Vision, one of our most essential senses, is often thought of in purely mechanical terms: light enters the eye, the brain processes the image, and we see. But when the brain begins to deteriorate—as it does in neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s disease—the impact on vision can be profound and multifaceted. While memory loss tends to dominate conversations around Alzheimer’s, emerging research reveals that visual processing issues may serve as some of the earliest signs of cognitive decline. Recognizing these symptoms is crucial for early intervention. Indeed, weird vision problems in early Alzheimer patients are no longer considered anomalies, but increasingly understood as indicators of deeper neurological dysfunction.

You may also like: How to Prevent Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease Naturally: Expert-Backed Strategies to Reduce Your Risk Through Lifestyle and Diet

The Complex Relationship Between Vision and Brain Function

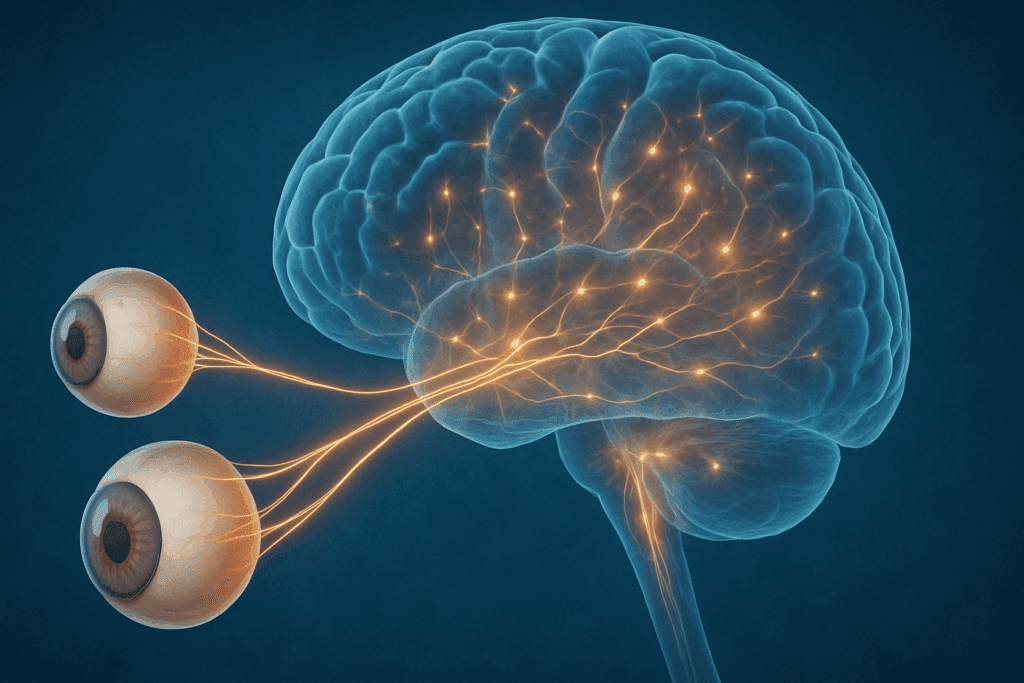

To fully appreciate how Alzheimer’s affects vision, it’s important to understand the intricate relationship between the eyes and the brain. Contrary to popular belief, the eyes themselves do not “see.” Instead, they function as sophisticated cameras, capturing light and sending it via the optic nerve to various parts of the brain for processing. The occipital lobe, located at the back of the brain, plays a primary role in interpreting visual information. However, higher-order visual processing also involves the temporal and parietal lobes, which interpret motion, spatial relationships, and object recognition.

When Alzheimer’s disease begins to alter brain tissue, particularly in these regions, visual disturbances can emerge well before memory issues become evident. These are not merely blurry vision or difficulty focusing—problems commonly associated with aging or eye disease—but rather distortions in how the brain interprets visual data. Such distortions can lead to bizarre perceptual experiences, including misidentification of objects, difficulty judging distances, or the inability to recognize familiar faces.

Understanding Weird Vision Problems in Early Alzheimer’s

The phrase “weird vision problems early Alzheimer” may sound vague, but it captures the unsettling nature of the visual anomalies patients may face. Unlike traditional eye disorders like cataracts or glaucoma, these vision problems originate in the brain and often evade standard ophthalmological assessments. One of the hallmark signs is difficulty with visual contrast sensitivity—for example, trouble distinguishing objects from similarly colored backgrounds. This can make navigation around the home more dangerous, as steps, furniture, and even doorways become visually camouflaged.

Another early sign is difficulty with spatial awareness. Individuals might reach for objects and consistently miss, pour liquids inaccurately, or bump into walls and furniture. This impairment is often mistaken for clumsiness or aging-related decline, delaying proper diagnosis. More concerning is the phenomenon of visual agnosia, in which patients can see but cannot interpret what they are seeing. For example, a person might look at a toothbrush and not recognize it as an object used for cleaning teeth. This represents a breakdown not in sight but in recognition—a subtle yet telling indicator of Alzheimer’s impact on cortical processing.

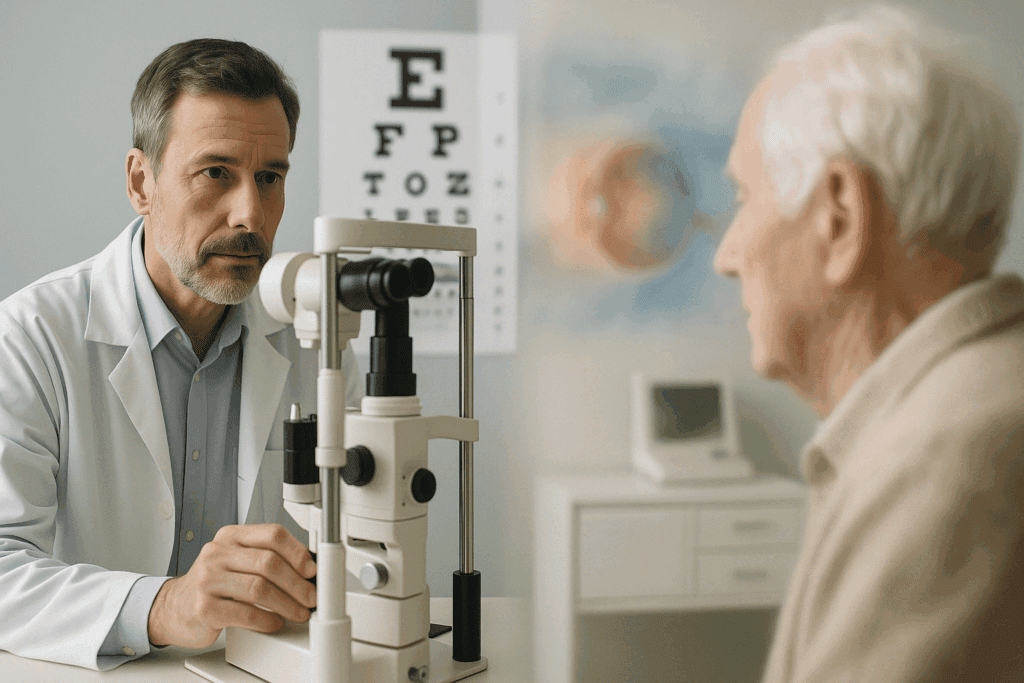

Alzheimer Vision Problems: Beyond the Eyes

As these vision problems are rooted in neurological degeneration rather than ocular disease, they often go undetected in regular vision tests. Optometrists and ophthalmologists may declare a patient’s vision to be “perfectly fine,” even as the patient struggles with profound perceptual difficulties. Alzheimer vision problems challenge the conventional boundary between neurology and ophthalmology. In clinical practice, these issues underscore the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration, as optometrists, neurologists, and geriatricians must work together to identify the subtle interplay between visual symptoms and cognitive decline.

In some cases, Alzheimer’s patients may experience hallucinations, typically visual rather than auditory. These hallucinations often appear in the later stages but can occasionally occur earlier, particularly in individuals with Lewy body dementia, a condition that shares many symptoms with Alzheimer’s. Hallucinations are another example of how the brain’s misinterpretation of visual stimuli can manifest in ways that seem strange or surreal. Recognizing these unusual visual experiences as neurologically based rather than purely psychiatric is essential for accurate diagnosis and compassionate care.

The Role of Posterior Cortical Atrophy in Visual Decline

Posterior Cortical Atrophy (PCA) is a lesser-known but particularly relevant subtype of Alzheimer’s disease that predominantly affects the posterior regions of the brain, including the occipital and parietal lobes. Patients with PCA often present with vision-related symptoms before memory loss becomes apparent, making them a key population in understanding the intersection of vision and cognitive decline. These individuals may experience difficulties with reading, navigating spaces, and processing complex visual environments. The peculiar nature of these symptoms often leads to misdiagnosis, sometimes as primary visual impairment or psychiatric conditions, further complicating the patient’s path to appropriate care.

In many PCA cases, individuals become increasingly anxious due to their declining ability to interpret the world visually. They may avoid driving, withdraw from social situations, or become overly dependent on caregivers. Understanding that these behaviors stem from neurologically based vision loss—not stubbornness or laziness—can dramatically change how caregivers and clinicians support the patient.

Real-World Implications and Risks

One of the most concerning aspects of Alzheimer vision problems is their potential impact on daily safety. Patients may misjudge distances while crossing streets, mistake reflections for objects, or perceive motion where there is none. These distortions elevate the risk of accidents and falls, which are already a major concern for aging populations. Additionally, these vision issues can affect reading comprehension, television viewing, and other activities that form the basis of daily routine and personal enjoyment.

The misinterpretation of faces and expressions—a condition known as prosopagnosia—can further erode social connections. When a person can no longer recognize family members or friends by sight, the resulting confusion and embarrassment may lead them to withdraw, exacerbating isolation and depression. This cycle of declining vision and reduced engagement highlights how early intervention is not merely a clinical objective but a profoundly human imperative.

Diagnostic Challenges and Clinical Screening

Traditional diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s focus heavily on memory impairment, but the increasing recognition of visual processing deficits has prompted calls for a more comprehensive approach. Neuropsychological assessments now often include visuospatial testing, which evaluates a patient’s ability to understand spatial relationships and navigate visual environments. Imaging technologies such as MRI and PET scans can reveal atrophy in specific brain regions responsible for visual interpretation, providing further diagnostic clarity.

Yet these tools are not always accessible or affordable. Many cases continue to go unrecognized until the disease has progressed significantly. Advocates argue for greater awareness among primary care physicians and routine inclusion of vision-related questions during cognitive evaluations. Questions such as “Have you noticed any difficulty in reading signs?” or “Do you often bump into furniture?” can serve as gateways to deeper investigation. While these may seem minor complaints on the surface, they could point to weird vision problems associated with early Alzheimer, warranting further exploration.

Differentiating Alzheimer Vision Problems from Normal Aging

It is essential to distinguish between vision changes that are part of normal aging and those that may signal neurological disease. Presbyopia, for example, is a common age-related condition that affects the eye’s ability to focus on close objects. Similarly, cataracts and macular degeneration can cause blurriness and reduced acuity. These conditions are mechanical in nature and largely treatable with corrective lenses or surgery. In contrast, the visual disturbances linked to Alzheimer’s do not stem from the eyes themselves but from how the brain interprets visual signals.

Understanding this distinction can be deeply reassuring for patients experiencing vision changes. A thorough evaluation by both an eye care professional and a neurologist can help parse out whether a person is dealing with typical aging or something more serious. In families with a history of Alzheimer’s or other neurodegenerative diseases, being especially vigilant about unusual visual symptoms may facilitate earlier detection and intervention, potentially altering the disease trajectory.

Promising Advances in Research and Technology

Emerging research continues to explore how biomarkers and imaging techniques can improve early detection of Alzheimer-related vision issues. Studies using functional MRI (fMRI) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) are helping researchers visualize the subtle structural and functional changes in both the brain and retina. Intriguingly, the retina—as an extension of the central nervous system—may offer a non-invasive window into early Alzheimer pathology. Researchers are investigating whether retinal thickness or changes in retinal blood flow could serve as early biomarkers for cognitive decline.

Artificial intelligence is also being leveraged to detect patterns in vision tests and retinal scans that may be imperceptible to the human eye. These technologies could one day be deployed in routine vision screenings, flagging patients who may benefit from further cognitive evaluation. While still in early stages, these tools underscore the vital importance of recognizing weird vision problems in early Alzheimer not as peripheral oddities, but as central clues in the diagnostic puzzle.

Supporting Patients and Caregivers

Once vision-related symptoms of Alzheimer’s are recognized, supportive strategies can make a significant difference in quality of life. Modifying the home environment to enhance contrast—for instance, using dark-colored rugs on light floors—can improve navigation. Labeling items with large, bold fonts and simplifying visual environments can reduce confusion and frustration. Orientation aids such as clocks, calendars, and signage also help patients maintain autonomy longer.

Equally important is caregiver education. When caregivers understand that a patient’s behaviors stem from Alzheimer vision problems rather than defiance or inattention, their responses become more compassionate and effective. For example, instead of reprimanding a loved one for ignoring a glass of water on the table, a caregiver might experiment with colored cups or repositioning the item for greater visibility. These small adjustments can significantly ease daily interactions and preserve dignity.

The Broader Implications for Public Health

The growing recognition of visual symptoms in Alzheimer’s has broad implications for public health policy. As the global population ages, early diagnosis and intervention become critical not only for individual well-being but also for reducing the long-term burden on healthcare systems. Including visual screening questions in annual wellness visits for seniors could be a cost-effective strategy to catch early cognitive decline. Community outreach programs can also raise awareness, encouraging individuals and families to seek help at the first sign of unusual vision issues.

Training healthcare professionals to recognize the signs of Alzheimer vision problems and integrate them into holistic assessments can improve diagnostic accuracy. This shift from a memory-centric model to a broader neurological framework reflects a more nuanced understanding of how Alzheimer’s manifests and progresses. Ultimately, such efforts align with the principles of preventive medicine: detect early, intervene wisely, and support comprehensively.

Frequently Asked Questions: Exploring Weird Vision Problems and Alzheimer’s Early Signs

1. Can weird vision problems in early Alzheimer affect color perception or brightness sensitivity?

Yes, weird vision problems in early Alzheimer can impact how individuals perceive color and brightness. Some people may find that certain shades blend together or that bright lights become overwhelming, even painful. This isn’t an issue with the eyes themselves but rather with how the brain interprets visual data. Research suggests that changes in the occipital and parietal lobes, which are responsible for processing visual stimuli, can distort how colors and brightness are perceived. This altered perception can interfere with daily activities, such as cooking or reading, where color contrast is crucial, and may serve as an early indicator of underlying Alzheimer vision problems.

2. Are Alzheimer vision problems linked to driving difficulties before memory loss becomes evident?

Absolutely. One of the underrecognized dangers of weird vision problems in early Alzheimer is how they affect driving. Patients may misjudge distances, overlook road signs, or fail to see pedestrians, especially in low-contrast situations like dusk. Even if memory seems intact, these visual misinterpretations can make driving extremely hazardous. It’s critical for caregivers and clinicians to monitor not just cognitive decline but also changes in visual-spatial abilities, which are often among the first Alzheimer vision problems to appear and can severely compromise road safety.

3. How do Alzheimer-related visual issues impact reading and literacy skills?

Alzheimer vision problems can erode reading ability in subtle ways. Patients may skip lines, misread words, or struggle with text tracking, which makes comprehension frustrating. These issues are not about blurry vision but about how the brain organizes visual information—like decoding the sequence of letters or understanding the spatial structure of a paragraph. Weird vision problems in early Alzheimer often mimic dyslexia-like symptoms, creating challenges that are easily misattributed to fatigue or attention deficits. Adaptive tools like audiobooks or large-print materials can provide relief, but early identification remains key to preserving reading skills.

4. Can weird vision problems in early Alzheimer contribute to social withdrawal?

Yes, and often in ways that aren’t immediately obvious. Individuals with Alzheimer vision problems may avoid social gatherings not because they are forgetful, but because they struggle to recognize faces or interpret expressions. This creates anxiety in group settings where visual cues play a major role in communication. Over time, these difficulties can lead to embarrassment and voluntary isolation, which may be mistaken for depression or apathy. Recognizing that weird vision problems in early Alzheimer can drive social retreat underscores the need for sensitive, personalized support strategies.

5. Is there any connection between Alzheimer vision problems and illusions or mirror misidentification?

Indeed, visual illusions and mirror misidentification are classic examples of how the brain misinterprets visual input in Alzheimer’s. Someone might mistake their reflection for a stranger, or perceive shadows as threatening objects. These are more than hallucinations—they are manifestations of a disordered visual-cognitive interface. Weird vision problems in early Alzheimer can progress to these phenomena as the disease affects deeper visual integration centers. Understanding these behaviors as neurological rather than psychiatric in origin is crucial for both accurate diagnosis and compassionate caregiving.

6. How can eye-tracking technology help detect Alzheimer vision problems earlier?

Eye-tracking is emerging as a promising tool for identifying weird vision problems in early Alzheimer. By monitoring how the eyes move when scanning a scene or reading text, clinicians can detect abnormalities in attention, focus, and spatial navigation long before memory symptoms emerge. These subtle eye movement patterns often correlate with early brain changes seen in Alzheimer’s, especially in the parietal lobes. Integrating eye-tracking into vision screenings could offer a non-invasive, cost-effective way to flag early Alzheimer vision problems. Though still in the research phase, this technology is poised to revolutionize how we detect cognitive decline.

7. Are there specific tasks or activities that can highlight early Alzheimer vision symptoms?

Yes, tasks that involve hand-eye coordination, depth perception, or spatial judgment are particularly telling. For example, setting a table, reaching for objects, or navigating uneven terrain may become surprisingly difficult. These tasks often expose weird vision problems in early Alzheimer that go unnoticed during routine eye exams. Caregivers might observe frequent spills, hesitation when stepping down stairs, or confusion in familiar environments. Tracking performance on these activities over time can provide valuable insight into the emergence of Alzheimer vision problems and prompt earlier neurological evaluations.

8. Do people experiencing Alzheimer vision problems usually know something is wrong?

Not always. Some individuals are aware that their vision feels “off,” but they may not have the language to articulate what’s wrong. Others may blame their glasses, lighting, or even accuse loved ones of moving things around. This lack of insight, known as anosognosia, can complicate diagnosis and delay treatment. However, when weird vision problems in early Alzheimer are acknowledged by patients, it often opens a door for early intervention. Validating their experience and encouraging further evaluation without fear or stigma can be life-changing.

9. How do Alzheimer vision problems influence balance and fall risk?

Alzheimer vision problems can significantly impair depth perception and spatial orientation, two key components of balance. As a result, patients may feel disoriented when walking or navigating tight spaces, leading to a higher risk of falls. These risks are exacerbated in dim lighting or unfamiliar environments. Weird vision problems in early Alzheimer may also alter a person’s confidence, making them overly cautious or, paradoxically, unaware of the danger. Occupational therapy interventions that focus on visual-spatial training can help mitigate these fall risks and preserve mobility.

10. What are the future directions for diagnosing Alzheimer through vision-based biomarkers?

The future of Alzheimer diagnostics may lie in the retina. Scientists are studying whether retinal imaging can reveal biomarkers such as amyloid plaques or changes in blood flow that mirror what’s happening in the brain. Because the retina is part of the central nervous system, it offers a unique, non-invasive window into early neurodegeneration. These advancements could allow for earlier identification of weird vision problems in early Alzheimer before cognitive symptoms dominate. As technology progresses, integrating vision-based biomarkers into routine health screenings may become a standard practice in dementia prevention strategies.

Conclusion: Why Recognizing Vision-Related Alzheimer Symptoms Matters More Than Ever

Understanding and identifying weird vision problems in early Alzheimer is more than a clinical consideration; it is a compassionate response to a complex disease. These visual anomalies often represent the brain’s early cries for help—subtle distortions in perception that precede the more widely recognized symptoms of memory loss. By paying attention to how patients see the world, both literally and metaphorically, we can intervene sooner and more effectively.

The path to early detection lies not only in advanced imaging or sophisticated biomarkers but also in a heightened awareness of symptoms that fall outside conventional expectations. Weird vision problems may initially seem unrelated to cognition, but their presence can reveal the very earliest signs of Alzheimer’s disease. Recognizing these disturbances as legitimate, neurologically rooted concerns empowers both clinicians and caregivers to act sooner, support better, and plan more effectively.

As research progresses, the hope is that vision-based screenings will become an integral part of cognitive health assessments. Until then, staying informed and vigilant remains our best defense. The eyes may not lie—but sometimes, it is the brain behind them that tells the most crucial story.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out.

Further Reading:

Alzheimer’s may begin with unusual vision problems, study finds

Could Bizarre Visual Symptoms Be a Telltale Sign of Alzheimer’s?

Disclaimer

The information contained in this article is provided for general informational purposes only and is not intended to serve as medical, legal, or professional advice. While Health11News strives to present accurate, up-to-date, and reliable content, no warranty or guarantee, expressed or implied, is made regarding the completeness, accuracy, or adequacy of the information provided. Readers are strongly advised to seek the guidance of a qualified healthcare provider or other relevant professionals before acting on any information contained in this article. Health11News, its authors, editors, and contributors expressly disclaim any liability for any damages, losses, or consequences arising directly or indirectly from the use, interpretation, or reliance on any information presented herein. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of Health11News.