Understanding the Aging Brain: Why Cognitive Change Is Not Always Decline

For decades, the prevailing belief in both public discourse and scientific circles was that aging inevitably leads to a decline in mental capacity. Yet this notion—while grounded in some observable truths—has proven to be incomplete. The aging brain does undergo a number of structural and functional changes, but these do not necessarily translate to global cognitive deterioration. In fact, research increasingly shows that what some elders do not lose in brain function may be more remarkable than what they do lose. This emerging insight is reshaping how scientists and healthcare professionals approach late-life cognition and aging.

In biological terms, the brain does show some vulnerability to age-related shifts. There is a gradual loss of synaptic density, a slight reduction in brain volume, and changes in neurotransmitter activity. However, these anatomical and physiological changes vary widely from person to person. Many older adults maintain highly functional, adaptive brains well into their eighties and nineties, suggesting that cognitive resilience can thrive even in the face of age-related neural evolution.

The concept of neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections—has significantly altered how we view the elderly brain. Far from being fixed or inevitably declining, the brain retains a remarkable ability to adapt and rewire itself in response to learning, experience, and even injury. This potential means that individuals can, with the right strategies and lifestyle choices, turn their aging brain around and preserve both memory and cognitive agility. It’s a realization that shifts the narrative from one of decline to one of potential.

This change in perspective has profound implications. It not only challenges the ageist assumptions often baked into our culture but also empowers older adults to become proactive participants in maintaining their mental acuity. Understanding the nuances of cognitive changes in late adulthood is key to dismantling outdated stereotypes and equipping individuals with the tools needed for lifelong brain health.

You may also like: How to Prevent Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease Naturally: Expert-Backed Strategies to Reduce Your Risk Through Lifestyle and Diet

What Science Says About Cognitive Changes in Late Adulthood

To comprehend how to shift an aging brain toward resilience and renewal, we must first examine what actually changes with age. Cognitive changes in late adulthood are complex and multifaceted. While some domains, such as processing speed and working memory, tend to show mild decline, others—particularly those involving crystallized intelligence—remain stable or even improve. Vocabulary, accumulated knowledge, emotional regulation, and social reasoning are often better developed in older adults than in younger individuals.

This divergence between different cognitive faculties explains what some elders do not lose in brain function. They retain, and in many cases refine, their ability to make sound judgments, draw on rich personal histories, and interpret nuanced social dynamics. It’s a testament to the human brain’s depth and its capacity for compensatory mechanisms that enable performance to be maintained despite structural changes.

Importantly, age-related cognitive changes do not occur in a vacuum. Factors such as education level, socioeconomic status, physical health, emotional well-being, and lifestyle habits all influence the trajectory of brain aging. This concept—sometimes referred to as cognitive reserve—suggests that individuals who remain intellectually engaged and socially active tend to fare better in preserving mental function.

Neuroimaging studies add further complexity to our understanding. Functional MRI scans have shown that older adults often activate different brain regions than younger people when solving the same problem, indicating that the elderly brain may adapt through alternate neural pathways. This adaptability provides a crucial foundation for interventions aimed at maintaining or enhancing cognitive function in late adulthood.

Understanding these mechanisms is critical for anyone seeking to turn their aging brain around. Rather than viewing age as a linear descent, we can now see it as a dynamic stage of life in which cognitive vitality is not only possible but highly attainable.

Mental Resilience and the Secrets of the Elderly Brain

Mental resilience refers to the ability to adapt and thrive in the face of adversity, stress, and age-related changes. When applied to the elderly brain, resilience takes on an even more nuanced meaning. It encompasses not just emotional fortitude but also the capacity to maintain cognitive functionality through compensatory strategies, neural flexibility, and lifestyle adaptations.

There is compelling evidence that mental resilience in older adults is not merely the result of genetic luck. Rather, it can be cultivated through purposeful behaviors and environmental enrichment. Social engagement, for instance, plays a crucial role. Older adults who maintain strong social connections tend to exhibit slower rates of cognitive decline, reduced risk of depression, and greater life satisfaction. These benefits appear to be mediated in part by neurochemical mechanisms that enhance synaptic activity and neurogenesis.

Equally vital is the role of meaning and purpose. Studies have found that older adults who have a strong sense of purpose perform better on cognitive tests and exhibit greater resistance to age-related brain changes. This sense of purpose may come from mentoring, volunteering, caregiving, or continuing professional work. These engagements act as natural stimulants for the brain, encouraging mental engagement and emotional investment.

Another often-overlooked aspect is emotional regulation. Unlike younger adults, who may be more reactive to stress, many seniors develop more effective coping mechanisms. This skill enhances resilience by minimizing the cognitive load imposed by chronic stress, which is known to damage the hippocampus—a brain region essential for memory formation. In this context, the elderly brain often demonstrates strengths that younger brains have yet to develop.

Recognizing and amplifying these forms of resilience is central to strategies that aim to turn your aging brain around. It also illustrates what some elders do not lose in brain function: adaptability, emotional depth, and wisdom born from experience.

How to Shift an Aging Brain Toward Cognitive Strength

Shifting the trajectory of the aging brain from decline to vitality is neither fanciful nor reserved for a privileged few. It is a process grounded in neuroscience, psychology, and lifestyle science. The first step in this transformation is understanding that the brain, even in late adulthood, remains plastic—capable of change in response to experience, behavior, and thought patterns.

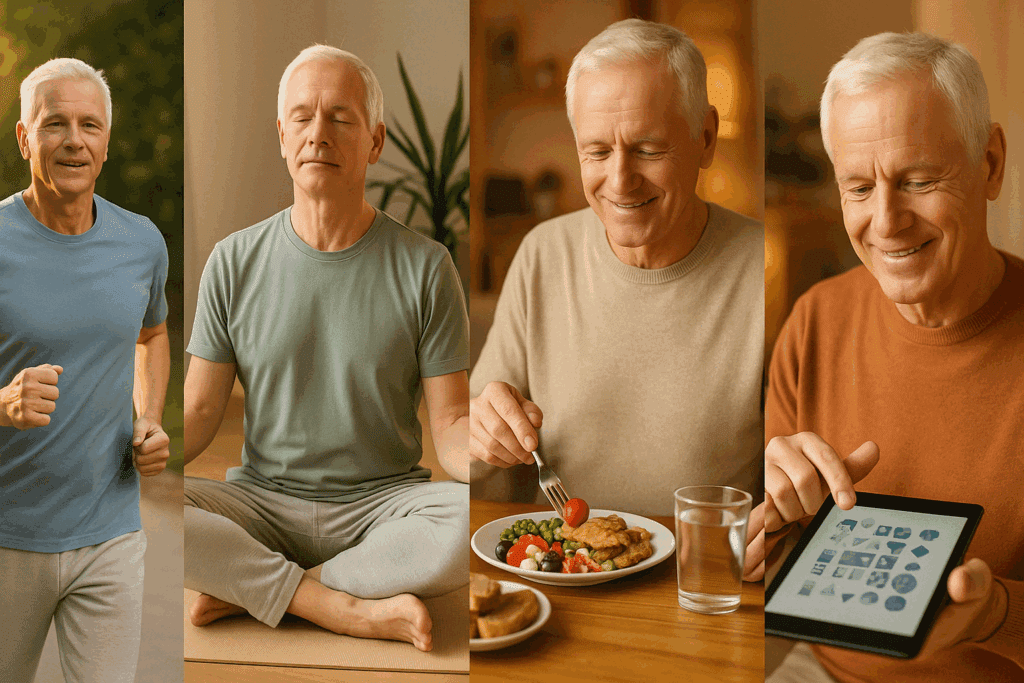

Cognitive training is one avenue with promising results. Brain-training programs that target executive function, attention, and working memory have been shown to improve performance in older adults. Importantly, these improvements often transfer to real-world activities, such as managing finances or navigating new environments. However, the key is consistency. Just as with physical exercise, sporadic cognitive training yields limited results. Sustainable gains come from ongoing mental stimulation that challenges and engages the brain.

Physical exercise cannot be overlooked. Aerobic activity has been shown to increase hippocampal volume and enhance connectivity between brain regions involved in memory and executive function. Resistance training, too, has cognitive benefits, likely through the release of growth factors such as BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor). These findings reinforce the idea that one cannot separate the health of the body from the health of the brain.

Dietary choices also play a critical role. Diets rich in antioxidants, omega-3 fatty acids, and polyphenols—such as the Mediterranean or MIND diet—support brain function by reducing inflammation, improving vascular health, and providing essential nutrients. These nutritional strategies help create an internal environment in which the brain can thrive, making it easier to turn your aging brain around and maintain sharpness into the later decades of life.

Mindfulness and meditation are additional practices that help with how to shift an aging brain. Regular mindfulness practice has been associated with improvements in attention, emotional regulation, and even cortical thickness in brain regions linked to learning and memory. These practices also reduce stress-related cortisol production, thereby protecting the brain from hormone-induced damage over time.

Breaking the Stereotype: What Some Elders Do Not Lose in Brain Function

The idea that cognitive decline is inevitable in old age is a pervasive myth that has long shaped both public policy and personal expectations. Yet the narrative fails to capture the remarkable capacities that many older adults retain, and even expand upon, as they age. The science is now clear: what some elders do not lose in brain function is not only inspiring—it is also instructive.

One key area where aging individuals often excel is pattern recognition and complex problem-solving. These abilities rely heavily on accumulated knowledge and experience, which tend to increase over time. It’s why older professionals in fields ranging from law to medicine to music often reach new heights in their careers well into their sixties and seventies. Far from being a decline, the aging brain in these cases demonstrates enhanced integration of information, nuance, and context.

Emotional intelligence is another domain that tends to remain stable or even improve. Older adults often display greater empathy, patience, and diplomatic skill than their younger counterparts. These capacities contribute to richer social interactions and a higher quality of life, reinforcing the idea that aging does not strip the brain of its most essential human faculties.

Additionally, metacognition—or the ability to reflect on one’s own thinking—often deepens with age. This enhanced self-awareness allows older individuals to make more strategic decisions, compensate for weaknesses, and optimize their strengths. Such insights make a compelling case for redefining what it means to age cognitively, emphasizing growth rather than loss.

By shedding the misconception that aging equates to mental deterioration, we open up a world of possibility for intervention, adaptation, and flourishing. Understanding what some elders do not lose in brain function is not just a scientific insight—it’s a call to action for younger and older generations alike.

Toward a Brain-Healthy Life: Lifestyle Strategies for Mental Longevity

To effectively turn your aging brain around, it is essential to view lifestyle not as a collection of habits but as a holistic framework for mental longevity. Sleep, for instance, is fundamental. Research shows that during deep sleep, the brain clears metabolic waste products, including beta-amyloid, which is associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Poor sleep, by contrast, accelerates cognitive decline and impairs memory consolidation.

Equally important is intellectual curiosity. Lifelong learners who engage in reading, puzzles, second-language acquisition, or music training tend to show higher levels of cognitive performance. These activities stimulate neural circuits and build new connections, counteracting the entropy associated with disuse.

Social relationships also contribute powerfully to mental health. Isolation and loneliness are linked to increased risk of dementia and depression. In contrast, meaningful social interactions enhance emotional resilience and stimulate cognitive function. Community involvement, friendships, and intergenerational bonding offer potent protection against the stresses of aging.

Nutrition, as mentioned earlier, is foundational. Specific nutrients—such as folate, vitamin D, magnesium, and omega-3 fatty acids—support various aspects of brain health, from neurogenesis to neurotransmitter synthesis. Avoiding excessive sugar, saturated fats, and processed foods is equally critical, as these substances promote inflammation and oxidative stress.

By integrating these strategies, older adults can actively shift the trajectory of cognitive aging. It becomes clear that turning your aging brain around is not about reversing time but about maximizing the potential that still exists within the elderly brain.

Rewriting the Narrative: Embracing Brain Growth in Later Life

Perhaps the most transformative shift we can make in our societal understanding of aging is to embrace the concept of lifelong brain growth. The traditional model of cognitive development—peaking in young adulthood and steadily declining thereafter—is giving way to a more nuanced view. Emerging research supports the idea that, with proper care and stimulation, the brain continues to evolve well into old age.

This new paradigm empowers older adults to see themselves not as victims of an inevitable decline, but as active participants in their mental destiny. Through intentional lifestyle choices, strategic cognitive engagement, and a supportive social environment, it is not only possible but probable that many individuals can maintain a high level of mental acuity for the rest of their lives.

It also changes how we design public health interventions, caregiving approaches, and community resources. Recognizing what some elders do not lose in brain function allows for strengths-based strategies that leverage existing capacities rather than fixate on deficits. Such approaches foster dignity, independence, and optimism in the aging population.

In truth, the elderly brain is not a fading relic but a living repository of experience, adaptability, and insight. Understanding how to shift an aging brain away from fear and stagnation—and toward growth and resilience—is among the most important health challenges and opportunities of our time.

Frequently Asked Questions: How to Turn Your Aging Brain Around

1. Can older adults still form new brain connections, or is neuroplasticity limited to youth?

While it’s true that neuroplasticity is more robust during childhood, the ability to form new brain connections does not vanish with age. In fact, emerging research shows that the aging brain maintains a remarkable capacity to adapt to new experiences, particularly when exposed to intellectually stimulating environments. Older adults who learn a new language, pursue hobbies, or engage in strategic games often experience growth in neural connectivity. This plasticity is a cornerstone of how to shift an aging brain toward vitality and resilience. Contrary to old assumptions, what some elders do not lose in brain function is their capacity to learn and innovate when adequately challenged.

2. What role does technology play in maintaining cognitive health in older adults?

Digital technologies offer a growing toolkit to support the elderly brain. Cognitive training apps, online language platforms, and virtual reality programs designed for seniors provide engaging ways to exercise memory and attention. Even video calls and digital social networks can mitigate isolation, which is a key risk factor in cognitive decline. By incorporating digital engagement into daily life, seniors can help turn your aging brain around using tools that were once considered the domain of younger generations. These technologies make it easier to sustain routines that promote long-term brain resilience.

3. How do hormonal changes in late adulthood influence brain function?

Hormonal shifts, such as the decline in estrogen and testosterone, can significantly influence cognitive changes in late adulthood. These hormones affect neurotransmitter activity and blood flow in the brain, both of which are critical for memory and executive function. Postmenopausal women, for example, may experience memory lapses linked to decreased estrogen levels. However, hormone replacement therapies, though controversial, are being studied for their potential to buffer some of these effects. Understanding and addressing these physiological dynamics can support efforts to turn your aging brain around with targeted medical and lifestyle strategies.

4. Can mindset and self-perception influence how the brain ages?

Absolutely. Studies have shown that individuals who maintain a positive outlook on aging often experience slower cognitive decline. This psychological resilience influences both mental and physical health outcomes. When people believe they can grow intellectually, they are more likely to engage in activities that stimulate the brain. This belief system reinforces behaviors that help turn your aging brain around and protect against age-related decline. In this context, what some elders do not lose in brain function may be partly attributed to their mindset.

5. Are there gender differences in how the aging brain responds to lifestyle interventions?

Yes, men and women may experience different benefits from similar interventions. For example, women may respond more positively to social and emotional enrichment activities, while men might benefit more from goal-directed cognitive tasks. These differences are likely rooted in both hormonal and neurological variances. Understanding gender-specific strategies can enhance the effectiveness of programs designed to shift an aging brain toward optimal function. Tailoring interventions can maximize what some elders do not lose in brain function by aligning efforts with individual neurobiological profiles.

6. What role do microglial cells play in cognitive aging?

Microglial cells act as the brain’s immune system and are increasingly recognized as key players in cognitive changes in late adulthood. When functioning properly, they help clear cellular debris and promote neural repair. However, when over-activated—often due to chronic inflammation—they can contribute to neurodegeneration. This imbalance may explain why some individuals experience more pronounced cognitive decline than others. Supporting microglial health through anti-inflammatory diets and stress reduction may help turn your aging brain around by fostering a more favorable neural environment.

7. How do long-term creative pursuits affect the elderly brain?

Engaging in creative activities like painting, writing, or playing music has been linked to higher levels of cognitive flexibility and emotional well-being in older adults. These pursuits activate multiple brain regions simultaneously, enhancing interconnectivity and delaying age-related decline. Creativity also reinforces purpose and self-expression, which are essential elements in maintaining motivation and mental clarity. For those wondering how to shift an aging brain, long-term creative engagement offers a multifaceted, enjoyable, and evidence-based path forward. It’s another domain where what some elders do not lose in brain function is their capacity for imagination and complex problem-solving.

8. How does multilingualism affect cognitive resilience in aging?

Bilingual and multilingual individuals often show higher resistance to age-related cognitive decline. Switching between languages exercises executive function and working memory, two domains often affected in late adulthood. Studies suggest that multilingualism may even delay the onset of dementia symptoms by several years. Encouraging language learning later in life can serve as an effective strategy to turn your aging brain around. It provides a real-world application for how to shift an aging brain toward sustained cognitive health.

9. What are the psychological consequences of ageism on brain health?

Ageism can have serious psychological effects that extend to brain function. Negative stereotypes about aging can become internalized, leading to reduced motivation, withdrawal from mentally stimulating activities, and heightened stress—all of which accelerate cognitive decline. Social messaging that diminishes the capabilities of older adults undermines their willingness to challenge themselves cognitively. Reversing ageist attitudes is essential for creating a culture where turning your aging brain around is viewed as both possible and expected. The elderly brain should be celebrated for its potential, not dismissed due to outdated assumptions.

10. How do intergenerational relationships influence the cognitive trajectory of older adults?

Interacting with younger generations provides emotional nourishment and intellectual stimulation for older adults. These exchanges challenge assumptions, introduce new perspectives, and often involve teaching roles that reinforce cognitive skills. Research shows that intergenerational engagement reduces loneliness and depression, which are risk factors for cognitive decline. Programs that bring seniors and youth together offer a powerful, community-based method to shift an aging brain toward engagement and vitality. They also reinforce the broader truth that what some elders do not lose in brain function is deeply tied to continued connection and contribution.

Conclusion: Turning the Aging Brain Into a Story of Renewal, Not Decline

The aging brain is far more than a symbol of decline—it is a landscape of potential, shaped by years of experience, emotion, and insight. Understanding the science behind cognitive changes in late adulthood reveals a striking truth: much of what some elders do not lose in brain function is preserved, adaptable, and even improvable. With the right mindset and interventions, it is not only possible but deeply empowering to turn your aging brain around.

We now know that the elderly brain retains the capacity for growth, adaptation, and resilience. Strategies that incorporate physical activity, mental engagement, emotional regulation, social connection, and nutrition form the bedrock of how to shift an aging brain toward vitality. This shift isn’t theoretical—it’s being enacted every day by older adults who challenge assumptions and model new possibilities.

Ultimately, the science is not just hopeful—it is actionable. Aging need not be viewed as a decline into obsolescence but rather as a stage rich with opportunity for renewed clarity, purpose, and mental strength. As we collectively rewrite the narrative of aging, we must carry forward the knowledge that cognitive decline is not a foregone conclusion. In its place, we can foster a culture that celebrates the aging brain for what it truly is: resilient, resourceful, and ready for reinvention.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out.

Further Reading:

Cognitive Health and Older Adults

How the Aging Brain Affects Thinking

The aging mind: A complex challenge for research and practice

Disclaimer

The information contained in this article is provided for general informational purposes only and is not intended to serve as medical, legal, or professional advice. While Health11News strives to present accurate, up-to-date, and reliable content, no warranty or guarantee, expressed or implied, is made regarding the completeness, accuracy, or adequacy of the information provided. Readers are strongly advised to seek the guidance of a qualified healthcare provider or other relevant professionals before acting on any information contained in this article. Health11News, its authors, editors, and contributors expressly disclaim any liability for any damages, losses, or consequences arising directly or indirectly from the use, interpretation, or reliance on any information presented herein. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of Health11News.