The essence of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) lies in its structured, time-sensitive, and goal-directed approach to alleviating psychological distress. Unlike more exploratory psychodynamic therapies that delve into early life experiences without a defined endpoint, CBT is founded on the premise that specific, measurable progress can be achieved by targeting maladaptive thinking patterns and behaviors. Central to this approach are the cognitive behavioral therapy treatment goals that serve as both compass and catalyst—guiding the course of therapy while shaping tangible outcomes. In clinical settings, well-formulated goals in CBT can dramatically influence the effectiveness of the therapeutic alliance, client engagement, and the sustainability of treatment results long after therapy concludes.

You may also like: How Does CBT Work to Improve Relationships and Communication? Science-Backed Techniques for Getting Along with Others

Within this framework, CBT treatment goals are not arbitrary or cosmetic. They are crafted with clinical precision, drawing from empirically validated strategies that align with both the therapist’s theoretical orientation and the client’s personal values. These objectives provide structure and momentum to the therapeutic journey, helping individuals track their psychological development while remaining rooted in their day-to-day realities. Far from being a checklist, these goals reflect a dynamic, evolving process that mirrors the complexities of human cognition and behavior.

The ability to conceptualize and operationalize meaningful goals is both an art and a science—one that integrates psychological insight, behavioral data, and client collaboration. This article explores how the process of cognitive behavioral therapy goal setting not only improves clinical efficacy but also enhances patient autonomy, engagement, and long-term resilience.

The Role of Goal Setting in the Architecture of CBT

At the heart of CBT lies a fundamental belief in agency—that people can change their thoughts, behaviors, and emotional responses through intentional, structured efforts. Cognitive behavioral therapy goal setting operationalizes this belief, providing a concrete roadmap for therapeutic progress. Unlike vague aspirations, such as “feeling better,” goals in CBT are typically framed in observable, achievable terms. They may focus on reducing the frequency of panic attacks, increasing social interactions, challenging cognitive distortions, or adhering to sleep hygiene routines. These goals offer both client and therapist a shared language for tracking improvement.

Moreover, CBT therapy goals serve as motivational anchors that sustain engagement during difficult phases of treatment. Clients entering therapy often feel overwhelmed by emotional pain, confusion, or hopelessness. Specific, attainable goals transform this psychological fog into manageable segments, offering a sense of control and forward motion. The therapeutic process becomes less about navigating an amorphous psychological landscape and more about executing a strategic intervention plan.

In clinical practice, the benefits of clear goal setting are multidimensional. It enhances accountability, sharpens focus during sessions, and facilitates the use of evidence-based interventions. For instance, if a primary goal is to reduce avoidance behaviors associated with social anxiety, therapists can apply exposure techniques, thought records, and behavioral experiments specifically tailored to that outcome. Without such direction, therapy risks becoming aimless or diluted in its impact.

Cognitive Therapy Goals as a Mechanism for Behavioral Change

Although the term “cognitive” may suggest an emphasis on thoughts alone, cognitive therapy goals frequently encompass behavioral components that are tightly interwoven with cognitive patterns. For example, a client struggling with depression may hold maladaptive beliefs such as “I am worthless” or “Nothing will ever change.” These beliefs are not merely abstract ideas—they manifest behaviorally as withdrawal, procrastination, or neglect of basic self-care. In this context, one effective goal might be to increase engagement with pleasurable or mastery-oriented activities, a process known as behavioral activation.

This integration of cognitive and behavioral domains is a defining feature of CBT. Treatment goals thus function not only as indicators of psychological targets but also as scaffolding for behavioral experiments. Clients are encouraged to test the validity of their beliefs through real-life actions—attending a social event to challenge assumptions about rejection, for instance, or applying for a job to dispute beliefs about inadequacy. These experiments produce experiential evidence that can disconfirm irrational thoughts, thereby reinforcing cognitive restructuring.

Cognitive behavioral therapy treatment goals also facilitate desensitization to distressing stimuli. For clients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), one structured goal might be to reduce compulsive checking behaviors from twenty times a day to five, and eventually to none. This allows for a gradual exposure process with measurable benchmarks that instill confidence and signal progress. The interdependence between cognition and behavior becomes increasingly clear as clients see how shifting one domain can recalibrate the other.

Personalization and the Collaborative Nature of CBT Goal Setting

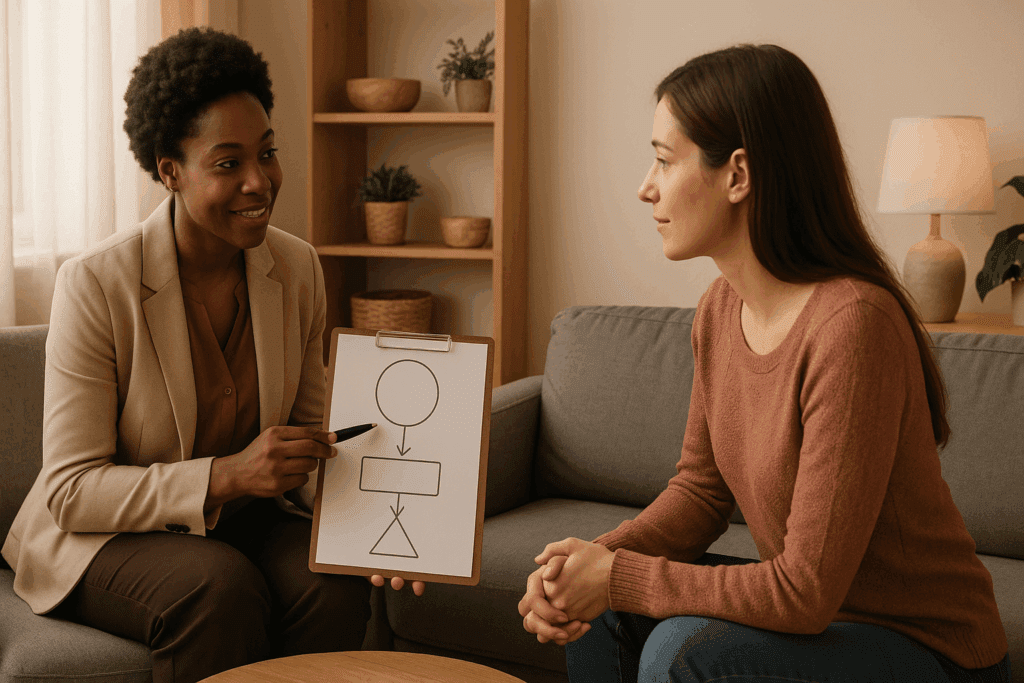

One of the most powerful aspects of CBT is its collaborative ethos. Rather than the therapist imposing a predefined set of objectives, the process of cognitive behavioral therapy goal setting is deeply client-centered. Therapists facilitate exploration of the client’s values, desires, and life context, ensuring that goals are personally meaningful and relevant. This personalization is not only ethical but essential; goals that resonate with the client’s lived experience are more likely to foster motivation and adherence.

Therapists often begin by asking open-ended questions that help surface underlying values: “What would your life look like without this anxiety?” or “What relationships or activities have you been avoiding due to depression?” These inquiries enable clients to articulate their own desired outcomes, which are then translated into therapeutic goals. A client may express a desire to rebuild a damaged relationship with a sibling or return to school after a mental health leave. From these narratives, specific CBT therapy goals can be drawn: increasing assertive communication, reducing self-defeating thoughts, or improving emotion regulation skills.

It is also important that these goals remain adaptable over time. As therapy progresses and clients experience growth, their priorities often shift. A goal that initially focused on symptom reduction may evolve into one centered around life enhancement or meaning-making. The therapist’s role is to support this evolution without losing sight of the original objectives, ensuring that the therapy remains responsive yet goal-directed. This dynamic interaction is one of the reasons CBT is so effective across a broad spectrum of mental health conditions, from anxiety and depression to PTSD and chronic stress.

From Abstract to Concrete: Translating Aspirations into CBT Goals Examples

Turning a client’s general desire for improvement into concrete objectives is a core skill in CBT. Vague aspirations such as “I want to be happy” or “I need to stop being anxious” must be translated into operationalized goals that are actionable, measurable, and realistic. This transformation is not only practical but therapeutic; it helps the client move from a state of passivity into one of agency and clarity.

For example, a client presenting with generalized anxiety disorder may begin with a diffuse sense of unease and an overarching desire for peace of mind. Through structured dialogue, this can be translated into specific cbt goals examples such as reducing catastrophic thinking by identifying and challenging cognitive distortions at least once per day, or using diaphragmatic breathing techniques during stressful moments three times per week. These goals are specific enough to be tracked but flexible enough to accommodate fluctuations in mood and life events.

Similarly, a client with social anxiety may aspire to “be more confident.” While laudable, this aspiration lacks the specificity required for CBT work. With therapeutic guidance, it can be broken down into cognitive behavioral therapy treatment goals such as initiating one new conversation per week, attending one social gathering per month, and reframing self-critical thoughts using cognitive restructuring worksheets. Each of these goals not only fosters behavioral exposure but also facilitates cognitive change.

Clients struggling with depression often benefit from goals centered on activation and cognitive reframing. Instead of a vague wish to “feel better,” CBT treatment goals might include scheduling one pleasurable activity daily, completing thought records three times per week, and practicing gratitude journaling to shift attentional bias toward positive experiences. In all cases, the emphasis is on small, achievable steps that build momentum over time.

Measuring Progress and Adjusting the Course of Therapy

Unlike therapies that prioritize exploration over evaluation, CBT places a strong emphasis on monitoring progress. This is not to reduce the therapeutic relationship to a series of metrics, but rather to ensure that interventions are effective and responsive. Regularly revisiting cognitive therapy goals allows both client and therapist to celebrate achievements, troubleshoot obstacles, and recalibrate expectations.

Progress in CBT is typically measured through a combination of client self-report, standardized assessments, and therapist observation. Clients may complete weekly symptom inventories, such as the Beck Depression Inventory or the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale, which provide quantitative feedback on emotional states. Meanwhile, qualitative indicators—such as improved interpersonal interactions, increased motivation, or greater emotional regulation—serve as equally valuable evidence of growth.

When goals are not being met, this is not interpreted as failure but as data. Perhaps the goals were too ambitious, the interventions ill-suited, or external stressors overwhelming. The therapist’s role is to engage in curious, nonjudgmental inquiry that invites collaboration: “What’s making this difficult right now?” or “Is this still the right goal, or should we pivot?” This reflective process keeps therapy attuned to the client’s evolving context and maintains therapeutic momentum even during challenging periods.

Adjusting goals is also essential when breakthroughs occur. A client who originally sought to reduce panic attacks may find themselves increasingly interested in long-term personal development, such as pursuing a meaningful career or nurturing spiritual well-being. CBT allows for this broadening of focus while maintaining the structure and intentionality that make it effective.

The Neurological and Psychological Foundations of CBT Goal Setting

Cognitive behavioral therapy goal setting is not merely a procedural element—it is grounded in well-established principles of human motivation and neuroplasticity. Goal-setting theory, a central tenet of motivational psychology, suggests that specific, challenging goals lead to higher performance than vague or easy ones. This is particularly relevant in CBT, where clients are often attempting to change long-standing habits and entrenched thought patterns.

Moreover, the act of setting and pursuing goals activates the brain’s reward circuitry, particularly regions such as the prefrontal cortex and the striatum. These areas are responsible for executive functioning, planning, and the anticipation of reward—all critical components in sustaining effort over time. By working toward clearly defined objectives, clients not only engage their cognitive resources more efficiently but also experience motivational reinforcement that strengthens commitment.

In addition, goal-directed behavior supports the restructuring of neural pathways. When clients consistently engage in new behaviors—such as challenging negative thoughts or facing feared situations—they reinforce new cognitive and behavioral patterns. Over time, these pathways become more dominant, reducing the automaticity of maladaptive responses. This is the very foundation of neuroplasticity, and it explains why consistent, goal-oriented practice is so vital in achieving sustainable change.

Empowerment, Relapse Prevention, and Life Beyond Therapy

One of the most enduring benefits of well-formulated CBT therapy goals is the empowerment they foster. As clients begin to meet their objectives, they often report an enhanced sense of agency, competence, and hope. This psychological momentum can extend beyond the confines of therapy, equipping individuals with lifelong tools for self-regulation and problem-solving.

Furthermore, clearly articulated goals in CBT serve as anchors for relapse prevention. Clients learn to identify the early warning signs of cognitive or emotional regression and apply the same tools that helped them achieve their initial gains. Whether it’s re-engaging in cognitive restructuring, resuming exposure tasks, or revisiting behavioral activation schedules, the therapeutic goals function as a kind of internal compass that can be reoriented whenever necessary.

Therapists can support this process by developing relapse prevention plans with clients during the final stages of therapy. These plans often include revisiting cognitive therapy goals, identifying high-risk situations, and reinforcing adaptive coping strategies. The goal is not to create dependency on the therapist, but rather to instill a robust internal framework that supports long-term resilience and psychological well-being.

Frequently Asked Questions: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Treatment Goals

1. How do CBT treatment goals differ across various mental health conditions?

CBT treatment goals are highly individualized and shaped by the specific symptoms, patterns, and functional impairments associated with each condition. For instance, goals in CBT for generalized anxiety disorder often focus on reducing rumination, challenging catastrophic predictions, and improving tolerance for uncertainty. In contrast, cognitive therapy goals for obsessive-compulsive disorder may involve reducing ritualistic behaviors through exposure and response prevention. In depression, CBT therapy goals commonly prioritize re-engaging in daily activities and altering negative core beliefs. These distinctions are not merely semantic—they reflect the therapeutic nuances that make cognitive behavioral therapy treatment goals effective across a wide spectrum of clinical presentations.

2. Can cognitive behavioral therapy goal setting be used in group therapy formats?

Yes, cognitive behavioral therapy goal setting can be remarkably effective in group therapy contexts, though the structure differs from individual therapy. Group settings often encourage participants to develop both shared and individual goals, promoting accountability and a sense of communal progress. Group members may benefit from observing how others approach similar cognitive therapy goals, gaining inspiration and refining their own strategies. Therapists facilitate goal alignment without compromising the personal relevance of each member’s objectives. Incorporating cbt goals examples into the group dynamic—such as practicing assertiveness or exposure tasks together—can enhance skill generalization and peer support.

3. How can therapists help clients overcome resistance to setting CBT therapy goals?

Some clients may feel intimidated, overwhelmed, or skeptical when asked to define CBT therapy goals, especially if past efforts at change were unsuccessful. Therapists can reduce this resistance by framing goals as flexible guideposts rather than rigid expectations. It’s also useful to co-create goals that align with a client’s values and language, rather than relying solely on diagnostic criteria. When clients feel ownership over their cognitive behavioral therapy treatment goals, they are more likely to invest in the process. Validating the client’s concerns and emphasizing the collaborative nature of cognitive behavioral therapy goal setting fosters empowerment and reduces defensive avoidance.

4. Are there cultural considerations in establishing CBT treatment goals?

Absolutely. Cultural background, social context, and belief systems can profoundly influence how clients perceive mental health, change, and personal achievement. Culturally competent clinicians recognize that CBT treatment goals must be framed in ways that respect and reflect the client’s worldview. For example, collectivist values might prioritize relational harmony or family roles over individual assertiveness, which means goals in CBT must account for those priorities. Effective cognitive behavioral therapy goal setting requires cultural humility and an understanding that “success” or “progress” may look different across cultural contexts. Therapists should ask open-ended questions to explore what wellness means for each client, tailoring goals accordingly.

5. How do therapists measure success when CBT therapy goals are subjective or abstract?

While CBT emphasizes measurable objectives, some goals—such as “feeling more confident” or “finding meaning”—can initially seem too abstract. In such cases, therapists use a process called behavioral anchoring, which involves identifying observable actions that reflect the underlying emotional or cognitive shift. For instance, if a goal is to build confidence, a cbt goals example might include initiating conversations at work or volunteering to lead a project. These behaviors become proxy indicators of abstract concepts. The art of measuring progress lies in translating cognitive therapy goals into specific behaviors, then tracking them consistently while remaining open to reevaluation.

6. Can cognitive therapy goals evolve into long-term life goals beyond therapy?

Yes, many cognitive therapy goals serve as stepping stones toward broader life aspirations. Once a client builds emotional regulation, challenges maladaptive beliefs, and establishes healthier behavioral patterns, their focus often shifts to long-term growth. This may include career advancement, rebuilding relationships, or pursuing creative or spiritual endeavors. By scaffolding larger ambitions onto earlier CBT therapy goals, clients develop continuity between therapy and everyday life. Cognitive behavioral therapy goal setting thus becomes a platform for lifelong development, extending its benefits far beyond symptom reduction or crisis intervention.

7. What role does digital technology play in supporting CBT goal tracking?

The rise of digital mental health tools has greatly enhanced the ability to track progress toward CBT treatment goals. Mobile apps now allow clients to log thought records, mood fluctuations, and exposure tasks in real time, providing a richer picture of their psychological trajectory. These platforms often incorporate reminders, visual progress charts, and customizable features that align with specific cognitive therapy goals. For therapists, such data supports more precise tailoring of interventions. When used judiciously, technology strengthens the feedback loop that makes cognitive behavioral therapy goal setting responsive and dynamic rather than static or linear.

8. How do CBT goals examples vary between adolescents and adults?

Developmental stage plays a critical role in shaping appropriate CBT goals examples. Adolescents, for instance, may focus more on school performance, peer relationships, or self-identity issues. Their goals in CBT often incorporate parental involvement, structure around academic stressors, and developmentally appropriate behavioral targets. Adults, on the other hand, may prioritize career stability, parenting challenges, or relationship dynamics. The principles of cognitive behavioral therapy treatment goals remain the same, but the content, framing, and contextual demands differ. Therapists must adapt their language and expectations accordingly to ensure engagement across age groups.

9. How do cognitive behavioral therapy treatment goals contribute to relapse prevention?

CBT treatment goals are instrumental in relapse prevention because they help clients build awareness of early warning signs and maintain effective coping strategies. By reflecting on the behaviors and thoughts that signaled prior episodes of distress, clients can proactively create action plans rooted in their original goals. For example, a person who has completed CBT for panic disorder may develop a maintenance plan that includes continued practice of breathing techniques and gradual exposure. These are not new goals in CBT—they are extensions of previously achieved milestones. Embedding relapse prevention within the structure of cognitive behavioral therapy goal setting ensures that therapy continues to serve the client even after it ends.

10. What are some common mistakes therapists make when defining CBT therapy goals?

One frequent error is setting goals that are too broad, such as “reduce anxiety,” without clarifying how success will be measured behaviorally. Another mistake involves imposing goals on the client rather than co-developing them, which can undermine motivation and autonomy. Sometimes, therapists also fail to revisit and revise cognitive behavioral therapy treatment goals, treating them as static instead of evolving with the client’s progress. Over-reliance on standardized cbt goals examples without adapting them to the client’s unique situation can also limit relevance. A skilled clinician recognizes that the most effective goals in CBT are those that feel both personally meaningful and strategically grounded in evidence-based methods.

Reflecting on the Transformative Power of CBT Treatment Goals

Cognitive behavioral therapy treatment goals are far more than clinical formalities—they are transformative tools that bridge intention and action, aspiration and achievement. By translating abstract emotional suffering into tangible, achievable objectives, CBT offers clients a way to reclaim their sense of agency and direction. Whether through reducing anxiety, managing depression, or reshaping identity after trauma, goal setting in CBT illuminates a path forward that is both evidence-based and deeply personal.

In this light, cognitive behavioral therapy goal setting is not a one-time task, but a dynamic, evolving practice that adapts to the client’s growth. It fosters clarity, motivation, and accountability while ensuring that therapy remains grounded in outcomes that truly matter. For clinicians and clients alike, these goals are not merely markers of progress—they are signposts of transformation, resilience, and renewed purpose.

Further Reading:

What Are The Goals Of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy?