Introduction: Debunking a Popular Myth with Scientific Precision

The question “Is the brain a muscle?” is surprisingly common, especially among those curious about optimizing cognitive performance and mental health. On the surface, it might sound like a simple anatomical query. However, beneath that question lies a much deeper inquiry into how the brain functions, how it strengthens over time, and how its condition relates to overall mental well-being. While the brain is not literally a muscle in the biological sense, the metaphor of training the brain like a muscle holds valuable truth. This article will explore the structural and functional distinctions between muscles and the brain, delve into how neuroplasticity parallels muscular growth, and explain why this analogy continues to shape public understanding of brain health. By the end of this in-depth exploration, readers will not only understand why the brain is not a muscle but also appreciate how its similarities to muscular development provide actionable insight into enhancing mental performance and resilience.

You may also like: Boost Brain Power Naturally: Evidence-Based Cognitive Training Activities and Memory Exercises That Support Long-Term Mental Health

Understanding Brain Anatomy: What Is the Brain Made Of?

To answer the question “Is the brain a muscle?” we first need to understand what the brain is made of. The human brain consists predominantly of neurons and glial cells, not muscle fibers. Neurons are specialized cells responsible for transmitting information through electrical and chemical signals. Glial cells, once thought to be mere support structures, are now understood to play critical roles in neuron maintenance, immune defense, and even modulating communication between neurons.

Muscles, by contrast, are composed of elongated fibers made from proteins such as actin and myosin. These fibers contract and relax in response to signals from the nervous system, producing movement. Muscles are vascular, responsive to mechanical stimuli, and structured to support physical exertion. The brain, on the other hand, is housed in the skull and cushioned by cerebrospinal fluid. It does not contract or expand in the same manner as muscles do, although blood flow and electrical activity fluctuate based on mental activity.

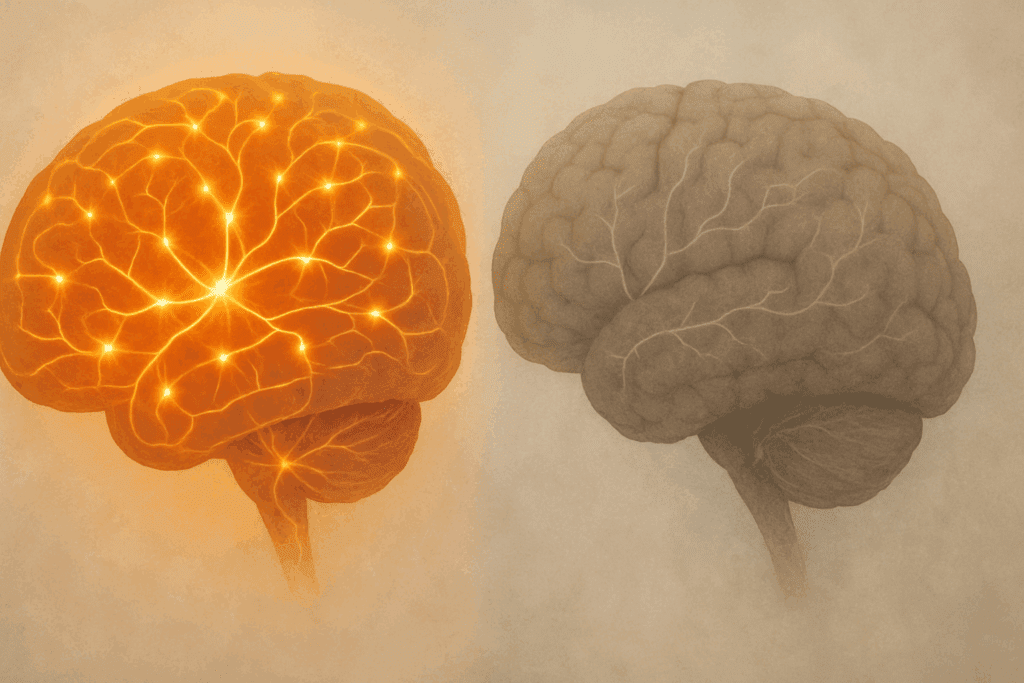

Thus, from a purely anatomical standpoint, the answer to “Is the brain considered a muscle?” is a definitive no. However, what makes the brain such a fascinating organ is that, much like a muscle, it can adapt, grow stronger, and become more efficient when properly challenged and stimulated.

The Concept of Neuroplasticity: The Brain’s Ability to Strengthen

While the brain is not a muscle, it exhibits a remarkable ability to change and adapt in response to experiences, much like muscles adapt to resistance training. This property is known as neuroplasticity. Neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s capacity to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections throughout life. This ability is foundational to learning, memory, recovery from injury, and adaptation to new situations.

Consider how a bodybuilder lifts weights to increase muscle mass and strength. In a similar fashion, mental exercises such as learning a new language, solving complex problems, or even practicing mindfulness meditation can stimulate the brain to form new neural pathways. These activities reinforce synaptic connections, making the brain more efficient and resilient over time.

It is through this lens that the metaphorical interpretation of the question “Is the brain a muscle?” begins to make sense. Although the brain and muscle tissue are fundamentally different, the way each can be trained and strengthened provides a powerful analogy that bridges neuroscience and personal development.

Exercise and the Brain: A Two-Way Connection

Interestingly, while the brain is not composed of muscle fibers, it plays a pivotal role in muscle function and, conversely, benefits profoundly from physical exercise. Research consistently shows that regular physical activity enhances brain function, boosts mood, and may even delay cognitive decline associated with aging.

Aerobic exercise, for example, has been shown to increase the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein that supports the growth and survival of neurons. BDNF is often likened to “fertilizer for the brain,” promoting synaptic plasticity and improving memory and learning capacity. Moreover, exercise improves blood flow to the brain, delivering oxygen and nutrients while removing waste products more efficiently.

This bidirectional relationship emphasizes that although the brain is not technically a muscle, it thrives under conditions that also support muscular health. Therefore, when people ask, “Is the brain considered a muscle?” they are often referring to this functional interplay between physical activity and cognitive strength.

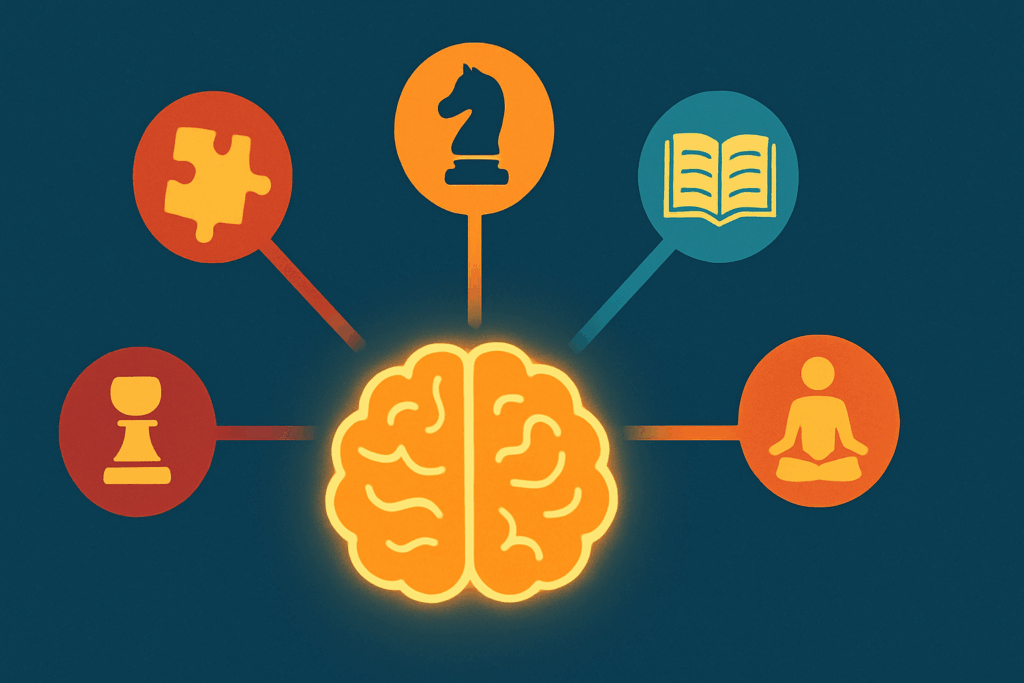

Training the Brain: Cognitive Workouts and Mental Fitness

Just as muscles grow with consistent resistance training, the brain benefits from regular cognitive challenges. Mental stimulation, often termed “cognitive training,” encompasses a wide range of activities designed to enhance intellectual performance and prevent mental stagnation. These activities include puzzle-solving, reading, strategic games, and even engaging in complex conversations.

One compelling example of this concept in action is the use of brain training programs in aging populations. Studies have shown that targeted mental exercises can improve processing speed, attention, and memory, even in individuals over the age of 70. The principles are similar to physical training: varied and progressively challenging tasks stimulate different brain regions, thereby enhancing overall mental fitness.

In this context, it’s understandable why so many people are drawn to the idea that the brain functions like a muscle. While not anatomically accurate, the metaphor encourages individuals to treat mental health with the same proactive attention often reserved for physical fitness.

Mental Health and Brain Resilience: Strength Beyond Structure

When considering the question “Is the brain a muscle?” it’s essential to address the broader implications for mental health. Mental resilience—the ability to cope with stress, adapt to change, and recover from adversity—is closely tied to brain function. Practices that support brain health, such as adequate sleep, balanced nutrition, social interaction, and stress management, play a crucial role in maintaining psychological well-being.

The brain’s prefrontal cortex, which governs executive functions like decision-making and emotional regulation, is particularly sensitive to chronic stress. Long-term exposure to stress hormones like cortisol can impair this region, reducing cognitive flexibility and increasing the risk of anxiety and depression. On the flip side, interventions like mindfulness meditation, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and physical exercise have been shown to reverse some of these effects, enhancing both structural and functional brain health.

The concept that one can “train” their brain for better emotional control and psychological endurance mirrors how athletes train for physical stamina. Thus, even though the answer to “Is the brain considered a muscle?” is technically no, the spirit of the analogy holds substantial truth in the context of mental health.

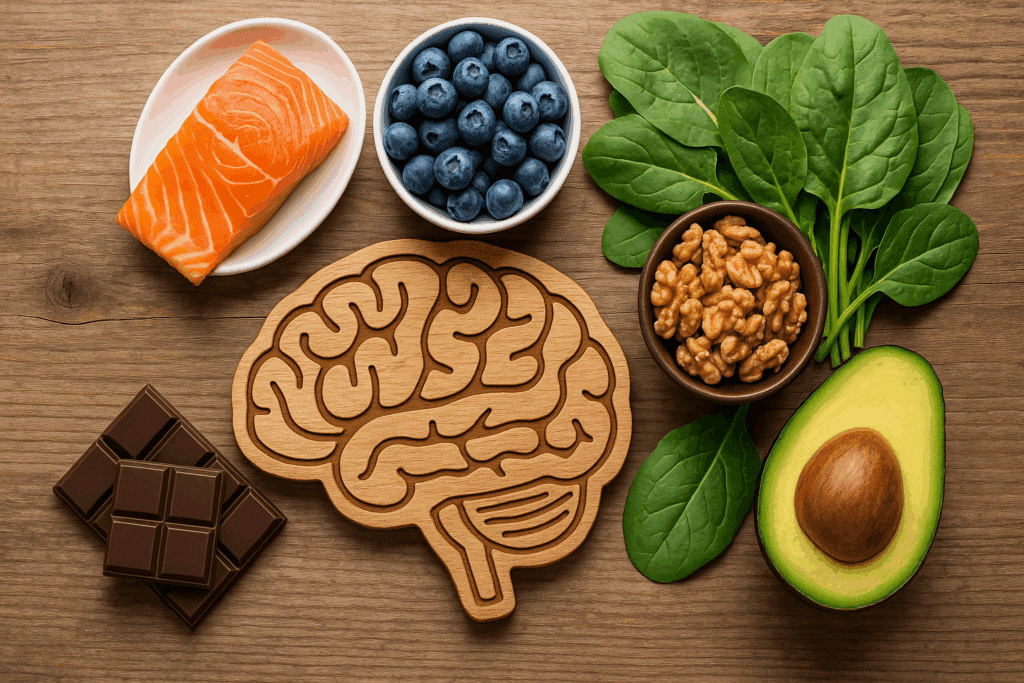

The Role of Nutrition in Brain Strength and Performance

Muscles require protein, electrolytes, and other nutrients to perform optimally, and so does the brain. Nutrition plays an irrefutable role in cognitive function, memory formation, and mood regulation. Specific nutrients—such as omega-3 fatty acids, B vitamins, and antioxidants—are particularly vital for maintaining brain health and supporting neuroplasticity.

Omega-3 fatty acids, found in fatty fish, flaxseed, and walnuts, are key components of neuronal membranes and facilitate efficient communication between brain cells. B vitamins support the production of neurotransmitters and energy metabolism, both of which are critical for sustaining mental clarity and focus. Antioxidants, like those found in berries and leafy greens, protect brain tissue from oxidative stress, a contributing factor in cognitive decline.

Understanding how diet influences cognitive health provides another layer of context to the metaphor of brain-as-muscle. Just as an athlete would not ignore nutrition when training for a marathon, individuals aiming to enhance mental performance must also consider dietary support as a cornerstone of brain health.

Sleep and Brain Recovery: The Restorative Parallel to Muscle Repair

Muscles require rest to recover and grow stronger, and the same is true for the brain. Sleep is not merely a passive state but an active period of restoration for cognitive systems. During sleep—particularly the deep, non-REM stages—the brain consolidates memories, clears out metabolic waste via the glymphatic system, and resets emotional regulation mechanisms.

Chronic sleep deprivation impairs attention, decision-making, and emotional stability. Over time, it can also increase the risk of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, as the brain’s ability to clear beta-amyloid plaques is compromised without adequate rest. Conversely, consistent high-quality sleep enhances problem-solving abilities, emotional intelligence, and overall mental resilience.

Here again, the metaphor of muscle recovery finds relevance. While the brain is not a muscle, its dependence on restorative cycles to function at its peak draws a strong parallel to the recovery needs of muscle tissue. So, when people ponder, “Is the brain a muscle?” the comparison extends into lifestyle considerations that are essential for long-term health and performance.

Cognitive Decline and Brain Aging: Preventive Approaches Rooted in Strength

Aging affects all biological systems, but the brain, much like muscles, can either deteriorate rapidly or maintain function, depending on how it’s treated over time. Cognitive decline is not an inevitable outcome of aging; rather, it is often a byproduct of neglecting brain-stimulating activities, poor lifestyle choices, or underlying health conditions.

Research has shown that lifelong learning, physical activity, social engagement, and proper management of conditions like hypertension and diabetes are all associated with better cognitive outcomes in older adults. Cognitive reserve—the brain’s ability to improvise and find alternative ways of completing tasks—is a concept that further supports this proactive approach. Like muscle mass built over time, cognitive reserve is developed through consistent mental activity and provides a buffer against age-related decline.

This is yet another reason the question “Is the brain considered a muscle?” persists. While the brain’s structure does not change like biceps do, its ability to retain performance through consistent effort mirrors the adaptive potential seen in muscular systems.

Why the Metaphor Matters: Shaping Public Understanding of Mental Health

In an era where mental health is finally receiving the attention it deserves, metaphors like “the brain is a muscle” serve as powerful tools for education and motivation. While not scientifically accurate in the literal sense, the phrase encapsulates the idea that brain health is not fixed and unchangeable—it can be nurtured, improved, and optimized with effort and intention.

Moreover, the metaphor encourages individuals to take proactive steps toward cognitive wellness, promoting practices like mental stimulation, physical exercise, mindfulness, and proper nutrition. These habits, though seemingly simple, have profound implications for mental health outcomes, productivity, and quality of life.

Therefore, even though the answer to “Is the brain a muscle?” remains no in anatomical terms, the conceptual value of treating the brain as something that can be “trained” continues to inspire health-conscious behaviors that yield real benefits.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Why do so many people think the brain is a muscle?

The belief that the brain is a muscle likely stems from the common comparison between brain training and physical training. When people engage in intellectually demanding tasks like solving puzzles, studying complex topics, or learning new languages, they often feel mental fatigue—similar to the muscle soreness that follows a workout. This shared experience encourages the metaphor, leading to the question: is the brain a muscle? However, this misconception also arises from a growing awareness of neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to rewire and improve with use, which parallels how muscles grow through resistance training. Even though the brain is not considered a muscle in anatomical terms, the analogy has taken root in educational and psychological contexts. Educators and cognitive scientists often use the comparison to encourage habits like repetition and focused practice, which are known to enhance memory and problem-solving. The idea that “you either use it or lose it” fits nicely with the muscle metaphor, reinforcing the misunderstanding but also promoting valuable behaviors for cognitive health. While it’s important to correct the biological error, the metaphor remains a powerful teaching tool when used with care and precision.

2. Can treating the brain like a muscle help in managing stress or anxiety?

Absolutely. Although the brain is not considered a muscle, the idea of training it for resilience has significant implications for mental health. Just as regular physical activity strengthens muscle endurance, consistent mental practices—like mindfulness, meditation, and cognitive-behavioral techniques—can enhance emotional regulation and stress response. When someone asks, “is the brain a muscle?”, the underlying concern often involves how to fortify the mind against psychological strain. Training the brain to recognize, reframe, and respond more calmly to stressful situations is akin to building psychological stamina. Research in neuropsychology supports this approach, showing that repeated exposure to mindful techniques alters the structure of the brain’s prefrontal cortex and amygdala, areas involved in emotion regulation. Therefore, while the brain is not a muscle in composition, treating it with similar principles of consistent, goal-directed training can reduce the impact of anxiety and increase a person’s ability to bounce back from adversity. Over time, these practices can rewire neural pathways, creating a more balanced and resilient mental state.

3. How does brain training differ from physical muscle training?

Despite the surface similarities between brain and muscle development, the two involve fundamentally different biological mechanisms. When we ask, is the brain a muscle, we must remember that muscles strengthen through hypertrophy—an increase in muscle fiber size due to physical stress and protein synthesis. In contrast, the brain strengthens through synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis, particularly in regions like the hippocampus. Activities like learning new skills, exploring unfamiliar environments, and engaging in complex thought processes help form new neural connections. Another key difference is that muscle repair happens primarily during physical rest, while the brain undergoes significant restructuring during sleep, especially during deep and REM stages. Though the brain is not considered a muscle, it thrives on a rich variety of stimuli—not just repetition, but novelty, emotional relevance, and environmental enrichment. Additionally, while overtraining a muscle can lead to strain or injury, cognitive overexertion manifests more subtly, often through burnout, mental fog, or reduced creativity. Understanding these differences is crucial for designing effective cognitive training routines. The metaphor holds motivational value, but strategies for brain enhancement should reflect the unique biological and psychological characteristics of our most complex organ.

4. Are there risks in thinking of the brain as a muscle?

Yes, there are potential pitfalls to oversimplifying the brain-muscle comparison. Although is the brain a muscle is a catchy phrase, taking it too literally can lead to unrealistic expectations about how quickly mental performance should improve with training. This misconception might also promote overuse without rest—just as overtraining muscles can lead to injury, the brain too, needs recovery periods, especially in the form of quality sleep and downtime. If someone believes the brain is considered a muscle, they may also overlook important cognitive differences, such as the brain’s need for emotional regulation, social connection, and creative expression. Overemphasis on linear progress and “mental gains” can foster a toxic productivity mindset, potentially exacerbating stress or burnout. Moreover, reducing the brain’s complexity to just a training model ignores its unique roles in identity, emotion, and consciousness. While using the muscle metaphor can inspire proactive mental habits, it must be balanced with a nuanced understanding of brain function. It’s more helpful to think of the brain as a dynamic system that benefits from stimulation, reflection, and rest in equal measure.

5. How can we “strengthen” the brain in ways that don’t mirror muscle workouts?

One of the most powerful ways to enhance brain health without directly mimicking muscle workouts is through social interaction and emotional engagement. Unlike muscles, which grow through mechanical stress, the brain responds to emotional relevance and novelty. Asking is the brain is a muscle encourages us to think in terms of structured reps and sets, but brain optimization often benefits from fluid, varied, and emotionally rich experiences. For example, storytelling, meaningful conversations, and artistic expression activate widespread neural networks and promote neuroplasticity. These activities also release feel-good neurotransmitters like dopamine and oxytocin, which support learning and memory consolidation. So while the brain is not considered a muscle, it responds robustly to joy, connection, and creative exploration—areas not traditionally associated with strength training. Engaging with diverse cultures, pursuing hobbies, and cultivating curiosity all foster mental agility in ways that traditional muscle-building routines cannot. To fully support cognitive vitality, we must look beyond drills and exercises to holistic experiences that fuel the brain’s complexity and emotional depth.

6. Could thinking the brain is a muscle influence how we approach aging?

The idea that the brain is a muscle may actually have beneficial implications for aging if it motivates people to adopt mentally stimulating lifestyles. Cognitive decline is often mistakenly viewed as an unavoidable part of aging, but emerging research shows that environmental enrichment, learning new skills, and maintaining strong social ties can help preserve brain function well into older age. If someone internalizes the belief that the brain is considered a muscle, they might be more inclined to pursue activities like language learning, music practice, or community engagement to stay mentally sharp. This shift in mindset reframes aging not as an inevitable decline but as an opportunity for neuroplastic growth. That said, it’s crucial to recognize that the brain also undergoes structural changes with age, such as reduced volume in certain regions and slower processing speed. These changes require adaptive strategies—not brute-force training. So while the brain-muscle metaphor may inspire lifelong learning, it should be tempered with realistic expectations and an understanding of the biological shifts that come with aging.

7. How do modern brain health technologies reflect the muscle metaphor?

Modern neuroscience and digital health tools often reflect the metaphor that the brain is a muscle by offering gamified, measurable cognitive training platforms. Apps like Lumosity, Peak, and Elevate are designed with the idea that just as lifting weights builds strength, doing brain games enhances memory, attention, and reasoning skills. These tools are popular because they promise structured, incremental improvement—a framework familiar to anyone who’s followed a fitness regimen. Although the brain is not considered a muscle, these technologies mimic the structure of a workout routine: warm-up levels, increasing difficulty, performance metrics, and feedback loops. More advanced technologies, such as neurofeedback and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), go a step further by directly interacting with brain activity, much like resistance bands or machines shape physical training. However, the efficacy of many of these tools varies, and not all claims are supported by robust science. Therefore, while the muscle metaphor helps make these tools accessible and engaging, users should apply a critical lens when evaluating their long-term benefits.

8. Does nutrition support the brain the same way it supports muscle growth?

While there are parallels between how nutrition supports muscles and how it supports the brain, the underlying needs differ significantly. For muscles, macronutrients like protein are essential for tissue repair and hypertrophy. In contrast, the brain relies heavily on micronutrients that support neurotransmitter production, membrane integrity, and oxidative protection. When someone wonders is the brain a muscle, they may assume that high-protein diets will also boost brainpower. However, nutrients like omega-3 fatty acids, choline, B vitamins, magnesium, and polyphenols are far more crucial for maintaining mental sharpness and emotional balance. For example, DHA (a type of omega-3) is a major structural component of the brain’s gray matter and influences synaptic plasticity. Antioxidants found in colorful fruits and vegetables help reduce inflammation and oxidative stress, both of which are linked to cognitive decline. Although the brain is not considered a muscle, it does require precise and consistent nutritional support—just not the same types of fuel emphasized in traditional bodybuilding. A brain-healthy diet is diverse, rich in plants, and low in inflammatory foods, aligning more with Mediterranean or MIND-style eating patterns.

9. How does sleep affect the brain differently than it does muscles?

Sleep plays a restorative role for both the brain and muscles, but its impact on cognitive function is more multifaceted. Muscles recover during sleep primarily through hormonal processes like growth hormone release, which repairs microtears in muscle fibers. When asking is the brain a muscle, it’s important to consider that the brain doesn’t require mechanical repair in the same way. Instead, the brain uses sleep as a time for metabolic cleanup via the glymphatic system, emotional processing, and memory consolidation. Deep sleep (non-REM) is especially critical for clearing waste proteins like beta-amyloid, which are associated with Alzheimer’s disease when they accumulate. REM sleep, meanwhile, is key for emotional regulation and creative problem-solving. Sleep deprivation impairs functions unique to the brain, such as attention, reasoning, and emotional resilience—capabilities not directly tied to muscular performance. So while the brain is not considered a muscle, it relies even more heavily on quality sleep for optimal function, suggesting that cognitive rest may be more complex and essential than physical rest in many ways.

10. Can overtraining the brain cause harm like overtraining muscles can?

Yes, cognitive overtraining—though less visible than physical strain—can lead to mental fatigue, decreased focus, and emotional dysregulation. People who believe the brain is a muscle may mistakenly apply the same no-pain-no-gain philosophy to their intellectual or professional life. This approach can backfire, especially when it neglects rest, play, and emotional well-being. Unlike muscle overuse, which typically results in soreness or injury, brain overuse shows up as burnout, irritability, memory issues, and reduced problem-solving capacity. Chronic stress or mental overload also disrupts neurotransmitter balance and impairs neural plasticity. While the brain is not considered a muscle, it does respond to overexertion with consequences that can be just as serious—if not more insidious—than physical injury. Strategies for preventing cognitive burnout include practicing strategic rest, engaging in creative outlets, and setting boundaries between technology and work. In this sense, respecting the brain’s need for restoration is just as important as challenging it through mental workouts. Just like muscles, the brain thrives on a rhythm of effort and renewal.

Conclusion: Is the Brain a Muscle? A Metaphor Rooted in Science and Wellness

Ultimately, the question “Is the brain a muscle?” serves as both a scientific inquiry and a metaphorical springboard into a broader understanding of cognitive health. While the brain is not made of muscle tissue and functions in fundamentally different ways, it shares with muscles a remarkable capacity for growth, adaptation, and resilience when challenged and cared for properly.

Understanding that the brain is not a muscle—but behaves like one in many functional respects—can reshape how we approach mental fitness. Through cognitive training, physical activity, proper nutrition, quality sleep, and emotional resilience strategies, individuals can take meaningful control over their mental well-being. This empowerment is critical in a time when mental health challenges are widespread and often misunderstood.

So, while anatomically, the brain is not considered a muscle, treating it with the same diligence, respect, and strategic care as we would any other vital system in the body is both wise and essential. In doing so, we honor the complexity of the brain while leveraging practical strategies that enhance its function and support long-term mental health. In this way, the metaphor serves not just as a figure of speech but as a guiding principle for lifelong cognitive vitality.

Further Reading:

What Is the Physical Composition of the Human Brain?

People Say The Brain Is A “Muscle”. Turns Out, It’s Kind Of True