Understanding the Decline in Focused Attention

In recent years, researchers and clinicians have observed an unsettling trend: more and more people are losing this cognitive ability known as sustained attention. Also referred to as focused attention or deep concentration, this function enables individuals to hold their attention on a single task or stream of thought for an extended period. While it may seem like a minor inconvenience to lose the ability to stay focused, the ramifications for mental health, productivity, and overall cognitive well-being are far-reaching. This subtle erosion of attention spans has become increasingly apparent in clinical practice, educational settings, and workplaces alike, reflecting not just anecdotal concerns but a widespread neurocognitive shift that demands careful scrutiny.

Several studies have found that the average human attention span has been steadily decreasing. Once estimated at approximately 12 seconds in the early 2000s, it has reportedly dropped to around 8 seconds in the modern digital age. While some critics have questioned the methodology of such measurements, the broader consensus in the scientific and medical communities remains clear: more and more people lack this cognitive ability to maintain uninterrupted concentration for long periods. And the trend isn’t confined to children or adolescents—adults, including professionals and retirees, are also experiencing this cognitive erosion.

The pace of technological innovation, especially the proliferation of smartphones and social media, plays a central role in this phenomenon. Instant notifications, algorithm-driven content, and the infinite scroll mechanism create a perpetual state of distraction, training the brain to seek novelty and fragmenting attention. But digital overstimulation is not the sole culprit. Chronic stress, sleep disturbances, environmental noise pollution, and even certain medications have all been implicated in reducing an individual’s ability to maintain cognitive focus. The convergence of these factors is creating a perfect storm in which people are losing this cognitive ability across age groups and social demographics.

You may also like: How to Prevent Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease Naturally: Expert-Backed Strategies to Reduce Your Risk Through Lifestyle and Diet

The Crucial Role of Attention in Cognitive Function

Attention serves as the gateway to all other cognitive abilities. It determines what information gets processed, remembered, and acted upon. In a very real sense, without attention, there can be no learning, no memory consolidation, and no executive functioning. For this reason, the observation that more and more people lack this cognitive ability should raise immediate concern across disciplines. Attention is not merely a passive reception of sensory data; it is an active, dynamic system that prioritizes some stimuli over others, allowing us to engage meaningfully with our environment and make informed decisions.

This foundational role of attention is particularly evident in the context of working memory, the mental space in which we hold and manipulate information temporarily. If attention wavers, the contents of working memory become unstable, leading to errors in judgment, lapses in reasoning, and decreased problem-solving abilities. Furthermore, the brain’s prefrontal cortex—a region responsible for higher-order thinking—relies heavily on sustained attention to plan, organize, and control impulses. When people are losing this cognitive ability, they become more susceptible to impulsivity, procrastination, and mental fatigue.

A weakened attention system also disrupts emotional regulation. The ability to stay present and emotionally grounded is closely tied to focused cognitive engagement. Individuals who struggle to maintain attention may find themselves more prone to anxiety, irritability, and depressive symptoms, not because their emotional health is inherently fragile, but because the cognitive scaffolding that supports emotional resilience has eroded. In this context, the widespread loss of focused attention is not simply a mental nuisance; it becomes a risk factor for broader emotional and psychological instability.

Digital Distraction and Neuroplasticity

One of the most critical, yet often overlooked, aspects of attention loss is how it reshapes the brain itself. The brain is inherently plastic, meaning it adapts structurally and functionally in response to experience. Just as regular meditation can thicken the prefrontal cortex and improve attention, chronic distraction can rewire the brain toward shallowness. When individuals are constantly interrupted or multitasking, the brain learns to prioritize breadth over depth. As a result, even when opportunities for deep focus arise, the cognitive architecture required to sustain attention may be underdeveloped or atrophied.

Social media platforms, entertainment streaming services, and even educational technologies are designed to maximize engagement through intermittent reinforcement. This creates a behavioral loop not unlike gambling, where unpredictability fuels compulsive checking behaviors. Every time we check our phone mid-task, the brain gets a small dopamine reward, reinforcing the cycle of distraction. Over time, this rewiring compromises our natural ability to engage in deep, meaningful cognitive work. The concern is no longer hypothetical; neuroscientific imaging shows reduced gray matter density in attention-related brain regions among individuals who engage excessively with digital media.

When more and more people lack this cognitive ability, it’s not simply that they are more distracted; it is that their brain’s capacity to resist distraction is physiologically compromised. This insight has major implications for everything from education policy to corporate productivity models. Understanding this dimension of attention loss highlights the urgency of addressing it through targeted interventions and long-term strategies.

The Interplay Between Sleep, Nutrition, and Cognitive Vigilance

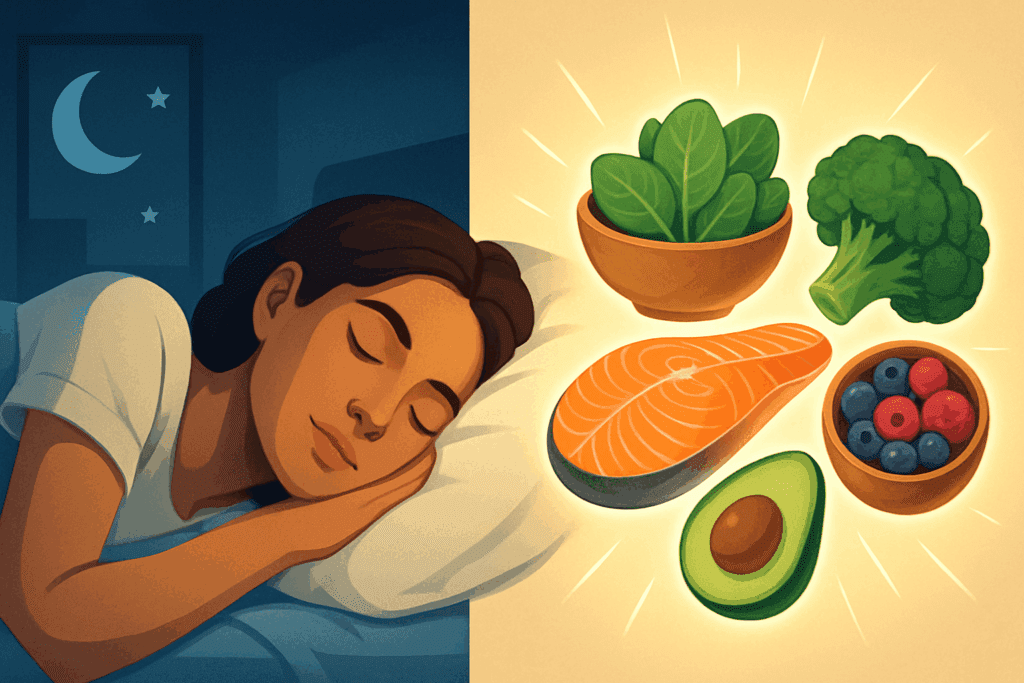

While digital distraction has taken center stage in the conversation, biological factors also play a critical role in attention regulation. Chief among them is sleep. Sleep deprivation—even mild, chronic forms—has a profoundly negative impact on sustained attention. The brain relies on deep, uninterrupted sleep to clear metabolic waste, consolidate memories, and recalibrate the neurotransmitter systems involved in focus and motivation. Studies have shown that a single night of poor sleep can reduce attentional capacity by up to 32%, and chronic sleep debt compounds these deficits, leaving the brain less responsive to cognitive demands.

Nutrition is another key pillar. Diets high in refined sugars and processed foods can lead to glycemic spikes and crashes, which impair mental clarity and disrupt neurotransmitter balance. In contrast, diets rich in omega-3 fatty acids, antioxidants, and complex carbohydrates support optimal brain function and protect against cognitive decline. Micronutrients such as magnesium, zinc, and B vitamins are particularly important for maintaining neural signaling and synaptic plasticity. Yet in many industrialized nations, nutritional imbalances are common, and these deficits may quietly undermine attention and executive function.

Moreover, the gut-brain axis—the bidirectional communication pathway between the gastrointestinal system and the central nervous system—has emerged as a critical factor in cognitive performance. Imbalances in gut microbiota can lead to increased inflammation and altered neurotransmitter production, both of which can impair attention and emotional regulation. When people are losing this cognitive ability, it often reflects a broader disruption in physiological equilibrium that goes far beyond mental distraction.

How Stress and Anxiety Undermine Attention

Stress is both a cause and a consequence of impaired attention. Under acute stress, the body releases cortisol and adrenaline, preparing for fight or flight. These hormones can temporarily enhance certain forms of alertness but are detrimental to sustained, nuanced attention. Chronic stress, in particular, depletes the brain’s capacity for sustained focus by impairing hippocampal function and reducing synaptic plasticity.

Anxiety exacerbates this issue. Individuals with anxiety often experience racing thoughts, hypervigilance, and intrusive worries that occupy cognitive bandwidth and interfere with task engagement. Over time, these patterns become self-reinforcing. The inability to focus increases feelings of inadequacy and stress, which in turn further impairs focus. When more and more people lack this cognitive ability, it reflects not just individual psychological states, but a cultural milieu that prioritizes speed and output over depth and introspection.

Furthermore, workplace structures and educational environments often perpetuate this cycle by rewarding multitasking and rapid responsiveness rather than depth of thought. The glorification of busyness reinforces habits that fragment attention, ultimately reducing overall productivity. Ironically, what appears as hyper-productivity is often cognitive inefficiency in disguise. Only by shifting cultural values and organizational expectations can we begin to create environments that support rather than sabotage sustained attention.

Medical Conditions That Disrupt Focused Cognition

Attention deficits are also linked to a range of clinical conditions beyond the psychosocial and environmental. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is perhaps the most well-known, but other neurological and psychiatric conditions can also erode attentional capacity. Depression, for instance, often manifests as a diminished ability to concentrate, sometimes referred to as “pseudo-dementia” due to its profound effects on cognitive functioning.

Traumatic brain injuries, even mild concussions, can lead to long-term attention deficits, particularly if left untreated. Neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease also impair attention networks, often long before memory loss becomes evident. Even autoimmune conditions, such as lupus or multiple sclerosis, can produce cognitive symptoms that resemble traditional attention disorders.

When people are losing this cognitive ability on a mass scale, it becomes essential to differentiate between transient, lifestyle-driven lapses and deeper medical concerns. Too often, attention deficits are either dismissed as laziness or over-pathologized without proper evaluation. A nuanced approach that considers both the biological and contextual causes of attention impairment is necessary to design effective treatment strategies and restore optimal cognitive functioning.

Proactive Strategies to Strengthen Cognitive Attention

Given the multifaceted nature of attention loss, interventions must be equally multidimensional. One of the most effective strategies for enhancing attention is mindfulness meditation. Numerous studies have demonstrated that regular mindfulness practice improves functional connectivity in brain regions associated with focus and emotional regulation. Even ten minutes of daily mindfulness can produce measurable changes in cognitive performance over time.

Another powerful tool is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which can help individuals identify and modify thought patterns that contribute to distraction and low motivation. CBT techniques, including thought reframing and structured goal-setting, enhance metacognitive awareness and allow individuals to regain a sense of control over their attention.

Physical exercise also plays a vital role. Aerobic activity increases blood flow to the brain and stimulates the release of neurotrophic factors that promote neural growth and repair. Particularly beneficial are activities that require coordination and strategic thinking, such as dance, martial arts, or team sports. These activities challenge the brain in complex ways that reinforce sustained attention and working memory.

Creating tech-free zones and scheduled digital detox periods can also help reset the brain’s reward circuitry. By reducing reliance on constant stimulation, individuals can recondition their cognitive systems to tolerate and even enjoy sustained periods of focus. When more and more people lack this cognitive ability, it is not a sign of inevitable decline but an opportunity to re-engage with practices that support attentional health.

Supporting Children and Adolescents in an Age of Distraction

The developmental implications of widespread attention loss are particularly concerning for younger generations. Children and adolescents are still forming the neural pathways that will govern their cognitive abilities for life. Excessive screen time, lack of unstructured play, and over-scheduled routines deprive them of the deep engagement necessary to cultivate attention.

Parents, educators, and policymakers must collaborate to create environments that promote focused learning. This means rethinking educational models that emphasize standardized testing and rote memorization in favor of experiential, project-based learning. It also requires a cultural shift toward valuing stillness, curiosity, and the slow cultivation of knowledge.

Outdoor play, imaginative storytelling, and uninterrupted reading time are not luxuries; they are developmental necessities. When children are given the space to engage deeply with their environment, they develop not just better attention, but greater emotional resilience and cognitive flexibility. These skills will serve them throughout life, particularly as they confront a world where more and more people are losing this cognitive ability.

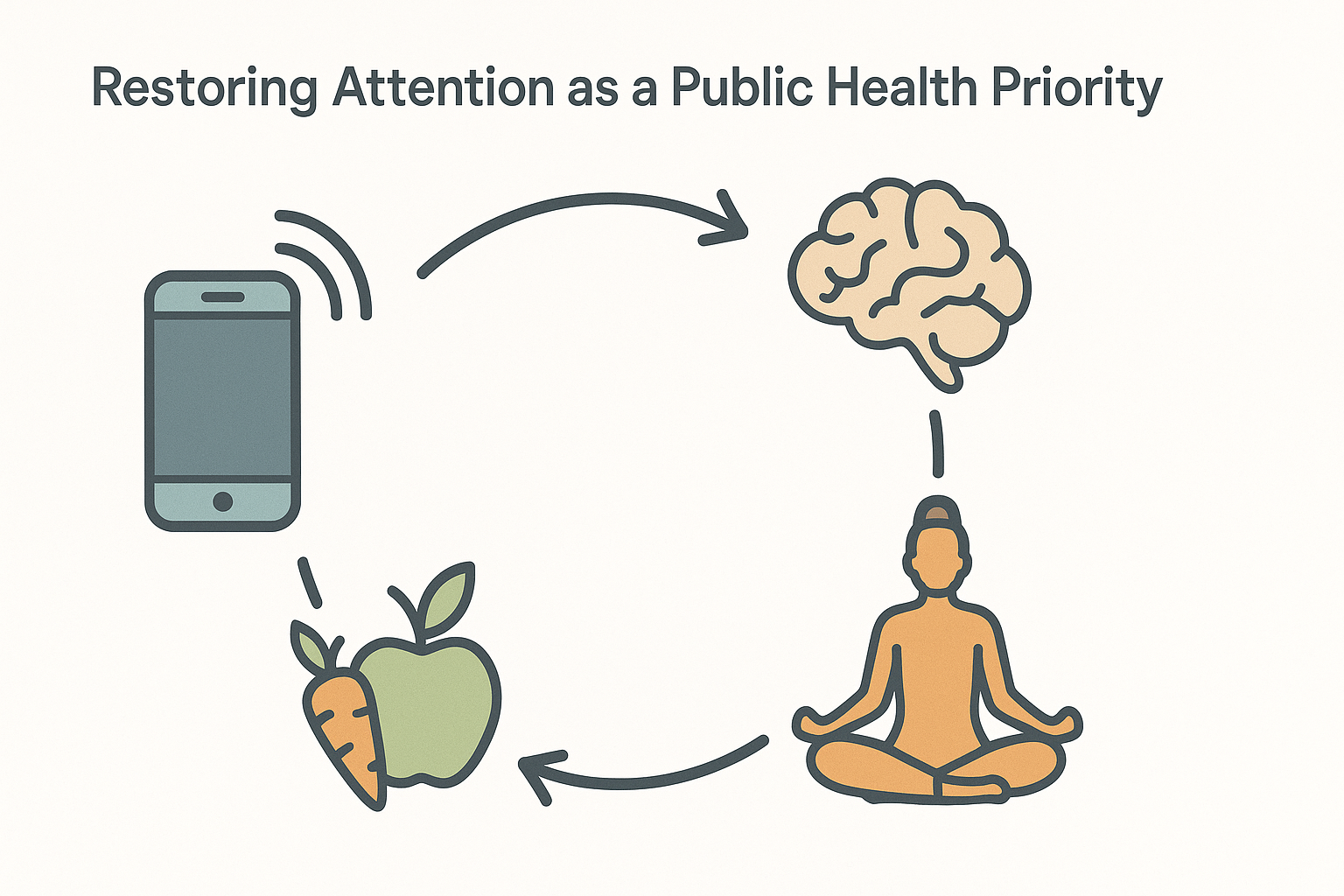

Restoring Attention as a Public Health Priority

The widespread erosion of focused attention is more than a personal inconvenience—it is a public health issue with implications for education, mental health, and workforce efficiency. As with other health crises, early intervention is key. Just as we have public health campaigns for smoking cessation or heart health, we must develop similar initiatives to educate people about cognitive hygiene.

This could include workplace wellness programs that emphasize focus over multitasking, public service announcements about the dangers of digital addiction, and policy reforms that incentivize longer recess and play periods in schools. Addressing this issue at a societal level ensures that interventions are not merely reactive but preventive, helping to reverse the trend before it becomes a generational norm.

Collaborations between neuroscientists, psychologists, educators, and urban planners can foster innovative solutions that embed attentional support into daily life. From designing quiet, contemplative public spaces to incorporating mindfulness training into school curricula, the possibilities are vast. But the first step is acknowledging that when people are losing this cognitive ability in ever-growing numbers, we are confronting not a niche problem but a defining challenge of our time.

Reclaiming Focus in a Distracted World

In a culture increasingly defined by haste, fragmentation, and overstimulation, the ability to sustain attention has become a rare and precious resource. When more and more people lack this cognitive ability, the ripple effects are felt across all aspects of society—from individual well-being to collective productivity and even democratic engagement. Fortunately, the neuroplastic nature of the brain offers hope. Attention can be retrained, strengthened, and restored through intentional practice, environmental redesign, and lifestyle modification.

Understanding why people are losing this cognitive ability requires a comprehensive view of the biological, psychological, and environmental factors at play. But perhaps more importantly, protecting and restoring this ability requires a cultural shift—a renewed commitment to depth over speed, presence over distraction, and intentionality over impulsivity. The good news is that this shift is within reach. By prioritizing attentional health as both an individual practice and a societal value, we can reclaim one of our most essential cognitive functions and, in doing so, protect the foundation of our mental and emotional lives.

As we move forward in an increasingly complex and demanding world, safeguarding attention may well be the key to unlocking not just personal clarity but collective well-being. And that is a goal worthy of our deepest and most focused effort.

Frequently Asked Questions: Addressing the Decline in Sustained Attention

1. Why are so many people struggling with sustained focus even when they’re motivated?

Motivation alone is no longer enough to ensure focus in today’s environment because the brain’s reward systems are constantly hijacked by hyper-stimulating inputs. Even highly motivated individuals are finding it harder to engage deeply because the neural circuitry that sustains attention has been weakened through overstimulation. When more and more people lack this cognitive ability, it’s often not a matter of willpower but a reflection of cumulative environmental overload. A motivated person may still check their phone 20 times an hour, not because they want to be distracted, but because their cognitive habits have been rewired to prioritize novelty over depth. This disconnect highlights how people are losing this cognitive ability through a combination of digital saturation and neurobiological fatigue.

2. Can attention loss be reversed, or is it a permanent condition?

The good news is that for most people, attention loss is not permanent. Neuroplasticity allows the brain to rebuild lost cognitive pathways if consistently supported with the right interventions. However, this process takes time and discipline, and it often requires lifestyle changes such as reduced screen time, better sleep hygiene, and mindfulness practices. When people are losing this cognitive ability, it doesn’t necessarily mean the damage is irreversible—but it does signal the urgent need for conscious retraining of the mind. Just as one can recover physical strength after prolonged inactivity, attention can be rehabilitated through targeted cognitive exercise.

3. How do social norms and work culture contribute to cognitive decline?

In many workplaces, constant availability and multitasking are equated with productivity, when in fact they are eroding focus and cognitive efficiency. The expectation to reply instantly to emails and messages creates a culture where deep work is devalued. When more and more people lack this cognitive ability, it is often because the environments they inhabit reward fragmentation over sustained engagement. This cultural pressure pushes even those with strong focus toward shallow work habits, reinforcing distraction as the default mode. Rebuilding attention on a broad scale requires not only individual action but a systemic redefinition of what it means to work well.

4. What role does emotional trauma play in reducing attention span?

Trauma alters the brain’s stress response systems and impairs the neural circuits involved in sustained attention. People with unresolved trauma may experience hypervigilance, dissociation, or racing thoughts—all of which make it difficult to concentrate. When people are losing this cognitive ability, especially in post-traumatic contexts, traditional attention-boosting techniques may not suffice. Trauma-informed approaches that integrate therapy, emotional regulation strategies, and somatic practices are often necessary to rebuild attentional capacity. In these cases, healing the mind must precede training it.

5. Are there generational differences in attention capacity due to digital exposure?

Yes, digital natives—those who have grown up with screens from early childhood—appear to have shorter attention spans and more difficulty with deep focus compared to older generations. This trend suggests that when more and more people lack this cognitive ability, the issue is not just about individual habits but developmental patterns. Children whose brains have been shaped around multitasking and instant feedback loops may struggle with boredom, patience, and delayed gratification. While generational adaptability is a strength, it also means that core cognitive skills must be taught with intention in ways that earlier generations may have acquired organically.

6. Could wearable tech or neurofeedback tools help rebuild attention?

Emerging technologies offer promising tools for measuring and enhancing attention. Devices that monitor brainwave patterns or heart rate variability can help users recognize when they are losing focus and offer cues to redirect attention. While not a cure-all, these tools provide valuable feedback loops that can accelerate cognitive retraining. When more and more people lack this cognitive ability, integrating real-time data with behavioral interventions creates a more personalized path to recovery. However, effectiveness depends on user consistency, and these tools should complement, not replace, foundational lifestyle changes.

7. What are the social consequences of widespread attention loss?

Declining attention spans impact more than individual productivity—they erode the quality of social interactions, civic engagement, and emotional presence. When people are losing this cognitive ability on a broad scale, conversations become shallower, relationships suffer, and collective problem-solving deteriorates. Public discourse becomes reactive rather than reflective, as nuanced thinking is replaced by quick takes and surface-level opinions. These trends have implications for democracy, education, and social cohesion, making attention loss not just a personal issue but a societal concern. Sustained focus underpins empathy, dialogue, and critical reasoning—all essential for a functioning society.

8. How can mindfulness and contemplative practices specifically rewire the brain?

Mindfulness doesn’t just calm the mind—it changes the structure and function of brain regions involved in attention and emotional regulation. Consistent practice enhances connectivity between the prefrontal cortex and the anterior cingulate cortex, improving both focus and impulse control. As more and more people lack this cognitive ability, mindfulness offers a scalable, low-cost intervention that addresses the root rather than the symptom. The act of repeatedly returning to the breath or body scan trains the mind to resist distraction and stay present. Over time, this practice fosters not only improved attention but greater resilience and emotional stability.

9. What are some overlooked factors that can impair attention?

Beyond digital distraction and stress, lesser-known contributors to attention decline include environmental toxins, chronic inflammation, hormonal imbalances, and even indoor air quality. For example, exposure to heavy metals like lead or mercury can impair cognitive development and focus. Poor ventilation or excessive carbon dioxide levels in closed environments have been linked to reduced decision-making and attention span. When more and more people lack this cognitive ability, it may reflect hidden environmental stressors that require multidisciplinary awareness. Addressing attention decline holistically means looking beyond the obvious and identifying subtle disruptors.

10. How can families create an attention-friendly home environment?

Establishing boundaries around screen time, creating quiet zones, and modeling focused behavior are crucial steps in building attentional resilience at home. Families that prioritize shared meals, reading, and creative play nurture habits that counterbalance digital overload. When people are losing this cognitive ability, home environments can serve as sanctuaries that reinforce stillness, reflection, and sustained engagement. Parents and caregivers play a central role by demonstrating attention-preserving habits themselves—putting down phones, limiting background noise, and encouraging open-ended exploration. Such practices not only benefit children but also foster a household culture of mindfulness and presence.

Conclusion: Rebuilding Focus in a Distracted World

As society grapples with rapid digital advancement and environmental overstimulation, it is no surprise that more and more people lack this cognitive ability that once defined human progress: sustained attention. The implications of this shift reach far beyond fleeting distractions, shaping the very fabric of how we think, work, learn, and connect. Understanding why people are losing this cognitive ability invites us to look beyond surface-level solutions and examine the deeper forces—technological, psychological, and cultural—that shape our cognitive realities.

Restoring attentional capacity requires a multifaceted response, combining neuroscience, behavioral change, and societal restructuring. Whether through contemplative practices, education reform, trauma-informed care, or environmental adjustments, each strategy contributes to a broader movement of cognitive restoration. Ultimately, regaining our focus is not merely about optimizing productivity; it is about reclaiming the clarity, creativity, and compassion that come from deep, sustained presence. In doing so, we reaffirm our collective capacity for meaningful engagement in a world that increasingly demands our fragmented attention.