Paranoia is a distressing and often misunderstood symptom of cognitive decline, particularly in individuals living with dementia. When paranoia becomes a defining feature of a person’s dementia experience, it not only reshapes their perception of reality but also significantly alters their interactions with family, caregivers, and the environment around them. The term “paranoid dementia” is not a formal medical diagnosis but rather a descriptive phrase that captures the deeply unsettling behavioral patterns seen in certain types of dementia where suspicion, delusion, and fear dominate the person’s worldview. One of the most common and emotionally charged manifestations of paranoid dementia involves false accusations of theft, also known as the symptoms of dementia stealing. These distressing suspicions can erode trust, fracture family relationships, and pose significant challenges for caregiving. Understanding the psychological roots, neurological underpinnings, and practical implications of paranoid dementia is essential for developing compassionate and effective approaches to care.

You may also like: How to Prevent Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease Naturally: Expert-Backed Strategies to Reduce Your Risk Through Lifestyle and Diet

Defining Paranoid Dementia and Its Clinical Characteristics

Paranoid dementia describes a constellation of delusional thoughts, mainly involving exaggerated suspicion and fear of being harmed or deceived. While paranoia can emerge in many types of dementia, it is especially pronounced in Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy body dementia, and frontotemporal dementia. What makes paranoid dementia particularly troubling is the persistence and intensity of beliefs that are not grounded in reality. Individuals may believe that their spouse is hiding things from them, that caregivers are intentionally sabotaging their well-being, or that neighbors are conspiring against them. These beliefs are often unshakable, even when presented with logical evidence to the contrary. The symptoms can range from mild distrust to severe delusions that cause extreme distress and behavioral outbursts.

A defining feature of paranoid dementia is that these beliefs are not simply misunderstandings or confusions; they are fixed and deeply internalized. This differs from simple forgetfulness or disorientation, which are more benign aspects of dementia. When a person insists repeatedly that someone is stealing their belongings—even after the item has been found—they are demonstrating one of the classic symptoms of dementia stealing. These delusions often center around familiar people, usually those closest to the individual, which makes caregiving especially difficult and emotionally taxing. The onset of paranoid behaviors may be gradual or sudden, and their progression can fluctuate, often intensifying as dementia advances.

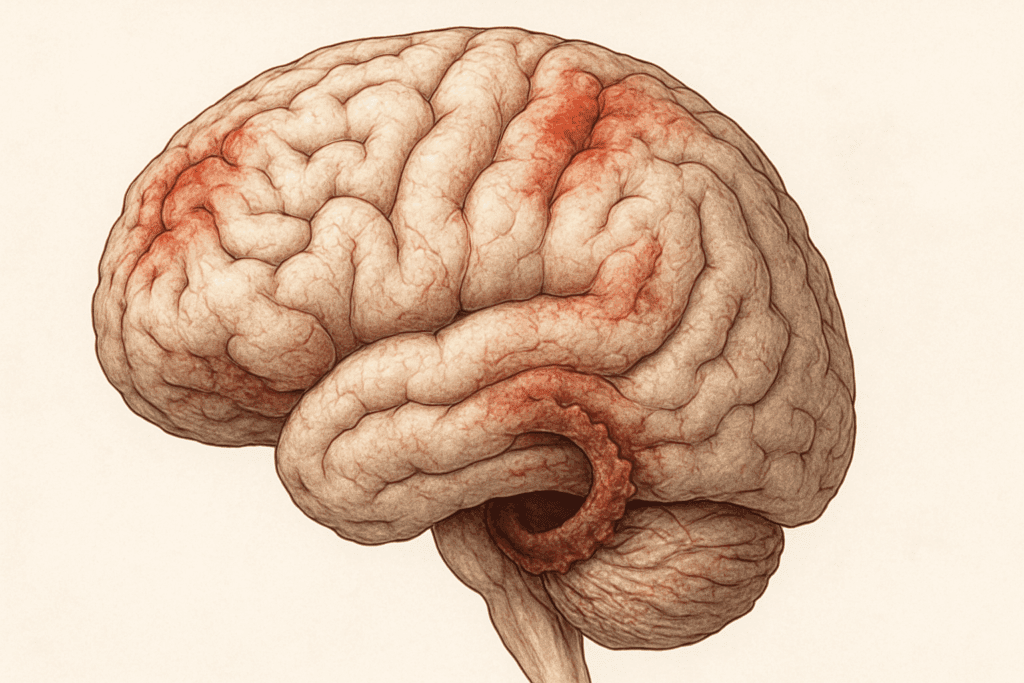

Neurological Foundations of Paranoid Thinking in Dementia

The roots of paranoid dementia lie in the complex interplay between neurological degeneration and emotional vulnerability. As brain structures involved in memory, judgment, and emotional regulation begin to deteriorate, the ability to interpret information accurately becomes compromised. The hippocampus, responsible for forming new memories, and the prefrontal cortex, involved in reasoning and decision-making, are frequently among the first areas to show damage in dementia. This neural degradation sets the stage for cognitive distortions, where gaps in memory are filled with false beliefs.

Compounding this problem is the individual’s inability to recognize their own cognitive deficits—a phenomenon known as anosognosia. When someone with dementia misplaces an object, their brain struggles to retrieve the memory of where they last saw it. Lacking insight into their memory loss, they may instead arrive at the conclusion that someone must have taken it. This cognitive leap is reinforced by emotional distress, often rooted in a broader sense of loss of control and autonomy. Over time, these patterns become ingrained, creating a feedback loop of suspicion and accusation. The symptoms of dementia stealing are particularly pronounced because they strike at the core of perceived threats to personal identity, autonomy, and safety.

The Impact of Paranoia on Daily Life and Family Relationships

Living with paranoid dementia transforms the domestic landscape into a minefield of emotional volatility and mistrust. The home, once a sanctuary, can become a place of fear and suspicion. Family members often find themselves accused of theft, deceit, or betrayal—accusations that can be deeply hurtful, especially when directed at those providing care. These episodes are not just emotionally painful; they can also disrupt daily routines and caregiving tasks. A simple activity like helping someone get dressed can devolve into conflict if the individual believes their clothes have been stolen or hidden.

The symptoms of dementia stealing frequently involve everyday objects: a wallet, a favorite sweater, family heirlooms, or even food. These accusations may repeat daily, despite reassurances or evidence to the contrary. In many cases, the items are simply misplaced, tucked away in unusual locations due to the individual’s impaired memory. Yet for the person with paranoid dementia, the distress is real and overwhelming. Their brain has constructed a narrative to explain the confusion, and that narrative often casts loved ones as villains.

This dynamic can strain even the most resilient relationships. Spouses may feel bewildered and wounded by accusations of infidelity or malice. Adult children, especially those acting as caregivers, may experience guilt, anger, or helplessness. Repeated confrontations can erode emotional bonds and contribute to caregiver burnout. The challenge lies not only in responding to the accusations themselves but in preserving trust, empathy, and emotional balance in the face of relentless psychological turmoil.

Coping Strategies for Caregivers Facing Paranoid Dementia

Supporting someone with paranoid dementia requires a delicate balance of patience, empathy, and strategic intervention. One of the most important principles in dementia care is to avoid direct confrontation. Arguing or trying to convince the person that their beliefs are unfounded often backfires, escalating confusion and agitation. Instead, caregivers are encouraged to enter the person’s emotional reality with validation and reassurance. For example, if a loved one accuses a caregiver of stealing money, a helpful response might be, “That must feel really upsetting. Let’s look together and see if we can find it.”

Creating a predictable and secure environment can also help reduce episodes of paranoia. Clear labeling of drawers, designated places for important items, and minimizing clutter can prevent misplacements that trigger false accusations. Some families have found success with duplicate items—for instance, keeping extra sets of frequently lost items like keys, eyeglasses, or remote controls. This allows caregivers to calmly “find” the missing object, defusing the immediate crisis without fueling the delusional narrative.

Importantly, caregivers must also care for themselves. The emotional toll of repeated accusations and chronic mistrust can be immense. Support groups, therapy, and respite care can provide essential outlets for stress relief and emotional processing. Education is equally critical; understanding that the symptoms of dementia stealing are not personal attacks but manifestations of brain disease can help caregivers maintain perspective and emotional resilience. Through consistent routines, a calm demeanor, and empathetic communication, caregivers can navigate the stormy waters of paranoid dementia with compassion and dignity.

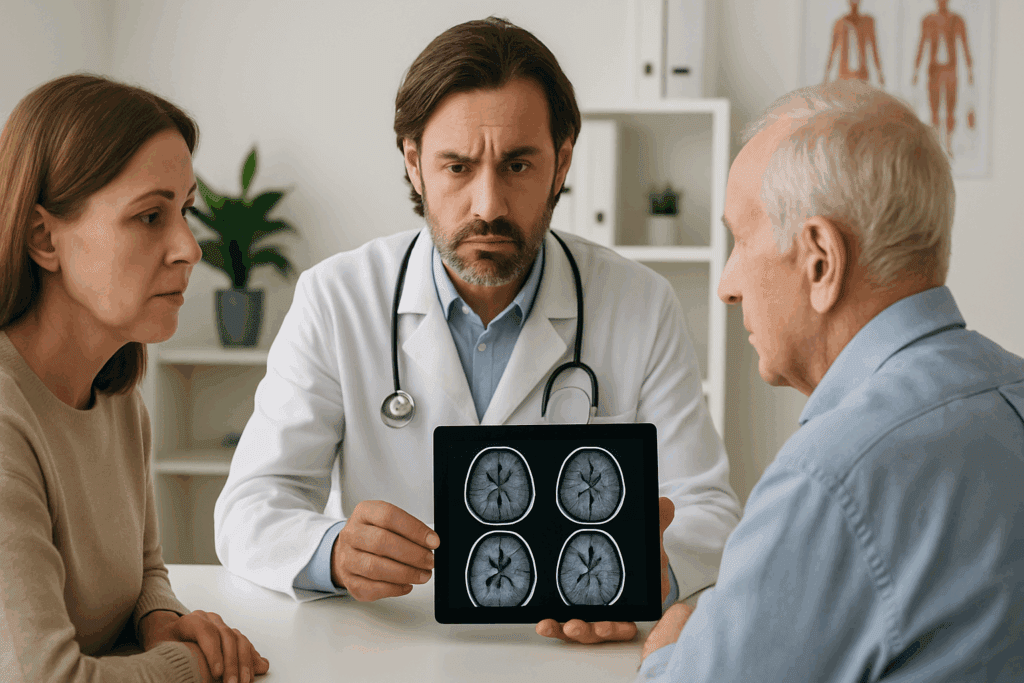

Differentiating Between Dementia and Other Causes of Paranoia

It is essential to distinguish paranoid dementia from other psychiatric or neurological conditions that may also feature delusional thinking. Paranoia is not exclusive to dementia; it is also a hallmark symptom of schizophrenia, delusional disorder, and certain mood disorders with psychotic features. Moreover, acute confusion or delirium—often triggered by infections, medication changes, or dehydration—can produce temporary paranoid symptoms that may mimic those of dementia. Therefore, accurate diagnosis requires a comprehensive assessment by a medical professional, often involving cognitive testing, neuroimaging, and a detailed medical history.

The key distinction lies in the broader cognitive profile. In paranoid dementia, paranoia coexists with memory loss, disorientation, language difficulties, and impaired executive function. These cognitive impairments tend to progress over time, whereas primary psychiatric conditions like schizophrenia may present with preserved memory and cognition outside of active psychotic episodes. Understanding this distinction is crucial because the treatment approaches differ significantly. Antipsychotic medications may be indicated in some cases, but their use in dementia must be carefully weighed due to potential side effects, including increased mortality in older adults.

Additionally, lifestyle and environmental factors can exacerbate paranoia in individuals with dementia. Unfamiliar surroundings, sleep disruptions, sensory impairments, and social isolation can all contribute to feelings of confusion and mistrust. Addressing these modifiable factors can sometimes reduce the frequency and intensity of paranoid episodes, providing a more supportive foundation for care.

Ethical and Practical Challenges in Managing Accusations

When paranoia leads to accusations—particularly those involving the symptoms of dementia stealing—it can create ethical dilemmas and logistical hurdles for caregivers and healthcare providers alike. For instance, how should a caregiver respond when a person with dementia repeatedly accuses a family member of theft? Should caregivers install surveillance cameras to protect themselves from false allegations, or does that violate the individual’s privacy and dignity? These are complex questions with no easy answers.

Professionals often advocate for a person-centered approach, one that respects the dignity of the individual while acknowledging the practical realities of care. Documentation can be a helpful tool—for example, keeping a log of behavioral changes, accusations, and caregiving responses. This not only aids in medical evaluations but can also serve as protection against potential legal or interpersonal disputes. In institutional settings, staff training on dementia-related paranoia is critical to ensure consistent, respectful responses that prioritize safety and compassion.

At the heart of these challenges is the need to preserve the individual’s sense of agency without reinforcing harmful delusions. Strategies such as therapeutic fibbing—offering gentle, comforting explanations rather than strict factual corrections—can help de-escalate situations without compromising care ethics. When used judiciously, these techniques can reduce distress and help maintain a sense of emotional security for the person with dementia.

Looking Ahead: Innovations in Dementia Care and Research

The management of paranoid dementia is an evolving field, informed by ongoing research in neuroscience, psychology, and gerontology. Advances in brain imaging and biomarker identification are enhancing our understanding of the neurological changes associated with paranoia and delusions in dementia. These developments may lead to more targeted therapies in the future, including medications that specifically address the neurochemical imbalances driving paranoid thinking.

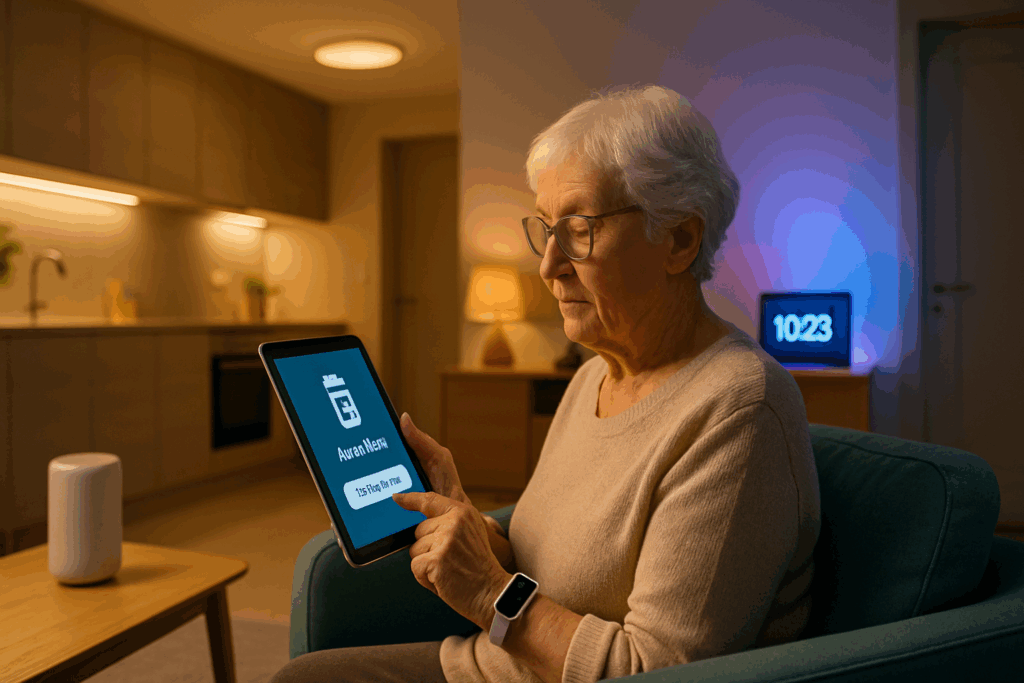

Technology is also playing a growing role in dementia care. Smart home devices, wearable trackers, and digital memory aids can help reduce the confusion and disorientation that often precipitate paranoid episodes. In parallel, innovations in caregiver support—including virtual counseling, AI-based monitoring systems, and immersive training simulations—are equipping families and professionals with better tools to handle the complexities of paranoid dementia.

Furthermore, interdisciplinary research is shedding light on the social and environmental factors that influence paranoia in dementia. Studies suggest that enriched environments, consistent social engagement, and meaningful activities can buffer against feelings of isolation and mistrust. This has led to the development of dementia-friendly communities and memory cafés, where individuals can interact in safe, supportive settings that minimize triggers for paranoia.

Fostering Compassionate Understanding and Resilience

Perhaps the most important lesson from exploring paranoid dementia is the imperative of compassion. Suspicion and accusations are not reflections of moral failings or personal betrayals; they are symptoms of a brain under siege, struggling to make sense of a world that no longer feels coherent. Recognizing this truth can help caregivers, families, and professionals respond with empathy rather than defensiveness.

Cultivating this understanding requires education and dialogue. Raising public awareness about the symptoms of dementia stealing and the emotional turmoil they cause can reduce stigma and foster community support. Encouraging open conversations within families about cognitive health, care planning, and emotional boundaries can also help prepare for the challenges of dementia caregiving.

In the face of an often unpredictable disease, resilience becomes a shared responsibility. It involves equipping caregivers with the tools and support they need to stay grounded and present. It also involves honoring the dignity of those living with dementia, even when their words and actions are shaped by delusion. In this way, we can navigate the difficult terrain of paranoid dementia not only with clinical insight but with human grace.

Frequently Asked Questions: Understanding Paranoid Dementia and the Symptoms of Dementia Stealing

1. How can caregivers build trust when facing repeated accusations of theft due to paranoid dementia?

Establishing trust in the presence of paranoid dementia can be one of the most emotionally taxing aspects of caregiving. One approach is to maintain consistency in routines, tone, and caregiving strategies. People experiencing symptoms of dementia stealing often feel safest in familiar environments where they perceive predictability. Therefore, caregivers can foster security by offering repeated reassurance without trying to challenge the delusion directly. Over time, consistently gentle responses can soften the emotional edge of paranoia and make moments of connection more likely, even if the delusions persist.

2. Are there early warning signs that suggest symptoms of dementia stealing might appear as dementia progresses?

While paranoia can seem to emerge suddenly, there are often early behavioral shifts that precede it. Increased possessiveness, obsessive organization of personal items, or growing discomfort with shared spaces may signal a developing tendency toward suspicion. These behaviors might be dismissed initially as idiosyncrasies, but in the context of progressive memory loss, they can foreshadow the onset of symptoms of dementia stealing. By identifying these patterns early, families can begin implementing supportive routines and documentation strategies before full-blown delusions arise. Recognizing the trajectory of paranoid dementia allows for more proactive and empathetic caregiving.

3. How can technology support families managing paranoid dementia and accusations of stealing?

Emerging technologies can play a vital role in mitigating the distress caused by paranoid dementia. GPS tracking devices can help locate frequently lost items like wallets or keys, reducing the panic that often sparks accusations. Video reminders or automated voice assistants can gently prompt individuals with memory loss, offering context and calming confusion before it escalates. While surveillance must be used cautiously to protect privacy, it can serve a protective role in families where the symptoms of dementia stealing have led to serious conflicts. When deployed ethically, technology can offer structure and security to a situation often ruled by chaos.

4. What are some alternative therapies that may reduce paranoid behavior in dementia patients?

Creative therapies such as music, art, and reminiscence therapy have shown promise in reducing agitation and paranoia. These non-pharmacological interventions provide emotional expression outlets, which may decrease the intensity of paranoid dementia symptoms. For instance, familiar music may help ground a person who is experiencing distress linked to symptoms of dementia stealing by reconnecting them with safe memories. Aromatherapy and pet therapy have also demonstrated benefits in promoting calm and reducing delusional episodes. While these therapies are not cures, they can improve quality of life and help shift focus away from persistent fearful narratives.

5. Can nutrition or dietary changes help with paranoid dementia symptoms?

Although no specific diet can cure dementia, certain nutritional strategies may help stabilize mood and cognitive function, potentially reducing paranoia. Diets rich in omega-3 fatty acids, antioxidants, and B vitamins have been linked to better brain health and slower cognitive decline. While these changes may not eliminate symptoms of dementia stealing, they can support overall neurological resilience. In some cases, vitamin deficiencies—such as B12 or D—can worsen confusion or delusional thinking, and addressing these imbalances may soften paranoid behaviors. Working with a neurologist or dietitian who understands the complexities of paranoid dementia is essential before initiating dietary interventions.

6. How do the symptoms of dementia stealing affect the legal and financial planning process?

Paranoid dementia often involves misplaced accusations that can influence legal relationships and disrupt financial planning. When individuals believe loved ones are stealing from them, they may revoke power of attorney, refuse to sign important documents, or contest estate plans. These conflicts can escalate rapidly, especially when the symptoms of dementia stealing persist despite documentation and reassurances. Families are advised to initiate legal planning early—ideally before symptoms of paranoia emerge—so that decisions are made with full mental capacity. Consulting with elder law attorneys can help safeguard against legal challenges that may arise as the condition progresses.

7. How can professionals differentiate paranoid dementia from age-related suspicion or general forgetfulness?

Distinguishing paranoid dementia from normal aging requires a nuanced clinical approach. While some degree of suspicion may emerge with age, especially in response to sensory decline or social isolation, paranoid dementia is marked by persistent, fixed delusions that impair daily functioning. When symptoms of dementia stealing recur in the absence of logical triggers and persist despite reassurance or resolution, they are more likely linked to a pathological cognitive decline. Professionals often rely on cognitive testing, behavioral observations, and reports from caregivers to establish patterns consistent with paranoid dementia. The chronicity and emotional charge behind the suspicion also help distinguish it from more benign forgetfulness.

8. How can family members maintain emotional health when falsely accused?

Repeated accusations—especially those tied to the symptoms of dementia stealing—can create profound emotional strain. It is essential for caregivers and family members to acknowledge the toll this dynamic takes and seek emotional support. Therapy, peer support groups, and regular respite care can help individuals process the guilt, anger, and grief that accompany paranoid dementia caregiving. It’s also helpful to establish clear internal boundaries—reminding oneself that the accusations stem from neurological disease, not personal betrayal. Over time, emotional detachment from the accusation, while maintaining compassionate care, becomes a vital survival tool.

9. Are there cultural factors that influence how paranoid dementia is expressed or understood?

Yes, cultural background significantly shapes how paranoid dementia is interpreted, managed, and expressed. In some cultures, mental health symptoms are stigmatized or interpreted through spiritual or moral frameworks, which may delay recognition of symptoms like dementia stealing. Others may normalize suspicious behavior in elders as part of aging, overlooking its pathological roots. Additionally, the targets of accusations may vary depending on family hierarchy and social norms—caregivers from outside the family may be more frequently accused in cultures emphasizing familial caregiving roles. Understanding these cultural nuances is vital for clinicians and caregivers working in diverse settings to ensure culturally sensitive, effective care.

10. What are some long-term care strategies for managing paranoid dementia in residential settings?

Long-term care facilities face unique challenges when supporting residents with paranoid dementia. Staff must be trained to recognize the symptoms of dementia stealing and respond with empathy rather than correction. Secure storage of personal items, regular inventory checks, and personalized care plans can minimize accusations. Establishing continuity in staff assignments can also reduce suspicion, as familiar caregivers tend to evoke less fear. Moreover, facilities can incorporate environmental design strategies—such as memory boxes outside rooms or personalized closets—to help residents feel a greater sense of control and reduce the likelihood of delusional beliefs taking hold. Ultimately, managing paranoid dementia in institutional settings requires a balance of structure, familiarity, and emotional validation.

Conclusion: Embracing the Complexity of Paranoid Dementia with Insight and Compassion

Paranoid dementia represents one of the most emotionally fraught and clinically complex expressions of cognitive decline. The persistent suspicion, fear, and accusations—especially the symptoms of dementia stealing—can disrupt relationships, impair caregiving efforts, and deepen emotional suffering for everyone involved. Yet through education, compassionate care, and an informed understanding of the underlying neurological processes, families and professionals can find pathways to connection and healing.

By approaching paranoid dementia with empathy and strategy, we not only improve the quality of life for those affected but also cultivate a caregiving environment rooted in patience, resilience, and respect. In doing so, we reaffirm the humanity of individuals whose perceptions may be altered by disease but whose need for love, safety, and understanding remains unchanged. As research continues to illuminate the intricacies of paranoia in dementia, our collective responsibility is to translate that knowledge into actions that uplift and protect the most vulnerable among us. In the end, understanding paranoid dementia is not just a clinical task—it is a moral one, calling on our deepest reserves of compassion and care.