Dementia is a broad clinical term that refers to a decline in cognitive function severe enough to interfere with daily life. Within this spectrum of conditions, one subtype that often escapes public awareness yet plays a vital role in clinical practice is dementia without behavioral disturbance. In many medical records, this is coded under the umbrella of unspecified dementia, a term that is sometimes misunderstood. While much of the public discourse focuses on more visible and advanced stages of dementia that include agitation, aggression, or psychosis, many individuals live with subtler forms of the disease that are nonetheless deeply impactful. Understanding these less conspicuous forms is essential not only for accurate diagnosis but also for providing tailored care that respects the individual’s dignity and evolving needs.

You may also like: How to Prevent Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease Naturally: Expert-Backed Strategies to Reduce Your Risk Through Lifestyle and Diet

Unpacking the Concept of Unspecified Dementia

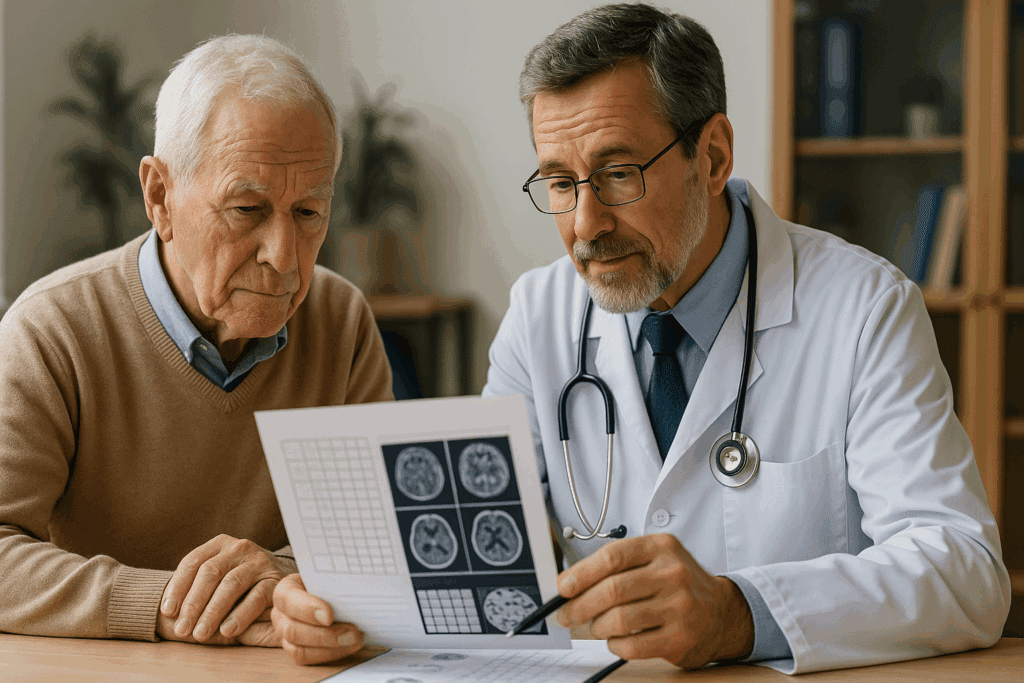

The term “unspecified dementia” is typically used when the diagnosing clinician recognizes signs of cognitive impairment consistent with dementia but lacks sufficient information to specify the exact type. This designation does not imply a less severe condition, nor does it suggest that the dementia is atypical. Instead, it often reflects either an early stage of the disease, limited clinical information, or overlapping features that do not clearly point to one subtype such as Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, or Lewy body dementia. For example, a patient may present with memory loss and executive dysfunction, but without the neuroimaging or neuropsychological testing needed to confidently assign a more precise label. In such instances, a diagnosis of unspecified dementia is made to ensure the patient receives care while further evaluations are underway.

This category is particularly common in primary care settings and among older adults who may have multiple comorbidities, making differential diagnosis challenging. Additionally, in some healthcare systems where diagnostic tools are less accessible, unspecified dementia may be used as a provisional or working diagnosis. It is a pragmatic choice that reflects real-world constraints in clinical practice while signaling the need for continued observation and refinement of the diagnosis.

What Does It Mean to Have Dementia Without Behavioral Disturbance?

Dementia without behavioral disturbance refers to individuals who exhibit cognitive decline but do not present with disruptive psychological or behavioral symptoms. These patients may experience forgetfulness, poor judgment, or disorientation, yet they remain calm, cooperative, and socially appropriate in most interactions. This presentation stands in contrast to more advanced or complicated forms of dementia that involve agitation, aggression, paranoia, delusions, or hallucinations. Importantly, the absence of behavioral disturbances does not equate to a benign disease trajectory. Rather, it underscores the need for vigilant cognitive monitoring, as behavioral changes may still emerge later in the disease course.

From a caregiving and clinical perspective, the distinction is significant. Individuals with dementia without behavioral disturbance often benefit from a more stable environment and may maintain a higher degree of independence for longer periods. However, the subtlety of symptoms can also delay diagnosis, as family members or caregivers may dismiss early signs as normal aging or minor forgetfulness. This delay can result in missed opportunities for early intervention, care planning, and engagement in cognitive therapies that might slow disease progression or enhance quality of life.

Challenges in Diagnosing Dementia Without Behavioral Symptoms

Diagnosing any form of dementia is inherently complex, but the challenge becomes even greater when behavioral disturbances are absent. These disturbances often serve as the red flags that prompt medical evaluations. In their absence, clinicians must rely more heavily on cognitive assessments, longitudinal observation, and input from family members or caregivers. Screening tools such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) or the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) can be valuable, but they are not definitive. The diagnosis of dementia without behavioral disturbance therefore requires careful clinical judgment and, ideally, corroborative evidence from neuroimaging or neuropsychological testing.

Further complicating matters is the reality that patients themselves may underreport symptoms due to embarrassment, denial, or lack of insight into their cognitive decline. This phenomenon, known as anosognosia, can lead to misleading clinical impressions and delayed referrals to specialists. In cases of unspecified dementia, where a precise etiology has not yet been identified, clinicians must strike a balance between caution and proactive care, ensuring that cognitive changes are neither minimized nor over-pathologized.

The Role of Early Detection and Screening

Early detection is a cornerstone of effective dementia care, regardless of whether behavioral symptoms are present. In fact, individuals with dementia without behavioral disturbance are prime candidates for early screening because their preserved social behaviors may mask underlying deficits. Routine cognitive screening for older adults, especially those with risk factors such as family history or cardiovascular disease, can help identify early cognitive changes that warrant further evaluation. Tools like the clock-drawing test or verbal fluency tasks can provide valuable insights when interpreted in context.

For clinicians and healthcare systems, embedding cognitive assessments into annual wellness visits or chronic disease management programs can normalize the process and reduce stigma. This proactive approach allows for timely discussions about care preferences, financial planning, and the potential use of cognitive-enhancing therapies. Importantly, it also provides an opportunity to educate families about the distinction between normal aging and early-stage dementia, which can be subtle yet meaningful.

Understanding the Cognitive Profile

One of the defining features of dementia without behavioral disturbance is its cognitive presentation. While the specific domains affected can vary, common patterns include memory impairment, reduced attention span, impaired executive function, and language difficulties. These cognitive changes are often most noticeable in situations requiring multitasking, abstract thinking, or rapid decision-making. In contrast, routine conversations and well-rehearsed tasks may remain largely intact, contributing to the perception that the individual is functioning well.

This uneven profile can be confusing for caregivers and clinicians alike. It is not uncommon for a person to perform adequately during a brief clinical visit but struggle significantly in real-world settings. As a result, collateral information from family, friends, or home health aides becomes crucial in painting an accurate picture of daily functioning. Standardized assessments can also help identify the specific cognitive domains that are most impaired, guiding treatment strategies and setting realistic expectations for disease progression.

Implications for Care Planning and Support

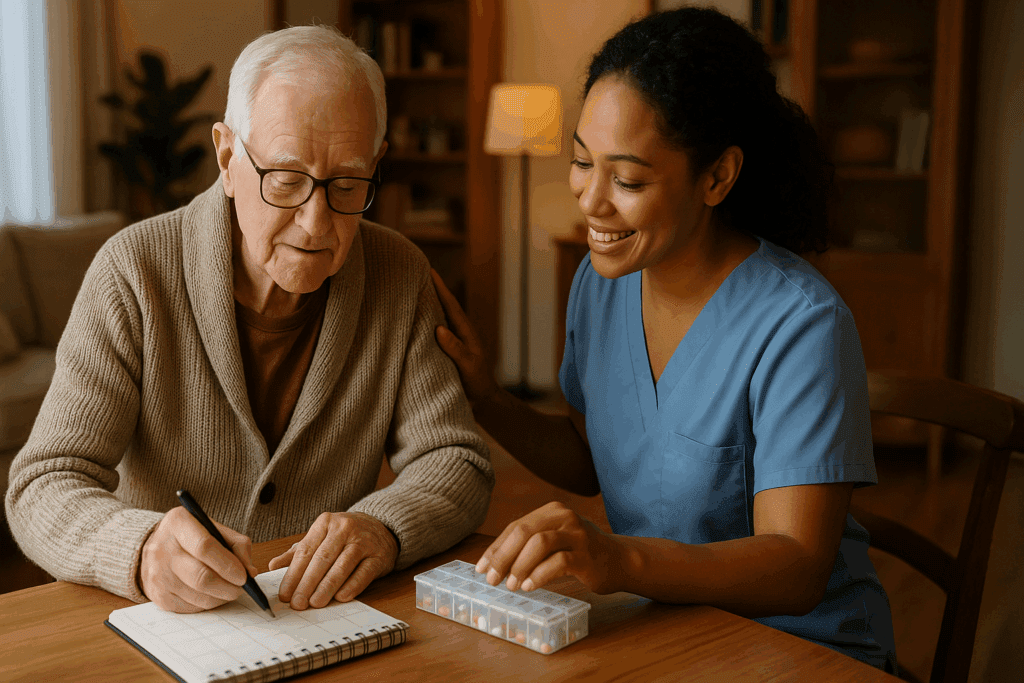

Care planning for individuals with unspecified dementia and no behavioral disturbances must take a nuanced approach. The absence of disruptive behaviors can make it easier to implement routines and maintain social relationships, but it also raises the risk that needs may be underestimated or overlooked. Comprehensive care planning should address current cognitive limitations while anticipating future changes. This includes discussions about living arrangements, transportation, medication management, and legal considerations such as power of attorney and advance directives.

Family caregivers play a pivotal role in this process, and they often require guidance and support to adapt to the evolving nature of the disease. Education about the expected trajectory, warning signs of deterioration, and available community resources can empower caregivers to provide effective support while safeguarding their own well-being. Importantly, caregiver burden can still be significant even in the absence of behavioral issues, underscoring the need for respite care and emotional support services.

Pharmacologic and Non-Pharmacologic Approaches

Treatment options for dementia without behavioral disturbance are largely similar to those for other forms of dementia, with some important distinctions. Cholinesterase inhibitors such as donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine, as well as NMDA receptor antagonists like memantine, are commonly prescribed to enhance cognitive function or slow decline. In patients with unspecified dementia, these medications may be initiated even in the absence of a definitive subtype, particularly if there is evidence of progressive cognitive decline.

Equally important are non-pharmacologic interventions. Cognitive stimulation therapy, physical exercise, and social engagement have all demonstrated benefits in maintaining or enhancing cognitive function. Structured routines, memory aids, and environmental modifications can support daily living and reduce the risk of accidents or confusion. The absence of behavioral disturbances may make individuals more receptive to these interventions, as they are likely to be more cooperative and motivated during the early stages of the disease.

Cultural and Social Dimensions of Dementia Without Behavioral Disturbance

Cultural perceptions of aging and cognitive decline can greatly influence the recognition and management of dementia. In some communities, memory lapses and confusion may be seen as normal aspects of aging, leading to underdiagnosis or delayed intervention. The absence of behavioral disturbances in unspecified dementia further complicates this picture, as individuals may continue to fulfill social roles or maintain decorum despite significant cognitive impairments. This cultural lens can obscure the need for medical evaluation and support services.

Social isolation is another critical factor. Individuals with subtle cognitive decline may withdraw from complex conversations or social engagements due to fear of embarrassment or frustration. This isolation can exacerbate cognitive decline and diminish quality of life. Encouraging inclusive, cognitively appropriate activities and fostering supportive social environments are essential strategies for mitigating this risk. Moreover, community outreach programs and culturally tailored education campaigns can help bridge gaps in awareness and access to care.

The Evolving Diagnostic Landscape

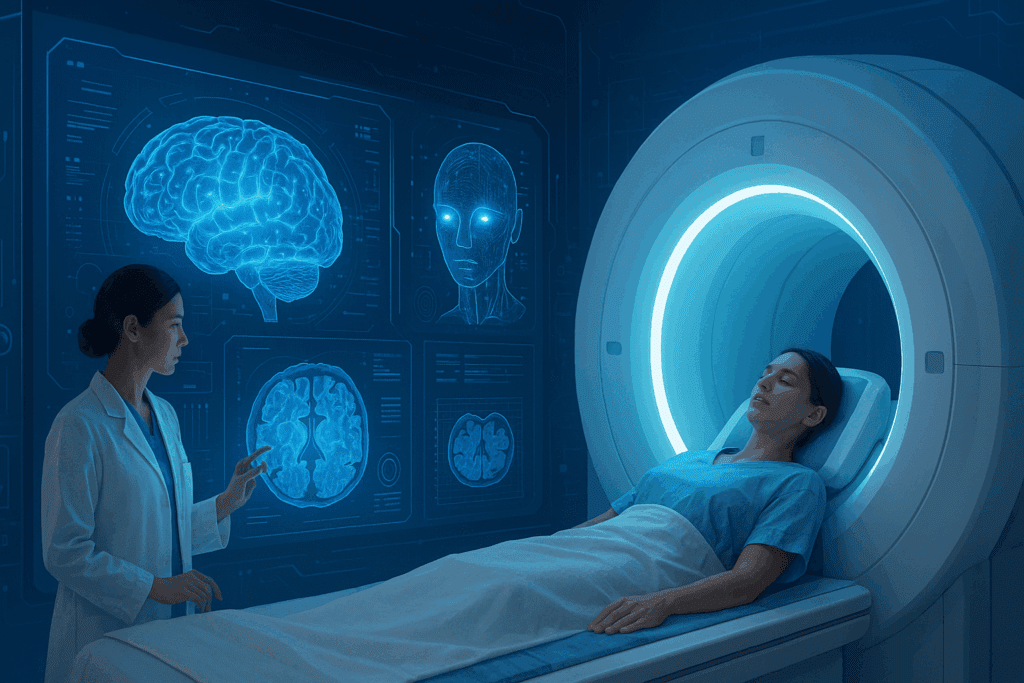

Advancements in neuroimaging, biomarkers, and artificial intelligence are reshaping the diagnostic landscape of dementia. These tools hold promise for improving the specificity of diagnoses, reducing reliance on unspecified dementia as a placeholder category. For example, positron emission tomography (PET) scans can detect amyloid plaques associated with Alzheimer’s disease, while cerebrospinal fluid analysis may reveal elevated tau proteins. Machine learning algorithms are also being developed to analyze patterns in speech, movement, and electronic health records to predict cognitive decline.

While these technologies are not yet universally available, they highlight the trajectory toward more personalized and precise dementia care. Until such tools are widely adopted, clinicians must continue to use unspecified dementia thoughtfully, recognizing its value as a temporary yet necessary classification that facilitates care while preserving diagnostic flexibility. Ongoing training in cognitive assessment and updates in diagnostic criteria are essential for clinicians to navigate this evolving field.

Revisiting the Trajectory of Behavioral Symptoms

It is crucial to understand that dementia without behavioral disturbance is not a static condition. Behavioral and psychological symptoms may emerge as the disease progresses, requiring adjustments in treatment and caregiving strategies. This underscores the importance of regular monitoring and flexible care plans that can adapt to new challenges. Families should be educated about potential future symptoms, such as sleep disturbances, mood swings, or delusional thinking, so they are not caught off guard.

Preparation for these changes can reduce caregiver stress and improve outcomes. Early discussions about potential behavioral issues can also facilitate the identification of triggers and coping strategies that may help delay or mitigate their onset. Moreover, early intervention with psychosocial support or medication can improve quality of life and potentially slow the progression of behavioral symptoms. In this context, dementia without behavioral disturbance represents a window of opportunity for proactive care.

Frequently Asked Questions: Understanding Dementia Without Behavioral Disturbance and Unspecified Dementia

1. How does dementia without behavioral disturbance affect long-term caregiving strategies?

While dementia without behavioral disturbance may initially seem easier to manage, it often requires a unique caregiving approach that emphasizes cognitive structure without relying on behavioral intervention techniques. Caregivers must focus on preserving autonomy, establishing routine cognitive stimulation, and maintaining consistent communication. Over time, as symptoms progress without overt behavioral disruption, the challenge becomes detecting more subtle cognitive shifts, which requires keen observation and record-keeping. Care strategies must evolve with the patient, integrating non-verbal cues and tracking functional decline that may not be readily apparent. Planning for future care needs becomes essential, as even individuals with dementia without behavioral disturbance may later transition into stages where behavioral symptoms emerge.

2. What are some lesser-known reasons why a diagnosis might be categorized as unspecified dementia?

Unspecified dementia may be used when cognitive symptoms do not neatly fit into established diagnostic categories, such as Alzheimer’s or vascular dementia. However, lesser-known reasons include patient reluctance to undergo further testing, cultural barriers to disclosing symptoms, or overlapping presentations involving multiple neurological conditions. In some cases, clinicians may also encounter incomplete medical histories or language barriers that make comprehensive evaluation difficult. Moreover, the presence of coexisting mental health conditions, like depression or anxiety, can obscure cognitive assessments, further justifying an initial diagnosis of unspecified dementia. This classification allows healthcare professionals to monitor symptoms and revisit the diagnosis as new data emerges.

3. Are there specific support tools tailored for individuals with dementia without behavioral disturbance?

Yes, several support tools are particularly effective for individuals with dementia without behavioral disturbance because they emphasize cognitive preservation over behavioral management. These include task-oriented calendars, personalized memory books, and electronic pill dispensers with visual and auditory reminders. Apps designed for early-stage dementia users can reinforce daily routines and provide gentle cognitive challenges, helping preserve function. Unlike tools developed for managing agitation or aggression, these support systems promote independence and engagement while reducing caregiver oversight. For individuals with unspecified dementia, especially those with subtle impairments, these tools can offer structure without stigmatizing the condition.

4. Can dementia without behavioral disturbance impact occupational functioning, even if social behavior appears intact?

Absolutely. Many individuals with dementia without behavioral disturbance continue to present as socially appropriate, which can lead others to overlook occupational challenges. However, deficits in memory, organization, attention to detail, and executive function can compromise performance in jobs that require multitasking or time-sensitive decisions. Because behavioral symptoms are absent, these cognitive limitations may be misattributed to burnout or stress, delaying appropriate interventions. Employers and coworkers may need education to recognize how cognitive decline can manifest subtly in the workplace. For individuals with unspecified dementia, occupational therapy can help adapt work responsibilities or suggest alternatives to support continued productivity.

5. How can clinicians track progression in patients diagnosed with unspecified dementia over time?

Tracking progression in patients with unspecified dementia often requires a multidisciplinary approach that combines periodic cognitive testing, caregiver feedback, and functional assessments. Tools such as the Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ) or the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale can help detect small changes in real-world functioning. Importantly, clinicians should also assess domains not always captured in brief cognitive tests, such as problem-solving, adaptability, and ability to manage finances. Advanced methods like digital monitoring of medication adherence, GPS tracking for wandering risk, or wearable devices that record sleep and activity patterns are emerging as supplementary tracking methods. These tools offer objective data to complement clinical impressions and help tailor evolving care plans for dementia without behavioral disturbance.

6. Are there any preventive strategies for delaying the progression of dementia without behavioral disturbance?

Though no cure exists, several preventive strategies have shown promise in delaying the progression of dementia without behavioral disturbance. Cognitive training exercises, bilingual language use, and learning new skills—such as playing an instrument—can build cognitive reserve. Cardiovascular health management, including controlling blood pressure and cholesterol, is especially important since vascular changes can exacerbate symptoms in both unspecified dementia and more defined subtypes. A Mediterranean-style diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids, leafy greens, and antioxidant-rich berries may also support brain health. Participation in meaningful social activities reduces isolation and has been correlated with slower cognitive decline. These strategies are proactive measures that emphasize prevention over crisis management.

7. In what ways does family education differ when caring for someone with dementia without behavioral disturbance?

Family education for dementia without behavioral disturbance focuses heavily on recognizing subtle cognitive cues and understanding the non-linear nature of cognitive decline. Unlike caregivers of individuals with disruptive symptoms, these families may struggle to accept the diagnosis due to the person’s calm demeanor and social functioning. Education must include training in how to identify nuanced signs of disorientation, repetitive questioning, or financial mismanagement, which may precede noticeable behavioral changes. Families are also advised to implement future planning discussions early, while the person with dementia can still participate meaningfully. When unspecified dementia is diagnosed, family education should emphasize the importance of staying observant and proactive, rather than reactive.

8. How do medical billing and insurance coverage differ when a patient is diagnosed with unspecified dementia?

Medical billing for unspecified dementia can present challenges because insurance providers may require additional documentation to approve certain treatments or therapies. Unlike more clearly defined diagnoses, such as Alzheimer’s disease, unspecified dementia codes can trigger requests for further evidence of medical necessity. Some long-term care insurance policies may delay benefits if the diagnosis lacks specificity, complicating access to support services. However, if clinicians carefully document cognitive decline and functional impairments, many insurers will eventually approve necessary interventions. For dementia without behavioral disturbance, coverage for non-pharmacological interventions—such as cognitive therapy or caregiver counseling—may also require justification due to the absence of overt symptoms.

9. What role does technology play in supporting patients with dementia without behavioral disturbance?

Technology plays an increasingly vital role in managing dementia without behavioral disturbance by offering discreet, non-intrusive support. Smart home devices can automate lighting, provide reminders for daily tasks, and enable remote monitoring by caregivers. Voice-activated assistants allow users to access information or make calls without navigating complex interfaces. In cases of unspecified dementia, where symptom presentation may be variable, wearable devices that monitor heart rate, mobility, or even gait changes can help flag early signs of progression. Furthermore, artificial intelligence is being explored for its potential to detect speech and behavior patterns that correlate with early cognitive decline, potentially enhancing diagnostic precision.

10. How does dementia without behavioral disturbance affect the emotional well-being of the individual diagnosed?

Living with dementia without behavioral disturbance can be emotionally complex for the person diagnosed, particularly in the early stages when insight is still intact. Individuals may experience anxiety, fear of future decline, or depression due to the awareness of their changing cognitive abilities. This emotional burden is often compounded by a lack of visible symptoms, leading others to underestimate their struggles or dismiss their concerns. Unlike individuals whose behavioral symptoms prompt immediate interventions, those with dementia without behavioral disturbance may not receive adequate emotional support. For patients with unspecified dementia, counseling, support groups, and mindfulness-based therapies can provide essential emotional scaffolding, promoting resilience and psychological adaptation.

Conclusion: Embracing a Comprehensive Approach to Unspecified Dementia

Understanding the complexities of dementia without behavioral disturbance—and the broader classification of unspecified dementia—is critical for improving diagnosis, care, and quality of life for affected individuals. While these terms may initially seem vague or noncommittal, they reflect a thoughtful approach to medical uncertainty, one that prioritizes timely support over diagnostic perfection. Recognizing the cognitive challenges inherent in these forms of dementia, even in the absence of behavioral symptoms, allows clinicians and caregivers to implement early, meaningful interventions that preserve autonomy and dignity.

This nuanced understanding also reinforces the importance of personalized care, where treatment plans are responsive not only to clinical data but also to the lived experiences of patients and their families. By moving beyond a narrow focus on the most visible symptoms and embracing the subtleties of cognitive decline, we can foster a more compassionate and effective approach to dementia care. In doing so, we acknowledge the full spectrum of the disease and commit to meeting individuals wherever they are in their journey, with empathy, clarity, and evidence-based support.