In a world where longevity is increasing and the population is aging, understanding the nuances between various types of cognitive decline is more important than ever. Among the most commonly misunderstood conditions are mild cognitive impairment and dementia. These terms are often used interchangeably in casual conversation, yet they signify distinct stages and forms of cognitive deterioration. For those concerned with brain health and the long-term impacts of aging, differentiating between mild cognitive impairment vs dementia is critical. Not only do these conditions affect memory, attention, and executive function, but they also carry implications for future risk, lifestyle interventions, and medical care. This article aims to provide a comprehensive exploration of what these conditions mean, how they are diagnosed, and what the brain changes signify for ongoing cognitive well-being.

You may also like: How to Prevent Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease Naturally: Expert-Backed Strategies to Reduce Your Risk Through Lifestyle and Diet

Defining Mild Cognitive Impairment: Early Signs and Clinical Meaning

Mild cognitive impairment, often abbreviated as MCI, is a condition that bridges the gap between normal age-related cognitive changes and the more severe decline seen in dementia. Clinicians often describe it as a mild neurocognitive disorder, representing a detectable but not yet debilitating shift in mental performance. When discussing what is mild cognitive impairment, it is essential to note that MCI does not interfere significantly with daily activities, although affected individuals may notice increased forgetfulness, difficulty concentrating, or slower thinking. These changes are usually subtle but persistent enough to be measurable through neuropsychological testing.

The MCI acronym in medical literature refers to a condition with varied etiology. While it may be a precursor to neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, it can also arise from sleep disorders, depression, or vascular issues. This variability makes understanding what causes cognitive impairment especially complex. Still, identifying MCI early opens the door to proactive interventions. The cognitive impairment definition used in clinical settings emphasizes a noticeable decline from a previous level of functioning, distinct from normal aging, yet insufficient to meet the dementia definition. It is precisely this threshold—between benign forgetfulness and more serious decline—that defines the unique character of mild cognitive impairment.

Understanding Dementia: Meaning, Definition, and Diagnostic Criteria

To understand the implications of MCI, one must first ask, what is dementia? The dementia definition is broader and more functionally significant than that of MCI. Dementia is not a single disease but a syndrome characterized by the progressive loss of cognitive functions severe enough to interfere with social and occupational life. When asking what does dementia mean clinically, it involves impairments in at least two areas of cognition—often memory and executive function—alongside other domains such as language, visuospatial abilities, and personality. Unlike MCI, dementia implies a significant loss of independence.

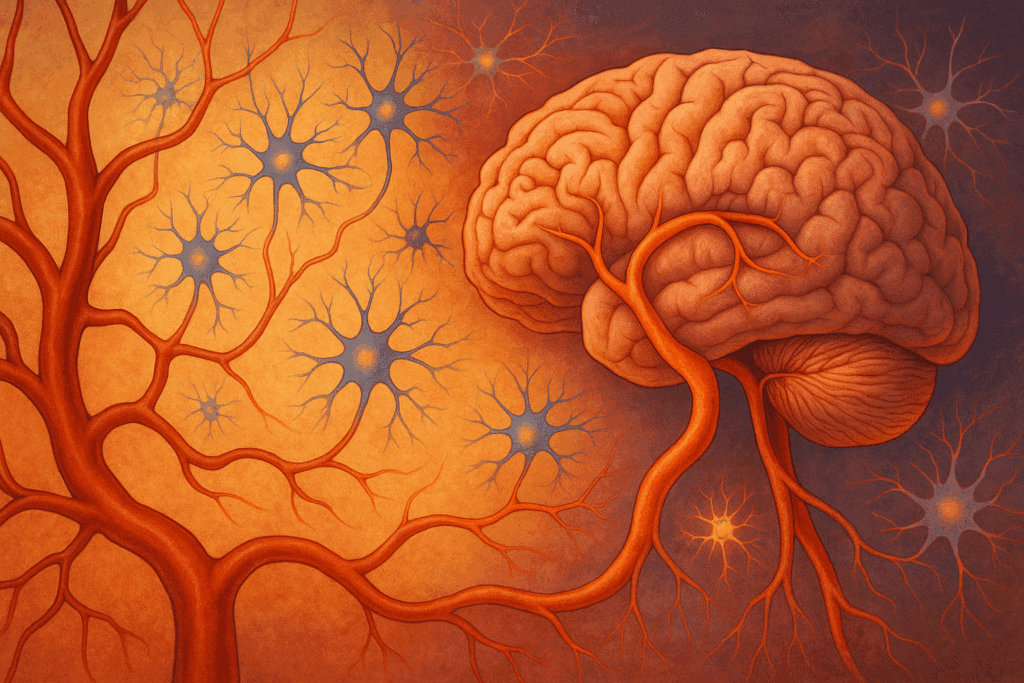

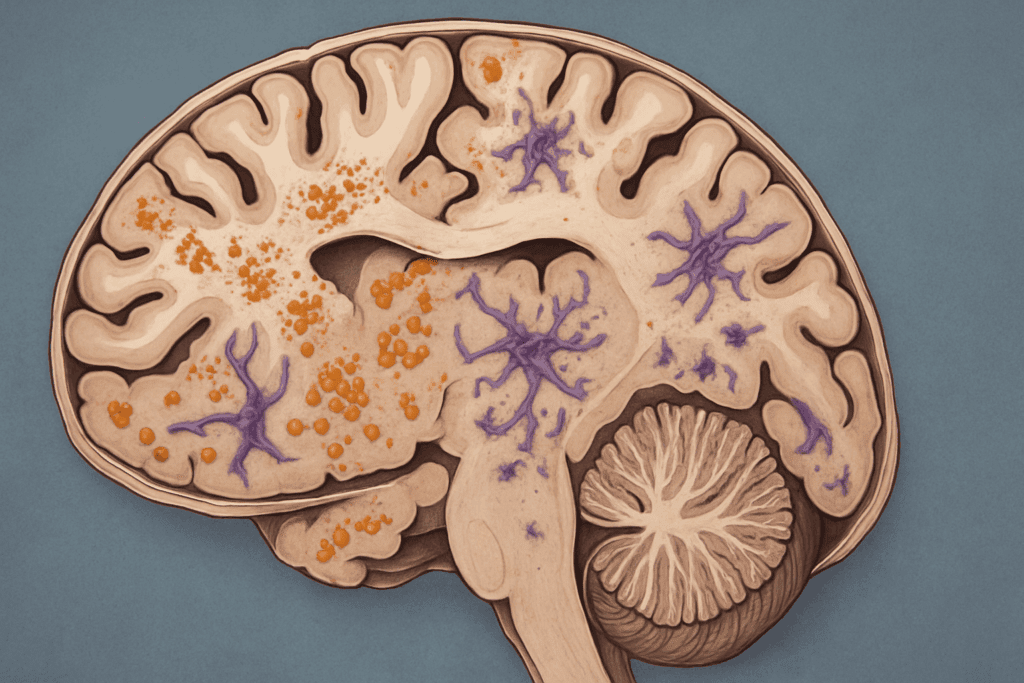

In terms of diagnosis, physicians look for persistent and worsening symptoms that cannot be explained by other mental health or systemic conditions. The dementia brain is characterized by distinct pathological changes, including amyloid plaques, tau tangles, vascular damage, or Lewy body inclusions, depending on the specific subtype. These structural changes result in disrupted neural connectivity and atrophy in brain regions associated with memory, emotion, and reasoning. It is important to understand that while dementia is often linked to aging, it is not an inevitable consequence of growing older. In answering the question, “is dementia a disease,” the answer lies in its classification: dementia is a clinical syndrome caused by a variety of diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, and others.

Key Differences Between Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia

The distinctions between mild cognitive impairment vs dementia are nuanced but clinically significant. While both involve cognitive decline, the primary difference lies in the impact on daily functioning. Individuals with MCI may experience frustration at their lapses but remain largely capable of managing daily routines. By contrast, those with dementia often require assistance with activities such as managing finances, medication schedules, or even basic self-care.

Cognitive impairment symptoms also differ in intensity and scope. With MCI, forgetfulness may center around names, appointments, or word-finding difficulties. These issues are often compensated for with reminders or increased effort. In dementia, the cognitive loss is more profound, extending into confusion about time and place, trouble recognizing familiar faces, or difficulty following a conversation. This distinction underlines the importance of understanding cognitive impairment vs dementia in both clinical practice and caregiver education.

From a diagnostic standpoint, biomarkers and imaging can offer insight into the progression of brain changes. While both groups may show hippocampal atrophy or other signs of neuronal loss, the patterns in dementia are more extensive. For instance, Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia, is marked by widespread cortical thinning and synaptic degeneration. This anatomical evidence reinforces the necessity of distinguishing MCI and dementia not merely as different labels but as different stages of cognitive disease progression.

Underlying Causes: What Brings On Dementia and Cognitive Impairment?

Understanding what causes dementia and related cognitive issues requires an appreciation of the multiple pathways that lead to neuronal dysfunction. The etiology of dementia is often multifactorial, including genetic predispositions, cardiovascular risk factors, and neuroinflammatory processes. Common diseases that cause dementia include Alzheimer’s, vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Each of these diseases presents a unique constellation of symptoms and brain changes, yet all converge on the final outcome of disrupted cognition and daily function.

Similarly, the causes of mild cognitive impairment are diverse. In some cases, MCI may be the early expression of a disease like Alzheimer’s. In others, it may result from chronic stress, sleep apnea, or metabolic imbalances. Some reversible contributors to cognitive difficulties include vitamin deficiencies, especially B12, or thyroid dysfunction. Thus, identifying what diseases cause dementia and what causes mild cognitive impairment requires a holistic approach that includes medical history, imaging, blood work, and neurocognitive testing.

A key clinical question is whether MCI will inevitably progress to dementia. While many individuals with MCI do eventually develop dementia, some remain stable for years or even recover, particularly when secondary causes are identified and treated. This variability highlights the importance of early diagnosis and intervention in preserving brain function over time.

The Role of the Brain: How Cognitive Loss Reflects Neurological Change

Brain imaging and pathology provide crucial insights into how these conditions affect neural structures. The dementia brain, for example, often shows significant shrinkage in the hippocampus, parietal lobes, and temporal cortex. These areas govern memory, spatial orientation, and language—functions commonly impaired in dementia. Structural MRI or PET scans can reveal amyloid and tau burden, offering visual confirmation of disease processes at work.

In contrast, the brain of someone with mild cognitive impairment may show subtler changes. While atrophy is often present, it is generally less pronounced. White matter lesions may be visible in those with vascular contributions to their MCI, suggesting a link between small vessel disease and early cognitive decline. Understanding what is cognitive loss on a biological level allows clinicians to make more informed treatment decisions.

The question of what is mild cognitive disorder overlaps with discussions about early-stage dementia, but the term also encompasses broader dysfunctions that do not yet reach the dementia threshold. The mci disease model suggests a transitional phase in which the brain is compensating for initial damage. Functional imaging studies reveal that individuals with MCI may show increased activation in certain brain regions during memory tasks, indicating neural compensation. These adaptive changes can delay the onset of more severe symptoms, particularly when supported by cognitive training, physical exercise, and healthy diet.

Medical Definitions and Diagnostic Frameworks: Clarifying the Terms

The medical literature is replete with terminology that can be confusing to the layperson. For instance, understanding what is MCI in medical terms requires clarity on both clinical presentation and neuropsychological assessment. MCI is typically diagnosed when cognitive difficulties are reported by the individual or observed by others, confirmed by standardized testing, and not severe enough to impair independence. The mci acronym medical definition specifically refers to a condition distinct from both normal aging and dementia.

Similarly, the term mild neurocognitive disorder, as defined in the DSM-5, aligns closely with the clinical concept of MCI. It is important to recognize that these diagnostic labels are not just semantic distinctions; they shape treatment planning, insurance coverage, and patient expectations. Asking what is MCI disease may seem redundant, but it reflects a need for clarity around the transitional nature of this diagnosis.

The question of which of the following best describes the meaning of dementia often arises in exams and educational materials. The most accurate answer emphasizes its status as a syndrome involving chronic, progressive loss of multiple cognitive domains. This understanding is central to distinguishing dementia from reversible conditions and from less severe impairments like MCI.

Recognizing the Early Signs: Symptoms and Progression

Spotting early cognitive impairment symptoms is a vital part of timely intervention. These signs may include forgetting recent conversations, misplacing items more frequently, or having trouble planning complex tasks. While these symptoms may seem benign, they can signal the beginning of significant changes in brain function. Differentiating between what is cognitive difficulties and what constitutes a diagnosable condition like MCI or dementia is often challenging without professional assessment.

The progression from MCI to dementia is not linear. Some individuals experience rapid decline, while others plateau or even improve. Factors influencing this trajectory include genetic risk, lifestyle habits, comorbid conditions, and psychological resilience. For example, physical inactivity and social isolation are known to exacerbate cognitive loss, while mental stimulation and strong social ties may offer protective effects.

Public awareness around what is cognitive impairment and what is cognitive loss remains limited, even as these conditions become more common. Media portrayals often blur the line between forgetfulness and debilitating disease, making it harder for individuals and families to know when to seek help. Education around the distinctions between MCI and dementia can empower patients to advocate for appropriate screening and care.

Cultural and Linguistic Considerations: Defining Dementia Across Borders

An often-overlooked aspect of diagnosing and discussing dementia is its cultural framing. The phrase demencia en ingles, or “dementia in English,” underscores the need for clear cross-linguistic understanding of medical terminology. Cultural differences influence how symptoms are perceived and whether medical care is sought. In some communities, signs of cognitive decline may be viewed as normal aging or even spiritual phenomena rather than medical issues requiring treatment.

Translating concepts like cognitive impairment into other languages requires more than direct word-for-word substitution. It involves conveying the cognitive, emotional, and social dimensions of the condition in a way that resonates with diverse populations. As global awareness of cognitive health grows, ensuring that terms like what is dementia and what is MCI are accessible across languages is critical to promoting health equity.

Long-Term Cognitive Health: Prevention, Monitoring, and Hope

The increasing prevalence of cognitive disorders has spurred growing interest in how to preserve brain health across the lifespan. Strategies for reducing the risk of dementia include controlling cardiovascular risk factors, maintaining physical activity, following a Mediterranean-style diet, and engaging in lifelong learning. These interventions are particularly impactful during the MCI stage, when the brain retains significant capacity for compensation and repair.

Regular monitoring of cognitive performance, particularly in those with a family history of dementia or known risk factors, can facilitate early diagnosis and intervention. While there is no cure for most forms of dementia, early treatment can slow progression and improve quality of life. Addressing what brings on dementia or accelerates MCI can help clinicians personalize prevention strategies and delay the onset of severe cognitive decline.

Advances in neuroimaging, biomarkers, and digital cognitive testing are opening new frontiers in early detection. These tools may soon make it possible to identify MCI and dementia years before symptoms appear. With earlier recognition, individuals can take proactive steps to preserve function, engage in clinical trials, or plan for future care needs. This proactive approach is a cornerstone of modern cognitive health strategy.

Frequently Asked Questions: Mild Cognitive Impairment vs. Dementia

1. How does mild cognitive impairment affect emotional well-being over time?

Mild cognitive impairment can subtly affect emotional health even before more noticeable cognitive symptoms emerge. Individuals may feel frustration, embarrassment, or anxiety when they forget names, struggle to recall recent conversations, or feel overwhelmed by tasks they once found simple. These feelings can sometimes lead to social withdrawal or even depression, which may further worsen cognitive function. While the emotional toll may not be as visible as the cognitive decline itself, it plays a key role in how individuals manage their condition. Addressing emotional support early in those diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment may improve long-term outcomes and help reduce the likelihood of progression to dementia.

2. Are there differences in how men and women experience cognitive impairment symptoms?

Emerging research suggests there may be gender-based differences in how cognitive impairment symptoms present and progress. For instance, women often experience faster decline after the onset of symptoms, particularly in verbal memory and executive function. Men, however, may show earlier changes in visuospatial skills and may be more prone to underreporting symptoms. These variations also influence how healthcare providers interpret neuropsychological assessments when distinguishing mild cognitive impairment vs dementia. Gender-specific patterns are becoming increasingly relevant in both research and clinical care as we develop more individualized treatment strategies.

3. What role does bilingualism play in cognitive resilience against dementia?

Bilingualism appears to provide a protective buffer against cognitive decline, with studies showing that lifelong bilinguals may develop dementia several years later than monolinguals. This cognitive reserve is thought to be due to the brain’s constant practice in managing two linguistic systems, which strengthens executive control networks. While it does not prevent the dementia brain from undergoing pathological changes, it may delay the functional expression of symptoms. In individuals with mild cognitive impairment, bilingualism may help sustain higher daily functioning despite underlying neurological damage. Thus, cognitive enrichment through multilingual exposure may be a proactive lifestyle factor worth cultivating.

4. How do sleep disturbances contribute to cognitive impairment and dementia risk?

Sleep disruptions, particularly those related to sleep apnea or insomnia, have been strongly linked to cognitive impairment and may accelerate the transition from mild cognitive impairment to dementia. Poor sleep affects the brain’s glymphatic system, which is responsible for clearing beta-amyloid and tau proteins. These proteins are hallmarks of diseases that cause dementia, such as Alzheimer’s. Addressing sleep disorders early may help reduce the risk of cognitive deterioration. This highlights the importance of integrating sleep assessments into evaluations for what is cognitive loss and other early symptoms.

5. Can occupational or environmental exposures increase the risk of developing dementia?

Long-term exposure to neurotoxic substances, such as heavy metals or solvents in certain industrial settings, has been associated with elevated risks for cognitive decline and dementia. These exposures can cause chronic inflammation or oxidative stress in the brain, contributing to neurodegeneration. While not among the most common causes, they provide valuable insights into what brings on dementia beyond the typical genetic and vascular pathways. Individuals in high-risk professions should undergo routine cognitive screening, especially if they experience early signs of mild cognitive. Environmental health history is an increasingly important component in understanding what is MCI disease and its progression.

6. How does early-life education influence late-life cognitive outcomes?

Higher levels of early-life education are consistently associated with a lower risk of dementia and better cognitive performance in aging. Education is believed to enhance neural efficiency and contribute to what researchers call cognitive reserve, a protective mechanism that allows the brain to compensate for damage. This connection offers insight into why some people with considerable brain pathology may still function normally for longer. When assessing cognitive impairment vs dementia, educational background is factored into the interpretation of test results. Investing in education may thus be seen as a long-term public health strategy for reducing the prevalence of mild neurocognitive disorder and related conditions.

7. What is the relationship between cardiovascular health and dementia risk?

Poor cardiovascular health—marked by hypertension, high cholesterol, obesity, and diabetes—significantly increases the risk for both cognitive impairment and dementia. The vascular system directly affects cerebral blood flow, and its impairment can lead to white matter damage, microinfarcts, or even stroke. These changes are often seen in vascular dementia, one of several diseases that cause dementia. Preventing cardiovascular disease can therefore play a major role in minimizing the likelihood of developing either mild cognitive impairment or a more advanced senile disease. Maintaining heart health may be one of the most effective ways to protect brain health.

8. Can advanced brain imaging differentiate between types of cognitive disorders?

Yes, modern imaging techniques such as PET scans and functional MRI can provide detailed views of the dementia brain and detect biomarkers like amyloid plaques or tau tangles. These scans help differentiate between what is MCI in medical terms and more advanced dementia stages by revealing how specific regions of the brain are functioning or deteriorating. They also aid in diagnosing what diseases cause dementia by showing patterns associated with Alzheimer’s, frontotemporal degeneration, or Lewy body pathology. Imaging is particularly helpful when clinical symptoms are ambiguous or when confirming a diagnosis of mild neurocognitive disorder. As imaging technology advances, early detection and more precise classification of cognitive disorders are becoming possible.

9. How do cultural beliefs influence dementia diagnosis and treatment?

Cultural perceptions strongly shape how individuals and communities understand dementia meaning and react to early symptoms. In some cultures, cognitive impairment symptoms may be normalized as part of aging, while in others they may be misattributed to spiritual or social causes. This can delay diagnosis and limit access to appropriate care. Raising awareness of terms like what is dementia and demencia en ingles in multilingual communities helps reduce stigma and improve healthcare outcomes. Culturally sensitive education campaigns are essential for encouraging early intervention and broadening understanding of what is mild cognitive disorder.

10. What steps can caregivers take to better support someone with mild cognitive impairment?

Supporting someone with mild cognitive impairment requires a balance between offering assistance and promoting independence. Caregivers should focus on creating structured routines, offering memory aids, and ensuring the individual remains socially and mentally engaged. It’s also important to attend to physical health, especially conditions like hypertension or diabetes that may exacerbate cognitive decline. Understanding what does MCI stand for in terms of prognosis helps caregivers plan appropriately and recognize when to seek medical advice. Education and support for caregivers are essential as they navigate the transition between MCI and dementia, especially when the line between the two becomes blurred.

Conclusion: Navigating the Path from MCI to Dementia with Knowledge and Compassion

Understanding the distinction between mild cognitive impairment vs dementia is more than a matter of semantics. It represents a pivotal step in the journey toward informed, compassionate care and proactive health planning. By unpacking the nuances of terms such as what is dementia, what is MCI, and what causes cognitive impairment, we begin to appreciate the spectrum of cognitive health and the many factors that influence its trajectory.

While dementia remains a challenging and often irreversible condition, the early recognition of MCI offers hope. It provides a window of opportunity for intervention, education, and empowerment. Whether through lifestyle modifications, medical management, or simply increased awareness, individuals can influence their brain health in meaningful ways. Clarifying the cognitive impairment definition, recognizing early symptoms, and understanding what is MCI in medical terms are all steps toward a more brain-conscious future.

As research continues to evolve, so too will our ability to distinguish, prevent, and manage cognitive disorders. But at its core, navigating the path from cognitive difficulty to cognitive loss requires not only scientific insight but also empathy, patience, and support. By advancing our knowledge of the dementia brain and the early indicators of mild neurocognitive disorder, we can foster a society that values mental vitality as much as physical health. In doing so, we not only address what is mild cognitive but also embrace the broader goal of lifelong cognitive well-being.

Further Reading:

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI)

Dementia and Cognitive Impairment: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Overlooked cases of mild cognitive impairment: Implications to early Alzheimer’s disease