The field of cognitive medicine has evolved dramatically in recent decades, and at the heart of this evolution is the need for precise, standardized diagnostic criteria to identify and manage conditions that impact mental functioning. Among the most complex and critical of these conditions is dementia—a term that encompasses a variety of syndromes marked by significant cognitive impairment, often affecting memory, reasoning, communication, and everyday function. The release of the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—commonly referred to as the DSM-5—redefined how clinicians approach the classification, diagnosis, and treatment planning for cognitive disorders, including what was traditionally labeled as dementia through the updated DSM-5 Dementia Diagnosis Criteria.

This article delves deeply into how experts apply DSM-5 Dementia Diagnosis Criteria to assess cognitive decline and memory loss, illuminating the changes in diagnostic standards and what they mean for patients, families, and healthcare providers alike. By unpacking the scientific rationale and clinical implications behind the updated dementia diagnosis criteria, we gain valuable insight into the evolving landscape of mental health diagnostics and the nuanced process of identifying neurocognitive disorders.

You may also like: How to Prevent Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease Naturally: Expert-Backed Strategies to Reduce Your Risk Through Lifestyle and Diet

Redefining Dementia: Why the DSM-5 Replaced the Term

One of the most significant shifts introduced by the DSM-5 was the retirement of the term “dementia” as a primary diagnostic label, replacing it with the more precise and encompassing term “major neurocognitive disorder.” This change was not merely semantic—it reflected an effort to destigmatize the condition, more accurately describe the underlying pathology, and acknowledge the range of cognitive impairments that may be present.

The term “dementia” had historically carried connotations of irreversible decline and old age, even though cognitive impairment can affect younger individuals and arise from a wide array of causes, including traumatic brain injury, substance use, infection, and neurodegenerative disease. The DSM-5’s terminology allows for a more inclusive and clinically useful framework. Importantly, the manual still acknowledges that “dementia” remains a commonly used term in clinical and colloquial settings, and it is often listed in parentheses when relevant—for example, “major neurocognitive disorder (dementia)”—to maintain clarity in diagnosis.

This shift reflects the growing understanding that cognitive impairment is not a one-size-fits-all phenomenon. By expanding the diagnostic language, clinicians can more accurately capture the patient’s experience and tailor interventions accordingly. This foundation sets the stage for a deeper exploration of how the DSM-5 defines and classifies dementia and related syndromes under its new criteria.

Understanding the Core Components of DSM-5 Dementia Diagnosis

To diagnose a major neurocognitive disorder under DSM-5 guidelines, clinicians must assess a range of cognitive domains and determine whether impairment is significant enough to interfere with independence in everyday activities. The DSM-5 outlines six key cognitive domains that are evaluated during the diagnostic process: complex attention, executive function, learning and memory, language, perceptual-motor function, and social cognition.

Each of these domains is critical in daily life. For example, impairments in complex attention might manifest as difficulty sustaining focus or being easily distracted, while deficits in executive function could present as poor planning, trouble with decision-making, or inability to shift between tasks. Memory impairment, which is often most closely associated with dementia, involves difficulties with recalling recent events or learning new information. Language deficits may involve problems with naming objects, forming coherent speech, or understanding spoken or written words. Perceptual-motor deficits might show up as trouble recognizing objects, faces, or navigating familiar environments. Finally, social cognition involves understanding and responding appropriately to social cues—something that can become impaired in various neurodegenerative conditions.

A DSM-5 dementia diagnosis, or rather, a diagnosis of major neurocognitive disorder, requires that the deficits in one or more of these areas are not only evident but also represent a significant decline from a previous level of performance. This decline must be observable and measurable, typically through standardized neuropsychological testing and corroborating reports from caregivers, family members, or others familiar with the individual’s functioning. Furthermore, the impairments must interfere with independence in everyday activities, such as managing finances, navigating familiar routes, or remembering appointments.

The Differentiation Between Major and Mild Neurocognitive Disorders

Another pivotal update in the DSM-5’s approach to dementia is the formal recognition of mild neurocognitive disorder (mild NCD), which represents an earlier stage of cognitive decline that does not yet interfere significantly with independence. This category allows for the identification and monitoring of individuals who may be at increased risk for developing major neurocognitive disorder in the future.

In clinical practice, the distinction between mild and major neurocognitive disorder is crucial. While major NCD (DSM-5 dementia equivalent) implies loss of independence, mild NCD indicates that the person retains autonomy in daily life but may experience noticeable inefficiencies in memory, attention, or planning. For example, a person with mild neurocognitive disorder might take longer to complete tasks, rely more heavily on lists or reminders, or show slight declines in performance at work or in social settings. However, these deficits do not yet compromise their ability to function independently.

By including this intermediary diagnosis, the DSM-5 allows for early intervention strategies that may slow cognitive decline. It also provides a framework for differentiating normal aging from pathological changes, offering a more nuanced approach to clinical assessment. In this context, understanding the updated dementia diagnosis criteria gives clinicians a more comprehensive view of cognitive health across a spectrum, rather than a binary categorization of “demented” versus “not demented.”

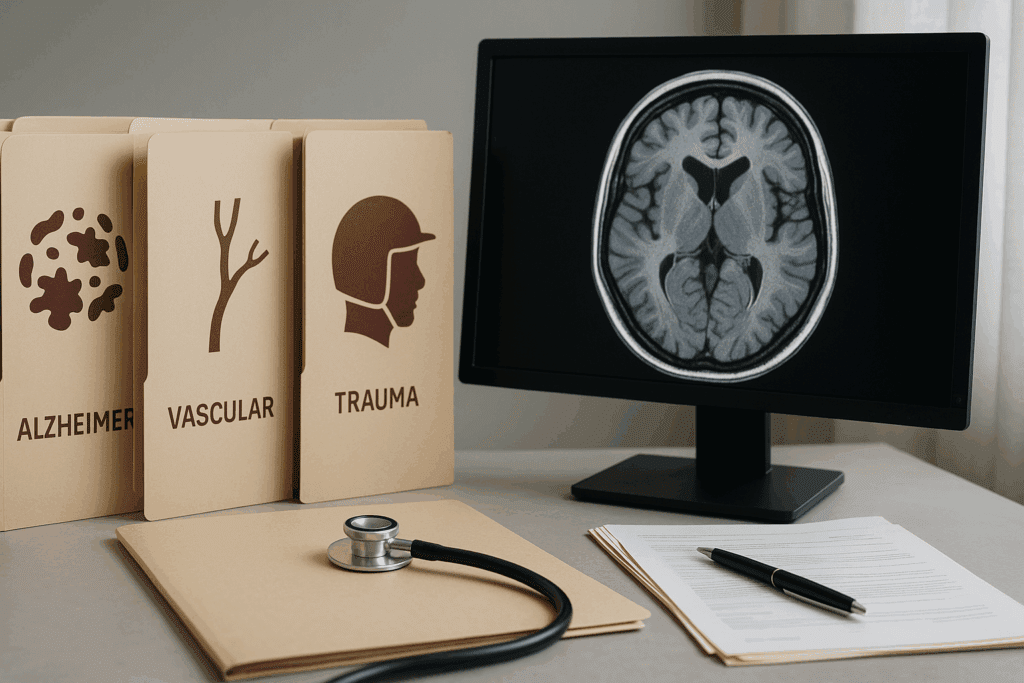

Establishing the Underlying Cause of Cognitive Decline

A core tenet of DSM-5 dementia diagnostic methodology is not only identifying the presence of cognitive impairment but also attributing it to an underlying cause. The manual outlines several possible etiologies of neurocognitive disorders, including but not limited to Alzheimer’s disease, vascular disease, frontotemporal degeneration, Lewy body disease, Parkinson’s disease, traumatic brain injury, HIV infection, and substance or medication use.

This diagnostic step is critical, as treatment and prognosis can vary widely depending on the cause. For example, while Alzheimer’s disease is progressive and currently incurable, neurocognitive disorder due to substance use may improve with cessation of the substance. Similarly, vascular neurocognitive disorder may benefit from interventions targeting cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension or diabetes.

The DSM-5 includes specific diagnostic criteria for each of these subtypes, ensuring that clinicians apply a consistent and evidence-based approach. These criteria often include a combination of clinical history, imaging findings (such as MRI or CT scans), laboratory tests, and behavioral observations. For example, the criteria for Alzheimer’s-type neurocognitive disorder require an insidious onset and gradual progression of impairment, particularly in memory and learning, and a lack of other explanations for the symptoms.

In this way, the DSM-5 dementia framework not only classifies cognitive decline but also guides clinicians toward appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic pathways, emphasizing a biopsychosocial model of care.

Clinical Tools and Cognitive Assessments Aligned with DSM-5 Standards

To accurately apply the dementia diagnosis criteria, clinicians rely on a suite of neuropsychological assessments, clinical interviews, and observational data. Standardized cognitive screening tools—such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), and the Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) exam—are commonly used to detect cognitive deficits across multiple domains.

These tools are designed to measure baseline functioning and detect deviations that may indicate pathology. For example, the MoCA assesses visuospatial skills, naming, memory, attention, language, abstraction, delayed recall, and orientation. Scores below a certain threshold suggest impairment and warrant further evaluation. Importantly, these tools are not used in isolation. They are interpreted alongside comprehensive clinical evaluations, functional assessments, and often, collateral information from caregivers or family members who can report on behavioral changes over time.

Additionally, more detailed neuropsychological batteries may be employed in specialized settings, especially when the diagnosis is unclear or when there is a need to differentiate between competing diagnoses. For instance, testing can help distinguish between depressive pseudodementia and true neurodegenerative disease, or between Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia, which may have overlapping symptoms but different underlying mechanisms.

In this context, the DSM-5 dementia criteria provide a scaffold around which these diagnostic tools are structured, allowing for both consistency and flexibility in clinical application.

The Role of Functional Impairment in Diagnosing Dementia

A defining feature of major neurocognitive disorder, as per DSM-5 standards, is the presence of functional impairment—specifically, the inability to perform daily activities independently. This aspect distinguishes major NCD from mild NCD and underscores the severity of the condition.

Functional impairment can manifest in various ways, depending on the individual’s lifestyle, cultural context, and baseline abilities. In some cases, it may involve difficulty managing medications, preparing meals, driving safely, or maintaining hygiene. In others, the decline may be more subtle, such as failing to keep up with bills, forgetting scheduled events, or becoming increasingly disorganized.

Clinicians often use tools like the Activities of Daily Living (ADL) and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) scales to assess functional status. These scales help quantify the extent of impairment and track changes over time. The DSM-5 dementia diagnostic approach mandates that these impairments be due to cognitive deficits, rather than physical limitations, psychiatric illness, or environmental factors.

Understanding the link between cognitive decline and functional capacity is essential for treatment planning, caregiver support, and decisions regarding long-term care. It also highlights the real-world impact of neurocognitive disorders, moving beyond test scores to evaluate how a person navigates their environment.

Medical and Psychiatric Differentials: Avoiding Misdiagnosis

One of the most challenging aspects of applying the DSM-5 dementia criteria lies in the differential diagnosis. Numerous conditions can mimic the symptoms of cognitive decline, including depression, delirium, normal aging, metabolic disorders, and even sensory impairments like hearing or vision loss. As such, accurate diagnosis requires a comprehensive evaluation that rules out reversible causes of cognitive dysfunction.

For instance, depression in older adults can present with symptoms that closely resemble dementia, including memory complaints, slowed thinking, and diminished concentration—a phenomenon sometimes referred to as “pseudodementia.” Similarly, delirium—a sudden and often reversible disturbance in attention and awareness—must be ruled out before a diagnosis of major neurocognitive disorder can be made. Unlike dementia, delirium typically has an acute onset and fluctuating course, often linked to an identifiable medical trigger such as infection, medication, or dehydration.

Clinicians must also be aware of the effects of polypharmacy, sleep disorders, thyroid dysfunction, and nutritional deficiencies, all of which can contribute to or exacerbate cognitive symptoms. The DSM-5 dementia framework supports this holistic approach by requiring that the cognitive deficits cannot be better explained by another mental disorder or delirium.

This process of exclusion and careful evaluation reinforces the importance of experience, training, and clinical judgment in the diagnostic process, emphasizing that a DSM-5 diagnosis is not made lightly or based on a single encounter.

Why Early and Accurate Diagnosis Matters

Early identification of cognitive decline using DSM-5 dementia criteria offers numerous benefits for patients and their families. It allows for timely intervention, including the management of underlying conditions, initiation of cognitive therapies, and planning for the future. Furthermore, an early diagnosis gives patients an opportunity to participate in decisions about their care, legal matters, and end-of-life planning, while they still have the capacity to do so.

There is also a growing emphasis on lifestyle modifications and pharmacologic treatments that may slow progression or mitigate symptoms. These include exercise, cognitive training, social engagement, and management of cardiovascular risk factors. In Alzheimer’s disease, for example, medications such as cholinesterase inhibitors or NMDA receptor antagonists may offer modest benefits in terms of symptom control and delay of functional decline.

In the broader context of public health, early and accurate diagnosis contributes to epidemiological tracking, resource allocation, and development of targeted interventions. It also supports families by clarifying the source of behavioral changes, reducing caregiver stress, and connecting them with support services and education.

By aligning with the updated dementia diagnosis criteria in the DSM-5, clinicians and healthcare systems can improve diagnostic accuracy, enhance patient outcomes, and promote more compassionate and effective care.

Frequently Asked Questions: Understanding DSM-5 Dementia Diagnosis Criteria and Cognitive Health

1. How does the DSM-5 approach dementia differently for patients under 65?

Although dementia is most commonly associated with older adults, the DSM-5 dementia classification also recognizes early-onset cases, including those that occur before age 65. In younger individuals, diagnosis often involves added complexity, as symptoms may be attributed to stress, depression, or even workplace burnout before cognitive decline is fully recognized. Clinicians using the dementia diagnosis criteria outlined in the DSM-5 must be particularly cautious with early-onset cases, ensuring that neuropsychological testing is extensive and that family or peer input is considered. Moreover, the presentation in younger adults may emphasize changes in executive function or social cognition over memory loss, which is more typical in older populations. This distinction reflects how the DSM-5 dementia framework supports a broader age spectrum than previous editions, thereby encouraging early and accurate diagnosis regardless of age.

2. What role do cultural factors play in applying dementia diagnosis criteria across diverse populations?

Cultural and linguistic factors significantly influence the assessment and interpretation of cognitive symptoms. The DSM-5 dementia diagnosis process must be culturally sensitive, as certain cognitive assessments may be biased toward Western norms of communication, memory tasks, or language structure. For example, a person from a non-English-speaking background might struggle with verbal recall tasks, not due to cognitive impairment but because of language barriers or unfamiliar testing formats. To accommodate this, clinicians are encouraged to use culturally validated testing tools or adapt their approach in line with the patient’s background. The DSM-5 dementia criteria allow for flexibility in evaluation, provided that functional decline is evident and appropriately contextualized. Understanding these nuances is essential to avoid misdiagnosis in multicultural settings.

3. Can individuals with high cognitive reserve still meet DSM-5 dementia criteria?

Yes, individuals with high cognitive reserve—often due to higher education, mentally stimulating careers, or sustained intellectual engagement—may exhibit fewer outward signs of cognitive decline until the condition is quite advanced. These individuals can compensate for early symptoms through learned strategies or mental adaptability, masking the severity of their neurocognitive disorder. However, when their abilities begin to noticeably deteriorate, the DSM-5 dementia framework still applies, as the diagnosis hinges on measurable decline from previous levels of functioning. In these cases, subtle changes in problem-solving, multitasking, or social judgment may emerge before memory deficits become apparent. The inclusion of multiple cognitive domains in the DSM-5 dementia criteria ensures that such individuals are not overlooked simply because their baseline performance was exceptionally high.

4. How are caregivers involved in the DSM-5 diagnostic process for dementia?

Caregiver observations are often pivotal when applying dementia diagnosis criteria, especially when the patient lacks insight into their own cognitive decline—a condition known as anosognosia. The DSM-5 encourages the incorporation of third-party reports to substantiate functional and cognitive changes over time. Caregivers can provide crucial context regarding behavioral shifts, lapses in daily tasks, and emotional responses that might not be captured during clinical evaluations. These insights not only support a more accurate DSM-5 dementia diagnosis but also help distinguish between temporary cognitive fluctuations and progressive decline. Moreover, involving caregivers early fosters a collaborative approach to care planning, support resources, and anticipatory guidance for future needs.

5. Are there emerging technologies that enhance the accuracy of DSM-5 dementia diagnoses?

Yes, advancements in digital cognitive testing, artificial intelligence (AI), and neuroimaging are transforming how clinicians approach dementia diagnosis criteria. Computerized assessments offer standardized, repeatable testing environments that reduce examiner bias and improve longitudinal tracking of cognitive changes. Some platforms now use AI to detect early speech or behavioral patterns associated with cognitive decline. Meanwhile, neuroimaging tools like PET scans and functional MRI can reveal amyloid plaques or metabolic abnormalities that support specific etiological diagnoses under the DSM-5 dementia framework. These technologies are not yet required components of diagnosis, but they provide supplementary data that enhance diagnostic confidence and enable earlier intervention.

6. How do co-occurring psychiatric conditions impact the application of DSM-5 dementia criteria?

The presence of psychiatric disorders—such as depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia—can complicate the interpretation of cognitive symptoms. Depression, in particular, may mimic dementia symptoms by impairing attention, memory, and processing speed, a phenomenon sometimes called “pseudodementia.” DSM-5 dementia criteria specifically require that cognitive deficits are not better explained by another mental disorder. This mandates thorough differential diagnosis, often involving trial treatment for psychiatric symptoms before confirming a neurocognitive disorder. Furthermore, long-term psychiatric conditions may themselves increase the risk of developing major neurocognitive disorders, underscoring the need for vigilant monitoring in this population. When properly applied, the DSM-5 framework allows clinicians to disentangle overlapping symptom profiles to ensure accurate diagnosis.

7. In what ways does the DSM-5 support early intervention for cognitive decline?

One of the most valuable contributions of the DSM-5 dementia framework is the introduction of mild neurocognitive disorder, which identifies individuals at risk before their condition becomes debilitating. This allows for the implementation of early interventions such as cognitive training, medication trials, lifestyle modifications, or occupational adjustments. Early diagnosis also empowers patients to make proactive decisions regarding future care, finances, and legal planning while they still retain decision-making capacity. In public health contexts, applying the dementia diagnosis criteria at an earlier stage may also improve screening protocols and resource allocation for aging populations. The DSM-5’s emphasis on detecting preclinical changes reflects a paradigm shift toward prevention and delay rather than reactive care.

8. How does the DSM-5 classification influence legal and financial planning for patients with cognitive decline?

A formal DSM-5 dementia diagnosis often becomes a trigger point for initiating legal, financial, and caregiving arrangements. For example, once a diagnosis is made, it may affect the patient’s ability to manage contracts, consent to medical procedures, or retain financial autonomy. Families and legal advisors may use the documented diagnosis to establish power of attorney, guardianship, or trusts. The DSM-5’s structured diagnostic language helps clarify the severity of impairment, which is often essential in court settings or when advocating for benefits and services. Moreover, clear alignment with dementia diagnosis criteria ensures that any decisions are backed by medical authority, thereby reducing potential disputes over competency and consent.

9. What are some overlooked signs that might still meet DSM-5 dementia thresholds?

While memory loss is commonly associated with dementia, the DSM-5 highlights other cognitive domains that can reveal impairment. A person may exhibit early changes in judgment, such as falling for scams or making unsafe decisions, without showing noticeable forgetfulness. Likewise, subtle shifts in personality, loss of empathy, or inappropriate social behavior can suggest deterioration in social cognition or executive function. In these cases, traditional memory tests may be insufficient, and broader neuropsychological evaluation is needed to meet the DSM-5 dementia criteria. Recognizing these less obvious signs is essential to capturing atypical presentations and ensuring patients receive appropriate care.

10. How might future revisions to the DSM affect dementia diagnosis criteria?

As research into neurodegenerative diseases accelerates, future versions of the DSM may expand or refine how dementia is classified and diagnosed. Biomarkers, for instance, are becoming increasingly central to research definitions of conditions like Alzheimer’s disease, and it is likely that future iterations of the DSM will incorporate these tools more formally into diagnostic frameworks. Additionally, machine learning algorithms and wearable health technologies may play a larger role in identifying early patterns of decline, especially in remote or underserved populations. These innovations could lead to more dynamic versions of the DSM-5 dementia structure, blending clinical observation with real-time data analytics. As the science evolves, so too will the criteria—always with the goal of enhancing accuracy, empathy, and patient-centered care.

Conclusion: Embracing the DSM-5 Framework for a Better Understanding of Cognitive Decline

In an age when cognitive health is becoming an increasingly vital concern for aging populations around the world, understanding how the DSM-5 dementia criteria shape diagnosis is more important than ever. This comprehensive and nuanced framework allows for a more accurate, compassionate, and scientifically grounded approach to identifying cognitive impairment. By replacing the outdated and stigmatized term “dementia” with the broader and clinically precise category of major neurocognitive disorder, the DSM-5 opens new avenues for early recognition, effective treatment, and personalized care planning.

At its core, the DSM-5 dementia framework emphasizes the importance of measuring functional impact, ruling out reversible causes, and establishing the likely etiology of cognitive decline. These elements guide clinicians not only in diagnosing the condition but also in supporting patients and families through what is often a life-altering process. Moreover, the framework’s inclusion of mild neurocognitive disorder encourages earlier intervention and preventive strategies, helping individuals maintain autonomy and quality of life for as long as possible.

For clinicians, caregivers, and policymakers alike, a firm grasp of DSM-5 dementia diagnosis criteria is foundational to delivering effective, humane, and evidence-based care. As our understanding of neurocognitive disorders continues to evolve, the DSM-5 remains a touchstone for clinical excellence and a guiding document in the pursuit of mental health and cognitive well-being.

Further Reading:

Dementia and Cognitive Impairment: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Neurocognitive disorders in DSM 5 project — Personal comments