The trajectory of dementia is typically thought of as slow and insidious, marked by gradual decline in memory, reasoning, and daily functioning. However, for some individuals, the progression is anything but slow. Families and caregivers may find themselves alarmed when a loved one with dementia suddenly declines, seemingly overnight. This phenomenon—the sudden worsening of dementia symptoms—can be distressing and disorienting. It raises critical questions: Can dementia come on suddenly? What makes dementia worse? And how fast can dementia come on in those already diagnosed? In this comprehensive exploration, we delve into the causes, medical explanations, and implications of rapid changes in cognitive function, providing clarity and guidance through the lens of expert insight and medical science.

You may also like: How to Prevent Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease Naturally: Expert-Backed Strategies to Reduce Your Risk Through Lifestyle and Diet

Understanding Progressive Dementia and Its Typical Course

Dementia, by definition, is a progressive neurological condition characterized by a decline in cognitive abilities that interferes with daily life. Progressive dementia involves a slow but steady decline over time. The stages of Alzheimer disease, the most common form of dementia, often unfold over several years, from mild forgetfulness to profound confusion and loss of independence. Other types of dementia, such as vascular dementia, frontotemporal dementia, and Lewy body dementia, follow different patterns but generally adhere to this chronic, progressive arc.

Despite this, the speed and manner of decline can vary greatly between individuals. Factors such as co-existing medical conditions, lifestyle habits, and genetic predisposition influence how quickly symptoms escalate. Understanding the typical patho of dementia helps clinicians and caregivers distinguish between expected progression and sudden changes that may indicate a reversible or treatable cause. When someone experiences a sharp downturn in cognition or function, it may not be due solely to the underlying senile degeneration of the brain but could also reflect secondary issues requiring immediate attention.

Can Dementia Happen Suddenly? Exploring Rapid Onset and Its Red Flags

One of the most pressing concerns for families is whether dementia can happen suddenly. In most cases, the answer is no. Dementia is considered a chronic condition, not an acute event. Yet the perception of sudden onset is not uncommon. In situations where signs of rapid onset dementia appear, they may reflect the culmination of previously unnoticed symptoms rather than a truly abrupt emergence. Alternatively, the sudden appearance of cognitive deficits could signify delirium, a separate but often conflated condition that mimics dementia.

Delirium is characterized by an acute and fluctuating disturbance in attention and awareness, often triggered by infection, medication side effects, metabolic imbalances, or hospitalization. In older adults, especially those with pre-existing cognitive impairment, delirium can mask itself as an advanced stage of dementia. Differentiating between delirium and progressive dementia is vital because delirium is frequently reversible if the underlying cause is addressed.

For those already diagnosed, families may still ask: does dementia come on suddenly, or does dementia happen suddenly again in later stages? In the context of existing cognitive decline, sudden changes often indicate an exacerbation due to an external factor. Understanding this distinction helps prevent mislabeling treatable conditions as inevitable progression.

Signs of Advanced Dementia and the Threshold of Stage 5 Symptoms

As dementia advances, its impact becomes more profound and more apparent. Stage 5 dementia symptoms typically involve significant memory loss, disorientation, and difficulty performing activities of daily living such as dressing, cooking, or managing finances. At this stage, individuals may forget their address or phone number, become confused about the date or location, and require help choosing appropriate clothing for the season.

What stage of dementia is losing track of time? This is often first observed in middle stages but becomes especially pronounced in stage 5 and beyond. The signs of advanced dementia include behavioral changes, emotional instability, and diminished insight. One hallmark of the late stages of dementia symptoms is the loss of verbal abilities and recognition of loved ones. For caregivers, these changes are emotionally taxing and can seem to arrive suddenly, especially when compounded by health issues like infections or dehydration.

Understanding these milestones within the stages of Alzheimer disease provides a framework for anticipating needs and planning care. It also assists clinicians in differentiating between normal progression and sudden worsening of dementia symptoms due to external complications.

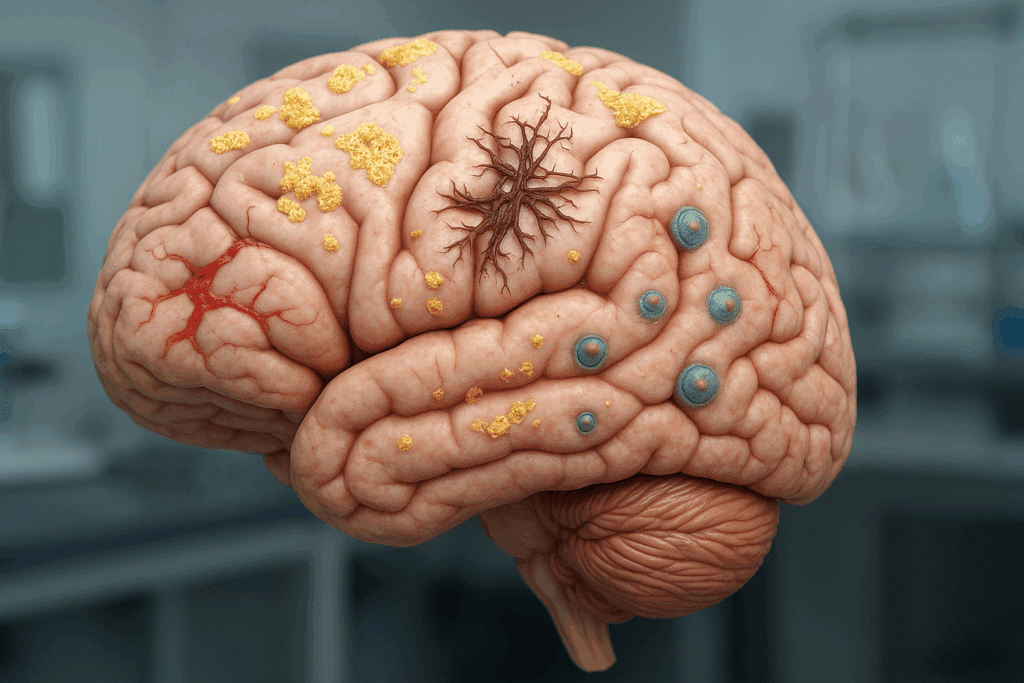

What Happens to the Brain with Dementia: Medical Mechanisms of Degeneration

The physical basis of dementia lies in neurodegeneration—the progressive loss of structure and function of neurons. In Alzheimer’s disease, this includes the accumulation of beta-amyloid plaques and tau protein tangles, which disrupt communication between nerve cells and trigger inflammation. In vascular dementia, damage arises from reduced blood flow due to strokes or chronic small vessel disease. Frontotemporal dementia involves the atrophy of the frontal and temporal lobes, while Lewy body dementia includes protein deposits known as Lewy bodies.

The common denominator in these disorders is the senile degeneration of the brain, a phrase encompassing the cumulative, irreversible damage that erodes memory, judgment, and personality. Senile degeneration of the brain causes deterioration in multiple brain systems, eventually impairing motor function, speech, and even swallowing. This biological understanding is essential to grasp the patho of dementia, as it frames symptoms not as random behaviors but as the result of identifiable neurological breakdowns.

When caregivers notice a sudden cognitive shift, it is crucial to ask: what can cause rapid onset dementia in someone already declining? Often, such episodes are due to superimposed factors that exacerbate the underlying disease. A urinary tract infection, for example, may cause confusion and hallucinations in someone with mild dementia, mimicking a leap into late-stage impairment.

Can Dementia Come and Go? Intermittent Symptoms and Their Misinterpretation

Another perplexing phenomenon is the apparent variability in symptoms. Some days may seem better than others, leading families to wonder: can dementia come and go? This is a complex question. In true progressive dementia, cognitive function does not improve permanently. However, fluctuations can and do occur, especially in dementia types like Lewy body dementia or those compounded by delirium or mood disorders.

These shifts may lead to misinterpretation. One day, the individual might engage in a lucid conversation; the next, they are disoriented and unable to follow simple directions. Such changes often reflect underlying issues—fatigue, dehydration, or even changes in routine. These dementia episodes should not be dismissed as benign, as they may signal the need for medical evaluation. If left unaddressed, episodic fluctuations can contribute to faster overall decline.

Understanding what are the signs dementia is getting worse is vital. These include a noticeable drop in ability to complete routine tasks, increasing dependence on caregivers, reduced comprehension, and worsening incontinence. Recognizing that cognitive regression can occur in leaps rather than gentle slopes underscores the need for vigilance.

Complications for Dementia: Medical, Psychological, and Social Dimensions

The complications for dementia are multifaceted, encompassing both medical and psychosocial challenges. Physically, individuals are prone to infections, falls, malnutrition, and adverse drug reactions. Psychologically, they may experience depression, anxiety, or paranoia, which further complicates care. Socially, families may encounter isolation, caregiver burnout, and difficult decisions about institutionalization.

Sudden worsening of dementia symptoms can often be linked to one of these complications. For instance, medication changes or polypharmacy can provoke cognitive shifts. Similarly, hospitalization—even for unrelated reasons—can lead to disorientation and persistent decline. Knowing how fast dementia can come on in the face of these triggers allows healthcare teams to anticipate and mitigate risk.

Importantly, not all observed declines are caused by dementia itself. Which of the following is not a cause of dementia? The answer includes conditions such as depression, vitamin deficiencies, thyroid disorders, and delirium—all of which can produce dementia-like symptoms but are potentially reversible. A thorough diagnostic workup is essential, especially when decline appears abrupt or atypical.

The Role of Medical Terminology and Diagnostic Accuracy in Dementia Care

In navigating dementia, both laypeople and professionals must contend with complex dementia medical terminology. Terms such as “executive dysfunction,” “apraxia,” or “semantic memory” can be confusing. Yet understanding this vocabulary helps facilitate more precise communication and tailored care. For example, distinguishing between apathy and depression can guide appropriate treatment strategies.

Similarly, clarity around terms like “advanced dementia symptoms” or “late stages of dementia symptoms” enables caregivers to prepare for end-of-life transitions, including palliative care and hospice considerations. In medical contexts, precision is key. When physicians refer to the senile degeneration of the brain, they are identifying a global deterioration rather than attributing symptoms to a singular cause. This broader framing promotes holistic intervention.

Clinicians are also tasked with recognizing stage-specific needs. Knowing what stage of dementia is losing track of time enables anticipatory guidance and timely intervention. Each marker along the spectrum of disease progression has implications for safety, autonomy, and quality of life.

What Makes Dementia Worse: Triggers of Accelerated Decline

Several factors can hasten the decline in someone with dementia. These include physical health issues such as infections, metabolic imbalances, pain, and sensory deprivation. Social stressors like isolation, loss of routine, and caregiver stress also play a role. Environmental disruptions—like moving to a new home or transitioning into a care facility—can precipitate sudden downturns.

Understanding what makes dementia worse is essential for prevention. For instance, untreated hearing loss has been linked to faster cognitive decline. Similarly, chronic sleep deprivation and poor nutrition can worsen symptoms. Even seemingly benign events, such as a minor surgical procedure, can unmask significant deficits in individuals whose cognitive reserve is already fragile.

Recognizing how fast dementia can come on in response to these insults emphasizes the importance of proactive care. Regular monitoring, clear communication among caregivers and clinicians, and a comprehensive health management plan can reduce the risk of acute deteriorations.

Frequently Asked Questions: Understanding Sudden Dementia Decline and Advanced Brain Degeneration

1. What distinguishes the sudden worsening of dementia symptoms from regular cognitive decline?

The sudden worsening of dementia symptoms typically involves an abrupt change in cognition or behavior that deviates from the person’s usual trajectory. Unlike the slow, steady decline seen in progressive dementia, these episodes often suggest an acute trigger such as infection, medication interaction, or environmental stress. Such abrupt changes can be confused with accelerated senile degeneration of the brain but often stem from modifiable causes. Importantly, rapid changes might not reflect the natural patho of dementia but instead hint at treatable underlying conditions. Understanding this distinction helps prevent misattributing reversible issues to irreversible advanced dementia symptoms.

2. Can dementia come on suddenly in someone with no prior history of cognitive issues?

While it may appear that dementia comes on suddenly, true dementia develops gradually over time. What may seem like a sudden onset is often the result of unnoticed early symptoms becoming more pronounced due to a triggering event. In many cases, what can cause rapid onset dementia includes head trauma, infection, stroke, or toxic exposure. These factors can cause a sharp cognitive decline that resembles dementia but may represent other conditions like delirium. Thus, when caregivers ask whether dementia can happen suddenly or whether it does dementia happen suddenly without prior signs, the answer is usually more complex and warrants thorough medical evaluation.

3. How can families recognize early signs of rapid onset dementia that might otherwise be missed?

Subtle behavioral changes, confusion with routine tasks, and increased emotional volatility are often overlooked as part of aging. However, these can be signs of rapid onset dementia, especially if they emerge over weeks or days. Monitoring speech patterns, motor coordination, and sleep disturbances can help detect early signs that progressive dementia is accelerating. These signs often precede sudden worsening of dementia symptoms and should prompt timely medical consultation. Understanding the nuanced stages of Alzheimer disease also assists families in spotting deviations from typical progression patterns.

4. What are some overlooked complications for dementia that may hasten decline?

Among the lesser-known complications for dementia are untreated dental infections, sensory deprivation, and dehydration—all of which can precipitate cognitive deterioration. Emotional stress, environmental overstimulation, and even seasonal affective disorder can accelerate the patho of dementia. Additionally, a lack of social interaction has been shown to exacerbate the senile degeneration of the brain in vulnerable individuals. Caregivers should also watch for subtle signs such as diminished appetite or reluctance to engage socially, which may indicate that late stages of dementia symptoms are beginning to surface. Awareness of these factors helps prevent rapid and often avoidable declines.

5. Is there a specific stage at which dementia symptoms tend to escalate more quickly?

Yes, stage 5 dementia symptoms often mark a pivotal point in disease progression where individuals lose the ability to manage daily tasks independently. This stage typically involves more significant memory gaps, increased confusion, and difficulty with personal hygiene. What makes dementia worse at this stage can include infections, relocation, and abrupt changes in routine. Caregivers often notice that what happens to the brain with dementia at this stage includes reduced metabolic function in key brain areas, further intensifying symptoms. Recognizing what stage of dementia is losing track of time helps anticipate safety and support needs.

6. Does dementia medical terminology help families better manage care decisions?

Yes, becoming familiar with dementia medical terminology empowers caregivers to communicate more effectively with clinicians and advocate for loved ones. Terms like “executive dysfunction” and “semantic memory loss” provide insight into specific cognitive deficits, offering clarity about what are the signs dementia is getting worse. Understanding such language also helps differentiate between conditions like delirium and true progressive dementia. Accurate use of terms relating to dementia pathophysiology allows for better planning and realistic expectations. It demystifies the illness and enables families to grasp the trajectory of senile degeneration of the brain.

7. How fast can dementia come on after a triggering event, such as surgery or infection?

The speed at which symptoms emerge after a trigger can be alarming. Infections like pneumonia or urinary tract infections can cause a marked decline within hours to days in someone with dementia. Similarly, post-operative delirium may resemble sudden dementia episodes and may persist for weeks. How fast does dementia come on in these cases is influenced by overall brain health, medication tolerance, and the presence of pre-existing cognitive impairment. Differentiating between delirium and signs of advanced dementia is essential to prevent mismanagement and missed opportunities for recovery.

8. Can dementia come and go, or is fluctuation a sign of another issue?

Cognitive fluctuations can occur in some types of dementia, particularly Lewy body dementia. However, when families ask “can dementia come and go,” it often reveals underlying confusion between dementia and delirium. Temporary improvements or regressions may be tied to environmental stimuli, medication timing, or caregiver interaction rather than changes in the disease itself. If symptoms dramatically improve or worsen within short periods, this might not align with progressive dementia but could indicate another reversible condition. Fluctuation should always prompt reassessment rather than passive observation.

9. What are some under-recognized senile degeneration of the brain causes that could guide prevention?

Emerging research suggests that chronic inflammation, poor cardiovascular health, and environmental toxins play more significant roles in senile degeneration of the brain causes than previously understood. These factors may not only accelerate the patho of dementia but also contribute to a higher likelihood of sudden worsening of dementia symptoms. Prevention efforts that target these areas, such as anti-inflammatory diets and regular cardiovascular screenings, may slow the transition into advanced dementia symptoms. Moreover, air pollution and pesticide exposure are being studied as potential long-term contributors to brain aging. Addressing these modifiable risks offers hope for delaying the onset of late stages of dementia symptoms.

10. Which of the following is not a cause of dementia, and why is this question clinically relevant?

Understanding which of the following is not a cause of dementia is vital in distinguishing treatable from irreversible conditions. Common misdiagnoses include vitamin B12 deficiency, hypothyroidism, and severe depression—all of which can mimic the cognitive decline seen in dementia. These conditions do not stem from senile degeneration of the brain but can present similar symptoms, especially in older adults. Identifying them early can prevent mislabeling someone with progressive dementia and instead offer a path to recovery. This clinical discernment can prevent unnecessary institutionalization and improve quality of life significantly.

Final Reflections on Brain Health: Navigating the Storm of Sudden Dementia Decline

When facing the sudden worsening of dementia symptoms, families and clinicians alike are thrust into a storm of uncertainty. Yet understanding what happens to the brain with dementia provides a compass. It illuminates the path from subtle memory lapses to advanced dementia symptoms, guiding decisions about care, safety, and quality of life. This understanding underscores that while progressive dementia is an unrelenting condition, not all declines are irreversible.

Knowing the signs of rapid onset dementia, the complications for dementia, and what stage of dementia is losing track of time allows for timely, evidence-based intervention. Recognizing whether sudden changes are due to the patho of dementia or external factors may make the difference between treatable episodes and permanent regression.

Ultimately, maintaining vigilance and staying informed can help caregivers anticipate challenges and respond with clarity. The question isn’t simply “can dementia happen suddenly” but rather, “how can we respond effectively when dementia appears to worsen overnight?” As research into dementia pathophysiology advances, so too does our ability to support those living with this complex condition. From understanding senile degeneration of the brain causes to navigating the nuances of dementia episodes, informed care grounded in compassion and medical insight remains our strongest ally.

In the end, we are reminded that dementia does not occur in isolation. It reflects the interconnectedness of biological, environmental, and emotional factors. As such, addressing the sudden worsening of dementia symptoms requires a multidimensional approach—one that honors the dignity of those affected while empowering caregivers to act with confidence and understanding.

Further Reading:

Sudden worsening of dementia symptoms

Rapidly progressive dementias — aetiologies, diagnosis and management