The Essential Role of Sleep in Brain Function and Memory Formation

Lack of sleep can indeed cause significant memory problems, as sleep is not merely a passive state but a crucial period for the brain’s maintenance and consolidation processes. Sleep plays a vital role in supporting both short-term cognitive functions and long-term brain health. Insufficient sleep disrupts the brain’s ability to encode, consolidate, and retrieve memories effectively. Research indicates that adequate sleep is essential for memory retention, particularly in activities requiring focus, learning, and complex problem-solving. During stages such as slow-wave sleep and REM (rapid eye movement) sleep, the brain processes information, integrates new knowledge, and links it with existing memories. These functions are critical not only for academic achievements but also for emotional balance and overall cognitive performance.

One of the most compelling lines of evidence comes from research using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which demonstrates reduced activity in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex in sleep-deprived individuals. These regions are intimately involved in memory formation and executive function. The hippocampus, in particular, is essential for converting short-term memories into long-term storage, and it is during sleep—especially slow-wave sleep—that this transfer occurs. When individuals are deprived of adequate rest, this delicate neural choreography is disrupted, leading to lapses in memory and difficulty concentrating. Understanding that getting enough sleep for memory retention is not merely helpful but neurologically essential helps reframe how we view sleep—not as a luxury, but as a biological necessity for brain function.

Further emphasizing this point, longitudinal studies have correlated chronic sleep deprivation with both structural and functional changes in the brain. Over time, individuals with poor sleep habits tend to show a reduction in gray matter volume in regions related to memory and cognition. This raises critical concerns not only about day-to-day functioning but also about long-term cognitive health. In a society that often glorifies productivity at the expense of rest, these findings underscore a profound paradox: sacrificing sleep to gain more hours of wakeful output may, in fact, erode the very cognitive faculties that support performance. By understanding the direct connection between sleep and memory processes, we can begin to prioritize rest as a cornerstone of cognitive longevity rather than a negotiable aspect of wellness.

You may also like: What to Eat to Boost Memory: Science-Backed Brain Foods That Improve Recall, Focus, and Long-Term Mental Health

How Sleep Deprivation Disrupts Cognitive Processing and Memory Encoding

Sleep deprivation doesn’t simply make you feel tired—it has measurable effects on how the brain processes information. A growing body of neuroscience research indicates that sleep loss undermines synaptic plasticity, a fundamental mechanism through which the brain encodes experiences into memories. When we are sleep-deprived, our brains become less effective at forming new neural connections, which directly impairs our ability to learn and remember. Numerous studies have sought to answer the question, “Does sleep deprivation cause memory problems?” The overwhelming consensus is yes: even a single night of restricted sleep can hinder memory consolidation and decision-making. Individuals are more prone to errors, less able to focus, and show impaired judgment—all of which are tied to the brain’s reduced capacity to process new information under conditions of fatigue.

The hippocampus, one of the brain’s primary memory centers, becomes less responsive during periods of sleep deprivation. This is particularly concerning given the hippocampus’s role in spatial navigation, working memory, and the conversion of short-term memories into long-term ones. When asked, “Will lack of sleep cause memory loss?” scientists caution that while short-term memory lapses from one poor night of sleep may not equate to permanent damage, chronic deprivation can indeed lead to sustained cognitive impairment. Functional imaging studies confirm that not only is hippocampal activity diminished during tasks involving memory recall in sleep-deprived individuals, but the brain also compensates by increasing activity in other regions, such as the parietal lobes. This compensatory mechanism suggests that the brain is attempting to work around its deficits, which is unsustainable over time.

In addition to cognitive disruption, emotional regulation also suffers when sleep is compromised. The amygdala, a brain region involved in processing emotions, becomes hyperactive during sleep deprivation, while connectivity with the prefrontal cortex—responsible for rational thought and impulse control—is weakened. This dysregulation makes it harder to manage stress and increases vulnerability to anxiety and depression, both of which can further impair memory. Thus, when we ask whether lack of sleep causes memory problems, we must consider a broader framework that includes not just cognitive processing, but emotional stability, stress response, and even metabolic function. The interplay between sleep and memory is not linear but multifaceted, influencing nearly every aspect of brain health.

Chronic Sleep Deprivation and the Risk of Long-Term Memory Impairment

While the cognitive effects of a single night of poor sleep are well documented, the consequences of chronic sleep deprivation are even more profound and concerning. When sleep deprivation becomes a habitual pattern, it can lead to enduring changes in brain structure and function. Researchers have long investigated the question, “Can lack of sleep cause memory problems?” In the context of chronic sleep loss, the answer extends beyond short-term forgetfulness. Prolonged insufficient sleep has been associated with increased beta-amyloid accumulation—a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease—and neuroinflammation, both of which are implicated in neurodegenerative disorders. Therefore, sleep is not only protective in the present moment but may also serve a preventive role against long-term cognitive decline.

In aging populations, the correlation between poor sleep and cognitive decline becomes even more striking. Older adults who suffer from sleep fragmentation or reduced REM sleep tend to perform worse on tests of memory and executive function compared to their well-rested peers. This has led scientists to explore whether sleep disturbances are a precursor to dementia or a symptom of it—or potentially both. The concern that sleep deprivation memory problems could evolve into more serious conditions like dementia is supported by longitudinal cohort studies that show sleep-deprived individuals are more likely to develop mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a potential precursor to Alzheimer’s. This suggests that ensuring proper sleep hygiene throughout life is not only beneficial for daily functioning but may also be neuroprotective over time.

Another key dimension of this issue involves the body’s stress-response system, specifically the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Chronic sleep deprivation elevates cortisol levels, which can damage the hippocampus and reduce neurogenesis—the birth of new neurons. This contributes to what researchers term “lack of sleep memory impairment,” a condition characterized by reduced recall, diminished verbal fluency, and slower cognitive processing. Importantly, this is not limited to older adults. College students, shift workers, and new parents—populations known for inconsistent sleep schedules—often report experiencing these symptoms. Therefore, when we examine whether lack of sleep causes memory loss, we must consider how systemic, long-term sleep deficits may slowly but decisively degrade our mental faculties. The evidence paints a clear picture: to protect memory and cognition, sleep must be prioritized as seriously as nutrition, exercise, or mental stimulation.

The Bidirectional Relationship Between Sleep and Mental Health

The relationship between sleep and mental health is bidirectional: poor sleep can exacerbate psychological issues, and psychological issues can, in turn, disrupt sleep. This complex interplay has significant implications for memory function, particularly in the context of mood disorders like depression and anxiety. Studies have consistently shown that people with insomnia are at a higher risk for developing mental health conditions, while those with existing disorders often experience fragmented or insufficient sleep. The consequences are manifold. Not only does this cycle intensify symptoms of psychological distress, but it also contributes to cognitive decline, raising important questions such as, “Can sleep deprivation cause memory loss?” The scientific community continues to explore this relationship, recognizing that treating sleep disturbances may play a key role in managing mood disorders and preserving cognitive function.

Disruptions in sleep architecture—such as reduced time spent in slow-wave sleep or REM sleep—can interfere with emotional memory consolidation. These stages are crucial for processing and integrating emotional experiences, and when they are disrupted, individuals may struggle with emotional regulation and memory retrieval. This adds another layer to our understanding of how sleep deprivation memory problems manifest in real-world contexts. It’s not just that tired people are forgetful; rather, their ability to integrate emotional experiences into coherent memory narratives is impaired, which can influence personal identity, decision-making, and relationships. Thus, when individuals wonder if lack of sleep causes memory problems, they are often experiencing the emotional as well as cognitive consequences of sleep loss.

Importantly, recent advances in cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) have shown that improving sleep quality can enhance not only mental health outcomes but also memory performance. These findings underscore the possibility that addressing sleep disturbances may mitigate symptoms of mental illness and protect against memory degradation. This further emphasizes the value of getting enough sleep for memory retention, especially in populations vulnerable to psychological distress. The therapeutic implications are far-reaching: by integrating sleep-focused interventions into mental health treatment plans, clinicians may help safeguard both emotional well-being and long-term cognitive integrity. Sleep is no longer viewed merely as a symptom of mental illness, but as a potential therapeutic target in its own right.

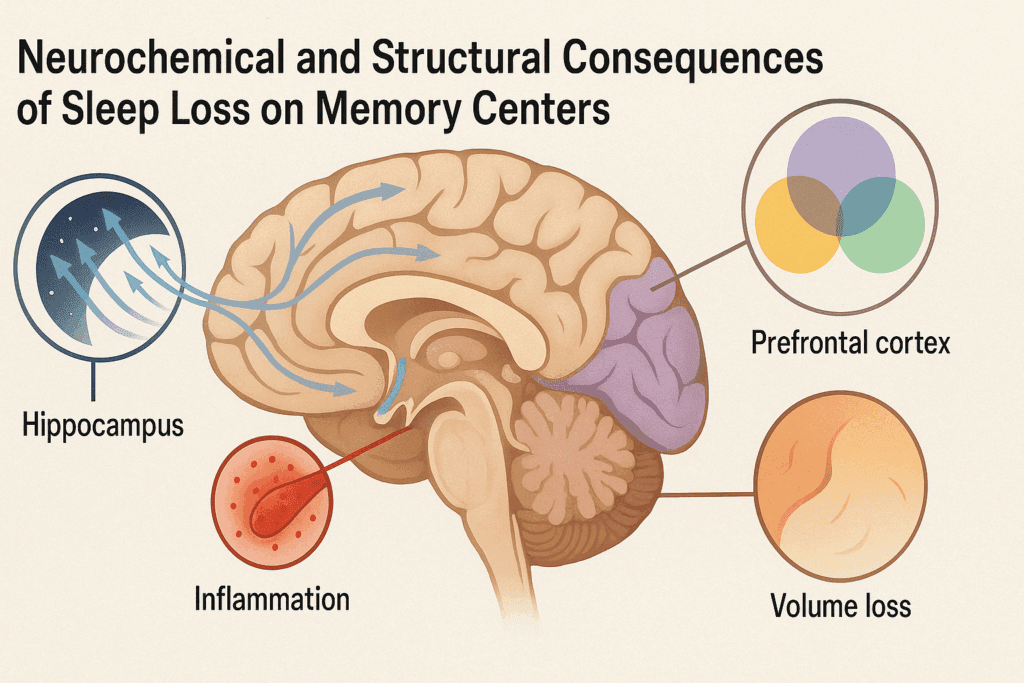

Neurochemical and Structural Consequences of Sleep Loss on Memory Centers

Sleep is an orchestrated neurochemical process that plays a central role in regulating brain function, particularly in memory networks. When sleep is disrupted, the neurochemical balance of the brain becomes disturbed, affecting neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine, serotonin, and dopamine—all of which are integral to memory formation and mood regulation. Disruptions in these chemical messengers provide insight into how and why sleep deprivation memory problems develop. For instance, reductions in acetylcholine during sleep deprivation are associated with impaired attention and difficulty forming new memories, while serotonin imbalances can contribute to emotional dysregulation and depressive symptoms. These neurochemical shifts provide a molecular foundation for understanding how sleep loss can lead to functional deficits.

In addition to neurochemistry, structural brain changes are increasingly being observed in individuals who experience chronic sleep deprivation. Advanced neuroimaging techniques reveal that prolonged sleep loss can lead to volume reductions in the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and other regions associated with executive function and memory consolidation. This raises further concerns regarding questions like, “Does lack of sleep cause memory loss?” The correlation between reduced hippocampal volume and memory performance has been well established, and sleep-related atrophy may contribute to accelerated cognitive aging. Moreover, sleep deprivation elevates inflammatory markers such as interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein, which are known to have neurotoxic effects when chronically elevated.

Another fascinating aspect of this discussion is the concept of “glymphatic clearance,” a process by which the brain clears out waste products during sleep. This system is particularly active during deep sleep and is essential for flushing out neurotoxins like beta-amyloid. When individuals do not get enough restorative sleep, this clearance process is impaired, which could contribute to the accumulation of harmful proteins associated with neurodegenerative diseases. The implication is that getting enough sleep for memory retention is not only about strengthening cognitive functions but also about maintaining the physical health of the brain’s infrastructure. As research continues to uncover the intricate links between sleep and neurobiology, the case for prioritizing sleep as a tool for cognitive preservation becomes stronger than ever.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ): Sleep, Memory, and Long-Term Brain Health

1. How quickly can memory issues develop after losing sleep for just one night?

Even a single night of poor sleep can disrupt your brain’s ability to encode new memories. Most people think memory loss only develops after prolonged sleep deprivation, but even one restless night can impair attention, reaction time, and learning capacity the next day. This raises concerns for students, healthcare workers, and shift employees who often operate with minimal rest. Although this doesn’t constitute permanent damage, it highlights how easily sleep deprivation memory problems can begin. Over time, repeating this cycle can lead to deeper cognitive disturbances, suggesting that even short-term loss of sleep has consequences for memory function.

2. What are some overlooked lifestyle factors that worsen sleep-related memory issues?

Besides the obvious culprits like caffeine and screen exposure, subtle factors such as inconsistent meal timing and inadequate daylight exposure can worsen lack of sleep memory loss. The brain relies on circadian rhythm cues to regulate both sleep and memory consolidation processes. Irregular routines throw off this biological clock, intensifying the effects of sleep deprivation memory problems. Individuals who frequently alter their bedtime or skip breakfast may unknowingly be worsening the potential for long-term cognitive disruption. Addressing these underappreciated influences can mitigate the impact of sleep-related memory impairments.

3. Are younger adults more resilient to memory problems caused by lack of sleep?

It’s a common belief that younger people bounce back more easily from sleep loss, but this doesn’t fully shield them from cognitive consequences. While younger brains may show temporary compensatory mechanisms, repeated episodes of inadequate rest still result in memory deficits. Research suggests that can lack of sleep cause memory problems in young adults just as it does in older populations, especially with chronic patterns. Sleep is vital for memory formation at every age, and recurring disruptions in early adulthood may lay the groundwork for future issues. Prioritizing sleep in youth could therefore be an important strategy to prevent long-term memory decline.

4. How does stress interact with sleep deprivation to affect memory?

Stress and sleep deprivation form a dangerous feedback loop. High stress levels increase cortisol, a hormone that impairs the hippocampus—your brain’s memory hub—especially when combined with poor sleep. This dual assault raises the risk of both emotional and memory-related dysfunction. In this context, does lack of sleep cause memory problems becomes a layered question. Yes, but especially so when compounded by chronic stress. This means reducing stress through mindfulness or cognitive-behavioral strategies may offer indirect protection against sleep-related memory deterioration.

5. Can improving sleep reverse existing memory problems?

There is growing evidence that improving sleep quality may help reverse some types of cognitive decline—especially in the early stages. Neuroplasticity allows the brain to reorganize and form new connections, even after setbacks. While does sleep deprivation cause memory loss remains a concern, emerging data shows that cognitive performance can improve with consistent, restorative sleep. Interventions like cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) have shown promise in restoring memory performance. This reinforces the idea that getting enough sleep for memory retention isn’t just preventive—it may also be part of recovery.

6. Are there any brain-boosting supplements that can offset sleep deprivation memory problems?

Although no supplement replaces the benefits of sleep, certain compounds like magnesium, L-theanine, and omega-3 fatty acids may offer modest support. These nutrients help regulate neurotransmitters and reduce inflammation, both of which are crucial when addressing lack of sleep memory impairment. However, they should be used as complementary tools—not crutches—to optimize brain health. People often ask if can sleep deprivation cause memory loss, hoping for a pill-based solution. While these nutrients may enhance resilience, they cannot eliminate the underlying cognitive risks of chronic sleep deprivation.

7. How do sleep disorders like sleep apnea contribute to memory loss?

Conditions like obstructive sleep apnea fragment sleep architecture, reducing time spent in memory-consolidating phases such as REM and deep sleep. This disruption leads to a decline in memory accuracy, processing speed, and recall ability. For individuals with untreated sleep disorders, the question of does sleep deprivation cause memory problems takes on added urgency. In these cases, poor sleep quality—not just quantity—is responsible for cognitive difficulties. Proper diagnosis and treatment of sleep disorders can significantly reduce the impact of sleep-related memory deficits.

8. What long-term cognitive risks do night shift workers face due to disrupted sleep patterns?

Night shift workers are at high risk for chronic sleep deprivation, which alters circadian rhythms and limits exposure to natural light—both crucial for cognitive recovery. Over time, this can lead to persistent lack of sleep memory loss, even when workers try to “catch up” on rest. Studies indicate that does lack of sleep cause memory loss in this population is more than just a theoretical concern—it’s a measurable reality. Memory tests often show poorer results for shift workers compared to their day-working peers. The long-term cognitive cost of shift work underscores the importance of structural interventions, such as rotating shifts and scheduled naps.

9. How can digital technology use before bed worsen memory impairment?

Blue light from digital devices suppresses melatonin, a hormone essential for initiating sleep. Reduced melatonin delays sleep onset and decreases time spent in memory-consolidating sleep stages. When users repeat this behavior nightly, the cumulative impact leads to sleep deprivation memory problems that can affect daily functioning. While people often ask, will lack of sleep cause memory loss, they rarely consider the subtle habits that contribute to it. Limiting screen time an hour before bed and using blue-light filters can significantly support healthier sleep and memory outcomes.

10. What emerging therapies are being developed to counteract memory loss caused by sleep deprivation?

Recent innovations in neuromodulation, such as transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), show potential in enhancing memory functions impaired by poor sleep. Some devices aim to mimic the electrical patterns of slow-wave sleep to boost cognitive resilience. Additionally, AI-driven sleep tracking tools offer personalized insights to optimize sleep timing and efficiency. These advances suggest that while does sleep deprivation cause memory loss remains a concern, technology may soon provide novel ways to mitigate its effects. However, these solutions work best when combined with behavioral changes aimed at getting enough sleep for memory retention.

Conclusion: Prioritizing Sleep for Memory Health and Cognitive Longevity

In an age where multitasking, late-night screen time, and productivity are often worn as badges of honor, the importance of restorative sleep is frequently overlooked. Yet the evidence is clear: Failing to prioritize sleep has measurable, lasting consequences for brain function and memory. The consistent findings across neurological, psychological, and behavioral sciences answer questions like “Does sleep deprivation cause memory problems?” and “Can sleep deprivation cause memory loss?” with a resounding affirmation. The connection is undeniable, both in the short term—through impaired concentration and recall—and over the long term, through structural brain changes and increased risk of cognitive decline.

As we’ve explored, the consequences of insufficient sleep are far-reaching, affecting not only memory but also emotional regulation, stress response, and neurobiological health. Understanding whether lack of sleep causes memory loss is not just an academic question—it has real implications for how we live, work, and age. Whether you’re a student preparing for exams, a professional navigating high-stakes responsibilities, or an older adult striving to preserve cognitive function, getting enough sleep for memory retention is a non-negotiable pillar of health. By recognizing and addressing the risks of sleep deprivation memory problems, individuals can make informed lifestyle choices that promote mental clarity and long-term cognitive vitality.

The path forward involves more than simply sleeping longer—it requires improving sleep quality, addressing underlying health conditions, and reevaluating societal norms that equate sleeplessness with success. It means asking not only “Will lack of sleep cause memory loss?” but also, “What am I doing to protect my brain for the future?” The answer lies in embracing sleep as a fundamental, science-backed strategy for cognitive resilience. In doing so, we not only enhance our memory and productivity today but also build a foundation for mental health and sharpness in the years to come.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out.

Further Reading:

How Lack of Sleep Impacts Cognitive Performance and Focus

How Sleep Deprivation Affects Your Memory

Too little sleep, and too much, affect memory

Disclaimer

The information contained in this article is provided for general informational purposes only and is not intended to serve as medical, legal, or professional advice. While Health11News strives to present accurate, up-to-date, and reliable content, no warranty or guarantee, expressed or implied, is made regarding the completeness, accuracy, or adequacy of the information provided. Readers are strongly advised to seek the guidance of a qualified healthcare provider or other relevant professionals before acting on any information contained in this article. Health11News, its authors, editors, and contributors expressly disclaim any liability for any damages, losses, or consequences arising directly or indirectly from the use, interpretation, or reliance on any information presented herein. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of Health11News.