The modern diet, abundant in refined carbohydrates and sweetened beverages, has invited a cascade of public health concerns over the last several decades. While much of the focus has been directed toward diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and obesity, a growing body of scientific literature is illuminating another alarming consequence of excessive sugar consumption: its potential influence on brain aging and dementia. As researchers delve into the biological underpinnings of cognitive decline, questions like “does sugar cause dementia” and what role glucose plays in brain function are drawing serious attention from neuroscientists, geriatricians, and nutritional epidemiologists alike.

You may also like: How to Prevent Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease Naturally: Expert-Backed Strategies to Reduce Your Risk Through Lifestyle and Diet

Sugar and the Brain: A Delicate Balance

Glucose is the primary energy source for the brain, powering the billions of neurons and glial cells responsible for everything from memory consolidation to emotional regulation. Under normal circumstances, this energy supply supports cognitive resilience and plasticity. However, when glucose levels in the bloodstream surge due to the overconsumption of refined sugars, particularly white sugar, the effects may be far from benign. Emerging evidence suggests that dysregulated glucose metabolism may impair neuronal health, leading to inflammatory responses and oxidative stress that accelerate neurodegeneration.

In scholarly explorations of the relationship between white sugar and effects on dementia, researchers have increasingly linked high-glycemic diets with impaired hippocampal function, a region of the brain central to memory and learning. These findings underscore the importance of metabolic equilibrium and raise concerns about the long-term cognitive consequences of chronic sugar overload. Rather than acting as mere fuel, sugar in excess may become a metabolic liability, undermining the brain’s structural and functional integrity over time.

Does Sugar Cause Dementia? Understanding the Complexity of the Question

The question of whether sugar causes dementia does not lend itself to a simple yes or no answer. Scientific discourse on this topic stresses the importance of distinguishing between causation and correlation. While numerous longitudinal studies have observed associations between high sugar intake and increased dementia risk, causality has yet to be definitively established. Nonetheless, plausible biological mechanisms are mounting, reinforcing the idea that sugar-laden diets may create conditions conducive to cognitive decline.

Hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, and chronic inflammation—three well-documented consequences of excessive sugar consumption—are increasingly recognized as shared pathological features between metabolic syndrome and various forms of dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease. Inflammation disrupts synaptic communication, while insulin resistance impairs the brain’s ability to process glucose efficiently, leading to cellular energy deficits and even neuronal death. These phenomena suggest that while sugar may not directly cause dementia, it may serve as a key modifiable risk factor in its development.

The Impact of White Sugar and Effects on Dementia in Scholarly Articles

A review of scholarly literature reveals a growing consensus around the deleterious effects of white sugar on cognitive health. In particular, articles published in peer-reviewed journals such as the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, Neurobiology of Aging, and Frontiers in Nutrition have explored how high-sucrose diets influence markers of brain aging. Findings from animal models show that mice fed with high sugar diets exhibit increased beta-amyloid plaques and tau tangles—hallmarks of Alzheimer’s pathology—compared to controls. Meanwhile, human epidemiological studies have reported that individuals with consistently elevated blood sugar levels face significantly higher rates of cognitive impairment in later life.

These insights support the argument that white sugar and effects on dementia should be more prominently addressed in public health policy and dietary guidelines. Despite the fact that many scholarly articles caution against overgeneralization, the evidence consistently points toward a troubling relationship between refined sugar consumption and deteriorating brain health, particularly in vulnerable populations such as the elderly and those with metabolic disorders.

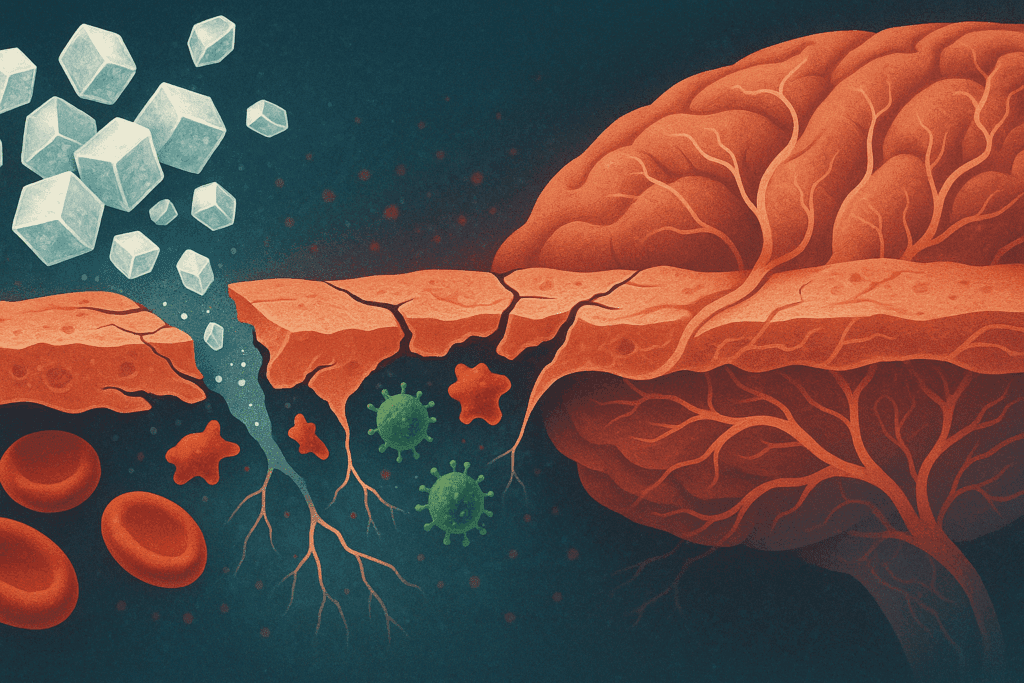

Sugar and the Blood-Brain Barrier: A Compromised Shield

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) plays a critical role in protecting the brain from harmful substances circulating in the bloodstream. However, chronic hyperglycemia has been shown to impair the integrity of this barrier, allowing inflammatory agents and toxins to penetrate neural tissues more easily. This weakening of the BBB is yet another pathway through which sugar may contribute to the neuroinflammatory cascade seen in various forms of dementia.

When researchers investigate sugar and dementia, they often point to the cascade of events that begins with high blood sugar and ends with neuronal damage. One of the lesser-known but crucial insights emerging from scholarly literature is that excessive sugar does not merely lead to vascular issues—it may directly alter the permeability of cerebral vasculature. This makes the brain more susceptible to the kinds of microvascular damage that are increasingly implicated in cognitive decline.

Insulin Resistance in the Brain: The Link Between Diabetes and Dementia

One of the most compelling bodies of evidence connecting sugar to dementia risk involves insulin resistance within the brain. Sometimes referred to as “type 3 diabetes,” insulin resistance in the brain hinders the uptake and utilization of glucose by neurons, effectively starving them of energy. This condition shares many molecular characteristics with Alzheimer’s disease and may help explain why individuals with type 2 diabetes have a 50 to 100 percent higher risk of developing dementia.

The role of insulin is not limited to regulating glucose levels. In the brain, it also supports synaptic plasticity and the modulation of neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine, which is essential for memory and learning. When insulin signaling falters, these processes break down, contributing to the cognitive deficits observed in both diabetic and prediabetic populations. Thus, when addressing questions like “does sugar cause dementia,” it becomes evident that the metabolic dysfunction instigated by high sugar diets plays a major role in shaping long-term cognitive trajectories.

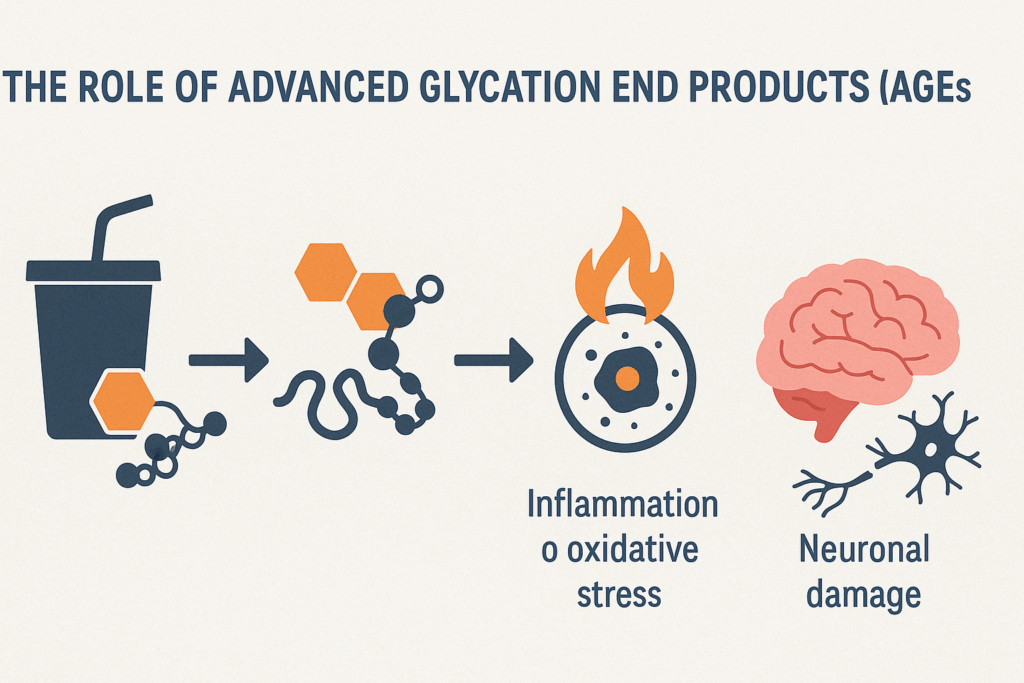

The Role of Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs)

Another critical mechanism linking sugar intake to neurodegeneration involves the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs). These harmful compounds form when sugars react with proteins or fats in the body, creating molecules that accumulate over time and promote inflammation and oxidative stress. AGEs have been detected in high concentrations in the brains of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and are believed to contribute to the misfolding of proteins like beta-amyloid and tau.

Notably, the generation of AGEs is significantly accelerated by diets high in refined sugars, especially white sugar. This further validates concerns raised in white sugar and effects on dementia scholarly articles, where researchers consistently emphasize the pro-inflammatory and cytotoxic nature of AGEs. By fostering oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction, AGEs damage cellular components essential for brain function and viability.

Nutritional Strategies to Reduce Sugar-Related Dementia Risk

While the scientific literature continues to investigate how sugar and dementia are interconnected, actionable dietary strategies are emerging as powerful tools for risk reduction. Replacing high-glycemic foods with complex carbohydrates such as whole grains, legumes, and vegetables helps regulate blood sugar levels and reduce glycemic load. Additionally, diets rich in antioxidants and anti-inflammatory nutrients—such as the Mediterranean and MIND diets—have been associated with lower dementia incidence.

These dietary patterns emphasize whole, minimally processed foods and discourage added sugars, particularly those found in sweetened beverages and desserts. Practical steps, such as preparing meals at home, reading nutrition labels, and limiting intake of processed snacks, can significantly reduce one’s exposure to hidden sugars. As questions like “does sugar cause dementia” continue to garner public interest, empowering individuals with evidence-based strategies for prevention becomes a crucial aspect of public health messaging.

Aging, Sugar Sensitivity, and Cognitive Vulnerability

The aging brain becomes increasingly vulnerable to metabolic disturbances, making older adults particularly susceptible to the effects of high sugar consumption. With advancing age, there is a natural decline in insulin sensitivity, mitochondrial efficiency, and antioxidant defenses. When coupled with a diet rich in refined sugars, these age-related changes may accelerate the onset of cognitive decline and increase susceptibility to neurodegenerative diseases.

Research also suggests that aging alters the way the brain metabolizes glucose, with regional reductions in glucose uptake observed in individuals at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. This metabolic deficiency may be exacerbated by chronic sugar intake, leading to energy shortages in key brain regions responsible for memory and executive function. Consequently, understanding how sugar affects the aging brain is paramount in designing interventions aimed at preserving cognitive health in older populations.

Public Health Implications and the Need for Education

Given the mounting evidence linking sugar and dementia, there is a growing imperative to integrate this knowledge into public health campaigns and medical education. While sugar has long been targeted for its role in weight gain and metabolic syndrome, its implications for brain health remain underemphasized in most dietary guidelines. Educating the public about the neurological consequences of excessive sugar consumption may help shift behaviors and reduce the societal burden of dementia.

One promising approach involves integrating nutritional counseling into routine clinical care, particularly for populations at risk of both metabolic and cognitive disorders. In doing so, healthcare providers can reinforce the importance of diet as a modifiable risk factor, helping patients adopt sustainable changes that protect brain function. As more scholarly articles continue to examine the white sugar and effects on dementia, these insights must translate into actionable policies and educational outreach.

Rethinking Sugar in the Context of Cognitive Longevity

Reevaluating the role of sugar in our diets requires a broader understanding of how nutrition shapes brain health over the lifespan. While it may not be accurate to assert definitively that sugar causes dementia, the constellation of evidence from molecular biology, epidemiology, and neuroscience strongly indicates that excessive sugar consumption can compromise cognitive resilience. These findings challenge us to consider not only what we eat, but how our food choices influence the trajectory of our mental faculties as we age.

Rather than waiting for late-stage symptoms to emerge, proactive dietary interventions that limit sugar intake can serve as preventive strategies to protect against future decline. The science behind sugar and dementia continues to evolve, but its central message remains consistent: dietary patterns matter, and small, consistent changes can yield significant dividends for cognitive longevity.

Frequently Asked Questions: Sugar and Dementia

1. How might sugar influence brain inflammation differently in people with preexisting cognitive conditions?

In individuals with early-stage cognitive impairment or mild cognitive decline, sugar intake may exacerbate neuroinflammatory processes more aggressively than in those with healthy brains. This is likely due to a pre-sensitized neuroimmune system that responds to metabolic stressors, including sugar, with heightened inflammatory signaling. For those already experiencing compromised blood-brain barrier integrity, even modest elevations in glucose can intensify neuronal damage. Some recent research points to a unique vulnerability among people with subjective cognitive decline, where even short-term high sugar intake can accelerate biomarkers linked to dementia. These insights expand our understanding of the nuanced relationship between sugar and dementia, particularly in predisposed populations.

2. Are the effects of natural sugars like honey or fruit sugars different from white sugar when it comes to dementia risk?

While natural sugars such as fructose in fruit and glucose in honey do elevate blood sugar levels, they often come packaged with fiber, antioxidants, and micronutrients that mitigate their impact on metabolic health. In contrast, white sugar delivers a concentrated glycemic load without nutritional offsets, intensifying insulin resistance and oxidative stress. This distinction is critical in scholarly discussions on white sugar and effects on dementia, as the context in which sugar is consumed alters its physiological outcome. Diets rich in whole fruits are typically associated with a reduced risk of dementia, whereas those high in refined sugar demonstrate the opposite trend. Thus, the source and nutritional context of sugar matter greatly in determining its cognitive effects.

3. Could periodic sugar intake be protective or beneficial for brain function in any way?

Surprisingly, some evidence suggests that controlled, moderate glucose intake may temporarily enhance working memory and attention, especially in older adults. This is known as the “glucose facilitation effect,” and it’s most effective when the brain is under cognitive load or during short-term mental tasks. However, the line between helpful and harmful is thin—frequent consumption can quickly shift the balance toward inflammation and metabolic disruption. The key lies in understanding the threshold at which sugar’s benefits give way to long-term risks associated with sugar and dementia. Timing, dosage, and individual metabolic health all influence whether a brief glucose spike will be cognitively helpful or harmful.

4. How do psychological stress and sugar interact in the context of dementia risk?

Psychological stress raises cortisol levels, which in turn can increase cravings for high-sugar foods and disrupt insulin sensitivity. This stress-sugar cycle contributes to metabolic imbalance and primes the brain for inflammatory responses. Chronic stress also affects hippocampal function, and when compounded by poor glycemic control, the risk for cognitive decline becomes more pronounced. Research exploring sugar and dementia often highlights this interaction, suggesting that individuals under frequent emotional distress may be more vulnerable to the damaging effects of sugar on the brain. This dual impact underscores the importance of holistic interventions that target both diet and mental well-being.

5. What role do gut microbiota play in moderating the brain’s response to sugar?

Gut health has emerged as a crucial intermediary between sugar intake and brain function. Diets high in white sugar can disrupt microbial diversity, leading to dysbiosis—a condition that promotes systemic inflammation and alters neurotransmitter production. Some white sugar and effects on dementia scholarly articles now emphasize the gut-brain axis as a potential target for intervention. Certain bacteria thrive on high-sugar diets and may produce neurotoxic metabolites that cross the blood-brain barrier. Enhancing gut health with probiotics and prebiotics may buffer some of the cognitive risks associated with sugar-heavy diets, though more human studies are needed.

6. Are artificial sweeteners a safer option for people concerned about sugar and dementia?

The safety of artificial sweeteners in the context of dementia prevention is still debated. Some evidence suggests that certain non-nutritive sweeteners may disrupt insulin signaling or alter gut microbiota in ways that mirror the effects of sugar. While they don’t raise blood glucose directly, their influence on brain health remains unclear. Research exploring the broader landscape of sugar and dementia has started to include artificial sweeteners in its scope, particularly focusing on long-term neuroendocrine responses. As such, while artificial sweeteners may be a short-term tool for reducing sugar, their cognitive safety profile warrants caution.

7. Can early dietary changes offset years of high sugar consumption in relation to dementia risk?

The human brain possesses remarkable plasticity, and evidence suggests that even late-stage dietary changes can yield cognitive benefits. Reducing sugar intake can restore some insulin sensitivity, decrease inflammation, and slow neurodegenerative processes. Studies focusing on white sugar and effects on dementia indicate that metabolic improvements can occur within weeks of dietary intervention. However, earlier changes typically yield greater long-term protection. Those who act preventively rather than reactively are more likely to preserve cognitive function and reduce dementia-related pathology.

8. Is there a genetic component that influences how sugar affects dementia development?

Yes, genetic factors such as the APOE4 allele have been shown to amplify the brain’s vulnerability to metabolic disturbances, including those caused by high sugar intake. Carriers of this gene often display impaired glucose metabolism in the brain even before clinical symptoms arise. For these individuals, the connection between sugar and dementia may be more direct and pronounced. White sugar and effects on dementia scholarly articles have increasingly called for gene-specific dietary guidelines as a way to personalize dementia prevention. Genetic testing may help inform more effective dietary interventions tailored to individual risk profiles.

9. What impact does sugar have on cognitive recovery after brain injury or stroke?

Post-injury neuroplasticity is heavily dependent on metabolic stability and nutrient-rich diets. Excess sugar intake after events like stroke or traumatic brain injury may hinder recovery by promoting inflammation and delaying neural repair. Some research now investigates how sugar and dementia-related pathways also apply to post-injury recovery models. For instance, insulin resistance post-stroke may impair neurogenesis in the hippocampus, limiting rehabilitation outcomes. A low-glycemic, anti-inflammatory diet is increasingly recommended for optimizing brain recovery and minimizing secondary cognitive decline.

10. What future research directions are most promising in understanding sugar and dementia?

Emerging areas of interest include epigenetic modifications triggered by long-term sugar intake, the role of circadian rhythms in glucose metabolism, and individualized microbiome profiles that affect cognitive vulnerability. Scholars are also focusing on how white sugar and effects on dementia evolve across different life stages and ethnic populations. Technological advances in brain imaging and wearable glucose monitoring are enhancing our ability to map real-time metabolic effects on cognition. Additionally, longitudinal studies integrating dietary patterns with genetic and lifestyle variables are refining our understanding of the question, “does sugar cause dementia?” These multidimensional approaches promise to unravel the complexity of sugar’s role in brain aging with unprecedented clarity.

Final Reflections: What the Science of Sugar and Dementia Teaches Us About Protecting the Brain

As we synthesize decades of research into a clearer picture of how sugar interacts with brain function, the public health message grows more urgent and more actionable. Scientific studies, including a multitude of white sugar and effects on dementia scholarly articles, paint a compelling picture of sugar’s impact on inflammation, insulin signaling, and neural health. These findings add dimension to the ongoing conversation about what constitutes a brain-healthy lifestyle and highlight the pivotal role of diet in shaping cognitive outcomes.

While the question “does sugar cause dementia” may remain technically open-ended from a clinical perspective, there is little doubt that sugar contributes significantly to the conditions that foster cognitive decline. The goal, then, is not to eliminate sugar entirely—an unrealistic and perhaps unnecessary pursuit—but to develop a more conscious, informed approach to its consumption. By recognizing the potential consequences of excessive sugar intake and adopting dietary strategies that prioritize whole, nutrient-dense foods, individuals can take meaningful steps toward safeguarding their brain health.

In conclusion, the interplay between sugar and dementia underscores the importance of preventative healthcare grounded in evidence-based nutrition. It challenges conventional thinking around dietary habits and invites both individuals and healthcare systems to prioritize brain health through everyday food choices. As the science continues to unfold, the message is clear: our relationship with sugar is not just a matter of taste or metabolism—it may very well be a cornerstone of cognitive longevity.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out.

Further Reading:

Dietary Sugar Intake Associated with a Higher Risk of Dementia in Community-Dwelling Older Adults

Disclaimer

The information contained in this article is provided for general informational purposes only and is not intended to serve as medical, legal, or professional advice. While Health11News strives to present accurate, up-to-date, and reliable content, no warranty or guarantee, expressed or implied, is made regarding the completeness, accuracy, or adequacy of the information provided. Readers are strongly advised to seek the guidance of a qualified healthcare provider or other relevant professionals before acting on any information contained in this article. Health11News, its authors, editors, and contributors expressly disclaim any liability for any damages, losses, or consequences arising directly or indirectly from the use, interpretation, or reliance on any information presented herein. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of Health11News.