Understanding the Rising Global Burden of Dementia

Dementia is no longer a condition affecting only the elderly in high-income countries; it has become a growing global health crisis. Why is dementia increasing, In recent decades, the prevalence of dementia has risen at an alarming rate, raising pressing questions about why dementia is increasing in both developing and developed regions. The surge in cases is not simply a function of aging populations, though that is certainly a factor. Instead, it is the result of a complex interplay of demographic, environmental, lifestyle, and healthcare-related influences. As we attempt to grasp the scale and underlying causes of this trend, it’s important to examine both the macro-level forces shaping public health and the individual-level risk factors that increase vulnerability to cognitive decline.

This increase in dementia cases is not happening in isolation. It coincides with global shifts in longevity, urbanization, industrialization, and healthcare access. Many countries are experiencing simultaneous demographic transitions that are changing the structure of their populations. As medical technology reduces deaths from infectious disease and cardiovascular events, more individuals are living long enough to develop age-related neurological disorders. Yet the rise in dementia is not a simple outcome of living longer. Researchers and public health experts alike are asking: does everyone get dementia eventually, or are there modifiable risks we can address now to stem the tide?

At the same time, the data reveal dramatic regional variations. The highest rates of dementia in the world are not uniformly distributed; some countries are seeing particularly steep increases. This article explores the reasons why dementia is increasing, considers global disparities in prevalence, and evaluates evidence-based strategies that may help mitigate the growing burden.

You may also like: How to Prevent Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease Naturally: Expert-Backed Strategies to Reduce Your Risk Through Lifestyle and Diet

Aging Populations and the Longevity Paradox

One of the most commonly cited reasons why dementia is increasing worldwide is the rapid aging of populations. This demographic shift is most pronounced in high-income countries, but emerging economies are quickly following suit. As birth rates fall and life expectancy climbs, the proportion of older adults has risen dramatically. Since age is the most significant non-modifiable risk factor for dementia, it follows logically that more elderly people will lead to more dementia cases. However, longevity alone does not paint the full picture.

Interestingly, not everyone who reaches old age develops dementia. This prompts the critical question: does everyone get dementia if they live long enough, or is it possible to age without experiencing substantial cognitive decline? Current research suggests that while dementia risk does increase with age, it is not an inevitable consequence of growing older. Some individuals reach their nineties or even centenarian status with little to no signs of cognitive impairment. Genetic resilience, healthy lifestyles, and socio-environmental protections all play a role in modifying this risk.

As we examine the longevity paradox, we begin to understand that increased life expectancy brings both promise and challenge. While more people are surviving chronic diseases that were once fatal, the aging brain remains vulnerable. Without interventions to preserve cognitive function, the burden of neurodegenerative disease could become unsustainable. Thus, we must look beyond age and explore what else is driving this increase in dementia cases worldwide.

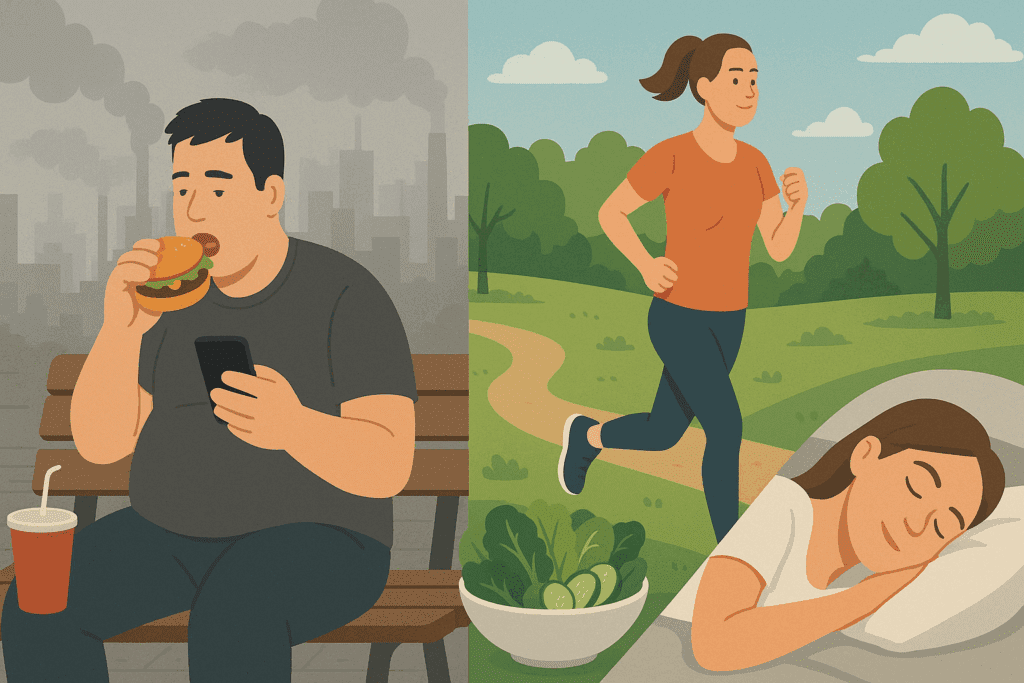

Lifestyle Factors and the Rise of Modifiable Risks

Beyond demographics, lifestyle changes in the modern era have become a major contributor to the global rise in dementia. Urbanization, dietary shifts, decreased physical activity, and increased exposure to pollution have all altered the risk landscape. Diets high in refined carbohydrates, processed foods, and trans fats are now prevalent in many parts of the world. These nutritional patterns contribute to obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease—all of which are known risk factors for cognitive decline.

Physical inactivity also plays a significant role. Sedentary behavior has become more common due to technological advancement and urban lifestyles. Studies have consistently shown that regular exercise supports brain health by enhancing neurogenesis, improving vascular integrity, and reducing inflammation. The widespread abandonment of physically active routines has therefore undermined one of the most powerful non-pharmacologic protections against cognitive deterioration.

Sleep disruption, chronic stress, and substance abuse further complicate the picture. These factors can lead to neuroendocrine imbalances and contribute to the atrophy of brain regions involved in memory and executive function. The interplay of these behavioral risks reveals that the question “does everyone get dementia?” must be considered in context. Clearly, certain patterns of living either elevate or mitigate the likelihood of developing dementia, even in genetically predisposed individuals.

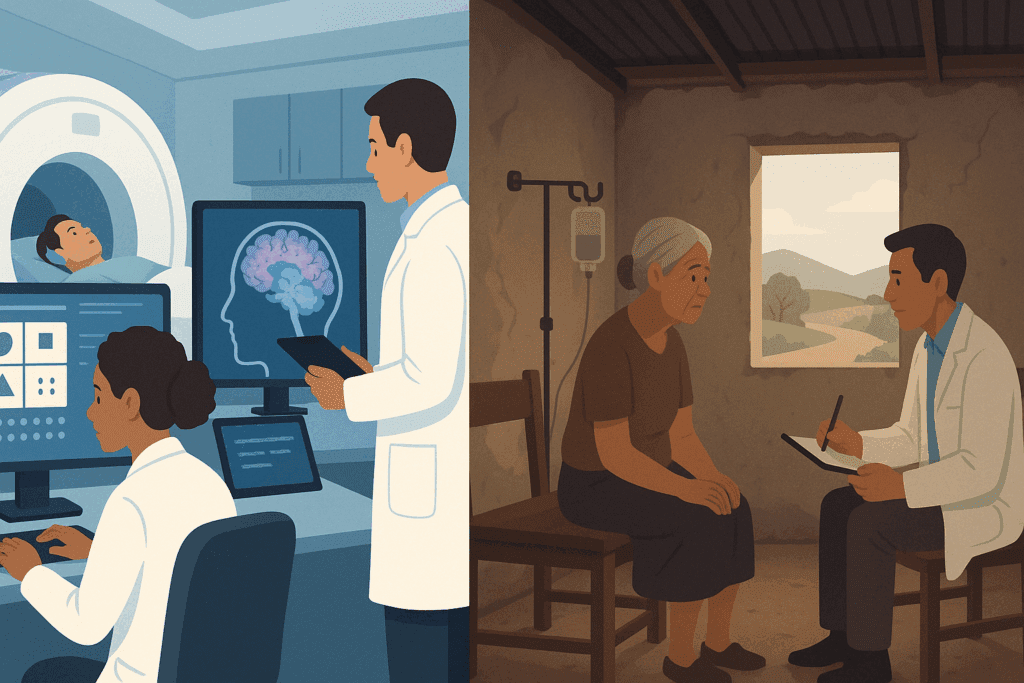

Healthcare Access and Diagnostic Advancements

Another reason why dementia is increasing is the improved ability to diagnose it. With advances in neuroimaging, cognitive testing, and biomarker analysis, clinicians are now better equipped to identify and track neurodegenerative disorders. This has led to a rise in reported cases, not necessarily because the condition is becoming more common, but because it is being recognized more accurately and earlier than before.

In low- and middle-income countries, however, underdiagnosis remains a concern. Many individuals with dementia symptoms never receive a formal diagnosis due to limited healthcare infrastructure, cultural stigma, and lack of training among primary care providers. As awareness improves and diagnostic tools become more accessible, it is likely that prevalence estimates in these regions will increase further. This does not necessarily mean that dementia is spreading faster there, but rather that hidden cases are being brought to light.

While better diagnosis helps us understand the scope of the issue, it also places additional strain on healthcare systems. Early diagnosis is vital for implementing interventions that can delay disease progression. But it also increases the demand for support services, long-term care, and caregiver education. Without adequate planning and resources, healthcare systems may struggle to meet the needs of this growing population.

Environmental and Social Determinants of Brain Health

Environmental exposures are another piece of the puzzle. Air pollution, for example, has emerged as a significant and underappreciated factor in neurodegenerative risk. Studies have found that prolonged exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) is associated with structural brain changes, cognitive impairment, and increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Urban dwellers in polluted cities may therefore face higher dementia risk regardless of their age or genetic predisposition.

Social determinants of health also shape dementia outcomes in profound ways. Loneliness, social isolation, and low educational attainment have all been identified as risk factors. Cognitive reserve—the brain’s ability to cope with damage through alternative neural pathways—is influenced by lifelong learning, occupational complexity, and meaningful social engagement. Societies that promote intellectual stimulation and interpersonal connection may thus see slower cognitive decline at the population level.

The disparities in risk across regions and populations help explain why the highest rates of dementia in the world are often concentrated in areas with high exposure to multiple overlapping risk factors. Addressing these social and environmental contributors is crucial if we are to make meaningful progress in dementia prevention globally.

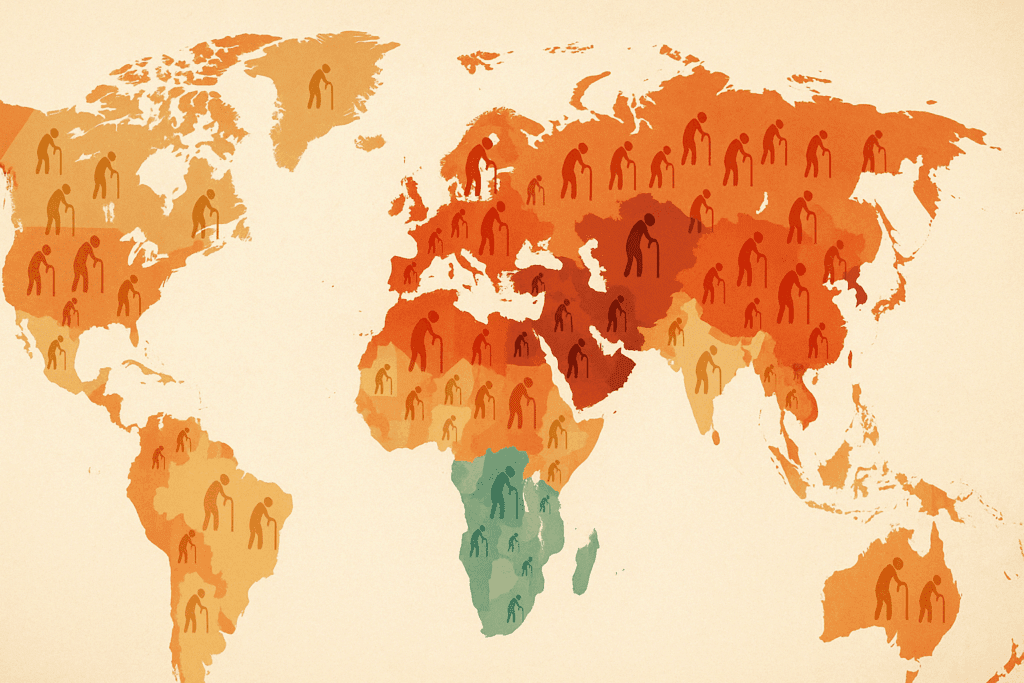

Global Disparities: Where Are the Highest Rates of Dementia in the World?

Dementia does not affect all regions equally. While developed countries currently report the highest absolute numbers due to older populations, some emerging economies are experiencing more rapid increases in prevalence. Latin America, parts of Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa are seeing a steep upward trajectory in dementia cases, often without the accompanying infrastructure to manage the burden.

According to the World Health Organization, regions such as North America and Western Europe have among the highest rates of dementia in the world, with prevalence ranging from 5 to 8 percent of those over the age of 60. However, recent projections suggest that East Asia and South Asia may soon surpass these figures due to demographic expansion and lifestyle shifts. In particular, China and India are expected to face significant challenges due to their enormous aging populations and changing disease profiles.

In contrast, countries with younger demographics have traditionally reported lower dementia rates. However, this trend may shift rapidly as life expectancy increases and urbanization spreads. The key takeaway is that while the highest rates of dementia in the world may currently be found in wealthy nations, the greatest relative growth is expected in regions least prepared to address it.

Regional disparities in healthcare access, education, nutrition, and environmental safety all contribute to the uneven global landscape of dementia. It is therefore essential to approach this issue with a nuanced understanding of local contexts and tailor interventions accordingly.

Can We Prevent Dementia? Evidence-Based Interventions and Hopeful Avenues

Although the question “does everyone get dementia?” continues to circulate in public discourse, the answer from contemporary neuroscience is increasingly hopeful. Numerous studies now support the notion that dementia is not an unavoidable consequence of aging, and that prevention is both possible and practical. The Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care has identified several modifiable risk factors that, if addressed, could prevent up to 40% of dementia cases globally.

Among these interventions, promoting cardiovascular health stands out as particularly effective. Controlling blood pressure, managing diabetes, avoiding smoking, and maintaining a healthy weight can all reduce the risk of cognitive decline. Engaging in regular physical activity not only benefits the heart but also supports synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis.

Cognitive stimulation, whether through formal education, lifelong learning, or mentally challenging activities, builds cognitive reserve and delays symptom onset. Social interaction and emotional well-being are similarly protective. Emerging evidence also highlights the importance of sleep hygiene and stress reduction as key pillars of brain health.

Policy-level interventions are equally vital. Governments must invest in public health campaigns that raise awareness about dementia risk factors and encourage early screening. Equally important is ensuring equitable access to preventive services, particularly in underserved regions where the highest rates of dementia in the world may be emerging without adequate response mechanisms.

A Call for Multidisciplinary Collaboration and Global Solidarity

To effectively address why dementia is increasing, we must adopt a global, multidisciplinary perspective. Collaboration between neurologists, public health officials, policymakers, educators, urban planners, and community leaders is essential. This is not merely a medical issue; it is a societal challenge that touches on aging, equity, infrastructure, and human dignity.

Efforts to mitigate the rise of dementia should include improved training for healthcare providers, increased funding for neuroscience research, and stronger support systems for caregivers. Public health campaigns must target the full spectrum of prevention, from childhood education to elderly care. Cross-sector investment in age-friendly communities, clean air initiatives, and accessible mental health resources can contribute to more resilient societies.

International organizations have a vital role to play. The World Health Organization’s Global Action Plan on the Public Health Response to Dementia provides a strategic framework, but implementation depends on national will and local adaptation. As more countries acknowledge dementia as a public health priority, the opportunity to make meaningful progress becomes more tangible.

Rethinking Our Approach to Cognitive Aging

The notion that cognitive decline is an inevitable part of aging is no longer tenable in light of recent evidence. While age remains the strongest risk factor, dementia is not a universal outcome. The rise in prevalence prompts a deeper consideration of how our environments, choices, and policies shape the aging brain. Recognizing why dementia is increasing leads us to reevaluate our approach to aging, with an emphasis on proactive, lifelong brain health strategies.

This paradigm shift requires a transformation in how we educate the public, design our communities, and allocate our health resources. The earlier we begin to address risk factors—even in childhood and midlife—the more effective our efforts will be. Ultimately, reframing cognitive aging as a dynamic, preventable process empowers individuals and societies alike.

Frequently Asked Questions: Understanding the Global Rise in Dementia

1. What are some lesser-known reasons why dementia is increasing beyond aging and diagnostics?

In addition to aging populations and better diagnostics, a subtler reason why dementia is increasing is the growing impact of endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) found in plastics, pesticides, and industrial pollutants. These substances can interfere with brain hormone signaling and are increasingly being studied for their long-term neurodegenerative effects. Another emerging factor is microvascular dysfunction—damage to small blood vessels in the brain due to conditions like hypertension or chronic kidney disease—which is increasingly recognized as a precursor to dementia. Additionally, prolonged sleep deprivation, often normalized in competitive work cultures, is contributing to rising dementia risk, particularly among younger professionals. As we refine our understanding of why dementia is increasing, it is becoming clear that environmental and occupational exposures deserve more focused attention.

2. Does everyone get dementia eventually, or are there clear predictors of resilience?

Although the question “does everyone get dementia?” reflects a widespread concern, research shows that some people possess protective traits that dramatically lower their lifetime risk. Higher levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein that supports neuroplasticity, are associated with better cognitive resilience. Individuals with certain genetic profiles, such as those carrying the protective APOE2 variant, also show reduced vulnerability. Regular engagement in bilingualism or musical training appears to bolster cognitive reserve, creating alternative neural pathways that help the brain adapt to damage. So no, not everyone gets dementia; genetics, lifestyle, and intellectual engagement can collectively preserve brain function well into old age.

3. Which parts of the world are expected to see the steepest increase in dementia rates in the coming decades?

While the highest rates of dementia in the world are currently concentrated in developed nations, future projections suggest that low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) will experience the fastest growth. Nations in Southeast Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and parts of South America are aging rapidly without sufficient healthcare infrastructure to support geriatric and neurological care. The rise in urbanization, dietary changes, and declining physical activity in these regions further explains why dementia is increasing there so quickly. Unlike high-income countries, where dementia growth is plateauing, these regions face a dual challenge: increasing prevalence and inadequate preparation. Consequently, global health initiatives must focus on capacity building in these areas to slow the trajectory.

4. How does climate change influence dementia trends globally?

Emerging evidence indicates that climate change may be an indirect yet potent factor in why dementia is increasing. Heatwaves, for instance, exacerbate cardiovascular strain and dehydration in the elderly, both of which impair cognitive function. Furthermore, climate-driven wildfires release neurotoxic particulates into the air, increasing the risk of vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s-like symptoms. Food insecurity and displacement caused by environmental degradation also create chronic stress, which contributes to long-term cognitive decline. These cascading effects show that addressing climate resilience could play an unexpected but vital role in mitigating future dementia risk across vulnerable populations.

5. Are there any misconceptions about who is most at risk for dementia?

A common misconception is that dementia only affects people over the age of 70, yet early-onset dementia can begin in individuals as young as 40. Another flawed assumption is that dementia primarily impacts those with no formal education; while lower education levels are a risk factor, highly educated individuals are not immune. Additionally, people often believe dementia is solely a memory disorder, when in fact it frequently begins with changes in decision-making, personality, or spatial awareness. As we investigate why dementia is increasing, it’s important to debunk stereotypes and recognize that risk is widespread and often overlooked in younger or high-functioning populations. Tailoring education and screening tools to diverse demographics will be key in early intervention.

6. How might artificial intelligence and digital technologies reshape dementia care and prevention?

Artificial intelligence (AI) is poised to become a transformative force in both the diagnosis and management of dementia. AI-powered imaging analysis can detect microstructural brain changes before clinical symptoms arise, offering a new frontier in predictive diagnostics. Mobile applications using natural language processing may soon identify subtle changes in speech patterns indicative of early cognitive decline. On the prevention side, personalized digital coaching systems can guide users toward healthier lifestyles based on genetic and behavioral data. These innovations are particularly crucial in regions with the highest rates of dementia in the world, where healthcare access is limited and mobile technology is more widely available. As these tools evolve, they could democratize dementia care and significantly curb why dementia is increasing at such a rapid pace.

7. Is there a connection between chronic loneliness and the global rise in dementia?

Yes, and it is more profound than many realize. Chronic loneliness activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, leading to prolonged stress hormone release, which can damage hippocampal neurons critical for memory. This social stress has been shown to double the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in some studies. In societies where digital communication has replaced face-to-face interaction, chronic isolation may be subtly fueling why dementia is increasing. Countries experiencing demographic aging and weakening intergenerational bonds are particularly vulnerable. Building community-centered public health models that prioritize social engagement could become a key intervention in addressing this silent driver.

8. How does occupational exposure contribute to dementia risk in high-risk regions?

In certain industrial and agricultural sectors, long-term exposure to neurotoxic chemicals such as organophosphates, solvents, and heavy metals has been linked to elevated dementia risk. These exposures are particularly common in regions with minimal occupational safety regulations, many of which also report the highest rates of dementia in the world. For instance, farmworkers and factory employees in rapidly industrializing countries may inhale or absorb toxins without proper protective equipment. Over time, this cumulative exposure damages the central nervous system and accelerates neurodegeneration. Improved enforcement of workplace safety and environmental controls could therefore be a strategic target for dementia prevention efforts globally.

9. Are multigenerational households protective or risky when it comes to dementia trends?

Multigenerational households can offer both protective and challenging dynamics. On one hand, older adults living with family are more likely to stay socially engaged, receive consistent care, and maintain routines that support cognitive health. On the other hand, if such households experience high stress, poor communication, or caregiver burnout, they may exacerbate emotional distress in the elderly, indirectly increasing dementia risk. Cultural expectations in regions with the highest rates of dementia in the world often mandate family caregiving, but without institutional support, the burden can backfire. Community education programs and caregiver support networks are essential to maximize the benefits of this living arrangement. Ultimately, the context of care matters just as much as the structure.

10. What role does health literacy play in the global dementia landscape?

Health literacy—the ability to obtain, understand, and use health information—plays a pivotal role in whether individuals recognize early dementia symptoms and seek timely care. In areas where health literacy is low, people may misattribute signs of dementia to normal aging or spiritual phenomena, delaying diagnosis and care. This delay partly explains why dementia is increasing unnoticed in some communities until it becomes a major crisis. Conversely, populations with high health literacy are more likely to engage in prevention strategies and adhere to treatment plans. Raising health literacy across generations could act as a preventive force, especially in countries projected to experience the highest rates of dementia in the world over the next two decades.

Conclusion: Understanding Why Dementia Is Increasing and What We Can Do About It

The global rise in dementia is a complex, multifaceted phenomenon that defies simple explanation. While aging populations are a contributing factor, they do not tell the full story. Lifestyle changes, environmental exposures, diagnostic improvements, and healthcare disparities all intersect to influence dementia trends. The reality that not everyone will develop dementia—even into advanced age—should offer both hope and motivation. Understanding why dementia is increasing requires us to look beyond biology alone and consider the broader social, behavioral, and policy environments in which people age.

Furthermore, acknowledging where the highest rates of dementia in the world are found helps us target our interventions more effectively. Rather than a one-size-fits-all approach, we must tailor strategies to the cultural, economic, and healthcare contexts of specific populations. The evidence is clear: dementia is not inevitable, and prevention is possible. As we continue to ask whether everyone gets dementia, we are increasingly met with answers grounded in science, strategy, and solidarity.

By embracing a comprehensive, collaborative approach rooted in EEAT principles—experience, expertise, authoritativeness, and trustworthiness—we can chart a path forward. One where rising dementia rates do not represent defeat, but rather a call to action that inspires innovation, compassion, and resilience in the face of one of our most pressing public health challenges.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out.

Further Reading:

Current status of research on the modifiable risk factors of dementia in India: A scoping review

Disclaimer

The information contained in this article is provided for general informational purposes only and is not intended to serve as medical, legal, or professional advice. While Health11News strives to present accurate, up-to-date, and reliable content, no warranty or guarantee, expressed or implied, is made regarding the completeness, accuracy, or adequacy of the information provided. Readers are strongly advised to seek the guidance of a qualified healthcare provider or other relevant professionals before acting on any information contained in this article. Health11News, its authors, editors, and contributors expressly disclaim any liability for any damages, losses, or consequences arising directly or indirectly from the use, interpretation, or reliance on any information presented herein. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of Health11News.