In recent years, the connection between physical activity and brain health has garnered substantial attention, particularly as rates of dementia rise worldwide. This growing interest is not merely anecdotal. Scientific inquiry is increasingly illuminating the complex, dynamic relationship between physical exercise and cognitive function, offering both hope and evidence-based strategies for those seeking to prevent or manage dementia. Against this backdrop, a critical question has emerged: Can exercise prevent dementia—or even help reverse it? The implications of this inquiry extend far beyond the realms of fitness and neurology; they influence public health policy, clinical practice, and the daily lives of aging populations.

You may also like: How to Prevent Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease Naturally: Expert-Backed Strategies to Reduce Your Risk Through Lifestyle and Diet

Understanding Dementia and Its Impact on Cognitive Well-Being

Dementia is not a single disease but a general term encompassing various neurological conditions that impair memory, reasoning, and other cognitive abilities. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form, followed by vascular dementia and several other less prevalent types. As the brain deteriorates, individuals experience progressive cognitive decline, often accompanied by emotional and behavioral changes that profoundly impact quality of life.

The global burden of dementia is staggering, with over 55 million people currently affected and projections suggesting a near tripling of cases by 2050. These statistics underscore the urgency of identifying modifiable risk factors. While age, genetics, and certain medical conditions play unavoidable roles, growing evidence points to lifestyle interventions—including physical exercise—as powerful tools in mitigating risk. The recognition of exercise as a potential avenue for cognitive preservation is not merely about slowing decline; it is also about enhancing mental resilience and quality of life for older adults.

How Exercise Impacts the Brain: Mechanisms and Neurobiology

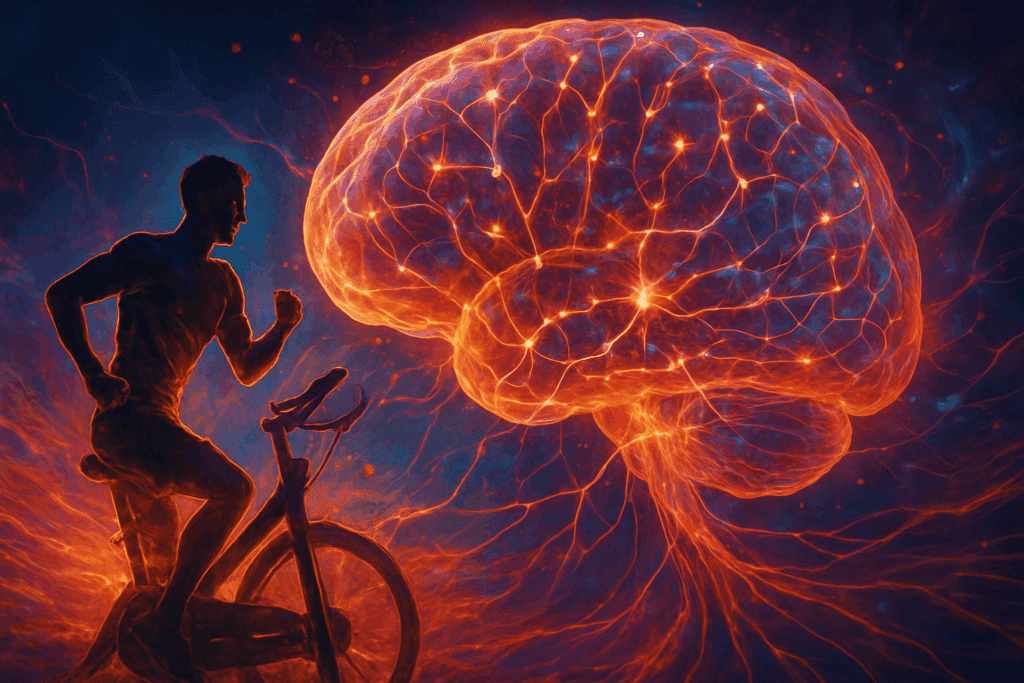

The biological mechanisms through which physical activity supports cognitive health are multifaceted. Exercise stimulates the release of neurotrophic factors such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which plays a key role in promoting neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to reorganize and form new connections. This process is particularly critical in aging populations, where synaptic flexibility becomes essential for maintaining mental acuity.

Additionally, regular physical activity enhances cerebral blood flow, delivering oxygen and nutrients to the brain more efficiently. This increased perfusion contributes to the preservation of gray matter volume in regions associated with memory and executive function, such as the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. Furthermore, exercise exerts anti-inflammatory effects and helps regulate insulin sensitivity, both of which are implicated in cognitive decline. These physiological changes offer compelling support for the idea that engaging in exercise to prevent dementia is not only plausible but also scientifically grounded.

Cardiovascular Fitness and Cognitive Function: A Critical Link

Perhaps one of the most well-documented relationships in dementia prevention is the link between cardiovascular health and cognitive performance. Studies have consistently shown that individuals with better cardiorespiratory fitness exhibit superior cognitive function and a lower risk of developing dementia. This correlation is largely due to the fact that cardiovascular disease and dementia share many common risk factors, including hypertension, diabetes, and obesity.

Aerobic exercises such as brisk walking, cycling, swimming, and running have been particularly effective in promoting both cardiovascular and cognitive health. These activities improve heart function and vascular integrity, thereby reducing the risk of cerebral small vessel disease, a major contributor to vascular dementia. In this context, implementing a regular aerobic routine serves not only to enhance general physical health but also to foster the protective benefits of exercise to prevent dementia.

Strength Training and Neurocognitive Benefits

While aerobic activity often takes center stage in discussions about brain health, resistance training also offers unique cognitive benefits. Strength training has been shown to improve executive functions such as attention, decision-making, and problem-solving—skills that are crucial for maintaining independence in older age. This form of exercise may also contribute to structural brain changes, including increased cortical thickness and improved white matter integrity.

Importantly, strength training supports metabolic health by improving glucose regulation and reducing insulin resistance, factors that have been closely linked to neurodegenerative conditions. Furthermore, resistance exercises can help maintain muscle mass and reduce frailty, thereby lowering the risk of falls and hospitalization—events that are often associated with accelerated cognitive decline in older adults. Thus, while aerobic activity forms the foundation, incorporating resistance training enhances the multidimensional benefits of using exercise to prevent dementia.

Exercise and Mild Cognitive Impairment: Early Intervention Strategies

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is often considered a transitional state between normal aging and dementia. Individuals with MCI may experience subtle changes in memory and thinking skills that are noticeable but not severe enough to interfere significantly with daily life. Identifying and intervening during this stage is crucial, as it represents a window of opportunity to delay or possibly prevent progression to dementia.

A growing body of research suggests that exercise can be particularly effective in this early phase. Clinical trials have shown that individuals with MCI who engage in structured exercise programs demonstrate improvements in cognitive performance, particularly in areas such as working memory, processing speed, and executive function. These findings raise an important question: can exercise reverse dementia, or at least halt its progression during the MCI phase? While full reversal may be elusive, the stabilization and enhancement of cognitive function are achievable goals that carry profound significance.

The Role of Lifestyle Integration and Behavioral Adherence

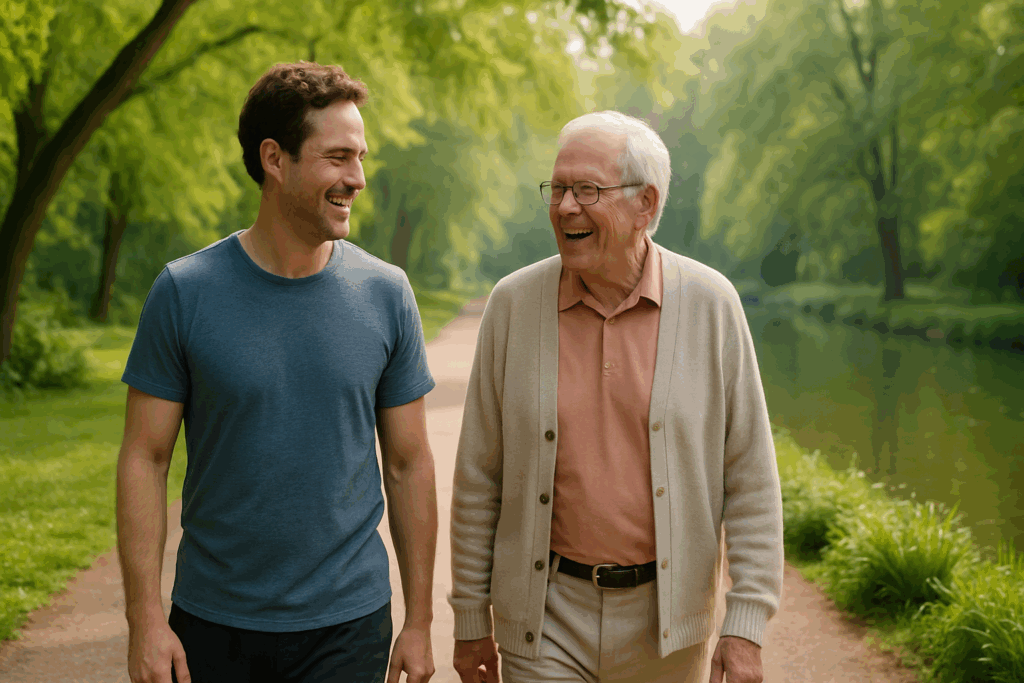

For exercise to yield cognitive benefits, consistency and long-term adherence are essential. Sporadic activity is unlikely to produce lasting neurological effects. Therefore, integrating exercise into daily routines and promoting behavioral adherence become critical components of dementia prevention strategies. Motivation, social support, and personalized goal-setting are key factors that influence engagement in physical activity, especially among older adults.

Programs that combine physical activity with social interaction—such as group fitness classes or walking clubs—not only enhance adherence but also provide added mental health benefits by reducing loneliness and depression, both of which are associated with increased dementia risk. Encouragingly, even moderate levels of physical activity can be effective, highlighting the importance of tailoring programs to individual capabilities and preferences. This inclusive approach reinforces the feasibility of leveraging exercise to prevent dementia across diverse populations.

Can Exercise Reverse Dementia? Analyzing the Current Evidence

The notion that exercise might reverse dementia remains a complex and nuanced question. While there is strong evidence supporting the preventive benefits of physical activity, claims of reversal must be approached with caution. Dementia, particularly in its later stages, involves irreversible structural brain changes, including significant neuronal loss and atrophy. Therefore, the term “reversal” should not be interpreted as a cure but rather as a means to slow progression, improve symptoms, and enhance quality of life.

Nonetheless, several studies have reported promising results. For example, individuals with early-stage dementia who participated in high-intensity aerobic or multimodal exercise programs exhibited improvements in memory, attention, and mood. These changes were often accompanied by enhanced functional connectivity within the brain, suggesting that exercise may partially restore certain neural networks. While more research is needed to determine the long-term effects and optimal protocols, these findings contribute to the growing belief that using exercise to prevent dementia may extend to therapeutic contexts as well.

Exercise Prescription: Guidelines for Cognitive Health

When prescribing exercise for cognitive health, the type, intensity, frequency, and duration all matter. Current guidelines recommend at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity per week, combined with two or more days of muscle-strengthening activities. These recommendations serve as a general foundation, but they can be adapted based on individual health status, preferences, and functional capacity.

Incorporating variety—such as combining aerobic, resistance, balance, and flexibility exercises—offers comprehensive benefits that extend beyond cognitive function to overall well-being. Activities like tai chi and yoga, which integrate movement with mindfulness, have also demonstrated positive effects on attention and stress regulation. By creating a holistic and personalized exercise plan, individuals can maximize the protective and restorative potential of physical activity on brain health.

Public Health Implications and the Path Forward

The widespread adoption of exercise as a preventive and therapeutic tool for cognitive health carries profound implications for public health systems. Implementing community-based programs that promote physical activity among older adults can reduce the societal burden of dementia, lower healthcare costs, and improve quality of life on a population level. These initiatives should be culturally sensitive, accessible, and inclusive, ensuring that barriers related to mobility, socioeconomic status, and health literacy are addressed.

Healthcare providers also play a critical role by incorporating exercise counseling into routine care, particularly for patients at risk of cognitive decline. Education and training for clinicians on the cognitive benefits of exercise can facilitate more proactive discussions and empower patients to take control of their brain health. As the evidence base continues to grow, integrating exercise into standard dementia care pathways may become an essential component of comprehensive neurocognitive wellness.

Innovative Research and Emerging Frontiers

Ongoing research continues to explore how exercise interacts with other modifiable factors such as diet, sleep, stress, and cognitive training. Emerging studies suggest that multimodal interventions—those combining physical activity with cognitive stimulation and nutritional support—may offer synergistic benefits for brain health. These integrative approaches hold promise for creating personalized, precision-based strategies to optimize cognitive aging.

Advancements in neuroimaging and biomarker analysis are also shedding light on how different types of exercise affect brain structure and function. For instance, diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and functional MRI (fMRI) are helping scientists visualize the ways in which exercise enhances connectivity within critical brain networks. As our understanding of these mechanisms deepens, we may move closer to identifying the most effective exercise protocols for delaying or even partially reversing cognitive decline.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. How soon should one start exercising to gain protective benefits against dementia?

The ideal time to start exercising to prevent dementia is as early as possible, preferably in midlife, when many risk factors for cognitive decline begin to emerge. Studies suggest that engaging in regular physical activity in one’s 40s and 50s may provide a neurological buffer that supports cognitive resilience later in life. However, it’s never too late to begin. Even individuals in their 60s or older can experience cognitive benefits from consistent movement. While the question “can exercise reverse dementia” has complex answers, starting earlier significantly increases the odds of slowing or stalling neurodegenerative processes before irreversible damage sets in.

2. What types of exercise are best for stimulating neuroplasticity in the aging brain?

Exercises that engage both the body and mind—like dance, martial arts, or complex movement patterns—tend to be particularly effective in enhancing neuroplasticity. These activities require coordination, rhythm, and often memory recall, which help stimulate regions of the brain beyond those activated by repetitive aerobic movements. While aerobic routines remain a cornerstone of strategies that use exercise to prevent dementia, layered or cognitively demanding exercises may offer an added neurocognitive boost. Emerging research is also exploring the synergistic impact of combining physical activity with cognitive training to further enhance brain connectivity. Such multifaceted routines may one day become the standard prescription for age-related cognitive preservation.

3. Can exercise reverse dementia symptoms once they’ve already appeared?

The idea that exercise can reverse dementia is still being studied and remains somewhat controversial. While it’s unlikely that physical activity can reverse late-stage dementia, there’s growing evidence that certain symptoms—such as confusion, agitation, or mood disturbances—can be alleviated with regular movement. In early-stage dementia, physical activity may help preserve neural networks and slow deterioration. In some cases, cognitive performance has been seen to improve modestly, particularly in areas like attention span and working memory. Therefore, while we cannot yet say that exercise reverses dementia in a clinical sense, it remains a powerful tool in managing its progression and improving quality of life.

4. How does exercise interact with other therapies used for cognitive decline?

Exercise complements traditional and alternative therapies, often enhancing their effectiveness. For instance, physical activity improves sleep quality, which in turn supports memory consolidation. Exercise to prevent dementia may also boost the efficacy of medications by improving vascular health and reducing inflammation. Additionally, when paired with cognitive behavioral therapy or mindfulness-based interventions, exercise can reduce stress hormones that negatively impact brain function. As the question “can exercise reverse dementia” gains more attention, multidisciplinary approaches that include physical movement as a pillar of treatment are likely to become the gold standard for cognitive care.

5. Are there specific exercise routines tailored for people already diagnosed with mild to moderate dementia?

Yes, tailored exercise programs are increasingly being developed for individuals at various stages of cognitive decline. These routines typically emphasize safety, balance, and simplicity while incorporating rhythmic and repetitive movements that are easy to follow. When designed carefully, such programs can provide not only physical benefits but also reduce anxiety, foster social interaction, and encourage daily structure. Using exercise to prevent dementia is often part of these routines, but adaptations make them accessible even after a diagnosis. Importantly, caregivers should be involved in helping implement these plans, ensuring that individuals remain both motivated and safe.

6. What role does social engagement during physical activity play in brain health?

The social component of exercise can significantly amplify its cognitive benefits. Group fitness classes, walking clubs, or dancing sessions provide not just movement but also meaningful interpersonal connection. Social isolation is a known risk factor for cognitive decline, and combining exercise with social engagement creates a powerful synergy. Programs that include social dynamics are especially relevant when considering how exercise to prevent dementia can be made more sustainable and enjoyable. In environments where people feel supported and connected, they are more likely to maintain their routines, thereby increasing the long-term cognitive advantages.

7. Is high-intensity exercise more effective than moderate activity for protecting cognitive function?

There’s an ongoing debate about the optimal intensity for cognitive protection. High-intensity interval training (HIIT) has shown promising results in boosting executive function and memory recall in some studies, especially among younger and middle-aged adults. However, moderate-intensity aerobic exercise, such as brisk walking or swimming, remains the most accessible and widely studied method for using exercise to prevent dementia. Importantly, consistency appears to be more crucial than intensity. For older adults or those with limited mobility, regular low-impact movement is far better than sporadic bursts of vigorous activity. Long-term engagement is the key, regardless of intensity.

8. Can wearable fitness technology help older adults use exercise to prevent dementia?

Absolutely, wearable devices can play a transformative role in promoting brain health through movement. Tools like smartwatches, step counters, and heart rate monitors offer real-time feedback and allow users to track progress, set goals, and stay motivated. For seniors, these technologies can also detect falls, monitor sleep, and encourage consistent daily routines—all of which contribute to cognitive stability. By providing tangible metrics, wearable tech adds a gamification element that supports behavioral adherence. While technology alone cannot answer the question of whether exercise can reverse dementia, it certainly empowers individuals to adopt preventive habits more effectively.

9. How do cultural and socioeconomic factors influence access to exercise-based dementia prevention?

Access to safe spaces for exercise, financial resources for fitness programs, and culturally relevant wellness initiatives all play critical roles in enabling individuals to use exercise to prevent dementia. Communities that lack parks, walkable streets, or recreational centers may find it more challenging to engage in regular activity. Furthermore, language barriers, health literacy, and cultural beliefs about aging and movement can affect participation rates. To broaden the impact of dementia prevention efforts, public health initiatives must address these disparities by creating inclusive and equitable opportunities for physical engagement. Only then can the full potential of lifestyle-based prevention be realized across diverse populations.

10. What future advancements might enhance our ability to use exercise to prevent or treat dementia?

As research evolves, personalized exercise prescriptions based on genetic, metabolic, and cognitive profiles may become standard in dementia prevention. Emerging technologies like virtual reality are already being tested in rehabilitation settings, offering immersive environments that promote both movement and mental stimulation. Artificial intelligence could one day help customize programs by predicting which types of activity best suit an individual’s brain health needs. Additionally, integrative models that combine physical activity with dietary, pharmacological, and psychological therapies are being developed. Although the question “can exercise reverse dementia” continues to spur research, the convergence of innovation and science suggests that future strategies may offer more targeted and impactful results than ever before.

Conclusion: The Powerful Role of Physical Activity in Preventing and Potentially Reversing Dementia

In light of the current evidence, it is clear that physical activity serves as a cornerstone of cognitive health, particularly as individuals age. Whether through its effects on neuroplasticity, cardiovascular integrity, or mental resilience, the role of exercise to prevent dementia is both scientifically substantiated and practically accessible. While the question “can exercise reverse dementia” remains complex, the available data suggest that physical activity can indeed slow progression, improve symptoms, and enhance quality of life—especially when initiated early and maintained consistently.

Crucially, the value of exercise extends beyond individual benefits; it represents a scalable, cost-effective, and universally available strategy for addressing one of the most pressing public health challenges of our time. As research continues to evolve, a multidimensional approach that includes physical activity, dietary optimization, social engagement, and cognitive training will likely offer the most robust defense against cognitive decline.

Empowering individuals with the knowledge and tools to prioritize movement in their daily lives is not just a recommendation—it is a call to action. In the pursuit of healthy aging and sustained mental vitality, exercise is not merely an option; it is an imperative. Through informed choices and collective effort, we can shape a future where cognitive health is protected, dementia risk is minimized, and the aging brain is supported with both science and intention.

Further Reading:

Physical Exercise as a Preventive or Disease-Modifying Treatment of Dementia and Brain Aging

Lifelong exercise linked to lower dementia risk

Physical exercise in the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease