Dementia is a progressive neurological condition that not only affects memory and cognitive function but also deeply influences an individual’s behavior, emotions, and personality. For those living with or caring for someone experiencing cognitive decline, the observable shifts in demeanor and mood can be as distressing as the memory loss itself. The nuanced reality of dementia behaviors, often misunderstood or misattributed, is a crucial area of study and awareness for both caregivers and healthcare professionals. This article explores how personality changes unfold in dementia, the most common and sometimes strange behaviors associated with the condition, and what strategies may help in navigating these changes with compassion and insight.

You may also like: How to Prevent Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease Naturally: Expert-Backed Strategies to Reduce Your Risk Through Lifestyle and Diet

The Complexity of Dementia and Personality Changes

As dementia progresses, personality changes can become prominent, sometimes surfacing even before memory loss is noticed. These shifts are not merely superficial mood swings but profound transformations in how individuals think, feel, and relate to others. A once-outgoing and vivacious person may become withdrawn and apathetic. Conversely, someone previously reserved might grow impulsive or socially uninhibited. These alterations are not conscious choices; rather, they are reflections of neurodegeneration affecting the brain’s frontal and temporal lobes, which regulate behavior, judgment, empathy, and emotional control.

Understanding dementia and personality changes requires a nuanced grasp of how the disease affects brain function. The brain is not a monolithic organ; different areas manage distinct functions. When dementia impacts the prefrontal cortex, for example, individuals may struggle with impulse control and social behavior. When the limbic system is affected, mood regulation falters. These changes can be emotionally challenging for families who feel like they are “losing” the person they once knew, even if that person remains physically present.

Recognizing these personality changes early can be instrumental in managing expectations and planning care strategies. Early signs may include heightened irritability, unusual apathy, increased anxiety, or obsessive routines. These behaviors are not signs of character flaws or emotional weakness; they are medical symptoms. Validating this understanding with medical accuracy is essential to fostering empathy and patience in caregivers and loved ones.

Four Common Dementia Behaviors and What They Reveal

Among the many behavioral symptoms associated with dementia, there are four common behaviors that people with dementia often exhibit. These are agitation, repetitive actions, suspicion or paranoia, and social withdrawal. Each of these behaviors offers a glimpse into the disordered functioning of the brain and reflects unmet needs, discomfort, or cognitive confusion rather than deliberate misbehavior.

Agitation may present as pacing, verbal outbursts, or resistance to care. It often stems from confusion, overstimulation, or physical discomfort that the person cannot express. Repetitive actions, such as tapping, sorting, or repeating questions, can offer a sense of control or predictability in a world that feels increasingly unfamiliar. Suspicion or paranoia may emerge due to memory lapses, where individuals misplace items and believe others are stealing from them. This is not an act of malice but a coping mechanism rooted in the brain’s deteriorating ability to store and retrieve information. Social withdrawal is another telltale sign, often a consequence of both the internal cognitive chaos and an intuitive sense of shame or fear of being judged for declining abilities.

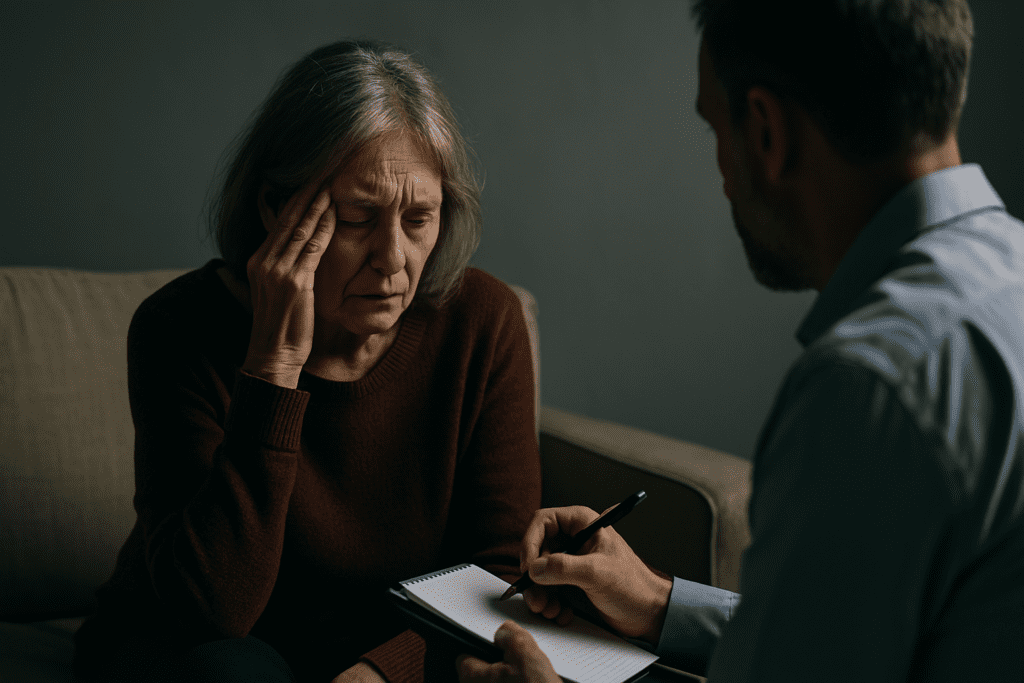

Understanding these dementia behaviors not only improves patient care but also empowers caregivers with the emotional tools to respond with compassion rather than frustration. Instead of correcting or arguing, caregivers can reframe situations, validate feelings, and gently redirect attention, thereby reducing distress for both parties.

Unpacking the Weird Things Dementia Patients Do: Beyond the Surface

To the uninitiated, some behaviors exhibited by those with dementia can appear bizarre, alarming, or even comical. However, these so-called weird things dementia patients do are not merely eccentricities but rather reflections of the brain’s struggle to interpret the environment accurately. An elderly man who begins hoarding tissues or stuffing clothing in unusual places may be attempting to create a sense of safety or maintain a routine that anchors him to familiarity. A woman who suddenly insists that the year is 1965 may be reliving a more emotionally salient time in her life because the neural pathways storing recent memories are compromised.

These actions challenge our assumptions about normalcy and test our ability to respond with empathy. For caregivers, understanding the psychological underpinnings of these behaviors can transform frustration into compassion. When a dementia patient accuses a loved one of being an imposter or claims their long-deceased parent is waiting in the next room, these delusions are rarely deliberate. They are symptomatic of the brain’s faulty data retrieval and processing systems. In some cases, such behavior reflects a regression to earlier developmental stages, not unlike how children engage in fantasy play when constructing their understanding of the world.

Rather than labeling these behaviors as simply weird, it is more constructive to recognize them as manifestations of a deeply altered neurological state. Understanding this allows for more nuanced caregiving and reduces the stigma that often accompanies dementia diagnoses. By reframing these actions as symptoms rather than personal choices, families and caregivers can create more adaptive, respectful care environments.

Understanding the Number One Trigger for Dementia Behavior

Among the various environmental and physiological factors influencing dementia-related behaviors, one question arises frequently: what is the number one trigger for dementia behavior? While individual triggers can vary, one predominant catalyst consistently emerges in clinical literature and caregiver reports—stress due to confusion or overstimulation.

The disorientation that accompanies dementia is not limited to memory loss but extends to spatial awareness, language processing, and time perception. When the world no longer makes sense, and familiar cues become indecipherable, individuals with dementia may respond with aggression, withdrawal, or anxiety. Overstimulation—whether from loud environments, sudden schedule changes, or excessive social interaction—can quickly overwhelm their already taxed cognitive systems. This overload often triggers a cascade of negative behaviors that are, at their core, desperate efforts to regain equilibrium.

Caregivers who recognize stress as a central trigger can take proactive measures to minimize environmental chaos. Strategies may include maintaining a consistent daily routine, simplifying choices, using calm and clear communication, and reducing background noise. These small adjustments, rooted in an understanding of dementia and behavior, can have a transformative impact on day-to-day interactions and the overall well-being of the person with dementia.

Dementia and Mood Changes: Navigating Emotional Instability

One of the most destabilizing aspects of dementia for both patients and their caregivers is the occurrence of rapid, unpredictable emotional shifts. Dementia and mood changes often co-occur, creating a challenging dynamic where a person can go from calm to irate or cheerful to despondent in a matter of minutes. These mood changes are not acts of emotional manipulation but biological responses to a malfunctioning brain.

The mood regulation centers of the brain, particularly within the limbic system, become impaired as dementia progresses. This impairment often results in emotional lability, where sadness, anger, fear, or joy appear suddenly and without clear external cause. For caregivers and family members, this can be deeply unsettling, especially when the mood swing leads to emotional outbursts or verbal aggression. However, by understanding that these emotional responses are not personal attacks but involuntary reactions, caregivers can avoid taking them to heart and instead focus on de-escalation techniques.

Recognizing patterns in mood changes can also help. Are there particular times of day when the person becomes more irritable? Does hunger, fatigue, or noise contribute to their emotional instability? Documenting these variables can inform strategies to prevent or mitigate future episodes. In essence, managing dementia and mood changes requires both a scientific understanding of brain function and an intuitive grasp of the individual’s unique emotional rhythms.

How to Deal with Dementia Mood Swings: Practical Strategies for Stability

For those living with or caring for someone experiencing cognitive decline, one of the most pressing challenges is learning how to deal with dementia mood swings. Unlike ordinary mood fluctuations, which are typically rooted in rational responses to life events, the emotional turbulence associated with dementia can emerge abruptly and seemingly without cause. This unpredictability can create a sense of helplessness in caregivers who feel they are walking on eggshells.

However, there are evidence-based strategies to help manage these emotional shifts. First, establishing a predictable routine can provide a reassuring structure that reduces anxiety and irritability. Routine fosters a sense of safety, which is especially important when cognitive faculties are compromised. Second, adopting a calm, validating approach when mood swings occur can de-escalate tension. Statements such as “I understand this is upsetting” or “I’m here with you” are more effective than logical reasoning, which often fails in moments of emotional distress.

Third, environmental adjustments play a critical role. Reducing clutter, minimizing loud noises, and ensuring proper lighting can help prevent sensory overload. Physical comfort, including hydration, nutrition, and regular sleep, also contributes to emotional stability. If mood swings persist or become severe, medical evaluation may be necessary to rule out contributing factors such as infections, medication side effects, or untreated depression.

Ultimately, learning how to deal with dementia mood swings requires patience, adaptability, and a willingness to meet the individual where they are emotionally rather than where we wish they could be. It’s a dance of empathy and clinical insight, demanding equal parts heart and science.

Dementia and Behavior: Why Understanding Trumps Correction

Too often, dementia-related behaviors are interpreted through a lens of normal cognitive functioning, leading to frustration, miscommunication, and even conflict. When a person with dementia lashes out, repeats questions, or refuses care, it can be tempting to correct or scold. However, such reactions typically exacerbate the situation. A more effective approach begins with a deep understanding of dementia and behaviour as a form of communication.

When language fails, behavior becomes the vehicle for expressing needs, discomforts, and fears. A refusal to bathe may signal a fear of water or an inability to understand the task. An outburst during mealtime may reflect difficulty swallowing or the overwhelming sight of multiple food items on a plate. These behaviors, while distressing, often have a logical underpinning within the framework of cognitive impairment.

Caregivers who reframe behavior as communication rather than rebellion are better equipped to respond constructively. This shift not only improves interactions but also enhances the dignity and emotional well-being of the person with dementia. Through observation, empathy, and experimentation, caregivers can often identify the root cause of behaviors and address them without confrontation.

Moreover, training in dementia behavior management can empower families to adopt interventions that are both compassionate and effective. Whether through support groups, caregiving workshops, or consultation with geriatric specialists, increased education can make a tangible difference in daily caregiving dynamics.

Creating Environments That Support Behavioral Stability

A key component in managing dementia behaviors is the creation of supportive physical and emotional environments. A person with dementia is highly sensitive to environmental cues, and even small changes can trigger confusion or fear. Thoughtful modifications can significantly reduce behavioral challenges and improve quality of life for both the patient and the caregiver.

Lighting should mimic natural daylight as much as possible to regulate circadian rhythms and reduce sundowning, a common evening behavioral issue. Visual cues such as color-coded labels, simplified signage, and contrast-enhanced spaces help reduce spatial confusion. The presence of familiar objects and photos can evoke positive emotions and help ground the person in their identity.

Emotionally, caregivers must foster environments of safety, predictability, and respect. Tone of voice, facial expressions, and body language matter profoundly, often more than the words spoken. A smile, gentle touch, or warm eye contact can calm a person in distress more effectively than any verbal reassurance. This emphasis on emotional congruence—where caregivers align their demeanor with comfort and reassurance—is a cornerstone of best practices in dementia care.

When these principles are consistently applied, they not only reduce the frequency and intensity of dementia behaviors but also restore a sense of agency and humanity to those experiencing cognitive decline. In environments where individuals feel secure and understood, challenging behaviors often diminish in frequency and severity.

Moving Toward Empathy and Understanding in Dementia Care

The journey of caring for someone with dementia is as much emotional as it is physical or logistical. It requires a willingness to embrace the unfamiliar and let go of expectations rooted in who the person once was. Understanding dementia and personality changes is not about resignation but about adaptation—learning to see the person through the lens of compassion and curiosity rather than judgment or grief.

This perspective shift is critical in reducing caregiver burnout and fostering healthier relationships. When caregivers internalize that behaviors are symptoms of disease rather than deliberate acts, they are more likely to respond with grace and creativity. Building this resilience often requires support from community networks, mental health professionals, and continued education in dementia care.

The more society recognizes the humanity within the dementia experience, the more equipped we become to offer care that honors dignity and enhances quality of life. Through informed empathy, we can transform the narrative around dementia from one of loss to one of continued connection and meaningful presence.

Frequently Asked Questions: Understanding Dementia Behaviors and Personality Changes

1. Why do dementia patients often act out in ways that seem out of character?

Dementia can cause fundamental changes in brain function, particularly in areas responsible for judgment, emotional control, and social behavior. This disruption means individuals may no longer be guided by their previous values, inhibitions, or learned social norms. As a result, what may seem like odd or inappropriate actions are often involuntary responses to a confusing internal world. Many caregivers report surprise at the weird things dementia patients do, such as hiding objects, making false accusations, or displaying sudden outbursts. These actions should not be interpreted as deliberate misbehavior, but as symptoms of the complex web of dementia behaviors rooted in neural degeneration.

2. Can hallucinations and delusions be considered part of normal dementia progression?

Yes, hallucinations and delusions are common as dementia advances, especially in conditions like Lewy body dementia or Alzheimer’s disease. These experiences stem from the brain’s inability to distinguish reality from misfired memories or sensory signals. People may see people who aren’t there or become convinced of alternate realities, like believing their spouse is an impostor. These types of dementia behaviors are not always indicative of psychosis in the traditional psychiatric sense but are more about the misprocessing of environmental input. For caregivers, understanding this distinction is essential for managing symptoms calmly and without unnecessary confrontation.

3. What is the number one trigger for dementia behavior in long-term care settings?

In institutional settings like nursing homes, overstimulation is arguably the most common and potent trigger for dementia behavior. Constant noise, frequent staff changes, and unpredictable routines create a stressful environment for those with diminished cognitive filters. Sensory overload, combined with unfamiliarity, can quickly lead to aggression, fear, or withdrawal. When discussing what is the number one trigger for dementia behavior in these environments, it becomes clear that structured calm and predictable routines are crucial. Incorporating soothing music, simplified instructions, and personalized care plans can significantly reduce behavioral outbursts.

4. How do caregivers differentiate between stubbornness and dementia-related resistance?

Distinguishing willful defiance from dementia-induced behavior requires a shift in perception. Dementia often impairs comprehension, memory, and reasoning, which means refusal to bathe or eat may be rooted in confusion or fear rather than stubbornness. For example, a person might not recognize their own reflection or misinterpret a caregiver’s intention, triggering resistance. These dementia and behaviour dynamics are communication attempts, not personal affronts. Training caregivers to reframe these moments can defuse frustration and create more effective, empathetic care responses.

5. Why do some dementia patients develop childlike or regressive behaviors?

Cognitive regression in dementia can mirror aspects of early development due to the deterioration of higher brain functions. As the brain loses its ability to manage complex reasoning, emotional regulation, and memory, individuals may gravitate toward repetitive play, baby talk, or attachment to stuffed animals. These behaviors often fall under the category of weird things dementia patients do, but they can be therapeutic and soothing for the individual. Rather than discouraging these behaviors, validating their emotional comfort value can enhance quality of life. Understanding that these actions serve a psychological purpose is key to respectful and responsive care.

6. How can families prepare for unpredictable dementia and mood changes?

Preparation involves not only logistical planning but also emotional resilience and adaptive strategies. Dementia and mood changes are often erratic and may not follow a clear pattern, making flexibility an essential skill for families. Building a toolbox of calming techniques—such as aromatherapy, distraction activities, and tactile stimulation—can help manage these episodes. Keeping a behavioral journal can also identify subtle triggers that might otherwise go unnoticed. Anticipating rather than reacting to these fluctuations is central to mastering how to deal with dementia mood swings effectively and humanely.

7. Are there cultural or generational factors that influence how dementia behaviors present?

Absolutely. Dementia behaviors can be influenced by cultural norms, generational expectations, and lifelong personality traits. For example, someone raised during wartime may become highly paranoid if they feel unsafe, while someone from a reserved cultural background might withdraw more profoundly than others. The four common behaviors that people with dementia often exhibit—agitation, repetition, paranoia, and social withdrawal—may be amplified or nuanced based on the individual’s upbringing. Tailoring care strategies to account for cultural background enhances understanding and effectiveness in managing behavior.

8. What role does environment play in shaping dementia and personality changes?

Environment plays a pivotal role in either aggravating or soothing dementia and personality changes. Bright lights, loud noises, or complex layouts can heighten anxiety and contribute to disorientation. Conversely, familiar surroundings with personal photos, soft textures, and calming scents can provide grounding and reduce stress. Environmental cues also help mitigate dementia and mood changes by offering non-verbal reassurance. Ensuring consistency in living spaces helps reduce confusion and contributes to emotional stability, making it a critical element of behavior-focused dementia care.

9. Can certain activities help reduce unusual or repetitive dementia behaviors?

Yes, meaningful engagement tailored to the person’s interests and cognitive level can dramatically reduce disruptive behavior. Activities like folding towels, gardening, or listening to era-specific music tap into preserved long-term memory and offer a sense of purpose. Repetitive behaviors, often classified among the four common behaviors that people with dementia often exhibit, can be redirected into constructive outlets. For instance, if someone repeatedly sorts objects, providing a basket of socks to fold may satisfy the same compulsion in a calmer way. Structured activities that echo past routines help maintain dignity and reduce behavioral volatility.

10. What should caregivers keep in mind when responding to emotional volatility in dementia?

Patience, presence, and perception are key. Caregivers must remain emotionally grounded even when facing intense mood swings, which may include crying, shouting, or sudden joy. The emotional landscape of dementia is fragile and often influenced by subtle cues in tone, facial expression, or environment. Understanding how to deal with dementia mood swings involves avoiding confrontation, offering comfort, and providing clear yet gentle communication. Above all, recognizing that these mood changes stem from neurological damage, not personal attacks, allows for care rooted in empathy rather than reactivity.

Conclusion: Recognizing and Responding to Dementia Behaviors with Compassion and Clarity

Navigating the terrain of dementia involves far more than managing memory loss; it calls for a deep understanding of how cognitive decline reshapes personality, behavior, and emotional life. From the weird things dementia patients do to the four common behaviors that people with dementia often exhibit, every action offers insight into an internal world governed by neurological change. Recognizing what is the number one trigger for dementia behavior—confusion and overstimulation—can guide caregivers in crafting environments and routines that soothe rather than agitate. Understanding the connection between dementia and mood changes, and learning how to deal with dementia mood swings effectively, empowers caregivers to reduce emotional volatility with patience and care.

Ultimately, embracing the complex landscape of dementia and behavior enables caregivers and families to shift from correction to understanding, from frustration to empathy. In doing so, we not only enhance the daily lives of those living with dementia but also nurture our own emotional resilience and capacity for compassion. The path is not easy, but it is rich with opportunities for connection, grace, and the kind of love that sees beyond the surface to the enduring humanity beneath.

Alzheimer’s behavioral symptoms, cognitive decline signs, emotional changes in elderly, managing caregiver stress, frontal lobe dementia traits, dealing with elderly aggression, memory loss and confusion, brain function and aging, caregiving strategies for dementia, neurodegenerative disorders behavior, handling elderly delusions, communication tips for dementia care, emotional support for caregivers, late-stage dementia care, recognizing early dementia warning signs, behavioral health in seniors, neurocognitive disorders, personality shifts in elderly, managing sun downing symptoms, aging and brain health

Further Reading:

Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms in Dementia

Changes in Personality Before and During Cognitive Impairment

Disclaimer

The information contained in this article is provided for general informational purposes only and is not intended to serve as medical, legal, or professional advice. While Health11News strives to present accurate, up-to-date, and reliable content, no warranty or guarantee, expressed or implied, is made regarding the completeness, accuracy, or adequacy of the information provided. Readers are strongly advised to seek the guidance of a qualified healthcare provider or other relevant professionals before acting on any information contained in this article. Health11News, its authors, editors, and contributors expressly disclaim any liability for any damages, losses, or consequences arising directly or indirectly from the use, interpretation, or reliance on any information presented herein. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of Health11News.