Understanding the Gut-Brain Axis: Where Digestive and Mental Health Intersect

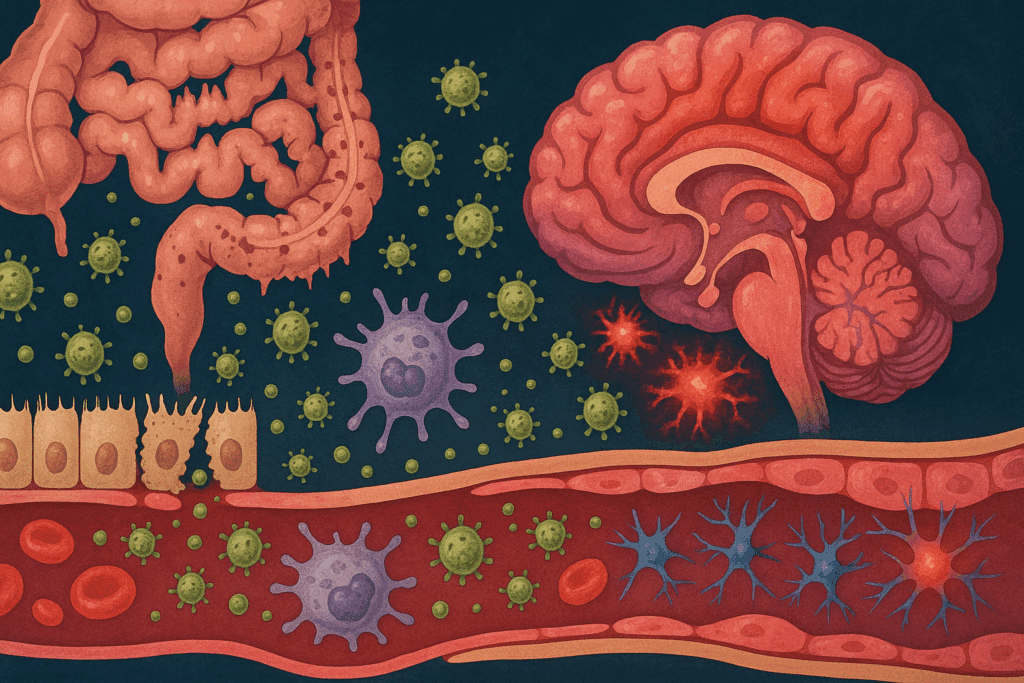

For centuries, the gut was seen as a passive participant in health—responsible solely for digestion, nutrient absorption, and waste elimination. But in recent decades, an explosion of research has reframed the gastrointestinal tract as a dynamic, communicative system with profound influence over neurological function and emotional well-being. Central to this re-evaluation is the concept of the gut-brain axis—a complex, bidirectional communication network linking the central nervous system (CNS) with the enteric nervous system, endocrine signals, immune messengers, and microbial metabolites.

You may also like: How Gut Health Affects Mental Health: Exploring the Gut-Brain Connection Behind Anxiety, Mood, and Depression

This interplay between gut and brain is not merely metaphorical. It manifests in very real, measurable ways, from how gut bacteria influence mood to how inflammation in the intestinal lining can shape cognitive processes. The gut houses approximately 70–80% of the body’s immune cells and produces over 90% of serotonin, a neurotransmitter traditionally associated with mood regulation. This biochemical crosstalk illustrates that disturbances in the gastrointestinal environment can directly affect brain function.

What has increasingly drawn scientific attention is how breaches in intestinal barrier integrity—what is commonly referred to as increased gut permeability—may set off systemic reactions with mental health consequences. Individuals experiencing anxiety, depression, or cognitive fog are now often evaluated through a broader lens that includes gastrointestinal function. As we begin to untangle the mechanistic pathways that connect gut permeability to mental health disorders, it becomes clear that supporting intestinal health is not just a gastrointestinal concern but a neurological and psychiatric one as well.

The Intestinal Barrier: A Gatekeeper of Mental and Physical Health

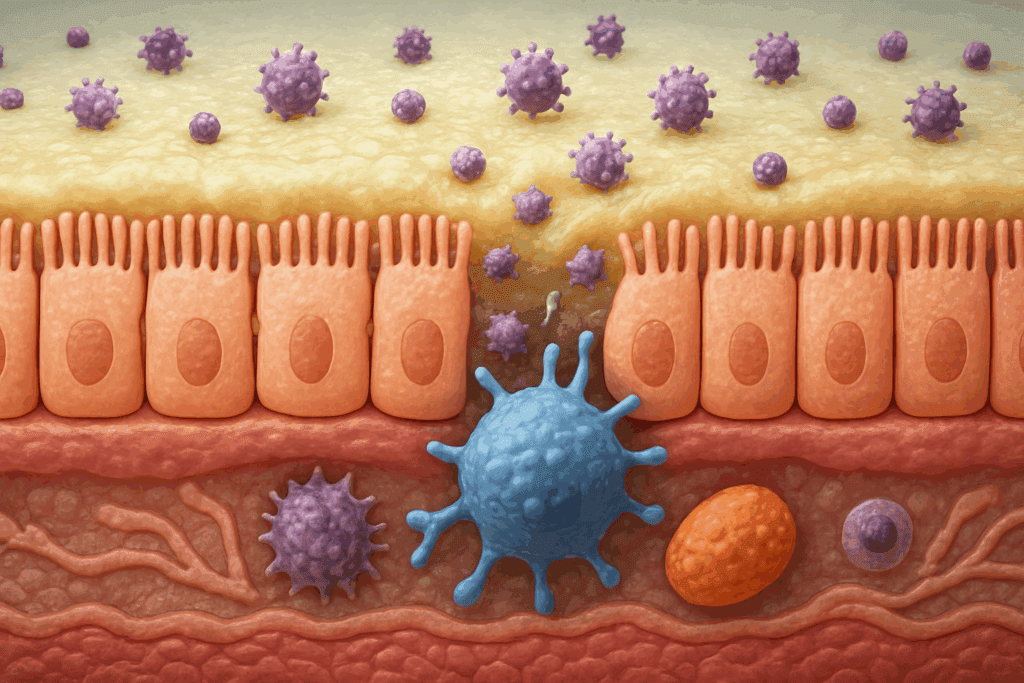

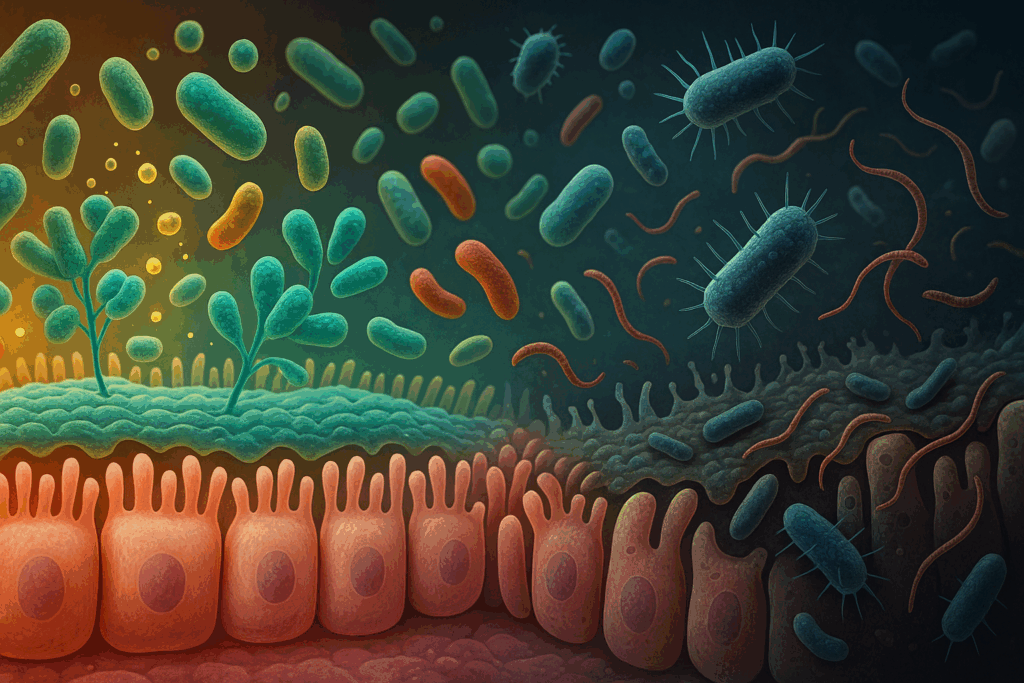

The intestinal lining is often described as a semi-permeable barrier—porous enough to allow essential nutrients to enter the bloodstream, but tight enough to prevent harmful substances from slipping through. It achieves this selective permeability through a sophisticated system of epithelial cells, tight junction proteins, mucosal layers, and immune surveillance mechanisms. Together, these components create a dynamic interface between the external environment and the internal milieu of the body.

Intestinal permeability refers to the degree to which substances can pass through this barrier. Under healthy conditions, tight junctions between epithelial cells prevent unwanted molecules, pathogens, and toxins from entering the bloodstream. However, when these junctions become compromised—a state colloquially referred to as “leaky gut”—they allow foreign particles such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS), undigested food proteins, and microbial fragments to escape into systemic circulation. These incursions can trigger widespread inflammatory responses and neuroimmune activation, both of which are known to affect mood and cognition.

Far from being an isolated gastrointestinal concern, increased intestinal permeability can provoke systemic changes that extend to the brain. Studies in both human and animal models have shown that compromised gut barrier integrity correlates with behavioral changes such as increased anxiety-like behavior, depressive symptoms, and altered stress responses. These findings point to the intestinal barrier as a crucial mediator of mental health outcomes, particularly when viewed in the context of the broader gut-brain axis.

What Causes Increased Gut Permeability? Risk Factors and Modern Lifestyles

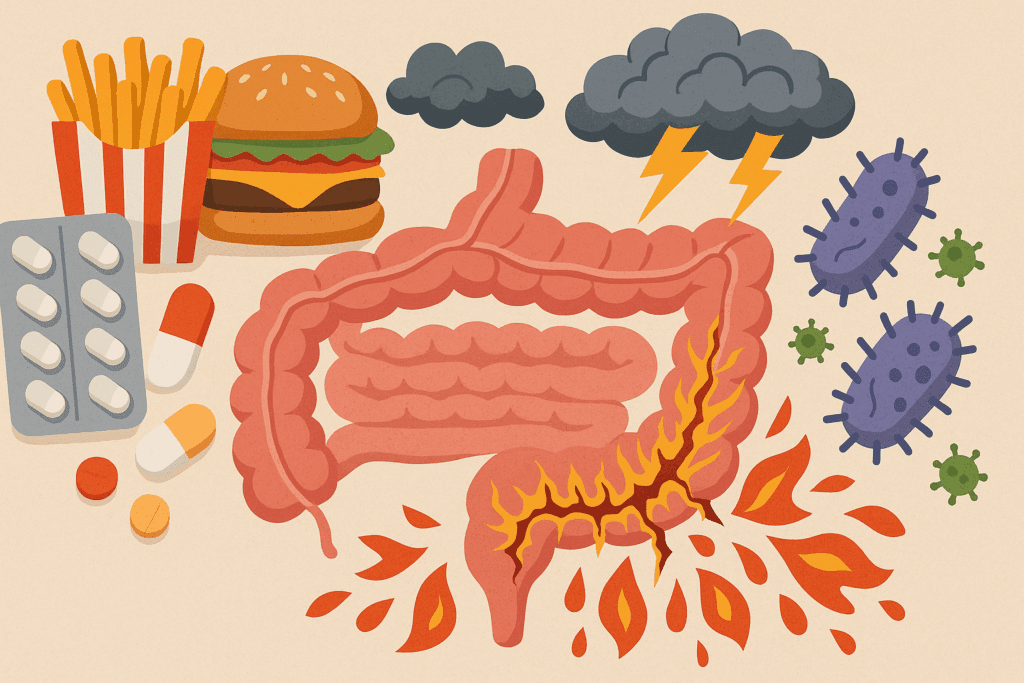

While the intestinal barrier is remarkably resilient, it is not invulnerable. Various environmental and physiological factors can disrupt its integrity and induce increased gut permeability. Chief among these are chronic stress, dietary choices, infections, and the overuse of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and antibiotics.

Stress, especially when chronic or traumatic in nature, has been shown to weaken the tight junctions of the gut lining. Cortisol and other stress hormones can reduce mucosal thickness, suppress protective immune responses, and promote dysbiosis—the disruption of microbial balance in the gut. This dysregulated state is a known contributor to gut permeability and is frequently observed in individuals with mood and anxiety disorders.

Modern diets—particularly those high in refined sugars, processed fats, and food additives—can also compromise gut health. Emulsifiers, artificial sweeteners, and gluten (in susceptible individuals) have all been implicated in the weakening of tight junctions. Meanwhile, fiber-poor diets starve beneficial gut bacteria of the prebiotics they need to produce protective short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, which help maintain mucosal integrity.

Infections, both viral and bacterial, can temporarily increase intestinal permeability, especially when accompanied by gastrointestinal inflammation. Likewise, frequent antibiotic use can eradicate beneficial bacteria that form part of the gut’s first line of defense, allowing opportunistic pathogens to flourish. When these multiple assaults on gut health accumulate, they create a fertile ground for increased permeability—and by extension, a higher risk of neuropsychiatric disturbances.

The Inflammatory Cascade: How Gut Permeability Triggers Brain-Based Symptoms

One of the most significant pathways linking increased gut permeability to mental health dysfunction lies in the body’s inflammatory response. When the intestinal barrier is compromised, foreign antigens and bacterial endotoxins such as LPS translocate into the bloodstream. The immune system, recognizing these molecules as threats, mounts a pro-inflammatory response characterized by the release of cytokines like interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and C-reactive protein (CRP).

These circulating inflammatory markers do not remain confined to the periphery. They can cross the blood-brain barrier, particularly if it too becomes more permeable under chronic inflammatory stress. Once in the central nervous system, these cytokines can disrupt neurotransmitter function, impair synaptic plasticity, and interfere with neurogenesis in the hippocampus—an area critically involved in mood regulation and memory.

Multiple studies have established a clear association between systemic inflammation and mental health disorders. For instance, individuals with major depressive disorder often exhibit elevated levels of IL-6 and CRP. Moreover, treatments that reduce systemic inflammation, whether pharmacological or lifestyle-based, often yield improvements in mood and cognition. These findings suggest that the inflammatory consequences of increased gut permeability are not merely correlational—they are mechanistic contributors to mental health symptoms.

The Role of the Microbiome in Gut and Brain Function

No discussion of gut permeability and mental health would be complete without addressing the human microbiome—the vast ecosystem of microorganisms inhabiting the digestive tract. These microbes play a central role in maintaining the structural and functional integrity of the intestinal barrier. They regulate tight junction expression, produce anti-inflammatory metabolites like SCFAs, and train immune cells to distinguish between harmful and harmless antigens.

Disruptions to the microbiome, whether due to poor diet, antibiotics, or stress, can lead to a state known as dysbiosis. This imbalance favors the growth of pathogenic bacteria that produce metabolites capable of degrading the mucosal lining and loosening tight junctions. In this way, dysbiosis is both a cause and a consequence of increased gut permeability.

Furthermore, microbial metabolites have direct effects on brain chemistry. For example, certain gut bacteria are involved in the synthesis of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), dopamine, and serotonin—all neurotransmitters with key roles in regulating mood, anxiety, and executive function. When the composition of the microbiota shifts away from beneficial strains, these neurochemical pathways can become impaired, contributing to emotional instability and cognitive dysfunction.

Recent clinical trials have begun exploring the use of probiotics and prebiotics to restore microbial balance and, by extension, improve both gut and mental health. Early results are promising, suggesting that microbiome-targeted therapies may one day complement conventional psychiatric treatments, particularly for individuals whose symptoms are linked to gut permeability.

Cognitive and Emotional Impacts of Increased Gut Permeability

The psychological consequences of compromised intestinal integrity are becoming increasingly evident across a wide range of mental health conditions. Depression, anxiety disorders, and even neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative diseases such as autism spectrum disorder and Alzheimer’s have all been associated with increased gut permeability.

In depression, for instance, patients frequently exhibit elevated serum markers of gut-derived inflammation, such as LPS-binding protein and zonulin—a regulator of tight junctions. These findings align with clinical observations of fatigue, brain fog, and emotional numbness that often accompany gastrointestinal complaints in depressive syndromes. Similarly, in individuals with generalized anxiety disorder, studies have documented altered gut microbiota profiles alongside increased markers of immune activation and oxidative stress.

Children on the autism spectrum have long been noted to exhibit higher rates of gastrointestinal disturbances, and recent research has drawn connections between early-life gut permeability and disruptions in social cognition and behavioral regulation. In Alzheimer’s disease, the presence of gut-derived inflammatory molecules has been implicated in the formation of beta-amyloid plaques and tau tangles, hallmarks of cognitive decline.

While causality is still being investigated, the weight of evidence points to gut permeability as a meaningful contributor—not merely a side effect—of cognitive and emotional dysregulation. Addressing the health of the gut barrier may therefore offer new avenues for both prevention and treatment in psychiatry and neurology.

Nutritional Strategies for Supporting Gut Integrity and Mental Clarity

Given the multifaceted role that intestinal permeability plays in shaping mental health, it is not surprising that dietary interventions have emerged as a promising tool for restoring both gut and brain balance. The foundation of any gut-supportive diet is the elimination of inflammatory foods—particularly those high in refined sugars, hydrogenated oils, alcohol, and synthetic additives.

In their place, nutrient-dense, whole foods rich in fiber, polyphenols, and omega-3 fatty acids should take center stage. Prebiotic fibers found in foods like garlic, onions, leeks, and asparagus nourish beneficial gut bacteria, while fermented foods such as yogurt, kefir, and sauerkraut introduce probiotics that support microbial diversity. These nutritional components not only reinforce the structural integrity of the gut lining but also promote the production of mood-stabilizing compounds like SCFAs and tryptophan metabolites.

Collagen-rich foods and supplements containing L-glutamine—an amino acid vital for repairing intestinal cells—have also been shown to improve gut barrier function. Additionally, nutrients like zinc, vitamin D, and omega-3 fatty acids help modulate the immune system and maintain mucosal health, indirectly supporting both gut and neurological function.

Clinical studies have found that such interventions, when tailored to the individual’s unique needs, can significantly reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression, especially when gut dysfunction is a contributing factor. These findings reinforce the notion that mental clarity and emotional resilience are deeply tied to what we eat—and how our digestive system processes those foods.

Lifestyle and Mind-Body Practices That Strengthen the Gut-Brain Connection

Beyond nutrition, a range of lifestyle strategies can help reinforce gut barrier integrity and, in turn, support mental health. One of the most impactful yet underappreciated tools is stress management. Practices such as mindfulness meditation, deep breathing, and yoga have been shown to reduce cortisol levels and downregulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which in turn supports tighter gut junctions and healthier microbial profiles.

Regular physical activity also benefits the gut-brain axis. Exercise has been shown to enhance microbial diversity, reduce systemic inflammation, and stimulate the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which supports cognitive function. Importantly, even moderate levels of movement—such as walking, cycling, or swimming—can yield significant benefits without requiring intense training regimens.

Sleep, often overlooked in discussions of mental health, plays a vital role in gut function as well. Disrupted circadian rhythms can alter microbial populations and reduce the secretion of melatonin, a hormone that modulates both sleep cycles and immune function. Ensuring consistent, restorative sleep can therefore act as a powerful adjunct therapy for both gut and psychological well-being.

When combined, these lifestyle interventions offer a non-pharmacological, integrative path toward healing the gut and, by extension, the mind. They highlight the potential of holistic approaches in supporting both intestinal and mental health.

Frequently Asked Questions: Gut Permeability, Intestinal Health, and Mental Well-Being

1. Can improving gut permeability help individuals with treatment-resistant depression?

Yes, there is emerging evidence that addressing gut permeability may support individuals with depression that doesn’t respond to conventional therapies. One theory suggests that chronic low-grade inflammation—often linked to increased intestinal permeability—can interfere with neurotransmitter function and neuroplasticity, both of which are essential for mood regulation. In treatment-resistant cases, gut-targeted interventions such as anti-inflammatory diets, personalized probiotic regimens, and supplements aimed at reinforcing the gut lining (e.g., glutamine or zinc carnosine) have shown promise. These approaches may not replace antidepressants but can serve as powerful adjuncts, especially when standard treatments plateau. Clinical research is ongoing, but early studies suggest that repairing gut permeability could enhance emotional resilience and responsiveness to psychiatric interventions.

2. How does gut permeability affect the way medications for mental health are absorbed or metabolized?

Increased gut permeability may significantly alter the pharmacokinetics of medications, especially those taken orally. When the gut lining is compromised, it can lead to erratic absorption rates and reduced bioavailability of key psychiatric drugs such as SSRIs or benzodiazepines. This unpredictability may explain why some patients experience inconsistent effects from the same dosage or unexpected side effects. Additionally, a leaky gut may increase systemic exposure to drug-metabolizing bacteria, which can either degrade medications or produce toxic metabolites. For individuals managing mental health conditions, restoring optimal intestinal permeability can create a more stable internal environment for medication absorption and efficacy.

3. Are there specific psychological symptoms that may signal issues with gut permeability?

While psychological symptoms can be influenced by many factors, certain patterns may point toward gut-related contributors. Chronic brain fog, fluctuating energy levels, irritability after meals, and unexplained mood swings are often reported in individuals with suspected gut permeability issues. These symptoms may stem from immune activation or neuroinflammation triggered by the leakage of microbial byproducts into circulation. Though not diagnostic on their own, such signs—especially when accompanied by gastrointestinal discomfort—warrant further investigation into gut health. Addressing gut permeability in these cases often leads to noticeable cognitive and emotional improvements.

4. Can trauma or adverse childhood experiences influence gut permeability in adulthood?

Yes, early-life stress and trauma have been shown to exert long-lasting effects on gut barrier integrity. Through dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, chronic stress can impair the protective mucosal layer, disrupt microbial balance, and compromise tight junction proteins—core components of the intestinal barrier. This dysregulation may persist into adulthood, predisposing individuals to chronic inflammation and increased gut permeability. The psychological toll of trauma may thus be compounded by physiological disruptions that continue to influence mental health decades later. Trauma-informed interventions that include gut healing protocols may therefore offer holistic benefits, addressing both the emotional and biological roots of dysregulation.

5. What role does gut permeability play in neurodivergent conditions like ADHD or autism?

Although research is still developing, increased gut permeability has been implicated in the pathophysiology of neurodevelopmental conditions such as ADHD and autism spectrum disorder (ASD). In ASD, studies have identified higher circulating levels of zonulin—a marker of intestinal permeability—alongside behavioral symptoms and immune dysregulation. Similarly, in children with ADHD, altered gut microbiota and permeability may influence dopamine signaling and executive functioning. While gut permeability is not the root cause of these conditions, it may exacerbate behavioral symptoms by promoting systemic inflammation and neurochemical imbalances. Interventions aimed at restoring gut integrity—like dietary modification, probiotics, and eliminating food sensitivities—may support symptom management in these populations.

6. How does circadian rhythm disruption impact intestinal permeability and mental health?

Circadian misalignment, such as from shift work, jet lag, or chronic insomnia, has been shown to impair gut barrier function. This disruption interferes with the natural cycling of tight junction proteins and digestive secretions, increasing gut permeability and subsequent inflammation. Moreover, microbial populations follow diurnal patterns, and sleep-wake disturbances can trigger dysbiosis, further weakening the intestinal barrier. These changes may lead to altered production of neurotransmitters and stress hormones, creating a feedback loop that worsens both gut and mental health. Prioritizing circadian hygiene—consistent sleep schedules, exposure to natural light, and mindful eating times—can be an overlooked but powerful tool for maintaining gut-brain homeostasis.

7. What is the long-term impact of gut permeability on cognitive decline and aging?

Persistent gut permeability is increasingly being linked to accelerated cognitive aging and a higher risk of neurodegenerative conditions. Chronic exposure to gut-derived inflammatory molecules like LPS may promote oxidative stress in the brain, particularly in regions associated with memory, such as the hippocampus. Over time, this can impair synaptic plasticity and contribute to the accumulation of pathological proteins like amyloid-beta and tau, which are hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease. Furthermore, age-related declines in gut diversity may compound these effects by reducing protective metabolites that help regulate neuroinflammation. By preserving gut barrier integrity through diet, exercise, and microbiome support, individuals may reduce their cognitive risk profile well into older adulthood.

8. Can fasting or time-restricted eating improve gut permeability and mental focus?

Emerging research suggests that time-restricted eating (TRE), a form of intermittent fasting, may positively influence gut barrier function. TRE supports intestinal repair by providing extended periods during which the digestive system is not processing food, allowing tight junctions to recover and inflammation to subside. This fasting window also fosters microbial diversity and enhances the growth of butyrate-producing bacteria, which are essential for gut integrity. Many individuals practicing TRE report improved mental clarity and reduced anxiety—effects that may stem from a reduction in gut permeability and systemic inflammation. However, fasting strategies should be personalized, especially for individuals with a history of eating disorders or metabolic issues.

9. How do hormonal changes, particularly in women, influence gut permeability and emotional health?

Hormonal fluctuations—particularly in estrogen and progesterone—can significantly impact gut permeability and emotional regulation. During the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle or perimenopause, shifts in estrogen levels can disrupt tight junction stability and microbial diversity, increasing susceptibility to gut permeability. This often coincides with mood instability, anxiety, or depressive symptoms, suggesting a synergistic interaction between gut health and hormonal balance. Women with endometriosis, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), or autoimmune thyroid conditions may be especially vulnerable, as all of these are linked to both gut and hormonal dysregulation. Functional medicine approaches that address hormonal and gut health together may yield better outcomes than treating them in isolation.

10. Are there new technologies or biomarkers being developed to assess gut permeability more accurately?

Yes, the field of gut permeability diagnostics is rapidly evolving with the development of non-invasive tools and novel biomarkers. Traditional tests like the lactulose-mannitol test are being supplemented by serum markers such as zonulin, occludin, and LPS-binding protein. Recent innovations include intestinal organoids—miniature models of the gut used in labs to test barrier responses to various stimuli—and wearable biosensors that track real-time changes in gut-derived metabolites. Some startups are even exploring at-home stool microbiome kits that analyze microbial shifts correlated with permeability. These advancements not only enhance our ability to detect gut permeability early but also open the door to highly personalized interventions that align gut repair with mental health optimization.

Conclusion: Strengthening the Gut Barrier to Support Emotional and Cognitive Resilience

The growing body of evidence linking intestinal permeability to mental health represents a paradigm shift in how we understand psychological well-being. No longer can the brain be viewed in isolation from the rest of the body—particularly not from the gut, whose influence reaches far beyond digestion. Increased gut permeability is more than a gastrointestinal issue; it is a systemic concern with profound implications for emotional regulation, cognitive clarity, and overall resilience.

Through its ability to incite systemic inflammation, disrupt neurotransmitter function, and alter microbial populations, gut permeability serves as both a marker and a mechanism of mental health disturbances. But this insight also opens the door to new solutions. By addressing gut health through dietary strategies, stress reduction, targeted supplementation, and lifestyle modification, we can support the healing of the intestinal barrier—and by doing so, promote more stable mood, sharper cognition, and enhanced quality of life.

As the science continues to evolve, one message becomes clear: our mental health is intimately tied to the condition of our gut. Paying attention to intestinal permeability is not just an emerging area of research—it is an essential consideration for anyone seeking to cultivate psychological resilience and lasting well-being.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out

Further Reading:

Intestinal permeability and its significance in psychiatric disorders

Gut-Brain Connection: Microbiome, Gut Barrier, and Environmental Sensors

Disclaimer

The information contained in this article is provided for general informational purposes only and is not intended to serve as medical, legal, or professional advice. While Health11News strives to present accurate, up-to-date, and reliable content, no warranty or guarantee, expressed or implied, is made regarding the completeness, accuracy, or adequacy of the information provided. Readers are strongly advised to seek the guidance of a qualified healthcare provider or other relevant professionals before acting on any information contained in this article. Health11News, its authors, editors, and contributors expressly disclaim any liability for any damages, losses, or consequences arising directly or indirectly from the use, interpretation, or reliance on any information presented herein. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of Health11News.