Depression is often recognized for its emotional toll—persistent sadness, low motivation, and feelings of hopelessness. Yet, beyond the emotional experience, depression is also deeply entwined with how the brain processes, stores, and retrieves information. A growing body of evidence reveals that mood disorders are not merely psychological in nature—they manifest cognitively, with profound implications for memory, concentration, processing speed, and executive function. This cognitive shadow of depression is increasingly acknowledged by neuroscientists and clinicians alike, offering new avenues for both understanding and managing the condition.

The interplay between depression and cognitive impairment is more than a side effect; it is a core feature for many individuals, often lingering even after mood symptoms have improved. The brain’s ability to think clearly, maintain attention, and recall information becomes compromised in ways that are measurable and, for many, deeply disruptive to daily life. Exploring the connections between depression and thinking reveals a complex landscape of neurochemical changes, disrupted brain networks, and psychological strain—all of which converge to impair cognition in subtle and sometimes surprising ways.

As we deepen our understanding of how depression shapes the brain’s capacity to think and reason, we uncover a critical but often overlooked dimension of mental health. Cognitive depression, as it is increasingly termed in clinical literature, challenges the traditional view of depression as solely emotional. Instead, it opens the door to more comprehensive treatment approaches that address not only mood but also the cognitive symptoms of depression that silently erode quality of life.

You may also like: How to Prevent Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease Naturally: Expert-Backed Strategies to Reduce Your Risk Through Lifestyle and Diet

The Overlooked Dimension of Depression: Beyond Emotions to Cognitive Decline

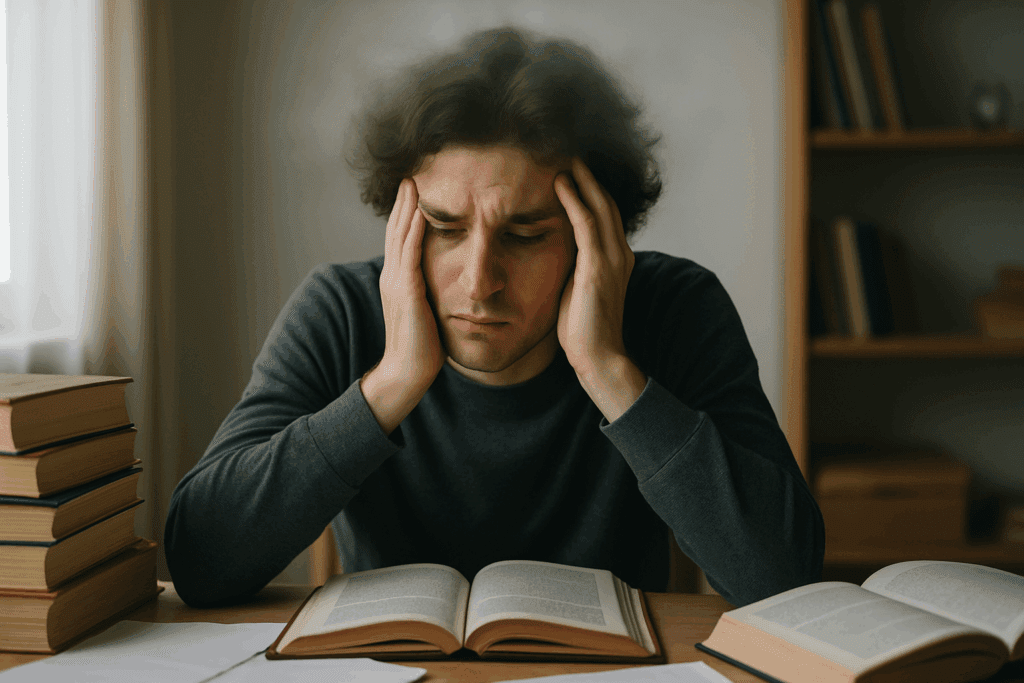

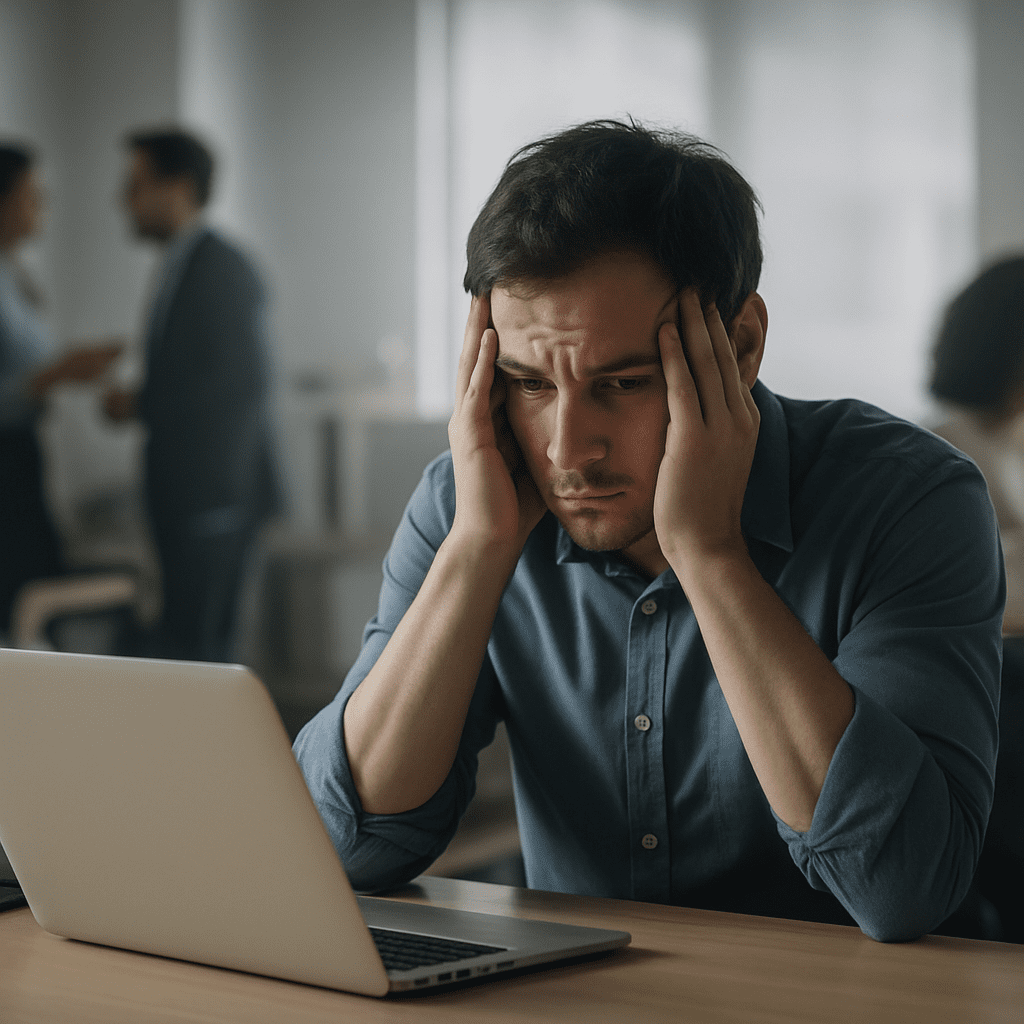

While emotional symptoms often take center stage in diagnosing and treating depression, the cognitive side effects of depression frequently remain in the background—undervalued and underreported. Individuals struggling with depression may describe difficulties in remembering names, staying focused during conversations, or completing once-routine tasks. These are not fleeting distractions or byproducts of sadness; they are indicative of cognitive dysfunction that can significantly impair functional independence and productivity.

Understanding the mechanisms behind depression and cognitive impairment requires looking at how the condition affects several domains of brain function. Executive functions—such as decision-making, planning, and mental flexibility—are often among the first to suffer. People with depression may find themselves indecisive, unable to organize their thoughts, or struggling with goal-directed behavior. At the same time, working memory—the ability to hold and manipulate information in one’s mind—can be impaired, making multi-step processes feel overwhelming or impossible.

Studies using functional MRI have shown that depression is associated with hypoactivity in the prefrontal cortex, a region responsible for higher-order cognitive functions. Concurrently, hyperactivity in the amygdala, which processes emotional responses, may hijack attention and disrupt cognitive equilibrium. This neurobiological imbalance contributes to the persistent experience of “brain fog” that so many with depression report—an apt metaphor for the blurred lines between cognition and mood.

How Mood Disorders Disrupt Memory, Focus, and Mental Clarity

Cognitive symptoms of depression affect nearly every facet of mental performance. One of the most distressing effects is the way depression interferes with memory. This impairment can take the form of forgetfulness, difficulty recalling events, or even an inability to encode new information properly. People often report reading the same passage multiple times without absorbing it or forgetting where they placed everyday items. These lapses are not imagined—they reflect real disruptions in the brain’s ability to form and retrieve memories.

Short-term memory, particularly, is vulnerable in the context of cognitive depression. Research suggests that hippocampal volume—an area crucial for memory consolidation—is often reduced in individuals with chronic depression. Neuroinflammation and stress-induced damage to neural circuits exacerbate these impairments, making it harder to retain new experiences or information. As the brain works overtime to manage emotional dysregulation, fewer resources remain available for clear, focused thinking.

Attention span also diminishes as depression takes hold. Concentrating on a single task becomes taxing, especially when the mind is constantly preoccupied with negative self-talk or ruminative thoughts. This is not simply a matter of “not trying hard enough” to focus; rather, it reflects neurochemical alterations, particularly in dopamine and norepinephrine pathways, that are essential for sustained attention and mental effort. The result is a pervasive mental fatigue that can undermine work performance, academic success, and interpersonal interactions.

Cognitive Depression: When Mental Clarity Becomes a Daily Struggle

The term “cognitive depression” is increasingly used in academic and clinical circles to describe a subtype of depression where cognitive dysfunction is not merely present but predominant. For some individuals, the most disabling aspects of their depression are not mood-related at all. Instead, they find themselves unable to think clearly, remember important information, or make decisions—symptoms that persist even when the sadness and anxiety have abated.

This cognitive dimension of depression is often resistant to standard antidepressant medications, which tend to target mood symptoms more directly. Even after emotional improvement, the cognitive side effects of depression can linger, a phenomenon known as residual cognitive symptoms. These residuals can interfere with recovery, perpetuating the cycle of dysfunction and increasing the risk of relapse.

Cognitive depression affects people across all age groups, but it poses particular risks for older adults, in whom it may be mistaken for early signs of dementia. This overlap complicates diagnosis and can lead to delayed or inappropriate treatment. Understanding the distinction between depression-related cognitive decline and true neurodegenerative processes is crucial for accurate assessment and effective intervention. Neuropsychological testing, combined with a thorough clinical history, often helps distinguish between the two.

Neurobiological Roots: Brain Changes Underlying Cognitive Symptoms of Depression

The cognitive symptoms of depression are deeply rooted in measurable brain changes. Advanced neuroimaging studies have revealed that depression alters the structure and function of several brain regions central to cognition, including the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and anterior cingulate cortex. These areas govern attention, memory, emotion regulation, and executive control—functions that are typically impaired in people with depression.

One of the most consistent findings is reduced connectivity within the brain’s default mode network (DMN), which is involved in introspection, memory, and self-referential thought. Disruptions in this network contribute to both depressive rumination and difficulty focusing on external tasks. Additionally, chronic stress, often associated with long-term depression, elevates cortisol levels and accelerates hippocampal atrophy. These biological insults impair the brain’s plasticity—the ability to adapt, learn, and form new connections.

At the molecular level, depression is associated with decreased levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein vital for neurogenesis and cognitive resilience. Lower BDNF levels correlate with poorer memory performance and slower information processing. Furthermore, neuroinflammation—a hallmark of major depressive disorder—can interfere with synaptic communication, reducing the efficiency of neural signaling and exacerbating cognitive deficits.

Everyday Life with Cognitive Impairment in Depression: Real-World Impacts

The effects of depression and cognitive impairment extend far beyond clinical settings. In the workplace, reduced mental clarity can result in diminished productivity, missed deadlines, and strained professional relationships. Tasks that once seemed routine may become insurmountable, leading to a sense of failure and further deepening the depressive cycle. Cognitive dysfunction can also impair communication, making it difficult to follow conversations, remember appointments, or engage meaningfully in social contexts.

At home, these impairments affect decision-making and problem-solving. Individuals may struggle with managing finances, organizing household responsibilities, or navigating family dynamics. For students, academic performance often declines—not due to a lack of intelligence or effort, but because depression clouds the ability to think and focus. These real-world consequences illustrate how the cognitive side effects of depression undermine independence and self-efficacy.

Loved ones may misinterpret cognitive symptoms as laziness, forgetfulness, or indifference, not realizing they are manifestations of a broader mental health condition. This misunderstanding can lead to feelings of guilt or shame, further isolating the individual. Increasing public and interpersonal awareness about how depression affects thinking is essential for reducing stigma and fostering compassion.

Diagnosis and Recognition: Why Cognitive Symptoms Are Often Missed

Despite their significance, the cognitive symptoms of depression are frequently overlooked in clinical evaluations. Many standard diagnostic tools for depression focus on emotional and behavioral symptoms, offering only cursory assessments of cognitive function. Patients themselves may struggle to articulate their cognitive difficulties or may assume that forgetfulness and mental fatigue are just part of “getting older.”

Primary care physicians, who are often the first point of contact for those with depression, may lack the time or specialized training to assess cognitive domains thoroughly. As a result, many individuals live with untreated or inadequately managed cognitive impairment for years, believing it to be an immutable part of their personality or aging process.

Advocates within the mental health field are calling for more comprehensive screening protocols that include specific questions about attention, memory, and decision-making. Neurocognitive assessments, either through brief in-office tools or full neuropsychological batteries, can provide valuable insights and guide more tailored interventions. Recognizing cognitive depression as a legitimate clinical concern is the first step toward more effective treatment strategies.

Treatment Pathways: Addressing Both Mood and Cognitive Symptoms

Managing depression and cognitive impairment requires a dual-focus approach. While antidepressants remain a cornerstone of treatment, they are often insufficient for resolving cognitive deficits on their own. Emerging research suggests that certain medications, such as vortioxetine and bupropion, may offer more pronounced cognitive benefits due to their unique pharmacological profiles. These drugs modulate multiple neurotransmitter systems, including serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine, which are all implicated in cognition.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has long been effective for treating depression, and adapted forms of CBT can also help improve cognitive symptoms. Techniques that focus on restructuring negative thought patterns, enhancing problem-solving skills, and promoting mental flexibility may indirectly boost cognitive performance. Moreover, newer interventions such as cognitive remediation therapy—originally developed for schizophrenia—are now being explored in depressive disorders to directly target cognitive dysfunction.

Lifestyle modifications play a vital role as well. Regular physical activity increases BDNF levels and promotes neurogenesis, offering both mood and cognitive benefits. Mindfulness practices have been shown to enhance attention and working memory while reducing depressive rumination. Diet, sleep hygiene, and social engagement also influence brain health and should be integrated into a comprehensive treatment plan. These multifaceted approaches recognize that cognitive symptoms of depression deserve targeted attention, not passive observation.

Preventive Strategies and Long-Term Outlook for Cognitive Recovery

While treatment is essential, prevention of cognitive decline in depression is equally important—particularly for individuals with recurrent or chronic episodes. Early intervention, ideally at the first signs of depression, may help preserve cognitive function over time. This is especially relevant for younger populations, whose brains are still developing, and for older adults at increased risk of cognitive deterioration.

Protective strategies include building cognitive reserve through lifelong learning, intellectual engagement, and diverse experiences. These activities help create alternative neural pathways that can compensate for areas affected by depression. Social connection is another critical factor; isolation not only worsens mood but also diminishes cognitive stimulation, accelerating decline.

Long-term prognosis varies depending on individual factors such as age, treatment adherence, and comorbidities. However, research increasingly supports the idea that cognitive recovery is possible with sustained effort and appropriate care. Neuroplasticity allows the brain to reorganize and strengthen itself, particularly when supported by therapeutic and lifestyle interventions. Reframing depression not just as an emotional disorder but as a condition that also affects thinking can empower individuals and clinicians to pursue more holistic and hopeful treatment goals.

Reclaiming Clarity: Why Understanding Depression and Thinking Is Essential for Full Recovery

The relationship between depression and thinking is not incidental—it is fundamental. For too long, cognitive symptoms of depression have been treated as peripheral concerns, secondary to the emotional pain that defines the disorder. Yet, as both research and lived experience attest, these cognitive challenges often form the core of the daily struggle for those with depression. When memory falters, attention dissipates, and mental clarity dims, the ability to function in life’s many roles begins to unravel.

By acknowledging and addressing the cognitive side effects of depression, we validate the full spectrum of suffering that individuals experience. More importantly, we open new pathways to healing—ones that prioritize cognitive health as an integral part of mental wellness. Whether through targeted medication, therapy, lifestyle change, or societal awareness, the journey to recovery must include the restoration of clear, confident thinking.

Understanding cognitive depression not only reshapes how we treat this condition but also redefines what recovery means. It is not merely the alleviation of sadness or anxiety—it is the reawakening of a mind that had grown dim. And in that renewal of focus, memory, and mental agility lies the true measure of healing.

Frequently Asked Questions: Depression and Cognitive Impairment

1. Can cognitive symptoms of depression improve without medication?

Yes, cognitive symptoms of depression can sometimes improve without pharmacological intervention, but this often depends on the severity and duration of the depression. Non-pharmacological approaches like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), and structured lifestyle changes—including exercise and sleep hygiene—have shown promise in mitigating the cognitive side effects of depression. These strategies can enhance neuroplasticity and reduce mental fatigue, helping the brain recover from the fog that often characterizes depression and thinking disruptions. Additionally, cognitive training exercises, such as computerized brain games, have been used to improve attention and memory, especially when used consistently. However, in moderate to severe cases, medication may still be necessary to address both mood and cognitive symptoms of depression more effectively.

2. Why do some people experience cognitive depression even after their mood improves?

Many individuals find that even when they no longer feel sad or anxious, they continue to struggle with forgetfulness, mental slowness, or trouble focusing. This phenomenon is often linked to residual depression and cognitive impairment, where the emotional symptoms subside, but cognitive functioning does not fully rebound. This disconnect is increasingly recognized in the clinical community, especially in cases of treatment-resistant or recurrent depression. Researchers believe that changes in brain structure—such as reduced hippocampal volume or persistent neuroinflammation—may explain why cognitive symptoms of depression can outlast mood disturbances. Addressing this specific pattern, known as cognitive depression, requires targeted treatment approaches beyond traditional antidepressants, including cognitive remediation therapy or medications like vortioxetine that are designed to support cognitive function.

3. How can I tell if memory problems are due to depression and not early dementia?

Differentiating between depression and early-stage dementia can be challenging, especially in older adults. One key distinction lies in how memory issues present: depression-related memory problems often fluctuate and may improve with encouragement or structured tasks, whereas dementia tends to cause more progressive and irreversible decline. People experiencing depression and thinking difficulties often remain aware of their cognitive lapses, expressing frustration or concern. In contrast, those with early dementia may show less insight into their impairments. Clinicians typically use neuropsychological evaluations to assess the pattern of cognitive impairment, helping to distinguish between cognitive symptoms of depression and signs of neurodegeneration. It’s crucial to seek early evaluation, as timely diagnosis can lead to more effective management and improved outcomes.

4. Do lifestyle factors influence the severity of depression-related cognitive impairment?

Absolutely. Lifestyle choices significantly influence how strongly depression and cognitive impairment manifest. Chronic stress, poor sleep, sedentary behavior, and nutrient-poor diets can all exacerbate the cognitive side effects of depression. On the other hand, regular aerobic exercise, adequate sleep, social engagement, and omega-3 fatty acid intake have been associated with better cognitive resilience. Activities that promote mental stimulation—such as learning a new language or engaging in artistic pursuits—may also reduce the impact of cognitive depression. Addressing lifestyle habits alongside conventional treatments creates a more holistic approach to improving both mood and cognition.

5. Are young adults at risk of cognitive depression, or is it mainly an issue for older adults?

Contrary to popular belief, young adults are not immune to the cognitive challenges of depression. While older adults may be more vulnerable to neurodegenerative changes, young people experiencing depression often report significant issues with focus, motivation, and memory. These impairments can affect academic performance, job responsibilities, and personal relationships. Moreover, untreated cognitive symptoms of depression in young adults may hinder brain development and executive function during critical periods of neuroplasticity. Recognizing that depression and thinking difficulties occur across the lifespan is essential for early intervention and long-term cognitive health.

6. Can workplace performance suffer due to the cognitive side effects of depression, even if emotional symptoms are under control?

Yes, many individuals find that even after their mood has stabilized, the lingering cognitive side effects of depression can undermine their performance at work. This may include difficulty concentrating during meetings, forgetting deadlines, or struggling to complete multi-step tasks. These symptoms can lead to reduced productivity, misunderstandings with colleagues, and even job loss if unrecognized. Employers and supervisors may not always be aware that depression and cognitive impairment can persist in this way. Open communication and workplace accommodations—such as flexible deadlines or reduced task loads—can help mitigate these effects while supporting cognitive recovery.

7. Are there specific brain regions most affected by cognitive symptoms of depression?

Research has consistently identified several brain regions involved in depression and thinking impairments. The prefrontal cortex, which governs decision-making and attention, often shows reduced activity in people with depression. The hippocampus, responsible for memory consolidation, may shrink in response to chronic stress or elevated cortisol levels. Additionally, the anterior cingulate cortex and amygdala—regions involved in emotional regulation—play roles in the intersection between mood and cognition. These neural changes help explain why cognitive depression can affect memory, focus, and executive function even in the absence of overt sadness. Understanding the neural underpinnings of depression and cognitive impairment enhances our ability to tailor treatments that restore mental clarity.

8. Is it possible to prevent cognitive decline in people with recurrent depression?

Prevention of cognitive decline in individuals with recurrent depression is a growing focus of mental health research. While no strategy guarantees protection, early intervention, regular mental health checkups, and sustained treatment adherence are all associated with better cognitive outcomes. Preventive efforts often include psychoeducation to help patients recognize early warning signs of relapse, thereby reducing cumulative cognitive damage. Additionally, activities that build cognitive reserve—such as education, intellectually engaging work, and complex hobbies—may act as buffers against the progression of cognitive symptoms of depression. Maintaining an anti-inflammatory lifestyle, with adequate exercise and nutrition, may also help protect brain health over time.

9. How does depression affect social cognition and interpersonal relationships?

Cognitive depression does not only affect internal mental processes; it also interferes with social cognition—the ability to interpret and respond to the emotions and intentions of others. People with depression and thinking impairments may misread social cues, withdraw from conversation, or interpret neutral remarks as negative. These misinterpretations can lead to interpersonal conflict and social isolation, reinforcing the depressive cycle. Even basic communication tasks—like recalling a friend’s name or keeping up with a conversation—may become mentally taxing. Addressing social cognition within treatment plans is important, as improving interpersonal functioning can reduce loneliness and accelerate emotional and cognitive recovery.

10. Are there innovations in treating the cognitive side effects of depression on the horizon?

Several exciting developments are emerging in the treatment of cognitive side effects of depression. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a non-invasive brain stimulation therapy, is being explored for its potential to target areas of the brain involved in attention and memory. Digital therapeutics, including mobile apps that deliver real-time cognitive training, are gaining traction as adjunct tools. Pharmacological innovations like vortioxetine and novel glutamate modulators are also showing promise in treating cognitive depression without the sedative side effects of older medications. Furthermore, machine learning algorithms are being developed to predict which patients are most likely to experience depression and cognitive impairment, allowing for more personalized interventions. These emerging tools represent a new frontier in mental health care—one that takes the cognitive dimension of depression as seriously as the emotional.

Conclusion: Recognizing Cognitive Depression as a Core Component of Mental Health

In our evolving understanding of mental health, it has become abundantly clear that depression is far more than a disorder of mood. It is a condition that reverberates throughout the brain’s cognitive systems, shaping how we think, remember, focus, and process the world around us. The persistent fog of mental fatigue, the forgetfulness, the inability to concentrate—these are not just collateral symptoms. They are integral expressions of the disorder itself. Recognizing depression and cognitive impairment as interconnected opens the door to more comprehensive care, rooted in science, compassion, and clarity.

When we examine the cognitive side effects of depression with the same urgency and depth as its emotional symptoms, we begin to understand just how deeply mood disorders can affect daily functioning. These cognitive symptoms of depression—whether they involve memory lapses, difficulty concentrating, or slowed thinking—must be validated, assessed, and addressed directly if recovery is to be complete. We can no longer afford to sideline these cognitive impairments or assume they will disappear on their own.

There is also an urgent need to recognize cognitive depression as a legitimate clinical phenomenon—one that may persist even after mood stabilizes and that demands targeted intervention. Advances in neuroscience continue to uncover the biological underpinnings of depression and thinking difficulties, helping clinicians and researchers refine therapeutic approaches. Emerging treatments, both pharmacological and behavioral, offer renewed hope for those navigating the dual burden of emotional and cognitive challenges.

Ultimately, the path forward lies in integrating these insights into routine care and public awareness. Whether through personalized medication plans, cognitive therapies, or lifestyle interventions that nourish the brain, we have the tools to support not just emotional healing but cognitive restoration. In doing so, we empower individuals to reclaim their full mental capacity—and with it, their confidence, independence, and quality of life.

By understanding depression and cognitive impairment as deeply interwoven, we begin to see mental health through a sharper, more accurate lens—one that reflects the full complexity of the human mind. In that clarity, both scientific and personal, lies the potential for a more complete and enduring recovery.

Further Reading:

Cognitive and neurological impairment in mood disorders