Stretching is often promoted as an essential element of any well-rounded fitness regimen. Whether it’s a dynamic warm-up before exercise or a deep static stretch to cool down, stretching is seen as beneficial for flexibility, joint health, and injury prevention. But one question that frequently arises is: Is it normal to be sore after stretching? For many, this sensation can be confusing or even concerning, especially when the soreness feels similar to what one might experience after a strenuous workout. In this in-depth article, we explore the science behind stretching-related muscle soreness, the role stretching plays in recovery, and how to distinguish between healthy discomfort and potential injury. Along the way, we’ll clarify why stretching can hurt, when soreness might signal overstretching, and how to stretch in ways that support long-term flexibility, mobility, and musculoskeletal health.

You may also like : Best Stretches for Sore Legs and Tight Thigh Muscles: How to Relieve Upper Leg Pain Safely and Naturally

Understanding Stretching-Induced Muscle Soreness

Soreness from stretching may feel counterintuitive at first. After all, stretching is intended to ease tension and improve mobility, not create pain or discomfort. Yet many people report being sore after stretching, particularly when trying a new routine, increasing intensity, or engaging in deeper or more advanced stretches. So, does stretching make you sore, and if so, why?

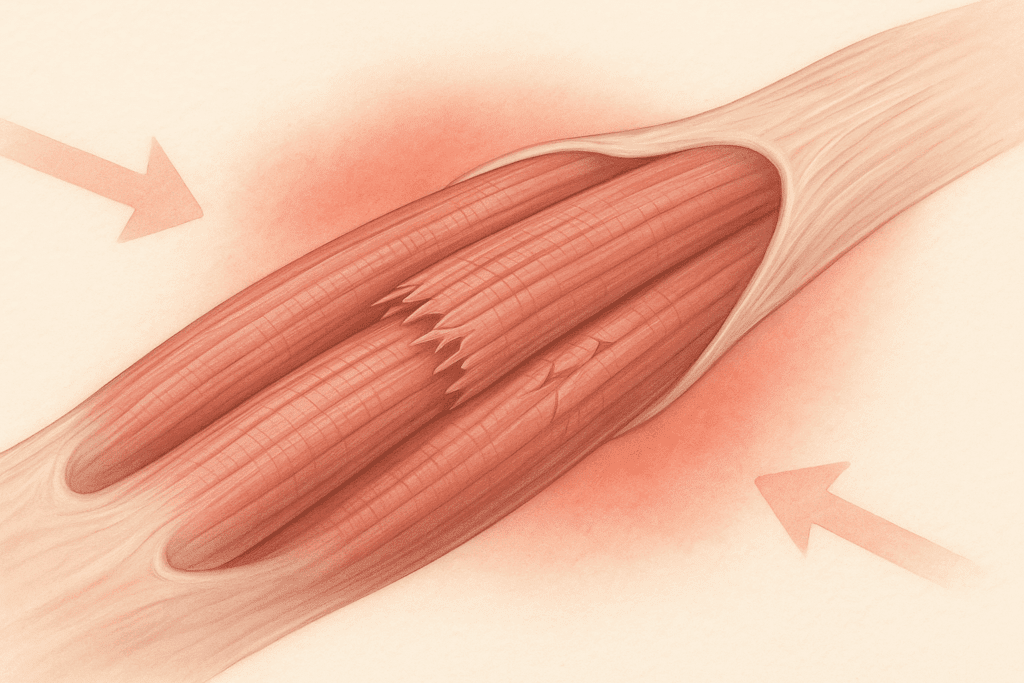

The answer lies in the physiological response of muscles and connective tissues to elongation. When a muscle is stretched beyond its usual range, microscopic tears can occur in the muscle fibers or surrounding fascia. This process is not unlike the mechanism behind delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS), which results from eccentric loading during resistance training. Although stretching generally doesn’t produce the same magnitude of tissue damage as weightlifting, it can still create enough strain to trigger an inflammatory response. That inflammation, while part of the body’s natural healing process, can lead to temporary soreness.

Moreover, soreness from stretching is more likely when the tissue is not adequately warmed up. Cold muscles are less pliable and more susceptible to injury. That’s why experts recommend engaging in light aerobic activity before stretching and gradually increasing the intensity of stretches. When someone asks, “Why am I sore after stretching?” the most common explanation is insufficient warm-up, overstretching, or unfamiliar movement patterns that introduce novel stress to the body.

What Does Stretching Do for Recovery?

Stretching is often associated with post-exercise recovery, but its role in that process is more nuanced than commonly believed. One of the key benefits of stretching is increased blood flow to muscles. Enhanced circulation helps deliver oxygen and nutrients while removing metabolic waste products such as lactic acid. This physiological support can facilitate recovery, reduce muscle stiffness, and enhance the body’s ability to bounce back after strenuous activity.

Yet despite these mechanisms, scientific studies show mixed results when it comes to stretching’s direct impact on reducing muscle soreness. Some research suggests that stretching after exercise has little effect on preventing DOMS, while other studies note modest benefits in perceived soreness and flexibility. So, does stretching help sore muscles? The answer is not a straightforward yes or no. While stretching may not eliminate soreness, it can aid in promoting mobility and maintaining functional range of motion, which are critical for long-term musculoskeletal health.

Importantly, stretching during recovery may offer psychological benefits as well. For many individuals, gentle stretching after exercise promotes a sense of relaxation and body awareness. These effects can improve adherence to a recovery routine and contribute to a holistic approach to fitness. In this way, what stretching does for recovery may be as much about enhancing the mind-body connection as it is about facilitating physiological repair.

Stretching and Connective Tissue Remodeling

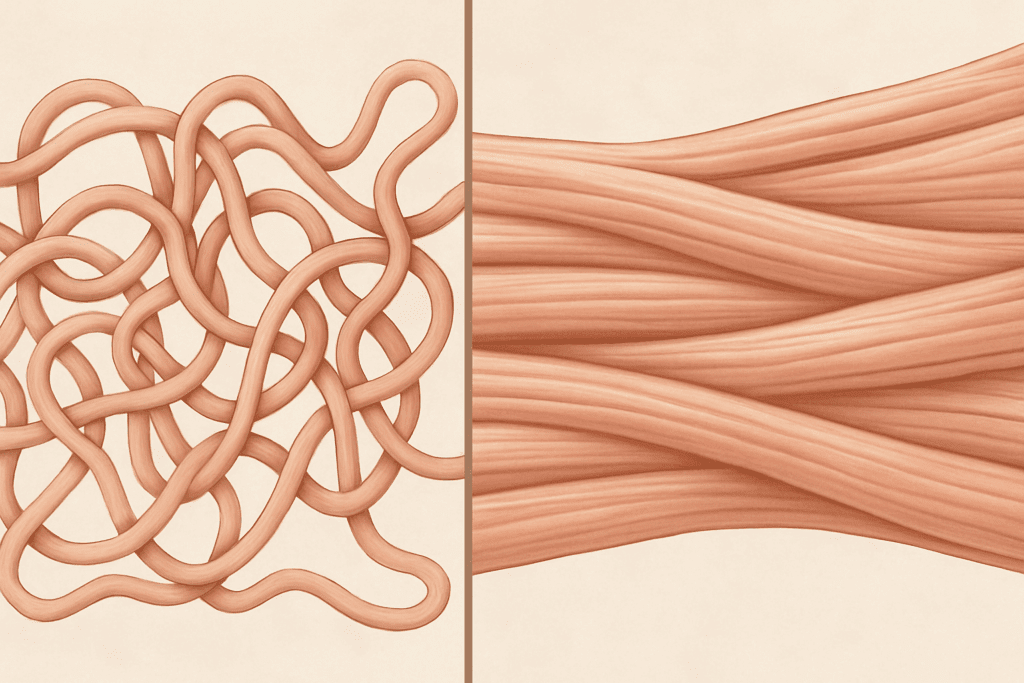

One of the lesser-known effects of repeated stretching is its impact on connective tissue remodeling. Muscles are not the only structures affected by stretching; tendons, ligaments, and fascia all undergo mechanical stress during elongation. With consistent and controlled stretching, these tissues can adapt by reorganizing their collagen fibers, which enhances their tensile strength and elasticity. This remodeling process is crucial for reducing the risk of injury, especially in sports that demand high levels of flexibility and dynamic joint movement.

However, excessive or improper stretching can lead to microtrauma in these connective tissues, resulting in chronic inflammation or instability. This risk is particularly relevant in hypermobile individuals who may already have lax ligaments and are more susceptible to joint dislocations or repetitive strain injuries. For these individuals, the mantra of “more flexibility is better” may backfire. Instead, their focus should be on strengthening the surrounding musculature to stabilize joints rather than aggressively pursuing greater range of motion.

Stretching and the Nervous System: Neurological Adaptation and Tolerance

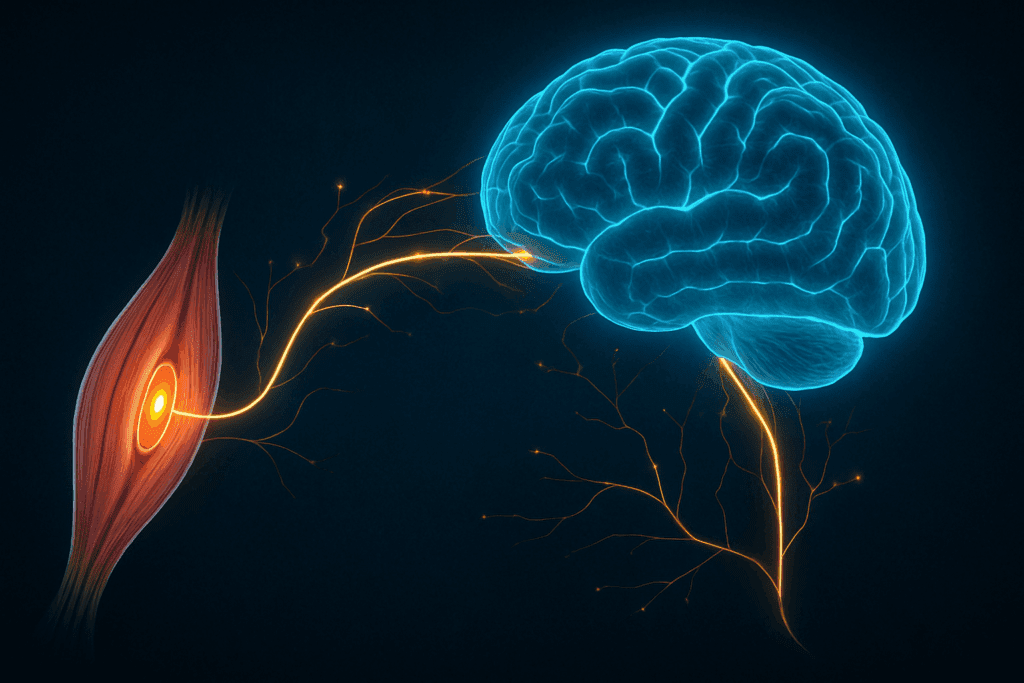

An often-overlooked aspect of stretching is the role of the nervous system in determining perceived flexibility and soreness. Flexibility is not merely a structural property; it is also a neurological phenomenon. When you stretch, mechanoreceptors in your muscles and tendons—such as muscle spindles and Golgi tendon organs—send signals to the spinal cord and brain to assess tension and length. These signals help regulate muscle tone and prevent overstretching that could lead to injury.

Over time, with repeated and consistent stretching, the nervous system becomes more tolerant to the sensation of stretch. This phenomenon is referred to as stretch tolerance. As the nervous system becomes desensitized to the discomfort of stretching, you can achieve greater ranges of motion without experiencing the same level of perceived pain or resistance. This adaptation may explain why early gains in flexibility are often neurological rather than structural.

Importantly, this neurological desensitization also sheds light on why soreness can occur in the early stages of a new stretching routine. The nervous system is essentially being recalibrated, and during this period, muscle soreness from stretching is more likely to occur. Over time, as tolerance improves, both the incidence and intensity of soreness tend to decrease.

Stretching and Proprioception: Enhancing Body Awareness and Stability

Stretching also plays a vital role in improving proprioception—your body’s ability to sense its position in space. Proprioceptive training is crucial for balance, coordination, and joint stability, particularly as we age. Certain types of stretching, such as proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF), actively engage muscle groups while improving range of motion, which can enhance proprioceptive feedback loops in the central nervous system.

This enhancement is especially valuable for injury prevention. Many soft tissue injuries result from poor proprioceptive control rather than a lack of strength. For instance, ankle sprains often occur when an individual misjudges foot placement due to inadequate proprioceptive awareness. Integrating stretching into a broader neuromuscular training program can therefore support both mobility and functional stability.

Stretching for Aging Populations: Mitigating the Decline in Flexibility

As we age, there is a natural decline in muscle elasticity, joint range of motion, and overall mobility. This decline is multifactorial, involving reductions in collagen turnover, increases in connective tissue stiffness, and neurological changes that affect motor control. Stretching becomes an essential intervention for mitigating these changes and preserving functional independence in older adults.

However, older individuals are more prone to delayed recovery and may be more sensitive to soreness from stretching. They must take extra precautions to ensure that stretching routines are safe, progressive, and integrated with strengthening exercises. Overstretching can lead to injury more easily in this demographic, especially if underlying conditions like arthritis or osteoporosis are present. Clinical supervision or guidance from a physical therapist is often recommended.

Additionally, stretching in older populations should prioritize dynamic balance and postural control. Simple movements like seated spinal twists, gentle neck rolls, and dynamic leg swings can improve mobility without placing excessive stress on aging joints. These exercises also help alleviate stiffness from prolonged sitting and improve circulation—critical components of healthy aging.

Why Does Stretching Hurt?

When people ask, “Why does stretching hurt?” the answer can vary depending on context. Mild discomfort during a stretch is usually normal and reflects the tension being placed on muscle and connective tissue. This sensation should be tolerable and subside once the stretch is released. However, sharp or persistent pain is a red flag that the stretch may be too aggressive or that an underlying issue such as a strain, sprain, or nerve impingement is present.

Pain during stretching can also result from chronically tight muscles, previous injury, or musculoskeletal imbalances. For example, individuals with tight hamstrings may experience more pronounced soreness from stretching than those with balanced posterior chain flexibility. Moreover, the presence of inflammation or scar tissue can amplify the discomfort of stretching, as these conditions reduce tissue elasticity and make muscles more reactive to elongation.

Another important factor is the nervous system’s response to stretch. Muscle spindles—sensory receptors within muscle tissue—detect changes in muscle length and send signals to the spinal cord. If the stretch is too rapid or intense, the nervous system may trigger a protective contraction, which can increase discomfort. This reflex, known as the stretch reflex, is a built-in safeguard against overstretching. Understanding this mechanism can help individuals approach stretching more mindfully and avoid pushing beyond the point of productive tension.

The Influence of Hydration, Nutrition, and Sleep on Stretching Outcomes

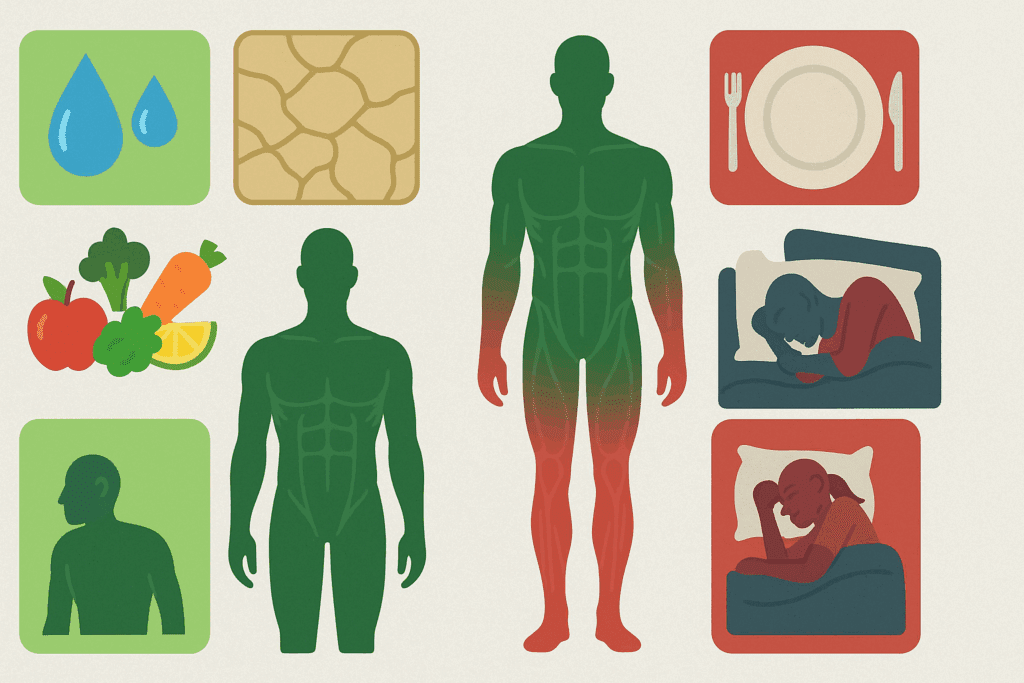

Recovery from stretching-induced soreness is not solely determined by mechanical factors. Systemic health plays a major role, particularly the interrelationship between hydration, nutrition, and sleep. Muscles and fascia are composed largely of water, and dehydration can significantly reduce tissue pliability, increasing the likelihood of soreness and injury during stretching. Staying adequately hydrated supports cellular function, promotes metabolic waste removal, and facilitates the recovery process.

Nutrition also matters. Adequate protein intake supports tissue repair, while micronutrients like magnesium, vitamin D, and omega-3 fatty acids play essential roles in muscle function, inflammation modulation, and collagen synthesis. Sleep, meanwhile, is the foundation of recovery. It is during deep sleep that the body releases growth hormone and performs the bulk of its tissue repair. Stretching while sleep-deprived may not only feel more uncomfortable but also increase the risk of injury.

Stretching as a Tool for Mental and Emotional Wellness

While the physical benefits of stretching are well-documented, its psychological and emotional effects are just beginning to receive the attention they deserve. Stretching can activate the parasympathetic nervous system—the body’s “rest and digest” mode—which promotes relaxation and reduces stress hormones like cortisol. This autonomic shift can have profound effects on mood, emotional regulation, and even pain perception.

In yoga and other mind-body practices, stretching is integrated with breathwork and mindfulness to enhance emotional well-being. This holistic approach not only improves flexibility but also fosters a sense of grounding and inner calm. Individuals who stretch regularly often report improved sleep, reduced anxiety, and a greater sense of embodiment—all of which can contribute to a better quality of life.

These effects may also influence the experience of soreness. Research suggests that individuals with higher perceived stress are more likely to report musculoskeletal pain, including soreness from stretching. Therefore, cultivating a relaxed mental state through mindful stretching may mitigate discomfort and enhance recovery.

Is It Good to Stretch Sore Muscles?

A common dilemma arises when someone is already sore from a previous workout or stretch session: should you stretch while sore? Opinions among fitness professionals vary, but the consensus leans toward gentle, non-aggressive stretching as a useful strategy for managing soreness. When done mindfully, stretching sore muscles can help alleviate tightness, improve circulation, and promote recovery without adding additional strain.

However, the emphasis must be on moderation. Stretching sore muscles should never be painful. Movements should be slow, controlled, and focused on breath awareness to encourage relaxation. Dynamic stretches or active range of motion exercises may be more suitable in these situations than deep static holds. These types of movements allow for mobility without excessive elongation, reducing the risk of exacerbating existing soreness.

It’s also essential to differentiate between soreness and injury. If the discomfort is sharp, localized, or accompanied by swelling or reduced function, it may be a sign of a muscle strain or more serious injury. In such cases, stretching could do more harm than good. Listening to the body and respecting its limits is crucial when deciding whether it’s good to stretch sore muscles or to rest instead.

Can Stretching Make You Sore—or Is It a Sign of Something Else?

It is entirely possible to be sore after stretching, especially if the activity involved unfamiliar or intense movements. But when someone wonders, “Can stretching make you sore?” it’s also important to consider whether other contributing factors may be at play. For example, cumulative fatigue from recent workouts, hydration levels, sleep quality, and overall stress can all influence how the body responds to stretching.

In some cases, soreness from stretching may signal that the person is engaging with tight or underused muscles that are not accustomed to elongation. This type of soreness typically subsides within 24 to 72 hours and is not cause for concern. However, persistent or worsening soreness might point to overstretching or improper technique.

Stretching should never feel like an aggressive pursuit of range of motion. When people ask, “Can you get sore from stretching?” the answer is yes—but with the important caveat that stretching should be approached gradually. Overzealous attempts to force flexibility can result in microtears or even joint instability. The safest path toward improvement is consistent, progressive practice rooted in body awareness.

Can You Overstretch? Recognizing the Risks

One of the lesser-discussed aspects of flexibility training is the risk of overstretching. This occurs when muscles or ligaments are pushed beyond their natural range of motion, potentially leading to strain or damage. While increasing flexibility is a valid goal, it must be balanced with structural integrity. Not all tissues are designed to be lengthened equally, and anatomical differences can dictate personal limits.

Signs of overstretching include sharp pain during or after the stretch, excessive soreness that lasts for days, or a sudden loss of joint stability. When people report being sore after stretching in a way that feels different from exercise-induced soreness, it could be an indicator of overstretching. In these situations, rest and recovery are essential, and consultation with a physical therapist or sports medicine professional may be warranted.

Another concern is that some stretching exercises can be harmful even if performed correctly. For instance, overstretching the hip flexors or lower back in yoga poses like upward-facing dog or deep lunges can place stress on the lumbar spine if not properly aligned. These postures may be safe for some but problematic for others with pre-existing conditions or poor technique. Thus, learning proper alignment and respecting personal anatomical variation is critical in any stretching routine.

Stretching While Sore: How to Do It Safely

Stretching while sore requires a thoughtful and intentional approach. Rather than diving into intense poses, individuals should focus on gentle, rhythmic movements that promote circulation and reduce stiffness. Low-intensity dynamic stretches, such as leg swings, shoulder rolls, and spinal rotations, can be excellent options for reintroducing movement to sore areas without overloading the tissues.

Timing and duration also matter. Short, frequent stretch sessions may be more effective than one long session. Holding a stretch for 15 to 30 seconds while maintaining relaxed breathing can signal to the body that the stretch is safe, reducing the likelihood of a protective muscle contraction. This can help avoid excessive soreness from stretching and support a smoother recovery.

Hydration, nutrition, and sleep are also critical components of the recovery process. Muscles recover more efficiently when the body is well-fueled and rested. Adding techniques such as foam rolling, contrast therapy, or massage can complement stretching and provide additional relief. These modalities may also reduce muscle soreness from stretching by enhancing lymphatic drainage and reducing inflammation.

When to Be Concerned About Soreness After Stretching

Although it’s normal to experience some soreness after stretching, there are times when discomfort may indicate a more serious issue. If pain persists for more than three days, interferes with daily activities, or worsens with movement, it could be a sign of muscle strain, tendon irritation, or even nerve involvement. In these cases, medical evaluation is necessary.

Soreness accompanied by bruising, swelling, or numbness should never be ignored. These symptoms suggest tissue damage or neurological involvement and require professional assessment. Similarly, if soreness consistently follows a specific stretch or exercise, it may be a sign that the technique or alignment needs to be corrected.

Ultimately, the goal of stretching is to support—not hinder—functional movement. While it is common to be sore after stretching, especially when increasing intensity or trying new routines, persistent or severe soreness is not a normal response. Monitoring how the body feels before, during, and after stretching can help individuals make informed decisions about their flexibility training and overall movement health.

How to Stretch Smarter for Long-Term Gains

Effective stretching is not just about increasing flexibility—it’s about promoting sustainable mobility and muscle function. To stretch smarter, individuals should prioritize consistency over intensity. Short daily sessions are more effective and less risky than occasional deep sessions that push the body too far. Incorporating a mix of static, dynamic, and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) stretching can provide a well-rounded approach that addresses both passive flexibility and active range of motion.

Understanding the body’s limitations is also crucial. Not everyone is built to perform the splits or execute deep backbends. Instead of chasing extreme flexibility, aim for balanced mobility across joints and muscle groups. This perspective reduces the risk of injury and minimizes the likelihood of soreness from stretching due to imbalanced training.

Finally, tracking progress and tuning into bodily feedback can help guide adjustments in stretching routines. Keeping a journal of which stretches cause discomfort, when soreness arises, and how the body responds to different techniques can provide valuable insights. This data-driven approach allows individuals to refine their practice and avoid patterns that contribute to excessive soreness or overstretching.

Frequently Asked Questions: Stretching and Muscle Soreness

1. Can you be sore from stretching even if you didn’t exercise beforehand?

Yes, you can be sore from stretching even in the absence of strenuous exercise. This often surprises people, but stretching alone—especially when targeting underused or tight muscle groups—can trigger what’s known as stretching muscle pain. In these cases, the body experiences a low-level muscular stress response similar to that from resistance training, particularly if the stretch is deep or prolonged. While this soreness from stretching may not be as intense as post-workout soreness, it can still affect daily movement and flexibility. For individuals new to flexibility training or returning after a long break, it’s normal to ask, “Can stretching make you sore?”—and the answer is a clear yes, even without prior activity.

2. Why am I sore after stretching when I didn’t feel any discomfort during the session?

Delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS) from stretching can occur without any immediate pain during the stretch itself. Often, people don’t realize they’ve exceeded their tissue tolerance until the inflammation sets in hours later. This delayed reaction is especially common in static stretches held for longer than 30 seconds or performed at end-range. The soreness after stretching might reflect your body’s adaptive response to increased muscle length, not necessarily injury. It’s worth noting that even mild sessions can produce soreness if hydration is low, sleep is inadequate, or muscles are unfamiliar with the motion—contextual factors that explain why stretching while sore can feel more intense the next day.

3. Does stretching sore muscles help recovery, or is rest a better choice?

Whether or not stretching sore muscles helps with recovery depends on how the stretching is performed. Gentle, controlled movements can increase blood flow and reduce inflammation, especially when combined with hydration and active rest. However, if the soreness stems from microtears or overstretching, further elongating the muscles may delay healing. For individuals wondering, “Is it good to stretch sore muscles?” the answer lies in moderation—avoid aggressive poses and instead choose mobility drills that keep joints moving without triggering pain. Over time, you’ll find that certain forms of stretching help sore muscles recover faster, while others may exacerbate the discomfort if done too intensely.

4. Can you over stretch without realizing it, and what are the signs?

Yes, it’s surprisingly easy to over stretch, particularly in yoga, dance, or gymnastics where range of motion is heavily emphasized. You might not feel pain at the time, but symptoms like joint instability, decreased muscle strength, or recurring soreness can surface later. The phrase “can you over stretch” is frequently searched by those who feel great in the moment but experience soreness from stretching that lingers beyond what’s typical. If soreness persists longer than 72 hours or interferes with functional movement, it may be a sign that you’ve exceeded a safe threshold. Repeated overstretching can compromise ligaments over time, leading to reduced joint support and long-term mobility issues.

5. What does stretching do for recovery beyond reducing muscle tightness?

Beyond alleviating tightness, stretching supports recovery by enhancing lymphatic drainage, improving neuromuscular coordination, and reducing postural compensation. When done correctly, stretching sore muscles also improves proprioception—your brain’s ability to map your body in space—which can reduce the likelihood of re-injury. Many athletes use stretching not only to address muscle soreness from stretching itself, but to reset their nervous system after high-stress training. Dynamic stretches in particular can stimulate the parasympathetic nervous system, promoting relaxation and emotional balance. So when people ask, “What does stretching do for recovery?” they’re often unaware of its profound systemic benefits, which go far beyond muscle elasticity.

6. Can stretching help sore muscles after a bad night’s sleep or stressful day? Absolutely—soreness can feel more pronounced when the body is already under stress or sleep-deprived. This is because cortisol, the body’s stress hormone, heightens pain sensitivity and reduces tissue healing capacity. In these cases, gentle stretching can serve as a somatic reset, helping to down-regulate the nervous system while reducing soreness from stretching. For those wondering, “Does stretching help with soreness from stress or fatigue?”—the answer is yes, provided it’s gentle, rhythmic, and mindful. Even light stretches like neck rolls or spinal twists can make a measurable difference in how your body processes tension and recovers from daily strain.

7. Is it normal to be sore after stretching if you’re already very flexible?

Interestingly, yes—it is normal to be sore after stretching even among those who consider themselves flexible. High flexibility does not necessarily mean tissues are resilient or well-hydrated; in fact, hypermobile individuals may be more prone to ligament irritation or nerve compression. In such cases, muscle soreness from stretching could arise from subtle structural instabilities or the activation of compensatory muscles. This demographic is often unaware of their limits because pain may not be felt until long after the stretch occurs. If you’re asking, “Can you get sore from stretching even if you’re flexible?” consider incorporating resistance training to reinforce joint stability alongside your mobility practice.

8. Why does stretching hurt more on one side of the body than the other?

Asymmetrical soreness from stretching is quite common and typically reflects underlying imbalances in strength, mobility, or fascial tension. One side of your body may be more dominant or bear more repetitive strain—think about how you sit, sleep, or carry bags. This asymmetry can lead people to ask, “Why does stretching hurt on one side more than the other?” The discomfort may also point to past injuries or nerve entrapments that affect only one region. To prevent further issues, use unilateral stretches and corrective exercises to address imbalances and reduce the risk of soreness while stretching long-term.

9. Can some stretching exercise be harmful even if performed correctly?

Yes, even technically “correct” stretching can be harmful if the exercise is contraindicated for your body type, injury history, or mobility level. For example, a deep backbend may look flawless but still compress the lumbar spine or strain the hip flexors. This leads to the valid concern that some stretching exercise can be harmful even if performed correctly—especially if tissues are not adequately warmed up or if the movement exceeds your current range of control. The key is personalization: what works for a gymnast may not suit a desk worker with hip immobility. Tailoring your routine is the best way to prevent injury and avoid unnecessary stretching muscle pain.

10. Will stretching help sore muscles over time, or can it make things worse if done daily?

When performed with proper technique and recovery in mind, stretching can absolutely help sore muscles over the long term. However, daily stretching without variation or rest can become counterproductive, especially if tissues are not allowed time to adapt. For those asking, “Will stretching help sore muscles in the long run?” the answer hinges on how well the routine is periodized and whether strength training is included. Without adequate rest or strength reinforcement, daily stretching could lead to accumulated microtrauma or persistent soreness. The solution lies in diversity: alternate stretching intensities, integrate strength work, and take time to rest. That’s how you ensure stretching supports performance instead of hindering it.

Conclusion: Is It Normal to Be Sore After Stretching—and What Should You Do About It?

Yes, it is normal to be sore after stretching, particularly when engaging in new, intense, or prolonged flexibility routines. This soreness often results from microscopic tissue strain, nervous system feedback, or adaptation to novel movement. However, it is equally important to recognize the difference between normal soreness and signs of potential injury.

When done with care, stretching can help sore muscles by increasing blood flow, enhancing mobility, and promoting mental relaxation. But does stretching help muscle soreness or recovery for everyone? The answer depends on the individual, the type of stretching involved, and the context in which it is performed. Stretching sore muscles can be helpful, but only when approached gently and mindfully.

Overstretching, poor technique, or lack of warm-up can all lead to soreness that is counterproductive. That’s why understanding the nuances of stretching muscle pain and recognizing when to rest, when to stretch, and how to adjust based on bodily cues is essential.

In short, if you’re sore after stretching, you’re not alone—and in many cases, it’s a sign that your body is responding to new demands. By listening to your body, stretching with intention, and applying recovery principles, you can use stretching not only to increase flexibility but to support your overall fitness journey with safety and long-term benefits in mind.

Further Reading:

Stretching: Focus on flexibility