Understanding the anatomy and physiology of the digestive tract is essential for appreciating how the human body absorbs nutrients, manages waste, and maintains internal balance. Among the most critical components of this system are the small and large intestines. These structures, often depicted in a detailed intestines diagram, are not just passive tubes through which food travels; they are highly specialized organs with distinct yet interdependent roles. Together, they form the core of the intestinal system diagram and play a central part in digestion, absorption, and elimination. This medically accurate guide explores the symbiotic relationship between the small and large intestine, offering readers a comprehensive view of how these organs work together to sustain overall health.

You may also like: How Gut Health Affects Mental Health: Exploring the Gut-Brain Connection Behind Anxiety, Mood, and Depression

The Structural Elegance of the Intestinal Tract

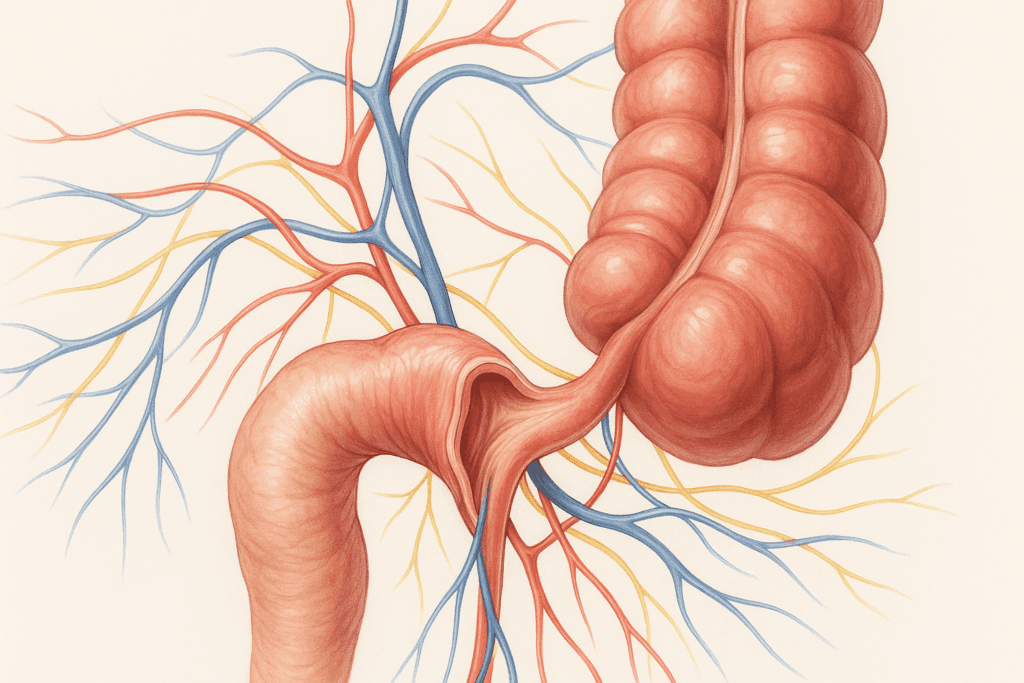

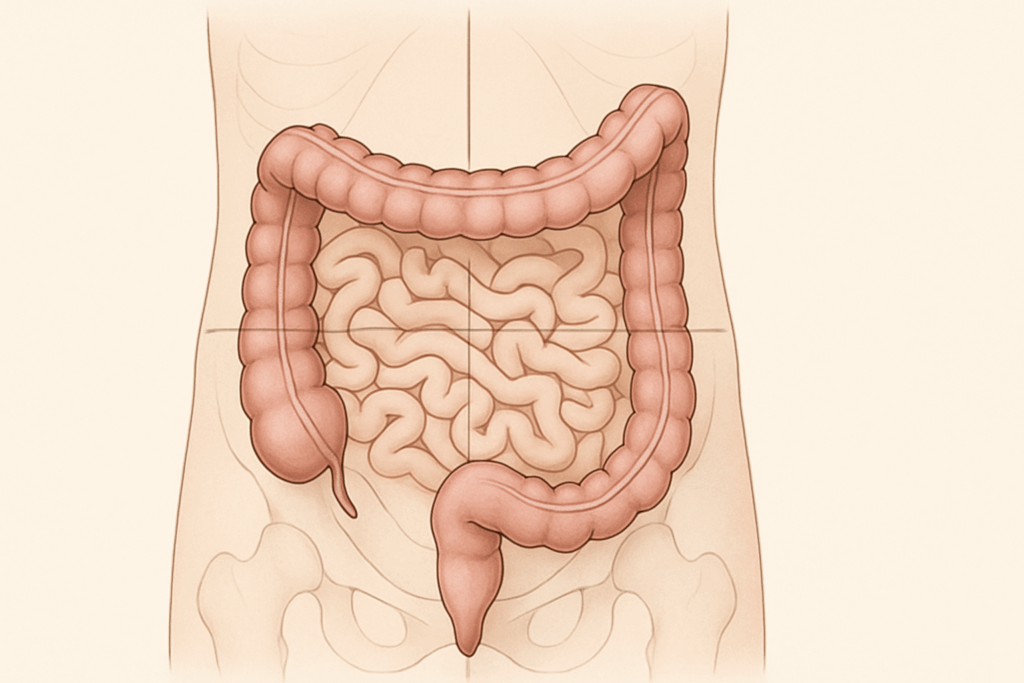

When we consider intestines anatomy, it is helpful to visualize the intestinal tract diagram, which highlights the winding journey that food takes after leaving the stomach. The small intestines, which measure approximately 20 feet in length, begin at the pyloric sphincter and end at the ileocecal valve, where they connect to the large intestine. This structure alone answers the commonly asked question: how long are the intestines? While the large intestine is shorter, measuring roughly 5 to 6 feet, its diameter is significantly greater, which facilitates its specialized role in water absorption and fecal formation.

The small and large intestine are anatomically segmented in a way that supports their distinct yet interconnected functions. The parts of the small intestine include the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum, each tailored for progressive stages of nutrient absorption. Conversely, the large intestine encompasses the cecum, colon (ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid), rectum, and anus. This differentiation is often illustrated in a large intestine diagram or small and large intestine diagram to help clarify their structural complexity. Such diagrams not only show where are the intestines located but also help answer questions like where is your bowel located and what side is your bowel on.

Small Intestine: The Engine of Absorption

The small intestines serve as the primary site of digestion and nutrient absorption. Once chyme enters the duodenum from the stomach, it is mixed with bile and pancreatic enzymes, initiating the breakdown of fats, proteins, and carbohydrates. This first portion of the small bowel begins the intricate chemical processes that prepare nutrients for absorption. As the chyme moves through the jejunum and ileum, the intestinal walls absorb essential vitamins, minerals, and macronutrients into the bloodstream.

Understanding what the small bowel does requires examining the microanatomy of the intestinal lining. Villi and microvilli increase the surface area exponentially, allowing for maximal absorption. This is the essence of what happens in the small intestine: a finely tuned balance between digestive enzymes and absorptive mechanisms. The health of the small intestine is pivotal not only for nutrition but also for immune regulation, as it houses a significant portion of the body’s gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT). Therefore, any dysfunction in the small bowel can lead to systemic consequences, underscoring the importance of recognizing signs of malabsorption and intestinal inflammation.

Large Intestine: The Architect of Elimination

As partially digested material passes through the ileocecal valve, it enters the large intestine, where a markedly different process begins. Here, the focus shifts from absorption of nutrients to the reclamation of water and electrolytes. The large and small bowel work in tandem, but their responsibilities diverge at this point. The large intestine’s primary function is to compact waste and prepare it for excretion. It is also where gut bacteria play a central role in fermenting indigestible fibers, producing short-chain fatty acids that contribute to colonic health.

For those wondering where is poop stored, the answer lies in the rectum, the terminal segment of the large intestine. Prior to this, fecal matter is gradually dehydrated and formed as it moves through the colon. A common question, how long are your bowels, refers to the combined length of both intestines, which together span over 25 feet. This extensive system illustrates the body’s intricate management of waste and fluid balance.

In clinical discussions, the lower intestine is often referenced in relation to colorectal health, emphasizing the importance of screening for disorders such as colorectal cancer and inflammatory bowel disease. The rectum and sigmoid colon are particularly prone to pathological changes, making regular medical surveillance crucial. Medical illustrations such as the bowel diagram or diagram of intestines and colon provide visual clarity on these critical areas, especially when educating patients on where the bowel is situated or where faeces is stored.

Integration Between the Small and Large Intestine

Although the small and large intestines serve different functions, they are not isolated systems. Their integration ensures the efficient progression of digested material, nutrient extraction, water balance, and waste elimination. The transition from the small to the large intestine at the ileocecal valve is not merely anatomical—it represents a physiological checkpoint that regulates the entry of chyme into the colon and prevents bacterial backflow.

This coordination is essential for avoiding conditions such as small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), where microbes from the large intestine migrate backward into the small bowel. The smooth operation of both organs also depends on neurohormonal signaling through the enteric nervous system, often referred to as the “second brain” due to its autonomous control over gastrointestinal motility and secretions. Disruptions in this signaling can result in conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which underscores the delicate balance that defines this segment of human physiology.

Furthermore, when considering how the intestine system diagram is organized, one must account for lymphatic drainage, vascular supply, and innervation—all of which are intricately shared between the small and large intestine. This overlap reflects the body’s emphasis on redundancy and resilience, ensuring that nutrient assimilation and detoxification processes continue seamlessly even under physiological stress.

Anatomical Orientation and Common Clinical Questions

Understanding where are the intestines located or where is your bowel left or right involves appreciating the general layout of abdominal organs. The small intestine is centrally located and framed by the large intestine, which ascends on the right side of the abdomen, crosses transversely, and descends on the left. This positioning answers the frequent query of what side is your bowel on, with the colon primarily anchored along the periphery of the abdominal cavity.

This anatomical orientation is especially useful in clinical diagnostics. Pain in the lower right quadrant, for example, often points to appendicitis, a condition involving the large intestine’s cecum. Conversely, discomfort in the central lower abdomen may suggest issues in the small intestines, such as Crohn’s disease or celiac flare-ups. For healthcare professionals and patients alike, visual tools like the intestine intestine or small and large colon diagrams offer a practical way to visualize internal anatomy and connect symptoms to specific locations.

These illustrations are more than educational aids—they also play a vital role in surgical planning, radiological interpretation, and endoscopic navigation. Whether evaluating how many feet of bowel are viable post-resection or determining where is the bowel situated in relation to other organs, the ability to read an intestinal tract diagram can dramatically influence clinical outcomes.

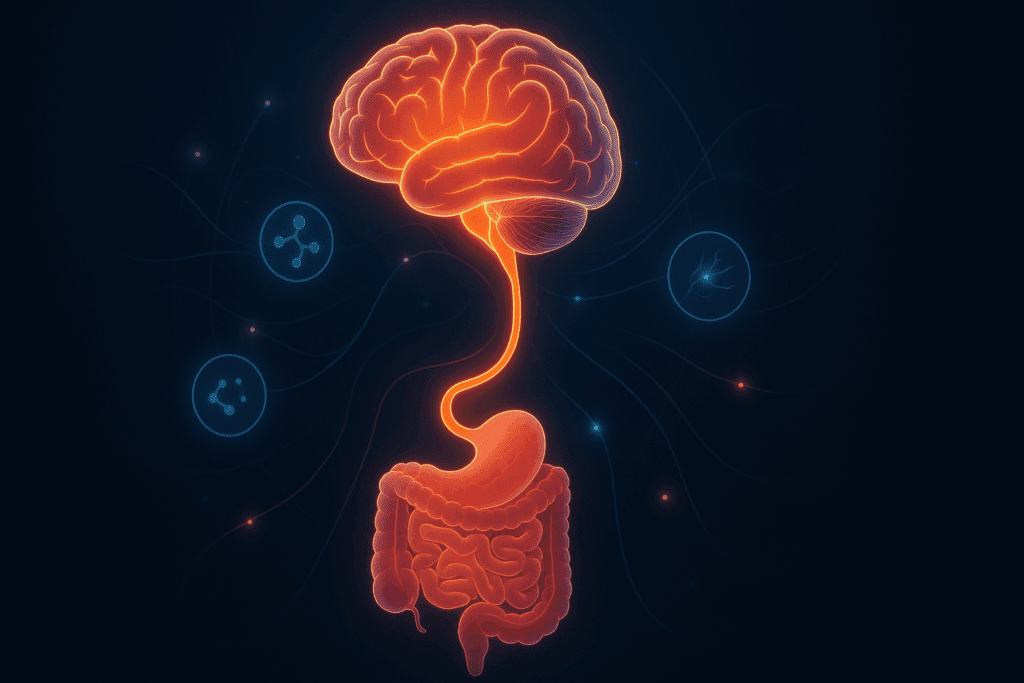

The Gut-Brain Axis: Linking Digestion and Mental Health

One of the most compelling developments in recent medical research is the exploration of the gut-brain axis. This bi-directional communication network connects the gastrointestinal tract with the central nervous system, influencing not just digestion but mood, cognition, and emotional regulation. The health of the small and large intestine directly impacts this axis through microbial composition, inflammatory signaling, and vagal nerve stimulation.

Gut microbiota residing in the colon contribute to the synthesis of neurotransmitters such as serotonin and dopamine, which are essential for emotional well-being. A disturbed intestinal environment—whether due to dysbiosis, chronic inflammation, or malabsorption—can lead to alterations in brain chemistry. This connection adds a psychological dimension to understanding what is function of the small intestine and how the lower intestine affects systemic health beyond digestion.

This growing body of research offers a new perspective on chronic conditions such as depression and anxiety, suggesting that therapeutic interventions targeting the gut—through diet, probiotics, or prebiotics—could enhance mental health. It also reinforces the relevance of digestive anatomy in broader wellness contexts, making the case that where the bowel is located has far-reaching implications for whole-body health.

Developmental and Evolutionary Considerations

The anatomy of the human digestive tract reflects a long evolutionary history. The division of labor between the small and large intestine can be seen as an adaptation to maximize efficiency in nutrient extraction and waste disposal. Early human diets, rich in fibrous plant matter and unprocessed meats, required extended intestinal tracts for adequate digestion, and the current configuration represents a refined balance optimized for omnivorous consumption.

Embryologically, the intestines begin as a single tube that undergoes dramatic elongation and rotation. This process explains the intricate folds and turns visible in any diagram of intestines and colon, and why certain congenital malformations, such as volvulus or intestinal atresia, can disrupt normal gastrointestinal function. Recognizing these developmental origins provides a deeper understanding of both normal and pathological states, helping clinicians anticipate potential issues in both pediatric and adult populations.

Moreover, the intestines’ ability to adapt—through mechanisms like enterocyte regeneration, microbial shifts, and immune recalibration—illustrates a remarkable biological resilience. This adaptability is crucial when portions of the bowel must be removed due to disease or injury. In such cases, questions like how long is the human intestinal tract or how many feet of bowel can be spared without compromising health become central to post-operative care and quality of life assessments.

Nutritional Implications and Practical Health Strategies

The performance of the digestive tract hinges not only on structural integrity but also on dietary inputs. Nutrients that are easily absorbed in the small intestine—such as simple carbohydrates, amino acids, and fatty acids—should be balanced with fibers that feed the microbial ecosystem of the colon. A diet rich in soluble and insoluble fiber supports optimal colonic motility, promotes stool regularity, and aids in the prevention of colorectal diseases.

Understanding how the small and large intestine work together can inform dietary strategies that reduce gastrointestinal distress and improve nutrient utilization. For instance, spacing meals appropriately allows for complete transit through the digestive tract, minimizing bloating and discomfort. Staying hydrated ensures that the large intestine can efficiently reclaim water without leading to hard stools or constipation. Moreover, probiotic-rich foods such as yogurt and fermented vegetables can help maintain microbial diversity, which is essential for both digestion and immune defense.

Patients frequently seek guidance on what foods support bowel health, and while there is no one-size-fits-all answer, tailoring nutrition based on individual tolerance and digestive capacity is key. Those with compromised bowel function—such as individuals with short bowel syndrome—must be especially mindful of meal composition, frequency, and micronutrient supplementation. This practical application of intestinal knowledge reinforces the importance of digestive health literacy for everyday wellness.

Toward a Holistic Understanding of Digestive Health

The interplay between the small and large intestine offers a profound example of physiological synergy. From the detailed insights offered by an intestines diagram to the lived experience of digestive symptoms, understanding this system invites a deeper appreciation for the body’s internal architecture. When asked where is your bowel located or how long are your intestines, the answer is more than anatomical—it is a gateway to understanding how we fuel our cells, protect our immunity, and maintain emotional equilibrium.

Frequently Asked Questions: The Small and Large Intestine

1. What role does the small intestine play in immune system regulation?

While the small intestine is best known for nutrient absorption, it also serves as a frontline defense in the body’s immune system. Specialized immune cells embedded in the intestinal lining help distinguish between harmless food particles and potentially harmful pathogens. These immune cells work closely with gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), a vital part of the body’s immune architecture that lines much of the intestinal tract. Understanding what the small bowel does reveals its role not only in digestion but also in training the immune system, particularly during infancy and early childhood. This immune surveillance function reinforces why the health of the small and large intestine influences not just digestion but systemic inflammation and autoimmune responses.

2. How can posture and physical movement affect the intestines?

Surprisingly, posture has a measurable impact on digestion. Activities such as sitting for long periods or poor pelvic alignment can disrupt normal flow within the lower intestine and increase bloating or constipation. Regular stretching and core-strengthening exercises, such as yoga or walking, can improve intestinal transit by stimulating peristalsis—the wave-like muscle contractions that move food through the intestine intestine. When people ask where is your bowel located, it’s important to note that much of it is packed into the lower abdomen and pelvis, areas highly sensitive to mechanical pressure. Improving body mechanics may be an effective adjunct for those experiencing chronic sluggish bowels.

3. Is there a difference between bowel health and gut health?

Although often used interchangeably, the terms “bowel health” and “gut health” focus on slightly different aspects of the intestinal system diagram. Gut health typically refers to the microbial ecosystem living in the intestines, especially within the large intestine, and how it influences immune function, mood, and metabolism. Bowel health, however, more often centers on mechanical function—how well the intestines process food, absorb water, and eliminate waste. Reviewing a bowel diagram or a large intestine diagram can help illustrate this distinction, showing the areas most impacted by microbial versus motility issues. Maintaining both aspects of health requires a balanced approach to diet, hydration, and stress management.

4. Can the length of your intestines change with age or lifestyle?

While the length of your intestines is mostly determined during early development, certain conditions can cause changes over time. For example, repeated abdominal surgeries may shorten intestinal length, while chronic inflammation in diseases like Crohn’s can lead to resection of parts of the small and large colon. How long are your bowels varies slightly from person to person, typically ranging between 25 to 30 feet in total. As people age, reduced motility and changes in gut microbiota can also impact how effectively these intestines function, even if the actual length remains constant. Exploring how long is the human intestinal tract opens conversations about adaptability and digestive efficiency across the lifespan.

5. Why do people experience discomfort when transitioning from the small to large intestine?

Some individuals experience bloating or cramping near the junction between the small and large intestine, particularly those with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). This transition zone, regulated by the ileocecal valve, can become dysfunctional due to microbial imbalance or inflammation. It is not uncommon for this area to be highly reactive, especially when dealing with poorly digested carbohydrates or fermentable fibers. An intestinal tract diagram may help pinpoint this location when discussing symptoms with a healthcare provider. Recognizing where the bowel is situated, especially in relation to pain, helps patients better advocate for diagnostic imaging or dietary modification.

6. What modern imaging technologies provide the best view of the intestines?

Modern medicine offers several noninvasive ways to visualize the small and large intestine. Capsule endoscopy allows patients to swallow a camera pill that photographs the small intestines in high resolution. Magnetic resonance enterography (MRE) is another technique that creates detailed images without radiation exposure, especially useful for evaluating the parts of the small intestine not easily accessed by standard colonoscopy. Reviewing a comprehensive diagram of intestines and colon alongside such images can enhance patient understanding of diagnoses. For structural and anatomical clarity, nothing beats a high-resolution intestine system diagram paired with expert interpretation.

7. How does diet specifically impact different segments of the bowel?

Diet affects various regions of the bowel in different ways. Simple sugars and proteins are primarily absorbed in the small intestines, while complex fibers reach the large intestine, where fermentation by bacteria generates beneficial short-chain fatty acids. This is why dietary fiber is crucial for large and small bowel synergy. When assessing where faeces is stored or what side is your bowel on in clinical terms, diet becomes a modifiable factor influencing stool form, gas production, and microbial diversity. Recognizing these distinctions can guide individualized dietary strategies based on where in the bowel symptoms are manifesting.

8. How do sex and hormonal fluctuations affect bowel function?

Hormonal shifts, especially involving estrogen and progesterone, significantly influence bowel motility and sensitivity. Many women report changes in stool frequency or consistency around menstruation, pregnancy, or menopause. These fluctuations can affect the lower intestine, altering how efficiently waste is moved and stored. Understanding where is poop stored and what happens in the small intestine versus the colon helps to demystify these common but understudied changes. Hormone-sensitive bowel patterns offer a clear example of how the nervous and endocrine systems interface with digestive anatomy.

9. Can the position of the intestines vary significantly between individuals?

Although the overall layout of the intestines anatomy is consistent, subtle variations exist in how the small and large intestine are positioned within the abdomen. Factors such as body shape, visceral fat distribution, and previous surgeries can shift where the bowel is situated in any given person. This means that answering where is your bowel left or right can differ slightly between individuals. A personalized intestinal tract diagram, generated through imaging studies, may be especially helpful for surgical planning or targeted therapies. These nuances explain why symptoms can present differently in two people with the same underlying condition.

10. What are the future innovations in intestinal health monitoring?

The future of bowel health may involve wearable biosensors, smart pills, and AI-powered diagnostic tools capable of interpreting real-time changes in gut function. Innovations are already emerging that allow noninvasive tracking of pH, pressure, and even microbial composition throughout the small and large intestine. These advancements go beyond a static intestines diagram to offer dynamic, real-world monitoring that empowers earlier diagnosis and personalized care. Whether evaluating how many feet of bowel remain after surgery or assessing subtle shifts in microbiome activity, these tools will redefine how we visualize and manage intestinal health. They also promise to make bowel diagram interpretations more precise, personalized, and proactive than ever before.

Ultimately, digestive health is not an isolated concern but a cornerstone of overall well-being. Whether interpreting a bowel diagram in a clinical setting or simply noticing subtle changes in elimination patterns, an informed perspective empowers both prevention and early intervention. By recognizing the elegance of how the small and large intestine work together, individuals and clinicians alike can promote strategies that support long-term vitality.

In this light, the question of what happens in the small intestine or where is faeces stored becomes more than academic—it becomes a foundation for proactive, informed, and holistic health management that respects the complexity of the human body.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out

Further Reading:

Your Digestive System & How it Works

Digestive Health – Digestive Tract, Accessory Organs, Motility

A Complete Guide to Your Large Intestine – Health

Disclaimer

The information contained in this article is provided for general informational purposes only and is not intended to serve as medical, legal, or professional advice. While Health11News strives to present accurate, up-to-date, and reliable content, no warranty or guarantee, expressed or implied, is made regarding the completeness, accuracy, or adequacy of the information provided. Readers are strongly advised to seek the guidance of a qualified healthcare provider or other relevant professionals before acting on any information contained in this article. Health11News, its authors, editors, and contributors expressly disclaim any liability for any damages, losses, or consequences arising directly or indirectly from the use, interpretation, or reliance on any information presented herein. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of Health11News.