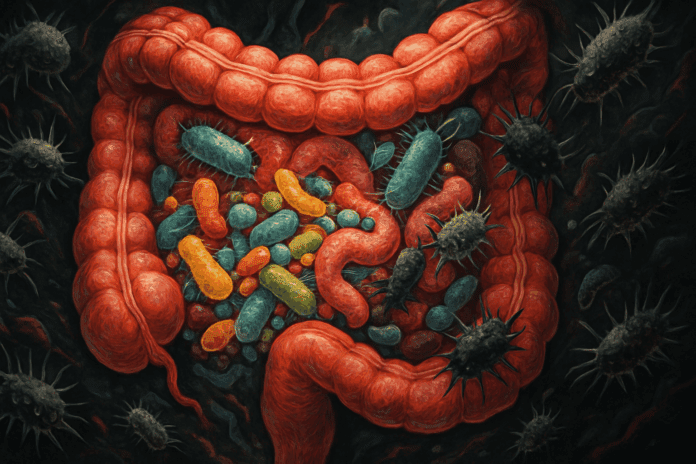

The human gastrointestinal tract is a bustling metropolis of microorganisms, housing trillions of bacteria that form the gut microbiome. Among them are not only the beneficial strains that aid digestion, regulate immune function, and support mental well-being, but also potentially harmful microbes that can disrupt this delicate balance. The presence of these disruptive microbes often leads to a condition known as gut dysbiosis, which refers to an imbalance in the composition of the gut flora. When left unchecked, this microbial misalignment can ripple throughout the body, contributing to a variety of physical and psychological health issues. Understanding how harmful gut bacteria operate, what triggers their proliferation, and how to recognize and resolve gut dysbiosis is essential for maintaining holistic health.

You may also like: How Gut Health Affects Mental Health: Exploring the Gut-Brain Connection Behind Anxiety, Mood, and Depression

The Importance of Microbial Balance in the Gut

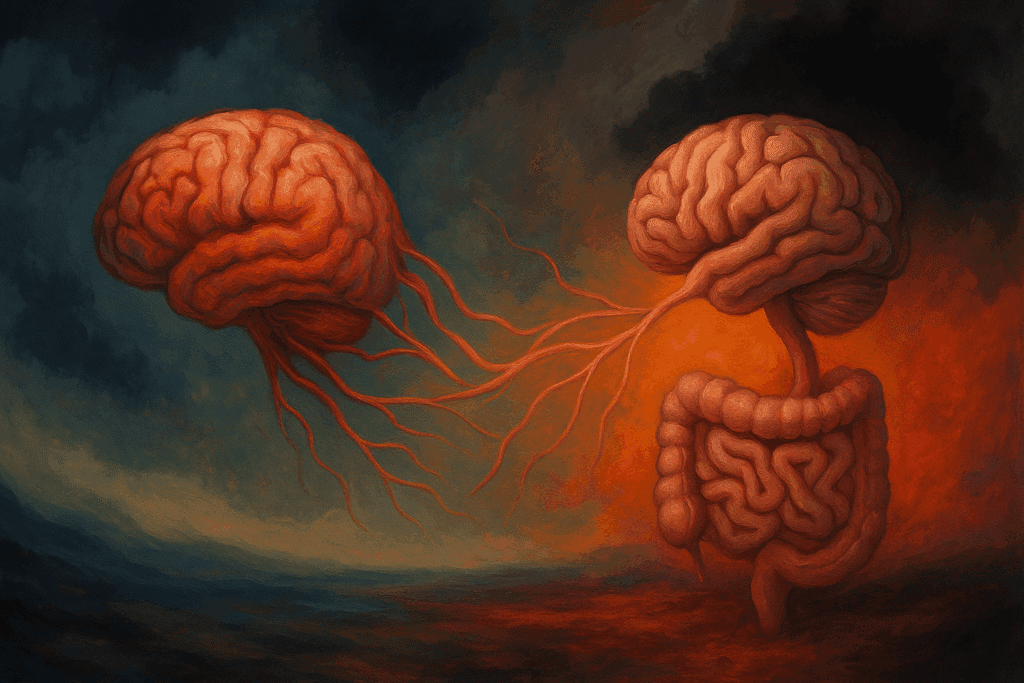

To appreciate the impact of bad gut bacteria, one must first understand the role of good intestinal bacteria. These beneficial microorganisms play a pivotal role in digestion by breaking down complex carbohydrates, synthesizing certain vitamins, and aiding in nutrient absorption. Beyond their digestive duties, they also regulate the immune response, form a protective barrier against pathogens, and even influence neurological function through the gut-brain axis. The concept of the gut as a second brain is not just metaphorical; scientific studies have repeatedly confirmed that gut health and mental well-being are deeply intertwined.

However, the equilibrium between beneficial and harmful gut bacteria is fragile. When disrupted, either by poor diet, excessive antibiotic use, chronic stress, or environmental toxins, the gut’s microbial landscape shifts. This disruption is what is clinically termed gut dysbiosis. It creates a scenario in which harmful bacteria gain dominance, crowding out the beneficial strains and initiating a cascade of detrimental health effects. So, what is bad bacteria in the gut called? While there is no singular name, common culprits include strains like Clostridium difficile, Escherichia coli (certain pathogenic forms), and various species of Salmonella and Campylobacter. These organisms are generally harmless in small numbers, but when allowed to overpopulate, they become a serious threat to health.

Identifying the Hidden Signs of Gut Dysbiosis

One of the challenges of addressing gut dysbiosis is its elusive nature. Symptoms are often nonspecific, overlapping with other health conditions, and may appear far removed from the gastrointestinal tract. Nonetheless, there are several telltale signs that point toward a dysbiotic gut environment. Among the most common gut dysbiosis symptoms are persistent bloating, irregular bowel movements, excessive gas, and abdominal discomfort. However, the effects of an imbalanced microbiome can extend beyond digestion.

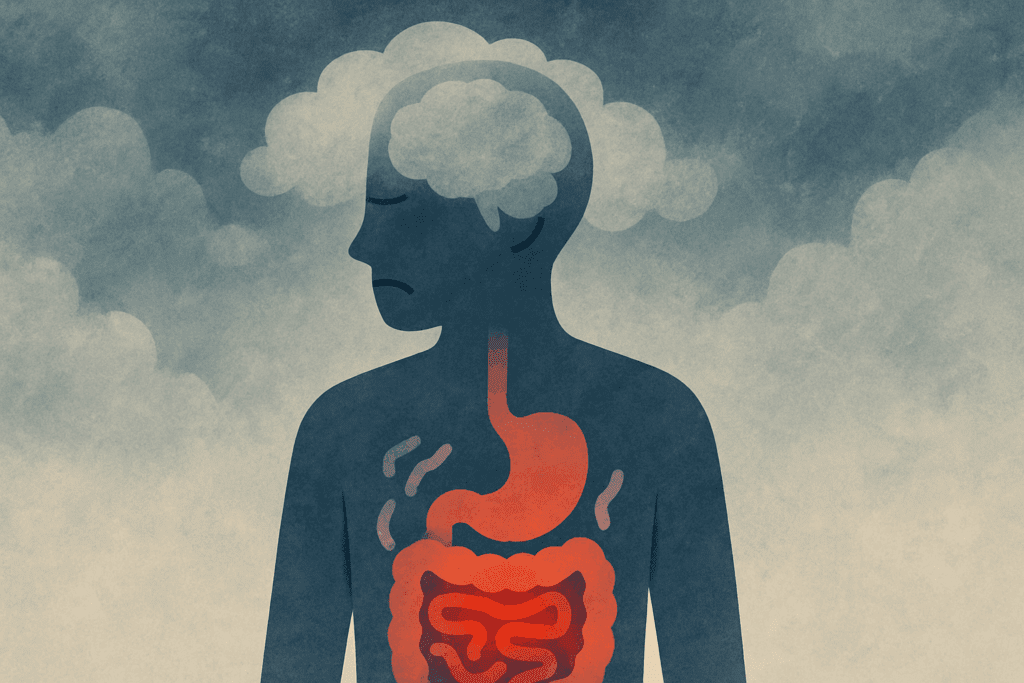

Fatigue, brain fog, mood disturbances such as anxiety and depression, and even skin conditions like eczema and acne have all been associated with microbial imbalance. The gut’s influence on neurotransmitter production, particularly serotonin, explains why psychological symptoms are not uncommon. Bad bacteria in gut symptoms may also include increased food sensitivities, chronic inflammation, and recurring infections due to compromised immune function. Recognizing these patterns is the first step in restoring gut harmony.

How Can the Microbiome Cause Disease if Unbalanced?

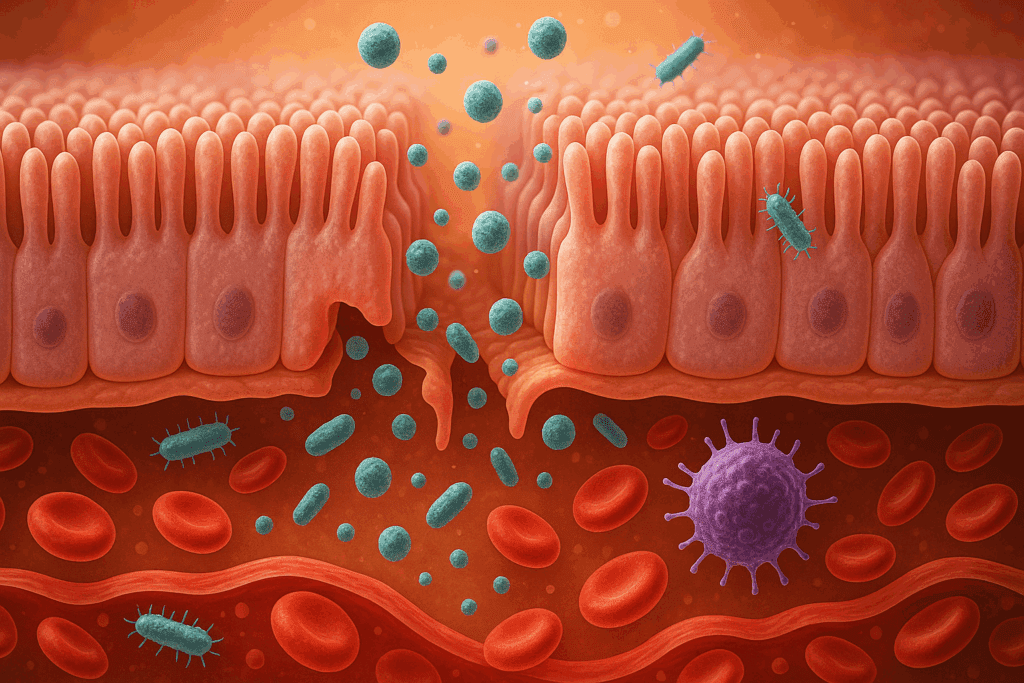

The microbiome acts as a dynamic interface between the body and the external environment. When it is balanced, it fosters resilience, adaptability, and optimal health. But how can the microbiome cause disease if unbalanced? The answer lies in the loss of microbial diversity and the unchecked growth of harmful gut bacteria. These pathogenic organisms produce endotoxins and other inflammatory substances that can damage the intestinal lining, leading to a condition known as increased intestinal permeability, or “leaky gut.”

A leaky gut allows substances such as undigested food particles, toxins, and microbes to enter the bloodstream, prompting an immune response that contributes to systemic inflammation. This chronic inflammation is a known precursor to numerous diseases, including autoimmune conditions, cardiovascular disease, and even certain forms of cancer. Moreover, the presence of gut dysbiosis has been linked to metabolic disorders such as obesity and type 2 diabetes, as well as neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s disease. The mechanisms are complex, but the message is clear: a disrupted microbiome has the potential to influence virtually every system in the body.

The Behavioral and Psychological Toll of Microbial Imbalance

Emerging research has drawn increasingly compelling connections between gut health and mental health. The gut-brain axis, a bidirectional communication network linking the central nervous system and the enteric nervous system, is mediated by neural, hormonal, and immunological pathways. When harmful gut bacteria gain a foothold in the microbiome, they can interfere with these pathways, altering mood, cognition, and emotional regulation.

One key player in this relationship is serotonin, a neurotransmitter of which approximately 90% is produced in the gut. When the microbiome is in dysbiosis, serotonin production may be impaired, leading to increased susceptibility to mood disorders. Additionally, harmful bacteria can trigger the release of cytokines—molecules that mediate inflammation—which in turn can affect brain function and behavior. The resulting symptoms can range from irritability and poor concentration to clinical depression. Addressing gut dysbiosis can therefore be a powerful intervention not just for physical health, but for emotional well-being as well.

How Diet Shapes the Microbiome Landscape

One of the most direct ways to influence the gut microbiome is through diet. The types of foods we consume play a decisive role in determining which microbial species thrive and which diminish. Diets high in refined sugars, artificial sweeteners, and processed foods tend to feed harmful gut bacteria, encouraging their overgrowth and contributing to dysbiosis. Conversely, diets rich in fiber, polyphenols, and fermented foods support the proliferation of good intestinal bacteria.

Prebiotic fibers—found in foods such as garlic, onions, leeks, and bananas—serve as fuel for beneficial microbes. Fermented foods like yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, and kimchi introduce live probiotics into the gut, replenishing and diversifying microbial populations. Importantly, dietary changes can yield significant results within a relatively short time frame, with studies showing shifts in microbiome composition within just days of altering dietary patterns. Strategic dietary interventions thus offer a compelling first step in managing gut dysbiosis symptoms and restoring balance.

Environmental and Lifestyle Factors That Influence Gut Health

While diet is a central pillar of microbiome health, it is not the only one. Lifestyle factors such as stress, sleep, and physical activity also play crucial roles. Chronic stress, for instance, has been shown to alter gut microbiota composition by increasing the abundance of pathogenic bacteria while suppressing beneficial strains. This is mediated in part through the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which regulates the stress response and impacts gut barrier function.

Sleep deprivation similarly disrupts microbial rhythms, leading to reductions in microbial diversity and an increase in inflammation. Exercise, on the other hand, has been associated with improved microbial diversity and enhanced gut barrier integrity. Additionally, environmental exposures—such as the widespread use of antibiotics and sanitizing agents—can deplete microbial diversity, contributing to an ecosystem where bad gut bacteria can flourish. A holistic approach to gut health must therefore account for the broader context of a person’s environment and lifestyle habits.

Effective Clinical Strategies for Diagnosing and Treating Dysbiosis

Accurate diagnosis is critical for effective treatment of gut dysbiosis. While symptoms can suggest microbial imbalance, definitive diagnosis often requires laboratory testing. Comprehensive stool analysis is the most common method, allowing clinicians to evaluate bacterial composition, detect pathogenic organisms, and assess markers of inflammation and digestive function. Breath tests may also be used to detect conditions such as small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), which often overlaps with gut dysbiosis.

Once diagnosed, treatment typically involves a multifaceted approach. In some cases, antimicrobial or antifungal agents—prescribed based on specific microbial overgrowths—may be used to reduce harmful gut bacteria. This is often followed by the introduction of targeted probiotics and prebiotics to rebalance the microbiome. Dietary counseling, stress management, and lifestyle modifications are essential components of any long-term strategy. Addressing the root causes and supporting the regrowth of beneficial flora are the cornerstones of successful microbiome rehabilitation.

The Role of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Postbiotics in Microbial Restoration

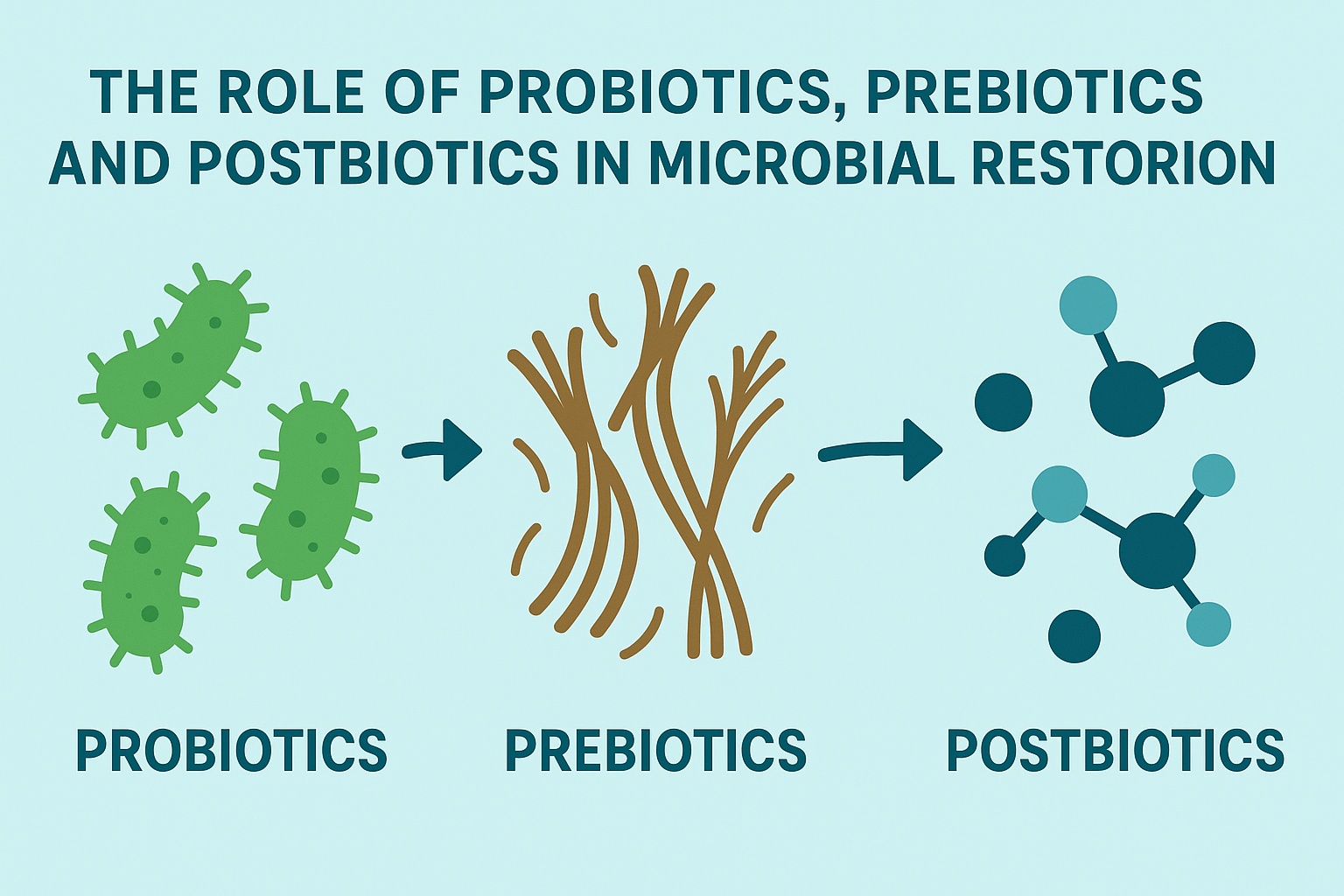

Supplementation with probiotics has become increasingly popular as a means to restore gut balance, but not all probiotics are created equal. The efficacy of a probiotic depends on its strain specificity, dosage, and the unique microbial needs of the individual. Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species are among the most well-researched, with demonstrated benefits for reducing inflammation, improving digestion, and counteracting the effects of harmful gut bacteria.

Prebiotics, on the other hand, are indigestible fibers that selectively nourish beneficial microbes, promoting a favorable gut environment. Postbiotics—metabolic byproducts of microbial activity—are now gaining recognition for their therapeutic potential as well. These include short-chain fatty acids like butyrate, which enhance gut barrier integrity and possess anti-inflammatory properties. An integrated supplementation strategy that includes probiotics, prebiotics, and postbiotics can provide a powerful framework for addressing gut dysbiosis symptoms and preventing recurrence.

Recognizing the Warning Signs of Relapse and Maintaining Long-Term Gut Health

Even after successful treatment, maintaining gut health requires ongoing attention. Relapse into dysbiosis is not uncommon, especially if contributing factors—such as poor diet or chronic stress—remain unaddressed. Recognizing early warning signs such as returning bloating, fatigue, mood swings, or changes in bowel habits can help initiate timely interventions.

Regular consumption of diverse, whole foods, coupled with periodic probiotic and prebiotic supplementation, can help sustain microbial diversity. Stress reduction techniques such as meditation, yoga, and adequate sleep hygiene are also essential. Importantly, individuals should be cautious with unnecessary antibiotic use, as even a single course can significantly alter microbial composition. Preventive strategies rooted in lifestyle and behavioral consistency offer the best chance of maintaining a robust and balanced gut ecosystem.

Frequently Asked Questions: Gut Dysbiosis and Harmful Gut Bacteria

1. Can chronic stress alone trigger gut dysbiosis, even with a healthy diet?

Yes, chronic stress can independently contribute to gut dysbiosis, regardless of diet quality. Sustained stress activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, increasing cortisol levels that directly impact gut barrier function and microbial balance. Elevated cortisol levels reduce the population of good intestinal bacteria and promote the proliferation of bad gut bacteria by altering pH and immune responses in the gut lining. Even in individuals who consume a fiber-rich and whole-foods diet, chronic psychological or physical stress may lead to harmful gut bacteria gaining dominance. Recognizing stress as a standalone risk factor is essential, particularly because many gut dysbiosis symptoms—such as fatigue and mood swings—can overlap with stress-related disorders, making diagnosis more complex.

2. Are there early behavioral signs in children that might signal the presence of gut dysbiosis?

In children, gut dysbiosis symptoms may manifest behaviorally before gastrointestinal signs are noticed. These can include irritability, sleep disturbances, difficulty concentrating, and heightened anxiety or emotional sensitivity. Because the microbiome plays a central role in brain development, an imbalance involving harmful gut bacteria during early life may influence neurodevelopmental outcomes. While pediatric gut health is still an emerging field, studies increasingly suggest that behavioral irregularities might signal microbial imbalance, especially when paired with signs like poor appetite or irregular bowel movements. Monitoring early shifts in behavior may provide important clues about bad bacteria in gut symptoms before chronic digestive issues emerge.

3. How do travel and environmental exposure affect the risk of developing gut dysbiosis?

Frequent travel, especially to regions with differing food hygiene standards or unfamiliar microbial ecosystems, can disrupt the gut microbiome. Exposure to local strains of bad gut bacteria—some of which may be considered pathogenic in one region but commensal in another—can destabilize the microbiome. In such cases, travelers may experience acute gut dysbiosis symptoms such as diarrhea, bloating, or fatigue that linger even after returning home. Environmental contaminants, including chlorinated water and pesticides, can also contribute to the depletion of good intestinal bacteria, increasing vulnerability to harmful strains. While these effects are sometimes temporary, repeated travel without microbiome support can lead to long-term dysbiosis.

4. What is the relationship between autoimmune conditions and bad bacteria in the gut?

Autoimmune diseases are increasingly being linked to gut dysbiosis, particularly when harmful gut bacteria alter immune tolerance. These bacteria can initiate chronic low-grade inflammation and mimic host proteins, a phenomenon known as molecular mimicry, leading the immune system to attack its own tissues. In patients with autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis or Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, microbial imbalances are often observed alongside disease flare-ups. The question “how can the microbiome cause disease if unbalanced?” becomes especially relevant here, as unregulated immune responses are a hallmark of autoimmunity. Correcting dysbiosis through targeted therapies may help modulate disease severity, although treatment should always be coordinated with a specialist.

5. Can exercise routines influence the balance between good and bad gut bacteria?

Yes, both the type and intensity of physical activity can impact gut microbial diversity. Moderate aerobic exercise supports the growth of good intestinal bacteria and can reduce the prevalence of harmful gut bacteria, particularly in sedentary individuals making lifestyle changes. In contrast, overtraining or excessive high-intensity workouts without adequate recovery may promote gut dysbiosis by increasing stress hormone levels and intestinal permeability. Symptoms such as persistent bloating or irregular digestion after rigorous training could be indicators of early gut dysbiosis symptoms. Balanced, consistent exercise routines—paired with proper hydration and sleep—can be a powerful adjunct to dietary strategies for microbiome health.

6. Are there psychological therapies that can aid in restoring microbial balance?

Emerging research supports the role of psychological therapies such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), and gut-directed hypnotherapy in promoting gut health. These interventions reduce the impact of stress on the gut-brain axis and may indirectly reduce the overgrowth of harmful gut bacteria. For individuals whose gut dysbiosis symptoms are closely tied to anxiety or trauma, addressing the psychological root can lead to microbiome improvements. While these therapies do not directly target what is bad bacteria in the gut called, they do alter the internal environment in which such bacteria thrive. Clinical outcomes often improve when psychological and physiological interventions are combined.

7. How can one differentiate between food allergies and gut dysbiosis symptoms?

Food allergies and gut dysbiosis symptoms can overlap but arise from different mechanisms. Allergies involve immune-mediated reactions to specific proteins, often with immediate symptoms like hives, swelling, or anaphylaxis. Gut dysbiosis, on the other hand, may cause food intolerances rather than true allergies, resulting in bloating, fatigue, or brain fog hours after eating. Bad bacteria in gut symptoms often stem from impaired digestion and gut permeability, which allow larger molecules to trigger immune-like responses without a true allergy being present. Comprehensive testing and symptom tracking can help distinguish between the two, enabling more accurate treatment paths and avoiding unnecessary dietary restrictions.

8. Can someone experience gut dysbiosis without having any digestive symptoms?

Yes, it is entirely possible to experience gut dysbiosis without overt digestive symptoms. Many individuals present with extra-intestinal signs such as chronic fatigue, mood disorders, joint pain, or skin issues, which are driven by systemic inflammation initiated by harmful gut bacteria. These cases challenge traditional diagnostic frameworks, especially when bad bacteria in gut symptoms are subtle or mistaken for unrelated conditions. As such, clinicians are beginning to incorporate broader assessments of inflammation and immune activity when evaluating unexplained symptoms. Early screening tools that evaluate microbial metabolites and gut permeability may help identify silent dysbiosis before it progresses to more visible illness.

9. Are there any promising developments in biotechnology for treating gut dysbiosis?

Biotechnology is rapidly expanding the toolkit for managing gut dysbiosis, with advances in precision probiotics, fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), and synthetic microbial ecosystems. Companies are developing strain-specific formulations designed to outcompete harmful gut bacteria without disrupting good intestinal bacteria. Machine learning models now help predict which patients will benefit from particular probiotic strains based on genetic and microbial profiling. FMT, once a fringe treatment, is now gaining FDA approval for recurrent Clostridium difficile infections and may soon be expanded to other dysbiotic conditions. These innovations reflect a growing understanding of how the microbiome can cause disease if unbalanced, and they offer new hope for patients with chronic microbial imbalances.

10. How do antibiotic residues in food contribute to the rise of harmful gut bacteria?

Low-level exposure to antibiotic residues in conventionally raised meat and dairy products can influence gut microbial composition over time. These trace antibiotics may not cause immediate side effects but can reduce microbial diversity and create a favorable environment for the growth of bad gut bacteria. Over time, such exposure may suppress populations of good intestinal bacteria and lead to gradual dysbiosis, especially in individuals with other risk factors such as stress or poor diet. This phenomenon highlights how the microbiome can cause disease if unbalanced—not just through acute infection, but via chronic microbial erosion. Choosing organic or antibiotic-free food sources, when possible, may help mitigate this hidden contributor to gut dysbiosis.

Conclusion: Restoring Balance by Understanding the Risks of Harmful Gut Bacteria

A healthy gut microbiome is not a luxury—it is a foundation for whole-body health. Understanding what bad bacteria in the gut are called, how gut dysbiosis develops, and recognizing bad bacteria in gut symptoms are all essential for early intervention and effective treatment. When the question is posed, “how can the microbiome cause disease if unbalanced?” the answer unfolds across a vast landscape of interconnected systems—from immune dysfunction to mental health disorders. The rise of harmful gut bacteria disrupts not only digestive efficiency but also metabolic, neurological, and immunological harmony.

However, this disruption is not irreversible. By prioritizing dietary diversity, minimizing stress, using evidence-based supplementation, and seeking clinical guidance when necessary, individuals can restore microbial equilibrium. In doing so, they not only resolve immediate symptoms of gut dysbiosis but also build resilience against future health challenges. The road to well-being, it turns out, begins in the gut. With each informed choice—each fiber-rich meal, restful night, and mindful moment—we take a step closer to reclaiming internal balance from the grip of harmful gut bacteria.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out

Further Reading:

Impacts of Gut Bacteria on Human Health and Diseases

Dysbiosis: What It Is, Symptoms, Causes, Treatment & Diet

Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis: Triggers, Consequences

Disclaimer

The information contained in this article is provided for general informational purposes only and is not intended to serve as medical, legal, or professional advice. While Health11News strives to present accurate, up-to-date, and reliable content, no warranty or guarantee, expressed or implied, is made regarding the completeness, accuracy, or adequacy of the information provided. Readers are strongly advised to seek the guidance of a qualified healthcare provider or other relevant professionals before acting on any information contained in this article. Health11News, its authors, editors, and contributors expressly disclaim any liability for any damages, losses, or consequences arising directly or indirectly from the use, interpretation, or reliance on any information presented herein. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of Health11News.