treatment: Where Hope May Lie

Despite its daunting nature, severe cognitive impairment is not beyond the reach of scientific innovation. Advances in neuroimaging, biomarker detection, and genetic profiling have ushered in a new era of precision medicine, making earlier and more accurate diagnosis increasingly feasible. Researchers are exploring a variety of therapeutic avenues, from disease-modifying drugs for Alzheimer’s disease to cognitive rehabilitation protocols designed to bolster neuroplasticity.

One promising area of investigation involves monoclonal antibodies that target beta-amyloid plaques in the brain, aiming to slow the progression of Alzheimer’s before it reaches a stage of severe impairment. While some of these treatments remain controversial and carry risks, they represent the first steps toward a future where cognitive decline may not be an inevitable part of aging.

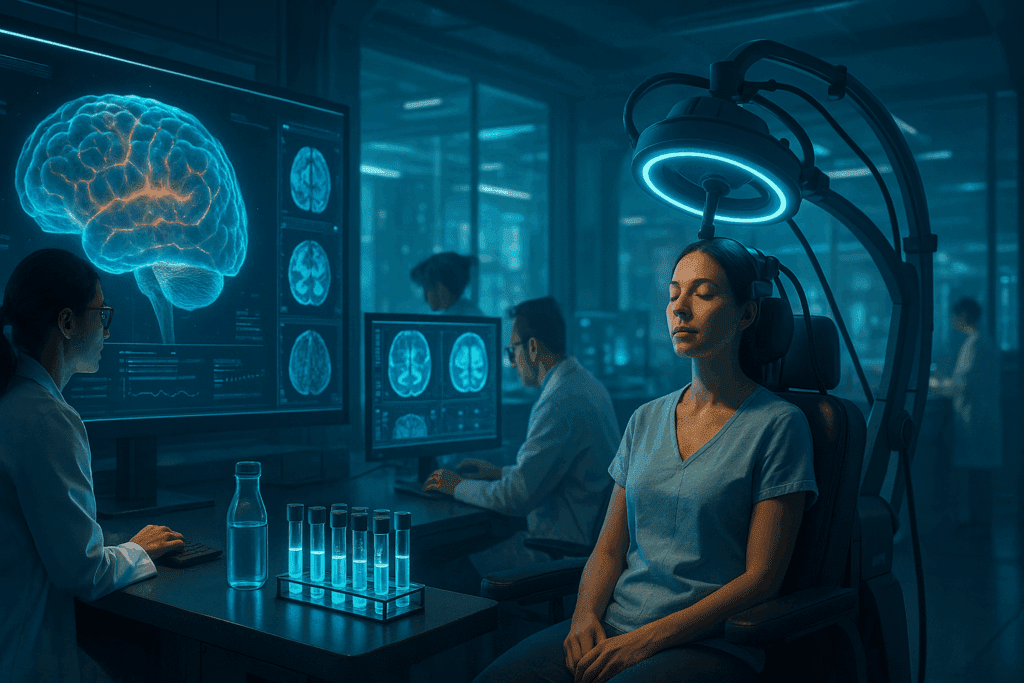

Neurostimulation techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and deep brain stimulation (DBS) are also being explored as adjunct therapies. Although their efficacy in reversing severe cognitive impairment is still under investigation, preliminary results suggest they may enhance certain cognitive functions in select populations. Non-pharmacological approaches—including personalized exercise programs, music therapy, and cognitive training—are also being integrated into care models, offering avenues for improving quality of life even in advanced stages of impairment.

At the intersection of research and practice lies the hope for earlier detection, more effective interventions, and ultimately, a reduction in the global burden of cognitive disease. While we may not yet have a definitive cure, the evolving landscape of neuroscience and geriatric medicine offers a measure of optimism grounded in scientific progress and human resilience.

Frequently Asked Questions: Exploring the Complex Realities of Severe Cognitive Impairment

1. Can severe cognitive impairment be misdiagnosed, and if so, what are the consequences?

Yes, severe cognitive impairment can be misdiagnosed, particularly in its early stages or when overlapping conditions mimic cognitive symptoms. For instance, untreated depression—especially in older adults—can present as pseudo-dementia, leading clinicians to wrongly assume the presence of a neurodegenerative disorder. The consequences of such misdiagnoses can be serious. An incorrect label of severe cognitive impairment may result in unnecessary changes to legal rights, employment status, or living arrangements. Alternatively, failing to diagnose genuine severe cognitive impairment promptly can delay access to appropriate care, support services, and treatment. Real-world severe cognitive impairment examples include patients whose symptoms were initially attributed to stress or normal aging, only to later discover an underlying condition like frontotemporal dementia or hydrocephalus that required vastly different interventions.

2. How does severe cognitive impairment affect a person’s legal and financial autonomy?

Severe cognitive impairment often leads to diminished legal and financial capacity, making it difficult or impossible for individuals to make informed decisions about their affairs. This decline may trigger legal procedures such as the appointment of a guardian or conservator. Families frequently face dilemmas around power of attorney, living wills, and financial planning—issues that are exponentially harder to manage after cognition has already declined. Some of the more tragic severe cognitive impairment examples involve individuals who were financially exploited due to undiagnosed impairment or delayed protective measures. Experts strongly recommend advanced directives and estate planning early on when at-risk individuals still have the capacity to make reasoned decisions, thereby safeguarding their autonomy and wishes.

3. What role do sleep disorders and circadian rhythm disruptions play in the progression of severe cognitive impairment?

Sleep disturbances are both a symptom and a potential risk factor for severe cognitive impairment. Disruptions in the sleep-wake cycle, such as insomnia, fragmented sleep, or excessive daytime sleepiness, can significantly worsen cognitive function. These issues are particularly pronounced in Alzheimer’s patients, where neurodegeneration affects regions of the brain that regulate circadian rhythms. Emerging research suggests that poor sleep may exacerbate amyloid plaque buildup, accelerating the trajectory toward severe cognitive impairment. In clinical settings, severe cognitive impairment examples often include individuals whose nighttime agitation, wandering, or sundowning behaviors become so unmanageable that caregivers are forced to seek residential care solutions.

4. Are there cultural differences in how severe cognitive impairment is perceived and managed?

Cultural beliefs and values significantly influence how families interpret and respond to severe cognitive impairment. In some cultures, memory loss and confusion in older adults are normalized or spiritualized, delaying medical intervention. In others, there may be stigma associated with cognitive decline, discouraging families from seeking help or acknowledging the issue publicly. These cultural frameworks shape caregiving expectations, choices around institutional care, and the degree of emotional burden borne by family members. Certain severe cognitive impairment examples from multicultural clinical practice reveal how miscommunication between providers and families can result in under-treatment or culturally inappropriate interventions. As a result, culturally competent care is essential to managing the nuanced realities of cognitive disorders across diverse populations.

5. What are some non-obvious early warning signs that may precede severe cognitive impairment?

Beyond memory loss and confusion, early indicators of future severe cognitive impairment may include changes in social judgment, personality shifts, or difficulty with complex tasks like driving or financial planning. Subtle language impairments, such as trouble finding words or understanding nuanced conversations, can also serve as red flags. Sometimes, early signs manifest through changes in artistic expression, hobbies, or emotional regulation. While not definitive predictors, these clues warrant further evaluation, particularly in individuals with risk factors like family history or cardiovascular disease. Documented severe cognitive impairment examples show that early detection of these subtle signs can sometimes delay progression through targeted interventions, including cognitive training and lifestyle modifications.

6. How do caregivers experience the emotional burden of supporting someone with severe cognitive impairment?

Caregivers of individuals with severe cognitive impairment frequently report high levels of emotional distress, including burnout, guilt, grief, and social withdrawal. The experience is often likened to an ambiguous loss—where the person is physically present but mentally and emotionally altered. Over time, caregivers may experience chronic stress that impacts their own physical health, sleep, and mental well-being. Support groups, counseling, and respite care are critical components of caregiver health, yet these resources remain underutilized. Many caregivers featured in severe cognitive impairment examples describe the journey as isolating, particularly when friends and family withdraw or misunderstand the nature of the condition. Empathetic, structured support systems are key to sustaining long-term caregiving relationships.

7. What is the connection between cardiovascular health and severe cognitive impairment?

There is a strong and well-documented link between cardiovascular health and the risk of severe cognitive impairment. Conditions such as hypertension, high cholesterol, atherosclerosis, and diabetes contribute to reduced blood flow to the brain, leading to vascular damage and cognitive decline. These factors are particularly associated with vascular dementia, which may appear independently or alongside Alzheimer’s disease. Prevention strategies—including smoking cessation, a Mediterranean-style diet, and regular aerobic exercise—can help mitigate the risk of transitioning into severe cognitive impairment. Real-world severe cognitive impairment examples often involve patients whose cognitive symptoms improved or stabilized when underlying vascular conditions were aggressively managed, underscoring the value of integrative, whole-body approaches to brain health.

8. How do innovations in assistive technology support individuals with severe cognitive impairment?

Assistive technology is rapidly transforming the way severe cognitive impairment is managed, particularly in terms of daily function and safety. Tools like smart home systems, medication reminders, GPS trackers, and voice-activated assistants can extend the time individuals remain independent in their own homes. More advanced applications involve AI-driven monitoring systems that detect changes in behavior or routine and alert caregivers in real time. These tools are not just convenient; they can be life-saving in preventing falls, medication errors, or wandering. Severe cognitive impairment examples in tech-forward healthcare settings illustrate how thoughtfully integrated technology can reduce caregiver burden while preserving patient dignity and autonomy.

9. What are some promising emerging therapies for severe cognitive impairment currently in research?

Beyond traditional medications, several novel therapies are under investigation for their potential to slow or even reverse aspects of severe cognitive impairment. These include gene therapies aimed at correcting mutations associated with early-onset Alzheimer’s, as well as synaptic regeneration strategies using stem cells. Research is also exploring the gut-brain axis and how probiotics or dietary interventions might influence cognitive resilience. Additionally, digital therapeutics—including VR cognitive simulations and computer-based neurofeedback—are showing early promise in rehabilitative settings. While still in experimental phases, these innovations could eventually redefine how severe cognitive impairment is treated. Some early-stage severe cognitive impairment examples from clinical trials hint at small cognitive gains even in advanced stages, offering a glimpse into future possibilities.

10. How can communities become more inclusive and supportive of individuals with severe cognitive impairment?

Building dementia-friendly communities is an essential step in addressing the social marginalization that often accompanies severe cognitive impairment. This includes training first responders, service workers, and local business staff to recognize and respond appropriately to signs of confusion or distress. Accessible public spaces, clear signage, and inclusive programming at community centers can also make daily life safer and more engaging for cognitively impaired individuals. Local governments and nonprofits are increasingly piloting initiatives like memory cafés and mobile clinics to bring services closer to where people live. Documented severe cognitive impairment examples from these programs reveal improved social engagement, reduced caregiver stress, and even delayed institutionalization. A truly inclusive community recognizes cognitive impairment not as an invisible disability but as a shared societal responsibility.

Conclusion: Reflecting on Severe Cognitive Impairment and the Lives It Transforms

Understanding severe cognitive impairment is not simply a matter of academic interest—it is a social imperative. As populations age and neurodegenerative conditions become more prevalent, the need for clear, compassionate, and evidence-based approaches to cognitive health becomes ever more urgent. Recognizing the signs early, seeking appropriate evaluation, and understanding the full spectrum of causes can empower individuals and families to act decisively and compassionately. The integration of real-world clinical experiences with scientific knowledge reveals the profound human dimension of this condition, reminding us that every statistic represents a life profoundly changed.

By reflecting on severe cognitive impairment examples from medical practice, we gain not only technical understanding but also emotional insight into what these changes mean for individuals and those who care for them. From early diagnosis to long-term management, the journey through cognitive decline is complex and multifaceted, requiring patience, empathy, and interdisciplinary collaboration. While challenges abound, so too do opportunities for innovation, advocacy, and above all, human connection. Through continued research, compassionate care, and public awareness, we can offer hope and dignity to those navigating the difficult path of severe cognitive impairment.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out.

Further Reading:

Disclaimer

The information contained in this article is provided for general informational purposes only and is not intended to serve as medical, legal, or professional advice. While Health11News strives to present accurate, up-to-date, and reliable content, no warranty or guarantee, expressed or implied, is made regarding the completeness, accuracy, or adequacy of the information provided. Readers are strongly advised to seek the guidance of a qualified healthcare provider or other relevant professionals before acting on any information contained in this article. Health11News, its authors, editors, and contributors expressly disclaim any liability for any damages, losses, or consequences arising directly or indirectly from the use, interpretation, or reliance on any information presented herein. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of Health11News.