Dementia is far more than a memory disorder—it often brings with it an emotional storm of agitation, irritability, aggression, and even hallucinations that profoundly disrupt both the patient’s daily life and the lives of their caregivers. As neurodegeneration progresses, behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) emerge in up to 90% of patients, making the treatment of these symptoms one of the most pressing challenges in dementia care. Families and clinicians alike are left searching for answers to emotionally charged questions: What is the best sedative for dementia patients experiencing severe agitation? Which medication for dementia agitation provides relief without undue side effects? And what is the best anxiety medication for dementia patients whose fear and confusion spiral into aggression?

In this in-depth article, we explore expert-backed strategies for managing agitation, irritability, and hallucinations in elderly individuals with dementia. Drawing from geriatric psychiatry, neurology, and pharmacology, we investigate the nuanced use of psychotropic medications—best medications for elderly patients such as cholinesterase inhibitors (Donepezil, Rivastigmine), SSRIs (Sertraline, Citalopram), and atypical antipsychotics (Risperidone, Quetiapine)—their benefits, risks, and the science behind their selection. From questions like “is Aricept an antipsychotic?” to concerns about the best med for hallucinations for elderly patients, our aim is to present a clear, research-informed guide that helps caregivers and clinicians navigate the complex terrain of behavioral symptoms in dementia.

You may also like: How to Prevent Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease Naturally: Expert-Backed Strategies to Reduce Your Risk Through Lifestyle and Diet

Understanding Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms in Dementia

Agitation, irritability, and hallucinations are not simply distressing outliers in dementia—they are core features of the disease’s neuropsychiatric progression. These symptoms can manifest as pacing, verbal outbursts, physical aggression, delusions, or disturbing visual hallucinations. The underlying neurobiology points to disrupted neurotransmitter systems, including serotonin, dopamine, and acetylcholine. Additionally, structural brain changes, such as damage to the frontal and temporal lobes, reduce a person’s ability to regulate mood and behavior.

The management of agitation in dementia is particularly complex due to its multifactorial nature. Triggers often include pain, infections, sensory impairments, or environmental changes. In some cases, delusions or hallucinations may drive the agitation, especially in forms like Lewy body dementia or Parkinson’s disease dementia. Treatment must therefore go beyond a one-size-fits-all approach and instead account for the root causes of the symptoms. In clinical practice, non-pharmacological interventions are typically the first line of defense. However, when these fail, medications become an important—and often necessary—component of the treatment plan.

Why Pharmacological Intervention Is Sometimes Necessary

While psychosocial strategies such as redirection, calming environments, and personalized music therapy are invaluable, they may not be sufficient in cases where behavioral disturbances threaten safety. In such scenarios, clinicians must weigh the risks and benefits of introducing psychotropic medications. The selection of the best med for hallucinations for elderly patients or appropriate drugs for dementia agitation must be done with caution, precision, and an individualized understanding of the patient’s history, sensitivities, and dementia subtype.

Pharmacological treatment of agitation in dementia is not about sedation for its own sake. It is about restoring a degree of calm that allows patients to live with dignity and caregivers to provide consistent support. When agitation escalates to violence, or when hallucinations produce significant distress, it becomes not only ethical but necessary to explore medication for agitation and irritability in dementia that can reduce suffering without diminishing quality of life. It is in these cases that healthcare providers often explore what is the best sedative for dementia patients—balancing efficacy with the goal of maintaining alertness and functionality.

Antipsychotics: Benefits and Cautions

Antipsychotics remain among the most commonly prescribed medications for dementia agitation, though their use is often controversial. Agents such as risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine are sometimes prescribed when hallucinations, paranoia, or extreme aggression compromise patient safety. For those seeking the best med for hallucinations for elderly patients, these drugs may offer relief—particularly in cases of Lewy body or Alzheimer’s disease with psychotic features.

However, antipsychotics come with significant risks. Increased mortality, cerebrovascular events, and extrapyramidal symptoms make their long-term use problematic, especially in frail elderly populations. This has led many clinicians to view their use as a last resort, suitable only after other strategies have failed. Moreover, families often ask, “Is Aricept an antipsychotic?” The answer is no—Aricept (donepezil) is a cholinesterase inhibitor used to enhance cognitive function, not to manage psychosis or agitation.

Despite the risks, antipsychotics can be lifesaving tools in acute crises. When selecting among the drugs for dementia agitation, clinicians typically choose medications with the lowest effective dose and a clearly defined endpoint for reassessment. This cautious, case-by-case approach to the treatment of agitation in dementia ensures that pharmacological intervention supports, rather than replaces, human-centered care.

The Role of Antidepressants in Treating Agitation and Irritability

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have emerged as a potentially safer alternative to antipsychotics for managing mood-related symptoms. Medications such as sertraline and citalopram have shown moderate effectiveness in the treatment of agitation in dementia, particularly when irritability and anxiety are prominent. Their delayed onset of action—typically several weeks—requires patience, but their improved safety profile makes them a compelling option.

Patients with vascular dementia or Alzheimer’s disease may present with overlapping depressive symptoms that contribute to behavioral disturbances. In these scenarios, identifying what is the best anxiety medication for dementia patients often leads to a discussion of SSRIs, especially when non-sedating relief from emotional distress is needed. Importantly, these medications may also mitigate insomnia and appetite changes, which can exacerbate irritability.

While SSRIs are not without side effects—such as hyponatremia or gastrointestinal discomfort—they are less likely than antipsychotics to cause sedation, movement disorders, or cardiovascular complications. Thus, they represent an important class of medication for dementia agitation, especially when used as part of a broader treatment strategy that includes environmental adjustments and caregiver training.

Mood Stabilizers and Anticonvulsants: When They Are Used and Why

Beyond antidepressants and antipsychotics, some clinicians turn to anticonvulsants such as valproic acid or carbamazepine in an attempt to calm severe behavioral disturbances. These agents, commonly used in epilepsy and bipolar disorder, offer mood-stabilizing properties that may be beneficial for dementia patients with impulsivity, aggression, or mood swings. However, the evidence supporting their effectiveness in the management of agitation in dementia remains mixed.

Valproic acid, in particular, has been studied for its use in behavioral symptoms, but concerns about liver toxicity, sedation, and drug interactions have limited its widespread adoption. Nevertheless, in carefully selected patients, especially those who are intolerant to other medications, anticonvulsants may offer an additional line of defense.

It is important to note that these medications are not typically the first choice when considering what is the best sedative for dementia patients. Their sedative effects can be unpredictable, and their benefits often hinge on precise dosing and careful monitoring. That said, their utility in specific contexts—such as in patients with comorbid seizure disorders or bipolar-like symptoms—should not be dismissed outright.

Benzodiazepines: A Double-Edged Sword in Dementia Care

Benzodiazepines such as lorazepam and oxazepam are potent sedatives that can rapidly reduce anxiety and agitation. However, they also carry significant risks, particularly in elderly patients with dementia. Sedation, falls, paradoxical agitation, and dependence are common complications. For this reason, benzodiazepines are generally discouraged for long-term use but may be utilized briefly in acute settings.

Still, there are moments in clinical practice where caregivers or healthcare providers may ask, “What is the happy pill for dementia patients?” This colloquial expression often refers to medications that provide quick mood stabilization, and benzodiazepines are sometimes seen as fitting this description. But experts caution against relying on these medications as a solution for chronic behavioral symptoms.

Instead, when short-term use is deemed necessary—such as during hospitalization, relocation, or acute psychosis—benzodiazepines may be used with extreme care. In such cases, their inclusion in a broader strategy of treating aggression in dementia must be paired with plans for tapering and transition to safer alternatives.

Cholinesterase Inhibitors and Memantine: Cognitive and Behavioral Benefits

Cholinesterase inhibitors like donepezil (Aricept) and rivastigmine are best known for their cognitive effects, but they may also offer modest benefits in managing behavioral symptoms. Although the answer to “Is Aricept an antipsychotic?” is definitively no, some studies suggest that patients who remain on these medications exhibit reduced severity of hallucinations and agitation over time, particularly in Alzheimer’s disease.

Memantine, an NMDA receptor antagonist approved for moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s, also shows promise in reducing aggression and irritability. Its neuroprotective mechanism may stabilize mood and cognition, providing a gentler approach to managing difficult behaviors. When considering medicine for dementia agitation, memantine is often viewed as a low-risk adjunct to other therapies.

These medications are typically well-tolerated and may help delay the need for more potent psychotropics. However, their benefits are modest and should be viewed as part of a long-term management plan rather than an acute intervention for severe agitation or psychosis. Nonetheless, they remain foundational in the treatment landscape, especially when used early and consistently.

Personalized Pharmacological Strategies: Matching Treatment to Symptom Profile

One of the most important aspects of treating agitation in dementia is the personalization of care. Not every patient with hallucinations needs antipsychotics, and not every irritable patient requires sedatives. A detailed clinical evaluation—accounting for medical history, current medications, type and stage of dementia, and specific behavioral symptoms—is critical to selecting the most appropriate drug.

For patients with persistent delusions and hallucinations, especially in Lewy body or Parkinson’s-related dementias, the best med for hallucinations for elderly individuals may be quetiapine due to its lower risk of worsening motor symptoms. For Alzheimer’s patients experiencing paranoia and aggression, a brief trial of risperidone may be warranted. For those with generalized anxiety and irritability, sertraline or citalopram may be considered the best anxiety medication for dementia patients when non-drug strategies have proven insufficient.

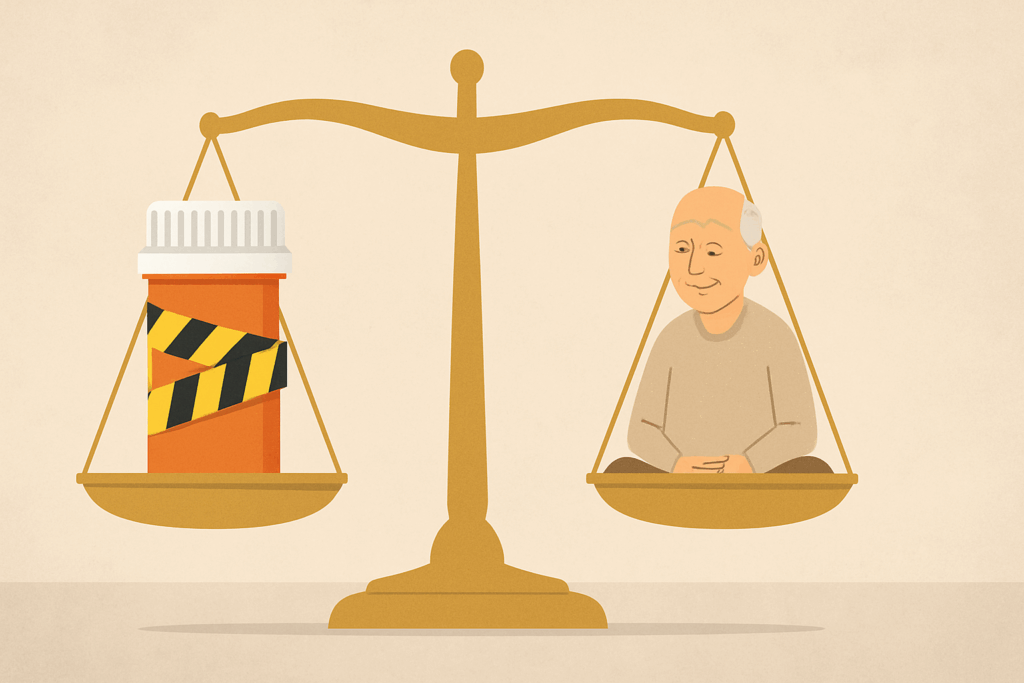

The decision-making process also involves conversations with caregivers about goals of care, tolerability, and quality of life. While medication for dementia agitation can reduce suffering, the risks must always be weighed against the potential for functional decline or adverse effects. This balancing act is central to ethical dementia care.

Ongoing Monitoring and Adjustments: The Dynamic Nature of Dementia Treatment

Dementia is a progressive condition, and the pharmacological needs of patients evolve over time. What once served as an effective medicine for dementia agitation may later become problematic due to declining liver function, increased sedation sensitivity, or drug interactions. This necessitates continual reevaluation of medication regimens, dosage adjustments, and sometimes the discontinuation of once-effective treatments.

Clinicians must remain vigilant for signs of adverse effects, such as worsening confusion, new tremors, or falls. Regular consultations with neurologists, geriatricians, and pharmacists help ensure that drugs for dementia agitation remain both safe and effective. Caregivers, too, play an essential role in reporting changes in behavior or alertness that may suggest a need for reassessment.

In cases where medications are tapered or stopped, the transition should be gradual and closely monitored. The use of behavioral scales, caregiver feedback, and objective measures such as fall risk assessments can guide these decisions. Effective management of agitation in dementia is never static—it requires flexibility, collaboration, and compassion.

The Ethical Dimension: Balancing Safety, Dignity, and Autonomy

Every decision to medicate a dementia patient for behavioral symptoms carries ethical implications. Families and care teams must balance the need to reduce suffering with the imperative to respect patient autonomy and maintain dignity. Questions like “What is the happy pill for dementia patients?” reveal a natural desire to ease distress, but they must be approached with a thoughtful understanding of what that truly entails.

Overmedication remains a concern, especially in long-term care settings. Yet under-treatment can be equally harmful, leaving patients trapped in fear, agitation, or aggression that erodes their relationships and wellbeing. The best outcomes arise when families, clinicians, and caregivers work together to develop treatment plans that are individualized, evidence-based, and guided by empathy.

Informed consent, advance care planning, and honest conversations about goals of care are integral to ethical dementia treatment. The use of medication for agitation and irritability in dementia should always be part of a broader vision for holistic support that includes comfort, communication, and continuity.

Frequently Asked Questions: Medications for Agitation, Irritability, and Hallucinations in Dementia

1. Can medication for dementia agitation worsen cognitive decline over time?

Yes, certain types of medication for dementia agitation may contribute to cognitive slowing or confusion if not carefully selected and monitored. This is particularly true of sedatives and antipsychotics, which can impair attention, memory, and processing speed in elderly patients. When deciding on the best med for hallucinations for elderly individuals or choosing a sedative, healthcare providers weigh cognitive side effects heavily. Newer research emphasizes “start low, go slow” dosing and time-limited trials to reduce these risks. The goal in the treatment of agitation in dementia is always to find the lowest effective dose that achieves stability without sacrificing mental clarity.

2. What is the best sedative for dementia patients with sundowning behavior?

Sundowning presents a unique challenge because symptoms typically intensify in the late afternoon or evening. For this specific presentation, the best sedative for dementia patients may be a low-dose trazodone or melatonin, both of which target sleep-wake rhythm disturbances rather than blunt cognition. These options offer a more physiologically attuned solution compared to benzodiazepines, which, while sedating, can worsen confusion and increase fall risk. Proper lighting, a consistent evening routine, and minimizing stimulants can also support these pharmacologic approaches. When used strategically, medication for agitation and irritability in dementia related to sundowning can be both gentle and effective.

3. How do clinicians determine the best med for hallucinations for elderly patients with different dementia types?

Choosing the best med for hallucinations for elderly patients requires a nuanced understanding of the type of dementia they have. For example, in Lewy body dementia, certain antipsychotics can cause severe motor side effects, making drugs like quetiapine or pimavanserin preferable due to their lower risk profiles. In contrast, Alzheimer’s patients might tolerate risperidone better in the short term for visual hallucinations. Medication for dementia agitation must also consider coexisting delusions, paranoia, or sleep disruption. Personalized medicine—based on neuropsychiatric profiles, physical comorbidities, and past drug responses—is central to making safe choices.

4. Is Aricept an antipsychotic, and can it be used for behavioral symptoms?

No, Aricept (donepezil) is not an antipsychotic—it is a cholinesterase inhibitor approved for treating memory and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. However, some evidence suggests it may indirectly reduce irritability or hallucinations by supporting neurotransmitter balance. While it’s not typically classified as a frontline medicine for dementia agitation, it can be a valuable foundational therapy. In some cases, patients on Aricept experience fewer behavioral disturbances over time, possibly reducing the need for stronger medications. Nonetheless, when behavioral symptoms become acute, additional drugs for dementia agitation are often needed alongside cognitive agents.

5. What is the happy pill for dementia patients, and is there a safe version of it?

The term “happy pill” is a colloquial expression often used to describe a drug that lifts mood or calms behavior. In dementia care, this might refer to SSRIs like sertraline or citalopram, which can alleviate chronic irritability, anxiety, or mild depression. While not a medical term, understanding what is the happy pill for dementia patients can help families and caregivers seek out medications that enhance emotional stability without heavy sedation. Importantly, safety is always prioritized; many clinicians now avoid older sedatives and prefer antidepressants with fewer cognitive side effects. Used thoughtfully, such medications support both patient well-being and caregiver peace of mind.

6. Can medications for agitation and irritability in dementia be used during hospitalizations or surgeries?

Yes, but with important precautions. Hospital environments can intensify behavioral symptoms in dementia due to unfamiliarity, sensory overload, and disrupted routines. In these cases, short-term use of medication for agitation and irritability in dementia—often low-dose antipsychotics or sedatives—can help ensure safety and cooperation. However, drug choice is critical: elderly patients are more sensitive to delirium and oversedation, especially postoperatively. Collaboration with geriatric specialists ensures that treatment of agitation in dementia during hospital stays is safe, minimally invasive, and reversible. Non-drug strategies, like familiar objects and continuity of care, are also essential supports.

7. How does treating aggression in dementia differ from managing general agitation?

Treating aggression in dementia often involves a more urgent clinical response, especially if the behavior risks harm to others or the patient themselves. While general agitation might be addressed through calming routines or gentle redirection, physical aggression typically warrants a stronger therapeutic approach. In such cases, drugs for dementia agitation with faster onset—like risperidone or lorazepam—may be considered under close supervision. The key is determining the root cause of aggression, which might include pain, fear, or delusions. Effective management of agitation in dementia must always consider whether the behavior is reactive, psychotic, or environmental in origin.

8. What is the best anxiety medication for dementia patients who also have cardiovascular conditions?

This is a critical consideration because many dementia patients also have comorbid heart disease or stroke risk. The best anxiety medication for dementia patients with cardiovascular concerns is often sertraline, which has a relatively safe cardiac profile. Avoiding tricyclic antidepressants and high-potency antipsychotics is important, as these can cause arrhythmias or blood pressure fluctuations. Medicine for dementia agitation in this population must be carefully selected to avoid adverse drug interactions and vascular side effects. Non-pharmacological interventions like guided imagery or therapeutic touch should also be incorporated to minimize medication reliance.

9. Are there any emerging alternatives to traditional drugs for dementia agitation?

Yes, recent innovations focus on reducing reliance on traditional antipsychotics and sedatives. One promising approach involves dextromethorphan-quinidine, a combination drug showing efficacy in managing aggression and irritability with fewer extrapyramidal symptoms. Other studies explore the use of cannabinoids or hormone-modulating agents, although these remain experimental. As interest in personalized dementia care grows, researchers are investigating biomarkers that predict which patients will respond best to specific medication for dementia agitation. Future therapies may include more targeted agents that modulate neuroinflammation, a process increasingly linked to behavioral symptoms in dementia.

10. How can families help optimize the management of agitation in dementia without increasing medication?

Families play a crucial role in the successful management of agitation in dementia. By maintaining consistent routines, reducing environmental stressors, and recognizing early signs of distress, caregivers can often prevent escalation. Understanding each patient’s history—such as past traumas, fears, or meaningful activities—can guide interactions that reduce the need for drugs for dementia agitation. When medication becomes necessary, caregivers should remain vigilant for side effects and communicate regularly with medical providers. A shared decision-making model empowers families to balance the use of medicine for dementia agitation with compassionate, person-centered care strategies.

Conclusion: Choosing the Best Medication for Dementia Agitation Requires Compassion, Precision, and Partnership

The treatment of behavioral symptoms in dementia represents one of the most delicate and demanding areas of geriatric care. While the ideal solution would always begin with non-pharmacological interventions, the reality is that medications often play a crucial role in restoring calm and preserving quality of life. Understanding which medicine for dementia agitation is most appropriate—and when to use it—requires both scientific knowledge and clinical wisdom.

From questions about what is the best sedative for dementia patients to decisions about the best med for hallucinations for elderly individuals, each choice must be made with an awareness of the patient’s unique needs, vulnerabilities, and values. Pharmacological options, including SSRIs, antipsychotics, cholinesterase inhibitors, and even mood stabilizers, all have their place—but only within the context of careful assessment and ongoing evaluation.

Ultimately, the goal is not merely to suppress symptoms but to enhance the well-being of those living with dementia. As clinicians and caregivers alike continue to refine the management of agitation in dementia, the most effective treatments will always be those rooted in empathy, guided by evidence, and responsive to the lived experience of each individual. Whether searching for drugs for dementia agitation or wondering “what is the happy pill for dementia patients,” the answer lies not just in a prescription—but in a partnership.

Further Reading:

Agitation and Dementia: Prevention and Treatment Strategies in Acute and Chronic Conditions

An Evidence-Based Approach to the Management of Agitation in the Geriatric Patient