In an era where nutrition is increasingly recognized as foundational to cognitive health, questions about the role of vitamins in brain function—and dysfunction—are more relevant than ever. Among the many concerns surfacing in public discourse is a seemingly paradoxical one: can vitamins cause dementia? While vitamins are typically championed for their protective effects, some experts are now exploring whether certain types, doses, or combinations may contribute to cognitive decline in unexpected ways. This inquiry becomes especially complex when we examine the growing body of evidence around vitamin D and its intricate relationship with dementia risk. As researchers delve deeper into how micronutrients affect neurobiology, a clearer—but more nuanced—picture is beginning to emerge.

You may also like: How to Prevent Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease Naturally: Expert-Backed Strategies to Reduce Your Risk Through Lifestyle and Diet

Understanding the Brain’s Nutritional Demands

The brain is an energy-intensive organ, accounting for roughly 20 percent of the body’s total energy expenditure despite comprising only about two percent of its mass. Its functional integrity depends on a constant and optimal supply of nutrients, including essential vitamins and minerals that regulate everything from neurotransmitter synthesis to mitochondrial efficiency. Deficiencies in B vitamins, omega-3 fatty acids, and antioxidants like vitamin E have long been associated with impaired cognitive performance. However, emerging evidence suggests that both deficiency and excess can be detrimental, prompting renewed scrutiny of the delicate balance that must be maintained for long-term brain health.

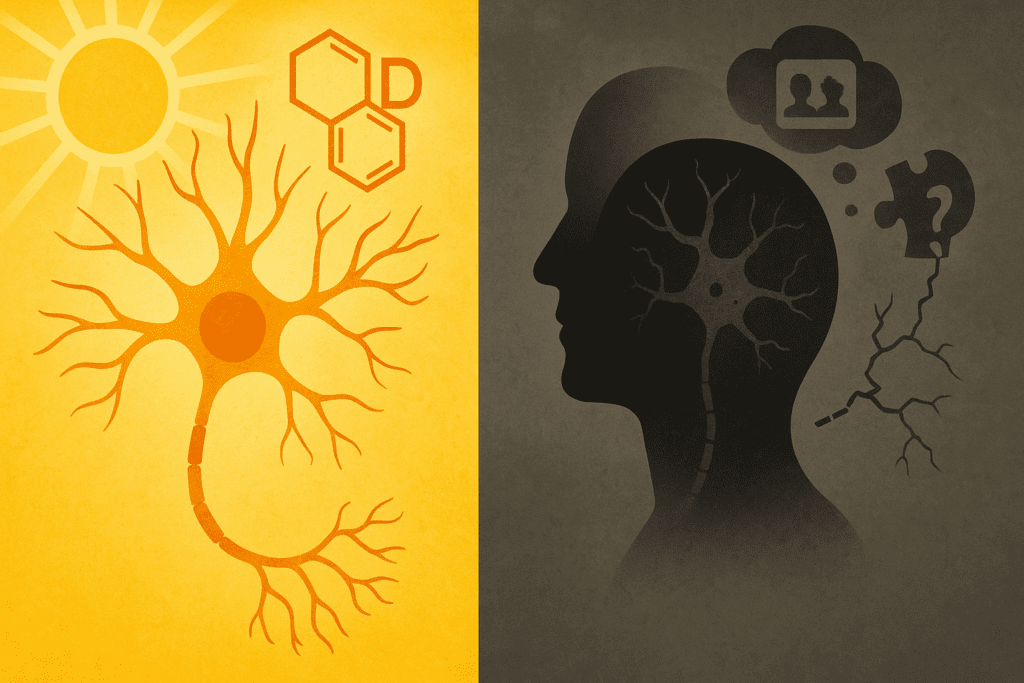

The body’s ability to process and utilize vitamins changes with age, making older adults particularly vulnerable to both deficiency and toxicity. For example, age-related changes in gastrointestinal absorption, liver metabolism, and kidney function can alter how vitamins are stored and excreted. This shift is especially relevant in the context of vitamin D, a fat-soluble vitamin that plays multiple roles in immune regulation, calcium homeostasis, and neuronal health. With age, the skin’s capacity to synthesize vitamin D from sunlight declines, and dietary intake often becomes insufficient, raising concerns about deficiency—and leading to widespread supplementation.

Vitamin D and Cognitive Function: A Complex Relationship

Vitamin D is increasingly recognized for its neuroprotective properties. It modulates calcium signaling in neurons, supports the synthesis of neurotrophic factors, and exerts anti-inflammatory effects that may protect the brain from neurodegenerative processes. Observational studies have consistently shown that low serum levels of vitamin D are associated with an increased risk of cognitive decline and dementia. These findings have spurred interest in the potential role of vitamin D supplementation as a preventive strategy.

Yet despite these promising associations, the question remains: does vitamin D dementia protection hold up under closer scrutiny? Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), which are considered the gold standard for establishing causality, have yielded mixed results. Some trials report modest cognitive benefits from vitamin D supplementation in deficient populations, while others find no significant effects. The heterogeneity of study designs, doses, and participant characteristics complicates interpretation, suggesting that the relationship between vitamin D and cognitive health is far from straightforward.

Adding another layer of complexity is the possibility that excessive vitamin D intake—particularly from high-dose supplements—could paradoxically impair neurological function. While rare, cases of vitamin D toxicity have been documented, and symptoms may include confusion, disorientation, and cognitive changes that mimic early dementia. This raises the important question: can vitamins cause dementia when taken inappropriately or excessively? In the case of vitamin D, emerging research suggests that the answer may be yes, at least under specific conditions.

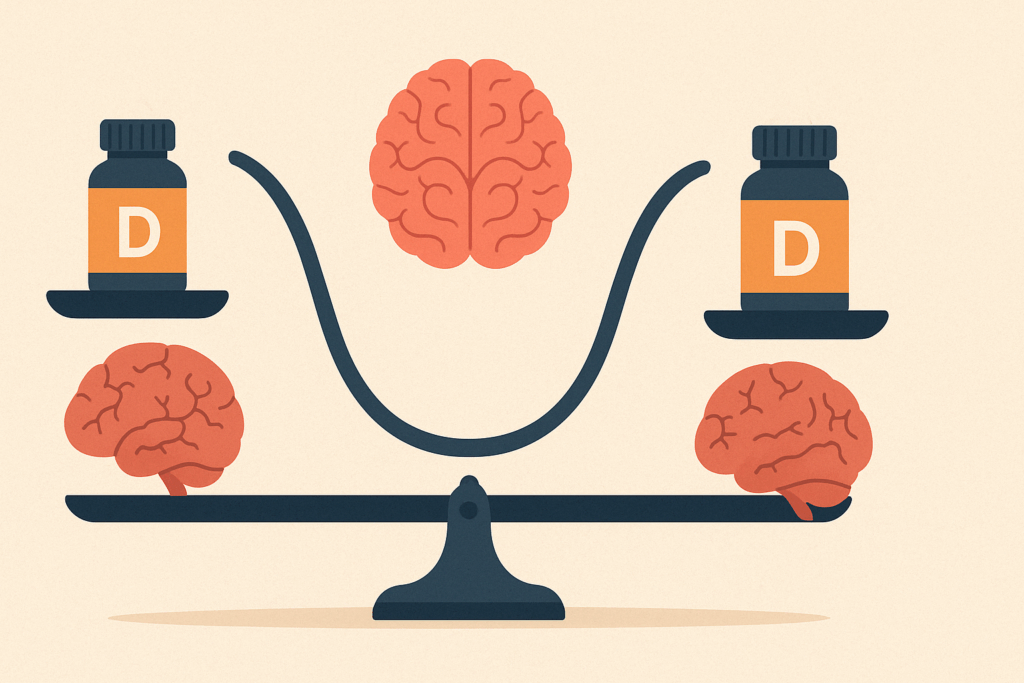

Investigating the Threshold Between Deficiency and Toxicity

Understanding how vitamin D affects brain health requires attention to dose-dependent effects. A growing body of literature points to a U-shaped curve, where both low and high levels are associated with adverse outcomes. For instance, a study published in JAMA Neurology found that both deficient and excessive serum concentrations of vitamin D were linked to increased risk of all-cause dementia in older adults. These findings suggest that maintaining vitamin D within an optimal physiological range is critical—and that more is not always better.

Compounding the issue is the increasing prevalence of over-the-counter vitamin D supplements, many of which provide doses far exceeding the recommended daily allowance. Individuals often self-prescribe these supplements in the belief that they are universally beneficial, sometimes in response to non-specific symptoms like fatigue or brain fog. However, without proper monitoring of blood levels, such practices may inadvertently lead to hypervitaminosis D, characterized by elevated calcium levels, vascular calcification, and even cognitive disturbances. It is in this context that the concern over whether vitamins can cause dementia gains credibility and clinical urgency.

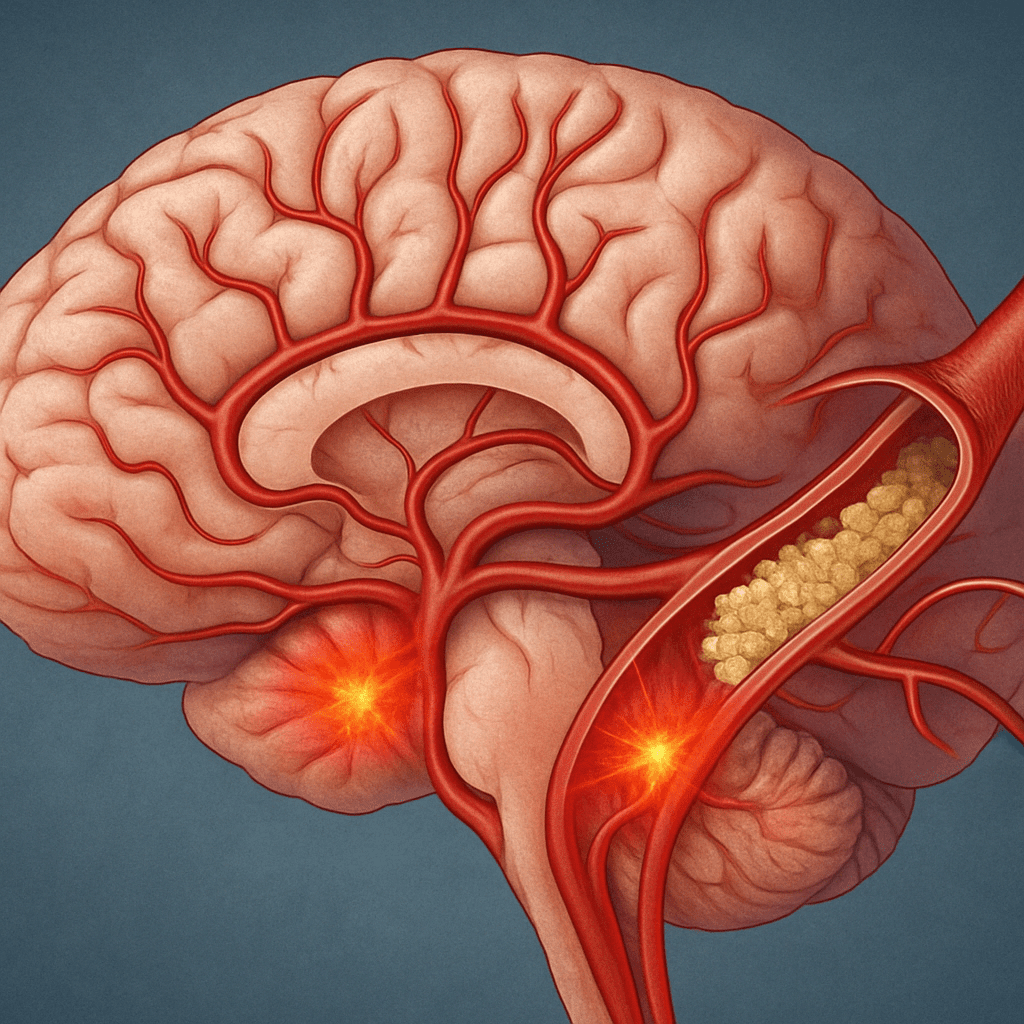

Mechanisms Linking Excessive Vitamin D to Brain Health Risks

The potential for vitamin D to cause cognitive impairment when consumed in excess is supported by several biological mechanisms. One such mechanism involves calcium dysregulation. Vitamin D increases intestinal calcium absorption, and in toxic doses, this can lead to hypercalcemia—a condition that may cause confusion, lethargy, and impaired concentration. Chronic hypercalcemia can also contribute to vascular calcification, including in cerebral vessels, potentially impairing blood flow to critical brain regions.

Another potential pathway involves oxidative stress. While vitamin D has antioxidant properties at physiological levels, excessive intake may disrupt redox balance and promote inflammation, especially in individuals with underlying metabolic or vascular conditions. These effects could contribute to neurodegenerative processes, particularly in the context of Alzheimer’s disease, where inflammation and oxidative stress are central features. Thus, while vitamin D dementia prevention remains a hopeful prospect, the possibility of harm underlines the need for cautious, individualized supplementation.

Clinical Evidence: Can Vitamins Cause Dementia?

Although the majority of research has focused on vitamin deficiencies and their contribution to cognitive decline, a smaller but growing body of literature is beginning to explore whether vitamin excess—particularly from supplements—can lead to dementia-like symptoms. Case studies have documented instances in which excessive intake of vitamins A, D, and B6 has resulted in neurological symptoms, some of which were reversible upon discontinuation. While these cases are relatively rare, they serve as a critical reminder that vitamins are bioactive compounds with the potential to disrupt physiological systems when misused.

Moreover, a 2021 review in the journal Nutrients examined the neurocognitive effects of excessive vitamin intake and concluded that while causal relationships are not yet firmly established, there is sufficient evidence to warrant caution, particularly in the use of high-dose supplements in elderly populations. In this demographic, polypharmacy, age-related metabolic changes, and the presence of chronic disease may amplify the risks associated with over-supplementation. In short, the answer to the question “can vitamins cause dementia” may depend on context, dosage, and individual susceptibility.

The Role of Personalized Nutrition and Monitoring

Given the complexity of nutrient-brain interactions, a one-size-fits-all approach to vitamin supplementation is no longer tenable. Personalized nutrition—grounded in genetic, metabolic, and lifestyle factors—offers a more precise framework for optimizing cognitive health. This includes routine monitoring of serum vitamin levels, particularly in individuals at risk for cognitive decline, and tailoring supplement use to meet specific needs without exceeding safe thresholds.

Healthcare providers are increasingly called upon to guide patients through the often-confusing landscape of nutritional supplements. This includes evaluating the necessity, dosage, and potential interactions of each supplement within the broader context of a patient’s health status. For vitamin D, regular testing of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels can help ensure that supplementation achieves therapeutic goals without crossing into potentially harmful territory. Such monitoring is especially critical for older adults, individuals with limited sun exposure, and those with conditions that affect fat absorption, such as celiac disease or chronic pancreatitis.

Public Health Implications and the Need for Awareness

The widespread use of vitamin supplements, coupled with a general perception of safety, creates a unique public health challenge. Educational efforts must emphasize that while vitamins play a critical role in maintaining health, they are not without risks. This is particularly important in the context of brain health, where both deficiency and excess may contribute to cognitive impairment. Public messaging should move beyond blanket endorsements of supplementation and instead promote informed, individualized strategies guided by evidence and clinical oversight.

From a policy standpoint, regulatory agencies may need to revisit guidelines for supplement labeling and consumer education. Clearer information about tolerable upper intake levels, potential side effects, and the importance of laboratory monitoring could empower consumers to make safer choices. In clinical settings, incorporating questions about supplement use into routine assessments could help identify individuals at risk for nutrient-related cognitive issues. Ultimately, addressing the question of whether vitamins can cause dementia requires a multi-pronged approach that integrates research, education, and personalized care.

Vitamin D Dementia Research: Where Do We Go from Here?

The evolving literature on vitamin D and dementia underscores the importance of continued research. Longitudinal studies with large, diverse populations are needed to clarify the dose-response relationship and to identify subgroups who may benefit—or be harmed—by supplementation. Emerging areas of interest include the interaction of vitamin D status with genetic risk factors such as APOE4, as well as its effects on specific cognitive domains like executive function and working memory.

Advanced imaging and biomarker studies may also shed light on how vitamin D influences brain structure and function over time. For example, MRI data could reveal whether optimal vitamin D levels correlate with preserved hippocampal volume or reduced white matter lesions—both of which are indicators of cognitive resilience. In addition, research into the timing of supplementation—whether early intervention yields greater benefits—could inform guidelines for preventive care. As the field advances, it will be essential to translate findings into practical recommendations that balance potential benefits with the emerging risks.

Bringing the Conversation to the Clinical Frontline

Clinicians must navigate the evolving evidence base with discernment, offering patients nuanced guidance that reflects current knowledge without overstating the benefits or downplaying the risks. This includes helping patients interpret laboratory results, assess their dietary intake, and understand the potential implications of long-term supplement use. Given the proliferation of misinformation online, the role of the clinician as a trusted source of scientifically grounded advice has never been more important.

In discussing the question of whether vitamin D dementia connections exist, healthcare providers must emphasize the importance of individualized care. Not all patients with low vitamin D levels require high-dose supplements, and not all memory issues in older adults stem from nutrient imbalances. A comprehensive evaluation that includes medical history, cognitive assessment, and laboratory testing offers the best foundation for informed decision-making.

Frequently Asked Questions: Exploring the Complex Link Between Vitamins, Vitamin D, and Dementia

1. Are there specific populations more vulnerable to the cognitive risks associated with excessive vitamin intake?

Yes, older adults, individuals with chronic health conditions, and those on multiple medications are particularly vulnerable to adverse cognitive effects from excessive vitamin use. As people age, changes in liver and kidney function can impair vitamin metabolism and clearance, increasing the risk of toxicity. In these groups, even modest over-supplementation can exacerbate underlying neurovascular vulnerabilities. When asking, can vitamins cause dementia, the answer may vary depending on personal health context—especially for people already dealing with neurological disorders or metabolic syndrome. This is especially relevant for the vitamin D dementia connection, as older adults with limited sun exposure may inadvertently oversupplement without monitoring serum levels.

2. How do fat-soluble vitamins like vitamin D differ in dementia risk compared to water-soluble vitamins?

Fat-soluble vitamins, including vitamin D, A, E, and K, are stored in the body’s fat tissues and liver, meaning they can accumulate over time if taken in excess. This accumulation raises the risk of toxicity-related complications, some of which may mimic or exacerbate cognitive symptoms. In contrast, water-soluble vitamins like B-complex and C are generally excreted when taken in surplus, though they are not entirely risk-free either. The question can vitamins cause dementia becomes particularly salient with fat-soluble varieties due to their long half-life and persistent impact on calcium balance, inflammation, and oxidative stress in the brain. Specifically, vitamin D dementia interactions have shown that prolonged elevated levels may interfere with cerebrovascular integrity.

3. Could taking vitamin D supplements without lab testing increase dementia risk?

Absolutely. Self-prescribing high doses of vitamin D without routine lab monitoring can lead to serum levels that surpass the optimal range, potentially resulting in hypercalcemia and cognitive side effects. While many people take vitamin D for bone and immune health, few are aware of its nuanced relationship with brain function. When evaluating the concern—can vitamins cause dementia—unmonitored supplementation emerges as a recurring risk factor. For those taking supplements regularly, it’s crucial to have their 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels assessed by a healthcare provider at least annually. Maintaining appropriate vitamin D levels, especially in aging populations, may help avoid the cognitive complications observed in some vitamin D dementia studies.

4. Are there any early signs that vitamin D supplementation may be negatively affecting brain function?

Yes, early signs of adverse reactions to excessive vitamin D can include brain fog, memory lapses, irritability, and persistent fatigue. These symptoms often overlap with early cognitive decline, making them easy to overlook or misattribute. When patients present with such symptoms and have been using high-dose supplements, clinicians may need to consider whether the supplements themselves could be contributing to the problem. In some case reports exploring can vitamins cause dementia, patients improved cognitively once excessive supplementation was discontinued. It’s worth noting that vitamin D dementia concerns are not always about deficiency—sometimes excess is the hidden culprit.

5. What role does sun exposure play in balancing vitamin D levels for cognitive health?

Sunlight remains one of the most natural and efficient ways to synthesize vitamin D, as ultraviolet B (UVB) rays stimulate production in the skin. Unlike supplementation, endogenous production from sun exposure is self-regulating—once sufficient levels are reached, the body limits further synthesis. This makes moderate sunlight exposure a potentially safer alternative for maintaining vitamin D status without risking toxicity. When examining whether can vitamins cause dementia, it’s important to distinguish between natural and synthetic sources, especially as over-supplementation is more likely to lead to adverse outcomes. Encouraging sensible sun exposure could help balance the risks and benefits suggested by emerging vitamin D dementia research.

6. Can cognitive symptoms caused by vitamin excess mimic those of true dementia?

Yes, cognitive effects from vitamin toxicity can closely resemble early stages of dementia, including memory impairment, disorientation, and decreased problem-solving ability. However, one distinguishing feature is reversibility—when the excessive vitamin intake is discontinued, symptoms often improve within weeks or months. This presents a diagnostic challenge, especially in older adults where early dementia symptoms may be mistakenly attributed to aging alone. The growing body of literature exploring can vitamins cause dementia now includes clinical cases where supplement-induced cognitive decline was initially misdiagnosed as neurodegenerative disease. In particular, vitamin D dementia overlap has highlighted the need for thorough medication and supplement history in cognitive assessments.

7. Are there any known interactions between vitamin D and medications that affect cognitive function?

Vitamin D can interact with various medications, including corticosteroids, statins, antiepileptics, and some weight-loss drugs, potentially altering its metabolism or effectiveness. These interactions can either potentiate or diminish the effects of vitamin D, making dosing less predictable and increasing the risk of both deficiency and toxicity. For individuals already on cognitive-enhancing or psychiatric medications, these interactions may subtly influence mental clarity or exacerbate side effects. In the broader context of asking can vitamins cause dementia, drug-supplement interactions represent an underexplored mechanism by which unintended consequences could manifest. Researchers studying vitamin D dementia pathways increasingly advocate for integrated pharmacologic reviews before initiating long-term supplementation.

8. How do clinicians differentiate between vitamin-induced cognitive issues and progressive neurodegeneration?

Differentiating the two requires a multi-step clinical approach that includes serum nutrient testing, neurological evaluation, cognitive screening, and a careful review of supplement history. Progressive neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s typically show a pattern of steady decline, often confirmed by imaging or biomarkers, whereas vitamin-related cognitive symptoms may present suddenly and plateau or improve with intervention. Clinicians must ask not just what the patient is taking, but for how long and in what doses. As public awareness grows around questions like can vitamins cause dementia, clinical protocols are beginning to include vitamin screening panels in differential diagnosis. In some vitamin D dementia investigations, re-evaluation of patients previously diagnosed with early Alzheimer’s revealed reversible, supplement-related etiologies.

9. How might the gut-brain axis factor into the relationship between vitamin D and cognitive health?

Emerging research suggests that vitamin D plays a crucial role in gut microbiota composition, which in turn influences neuroinflammation, neurotransmitter production, and brain health. Disruptions to the gut-brain axis due to imbalanced vitamin D levels may contribute to mood disorders, cognitive fog, and long-term neurological risk. Although this is a relatively new field, it opens novel pathways for understanding how systemic imbalances can affect brain function indirectly. This raises further questions about the scope of the query can vitamins cause dementia, as mechanisms beyond direct neuronal impact are considered. The vitamin D dementia hypothesis may ultimately encompass microbiome modulation as an additional piece of the cognitive puzzle.

10. What future innovations could help minimize vitamin-related dementia risks?

Future innovations may include AI-powered nutrient tracking apps, wearable biosensors that monitor serum vitamin levels in real-time, and genetic testing to identify individuals who metabolize vitamins differently. Precision supplementation could become the norm, tailored to each person’s biology rather than relying on broad public health guidelines. Additionally, neuroimaging technologies may one day detect early brain changes linked to micronutrient imbalances, providing a warning system before cognitive symptoms appear. As our understanding deepens, tools designed to address the question can vitamins cause dementia will likely shift from reactive to preventive. Innovations grounded in personalized medicine will be key in balancing the benefits and risks suggested by ongoing vitamin D dementia research.

Conclusion: Navigating the Fine Line Between Benefit and Risk in Vitamin Supplementation for Brain Health

As the conversation around cognitive decline continues to evolve, the intersection of vitamin use and brain health commands increasing attention. The question “can vitamins cause dementia” is no longer purely academic—it is a real-world concern with clinical, personal, and public health implications. While the protective role of vitamin D against cognitive impairment remains a compelling area of research, evidence also suggests that excess intake may pose risks, especially when supplementation is pursued without medical guidance.

Understanding the nuanced relationship between vitamin D and dementia is essential for making informed health choices. Maintaining adequate—but not excessive—levels through safe sun exposure, diet, and monitored supplementation can support brain health without tipping into toxicity. Ultimately, the key lies in precision and personalization: tailoring vitamin use to individual needs, regularly assessing biochemical markers, and relying on evidence-based recommendations rather than trends or assumptions. In this way, we can honor the promise of nutritional science while safeguarding against its unintended consequences, ensuring that our pursuit of health does not inadvertently lead us down a path toward cognitive decline.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out.

Further Reading:

Vitamin D and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer disease

Brain vitamin D forms, cognitive decline, and neuropathology in community-dwelling older adults

Emerging the role of trace minerals and vitamins in Alzheimer’s disease

Disclaimer

The information contained in this article is provided for general informational purposes only and is not intended to serve as medical, legal, or professional advice. While Health11News strives to present accurate, up-to-date, and reliable content, no warranty or guarantee, expressed or implied, is made regarding the completeness, accuracy, or adequacy of the information provided. Readers are strongly advised to seek the guidance of a qualified healthcare provider or other relevant professionals before acting on any information contained in this article. Health11News, its authors, editors, and contributors expressly disclaim any liability for any damages, losses, or consequences arising directly or indirectly from the use, interpretation, or reliance on any information presented herein. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of Health11News.