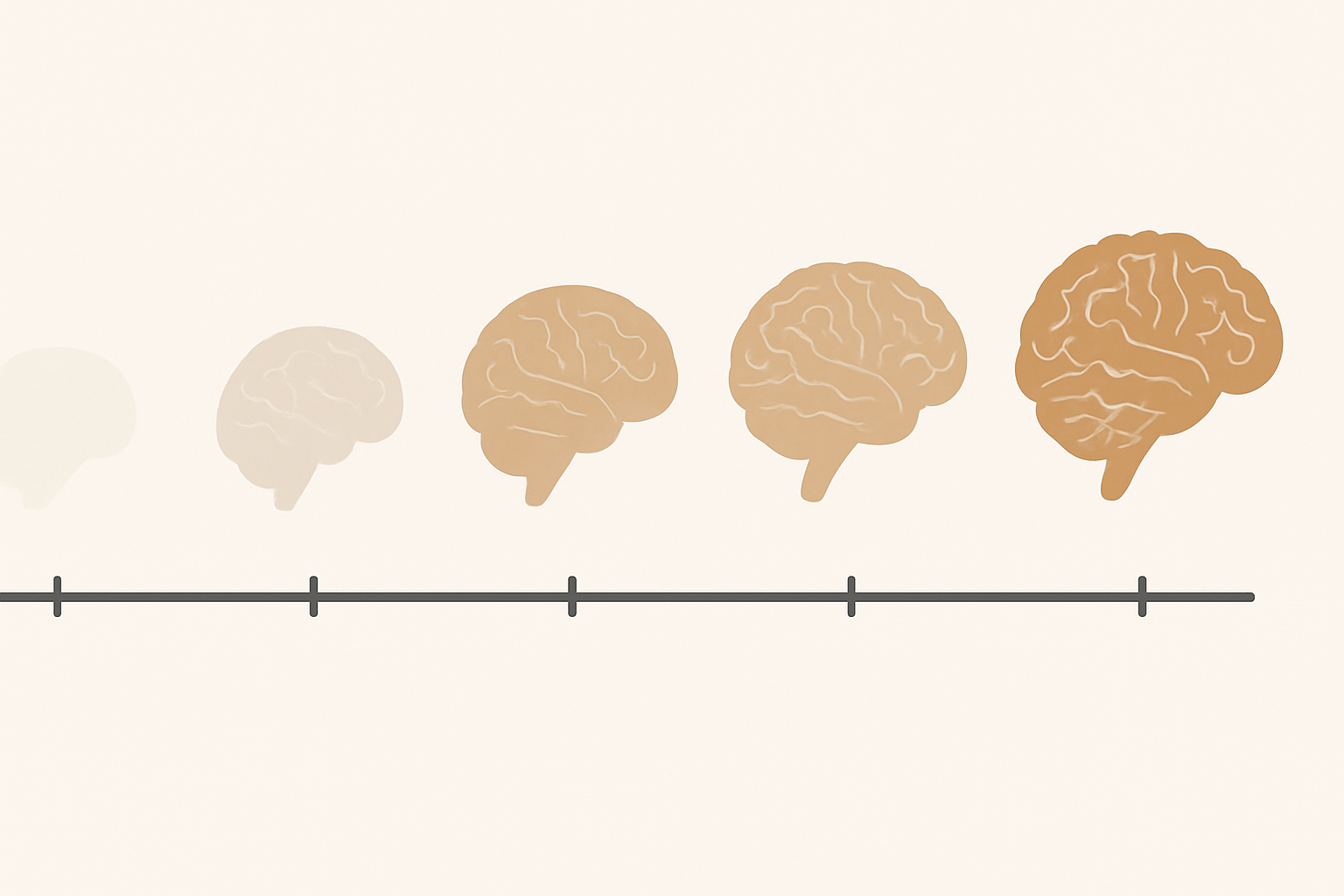

Mild cognitive impairment, often abbreviated as MCI, represents a subtle yet significant decline in cognitive abilities that is more pronounced than typical aging but not severe enough to interfere with daily life in the way dementia does. The mild cognitive impairment timeline has garnered increasing interest among researchers, clinicians, and families due to its nuanced nature and its potential as a precursor to more serious neurodegenerative conditions. Understanding this timeline not only illuminates the early changes in cognition but also empowers individuals and caregivers to recognize when intervention might alter the course of progression. As with many neurological phenomena, the trajectory of MCI is not uniform, and identifying patterns in early symptoms and progression rates has become a central concern for cognitive health professionals.

While many associate cognitive decline with older age, the complexity of MCI extends into younger demographics as well. Increasingly, evidence suggests that subtle markers of cognitive decline in 20s and 30s may be harbingers of more extensive issues later in life, especially when compounded by risk factors such as genetic predisposition, chronic stress, or lifestyle habits. Though often dismissed as mere forgetfulness or distraction, these early symptoms may represent the first deviations along the mild cognitive impairment timeline. Recognizing the distinction between normal aging and pathological decline is essential for timely diagnosis and potential intervention. This nuanced understanding allows for proactive monitoring and lifestyle adjustments that may significantly impact long-term cognitive outcomes.

You may also like: How to Prevent Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease Naturally: Expert-Backed Strategies to Reduce Your Risk Through Lifestyle and Diet

Defining Mild Cognitive Impairment and Its Diagnostic Nuances

To appreciate the full scope of the mild cognitive impairment timeline, one must first understand what MCI entails. Mild cognitive impairment is categorized by a noticeable decline in one or more cognitive domains—such as memory, language, executive function, or visuospatial skills—without the loss of functional independence. Clinicians often differentiate between amnestic mild cognitive impairment and non-amnestic forms, with the former primarily involving memory deficits. The amnestic type, sometimes referred to as amnestic MCI, has been closely linked to the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. In contrast, non-amnestic variants may precede other neurodegenerative disorders or result from vascular changes or psychiatric conditions.

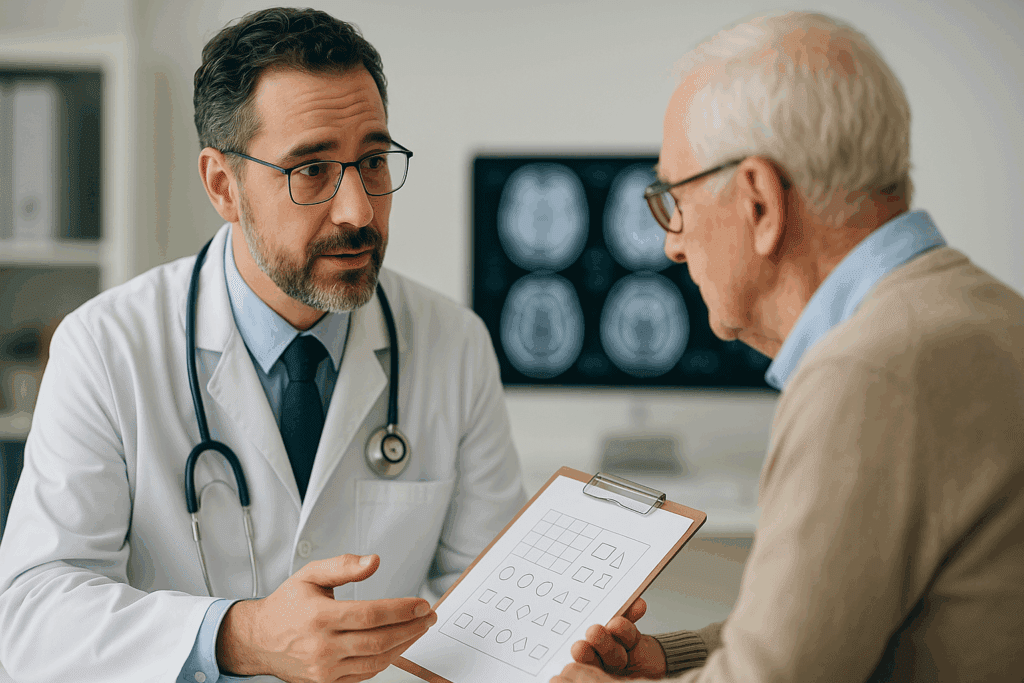

Diagnosis typically involves a combination of clinical assessments, neuropsychological testing, patient history, and sometimes neuroimaging or biomarker analysis. However, MCI remains a diagnosis of exclusion, and it must be distinguished from both normal aging and dementia. This is where the comparison of mild cognitive impairment vs normal aging becomes critical. Normal aging involves occasional lapses in memory or slowed processing speed but does not significantly interfere with complex tasks or problem-solving abilities. In contrast, MCI represents a measurable decline that may raise concern among patients or loved ones, often prompting medical consultation.

Clinicians also assess levels of cognitive impairment using standardized tools such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) or Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), which help quantify deficits and track changes over time. The classification of severity often spans from very mild impairment to moderate MCI, with further gradations informing prognosis and treatment considerations. Importantly, these diagnostic tools are part of a broader clinical narrative that must account for the patient’s baseline functioning, cultural background, and psychosocial context.

Tracing the Onset: What Early Signs Signal the Start of MCI?

One of the most frequently asked questions is: how fast does mild cognitive impairment progress? While the answer varies depending on individual factors, the earliest stages are often characterized by vague, sometimes intermittent symptoms that can be difficult to pinpoint. Subtle memory lapses, such as forgetting recent conversations, missing appointments, or frequently misplacing items, are common initial signs. Individuals with amnestic mild cognitive impairment may notice difficulty in learning new information or recalling names and dates, often attributing these changes to stress or fatigue.

It’s not uncommon for the early symptoms to be overlooked or minimized, especially if the individual is otherwise healthy and functioning independently. However, family members and close colleagues often observe behavioral changes—such as increased reliance on reminders, hesitation in conversation, or difficulty multitasking—that may suggest deeper cognitive shifts. These subtle indicators mark the beginning of the mild cognitive impairment timeline and warrant professional evaluation, especially when they persist or worsen over several months.

The transition from subjective cognitive complaints to objective impairment marks a key diagnostic threshold. This phase often involves a combination of self-awareness and third-party observations, which, together, provide a fuller picture of functional impact. It is also during this period that individuals may begin to experience mild anxiety or frustration due to their cognitive lapses, further complicating the clinical presentation. Such emotional responses, while understandable, can themselves influence cognitive performance, highlighting the importance of comprehensive evaluation.

Understanding the Average Age for Mild Cognitive Impairment

Contrary to popular belief, the average age for mild cognitive impairment does not solely reside in the late elderly years. Although MCI is more commonly diagnosed in individuals over the age of 65, cases in the late 50s and early 60s are increasingly reported. In some cases, even earlier onset is possible, particularly in individuals with a strong familial history of neurodegenerative disease or who have been exposed to cumulative stressors such as traumatic brain injury, chronic sleep deprivation, or unmanaged cardiovascular risk factors.

Emerging research on cognitive decline in 20s raises provocative questions about the long-term trajectory of brain health. While these changes are not typically labeled as MCI at such a young age, longitudinal studies suggest that modifiable risk factors—such as physical inactivity, poor diet, and substance use—may lay the groundwork for accelerated cognitive aging. In this light, the mild cognitive impairment timeline can be reframed not just as a clinical arc occurring later in life but as a continuum shaped by decades of behavioral and environmental influences.

The concept of cognitive reserve—the brain’s resilience to neuropathological damage—also plays a crucial role in determining when symptoms of MCI become clinically apparent. Individuals with higher educational attainment, intellectually stimulating occupations, or rich social networks may manifest symptoms later, even in the presence of underlying pathology. Therefore, while the average age for mild cognitive impairment provides a general benchmark, individual variation is considerable, and a one-size-fits-all model of onset does not suffice.

Amnestic MCI and Its Relationship to Alzheimer’s Disease

Among the various subtypes of mild cognitive impairment, amnestic MCI has received the most attention due to its potential role as a prodromal stage of Alzheimer’s disease. Individuals with the amnestic type often struggle primarily with memory tasks, such as recalling recent events, keeping track of conversations, or remembering planned activities. These memory deficits are more consistent and pronounced than in typical aging and are often the most distressing to both the patient and their family.

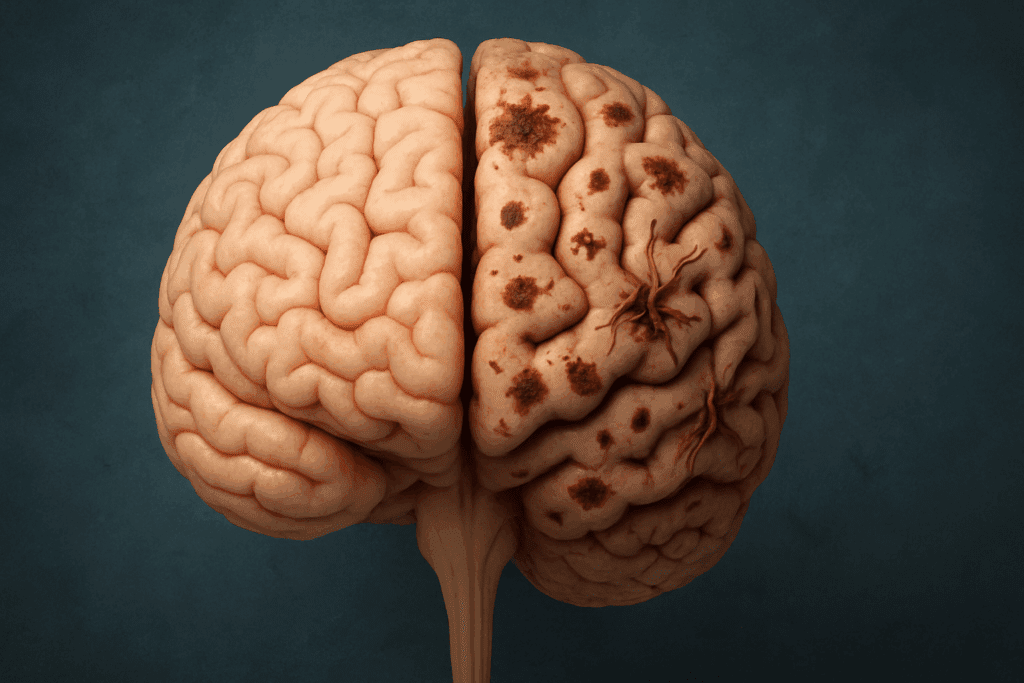

Amnestic mild cognitive impairment is especially concerning because studies have shown that a significant proportion of individuals with this diagnosis progress to Alzheimer’s disease within a few years. Estimates suggest that approximately 10% to 15% of people with amnestic MCI convert to Alzheimer’s annually, though this rate can vary depending on factors such as age, APOE genotype, comorbid conditions, and lifestyle choices. The presence of certain biomarkers—such as beta-amyloid accumulation or tau protein changes on PET imaging—can further refine risk estimates and guide intervention strategies.

The trajectory from amnestic MCI to Alzheimer’s is not inevitable, and this is where the question arises: can cognitive impairment be reversed, or at least slowed? Although no pharmacological cure exists for MCI or early Alzheimer’s, evidence suggests that lifestyle interventions—such as aerobic exercise, cognitive training, and dietary changes—can enhance cognitive reserve and potentially delay progression. Early identification and a proactive, personalized care plan can dramatically alter the course of decline, emphasizing the importance of recognizing the signs of amnestic mild cognitive impairment as early as possible.

Progression Over Time: How Fast Does Mild Cognitive Impairment Progress?

The speed at which MCI progresses varies widely, and understanding this variability is essential for setting realistic expectations. For some, mild cognitive impairment remains stable for years, especially when proactive health measures are taken. Others may see a gradual worsening of symptoms that leads to a formal diagnosis of dementia within three to five years. Multiple longitudinal studies indicate that about 30% of MCI cases revert to normal cognition, while another 30% remain stable and 40% progress to dementia. This variability underscores the complexity of the mild cognitive impairment timeline.

Several factors influence how fast mild cognitive impairment progresses. These include underlying etiology, genetic predisposition, presence of comorbid conditions, and adherence to lifestyle recommendations. For example, individuals with vascular contributions to cognitive impairment—such as hypertension or diabetes—may experience a different progression rate than those with primarily neurodegenerative changes. Similarly, untreated depression or chronic anxiety can exacerbate cognitive symptoms, mimicking or compounding true cognitive decline.

Tracking progression also involves repeated cognitive assessments over time, allowing clinicians to detect subtle shifts in memory, attention, language, or executive function. These changes are often not dramatic but manifest as a slow erosion of mental clarity, organizational ability, or situational awareness. Monitoring these shifts provides invaluable data for tailoring interventions and adjusting expectations, particularly when planning for long-term care or discussing work-related implications.

Can Cognitive Decline Be Reversed or Slowed with Intervention?

The question of reversibility looms large in any discussion of MCI. While the term “reversal” may imply a return to baseline functioning, a more nuanced understanding emphasizes stabilization or functional improvement. So, can cognitive decline be reversed in the context of MCI? In some cases, yes—particularly when the impairment stems from modifiable causes such as medication side effects, nutritional deficiencies, sleep disorders, or untreated mental health issues. Once these factors are addressed, cognitive function can improve significantly.

Even in cases where the decline is due to early neurodegeneration, the progression can often be slowed. Interventions such as Mediterranean-style diets rich in omega-3 fatty acids, regular aerobic and resistance exercise, cognitive engagement, social interaction, and stress management have all demonstrated efficacy in supporting brain health. Emerging therapies also explore the role of neuromodulation, mindfulness practices, and gut-brain axis modulation in mitigating cognitive decline.

Moreover, structured cognitive rehabilitation programs provide tailored exercises designed to enhance specific areas of impairment, such as attention, working memory, or problem-solving skills. These interventions do not cure the underlying pathology but can foster meaningful improvement in daily functioning. Thus, when we ask whether mild cognitive impairment can be reversed, the answer depends on the underlying cause, timing of intervention, and individual responsiveness to treatment.

Mild Cognitive Impairment vs Normal Aging: Knowing the Difference

Differentiating between mild cognitive impairment and normal aging remains one of the most essential yet challenging aspects of cognitive health care. Normal aging involves predictable changes, such as slower processing speed, occasional forgetfulness, or difficulty multitasking. These changes do not interfere with a person’s ability to function independently or maintain meaningful social roles. In contrast, MCI entails a measurable decline in one or more cognitive domains that is greater than expected for age and educational level.

Understanding this distinction is not just academic—it has real implications for when and how people seek help. The difference between mild cognitive impairment vs normal aging lies in the consistency and impact of the symptoms. While normal forgetfulness may be sporadic and context-dependent, MCI-related memory lapses are more frequent and can hinder routine tasks. Individuals with MCI might find it difficult to follow complex conversations, manage finances, or navigate familiar environments, all while retaining a general level of independence.

It is also worth noting that awareness of the impairment is often preserved in MCI, whereas individuals with early dementia may begin to lack insight into their deficits. This preserved self-awareness can be a source of both motivation and distress, making timely support and counseling crucial. For clinicians and families alike, understanding these nuances supports more accurate diagnoses, targeted interventions, and compassionate care planning.

When to Seek Help: Early Recognition as a Catalyst for Intervention

Timely evaluation is a critical turning point in the mild cognitive impairment timeline. While occasional forgetfulness is a common part of life, consistent and noticeable changes in cognition should prompt further assessment. This is particularly true when symptoms begin to affect occupational performance, social relationships, or daily functioning. Seeking help early allows for a comprehensive evaluation that can identify reversible causes, initiate neuroprotective strategies, and provide psychological support.

Family members and caregivers often serve as the first line of observation, noticing changes that the individual may downplay or overlook. Open communication about these concerns, framed with empathy and without alarmism, can facilitate medical consultation without provoking unnecessary fear. Geriatricians, neurologists, and neuropsychologists can provide detailed assessments that differentiate between various levels of cognitive impairment and recommend appropriate follow-up.

An early diagnosis also opens the door to participation in clinical trials or community-based programs aimed at cognitive health promotion. These opportunities can offer access to novel treatments, structured interventions, and valuable support networks. For those navigating the uncertainties of MCI, knowing when and how to seek help transforms uncertainty into proactive care and potentially life-changing clarity.

Frequently Asked Questions: Understanding the Mild Cognitive Impairment Timeline and Related Cognitive Health Concerns

1. What does the mild cognitive impairment timeline reveal about long-term brain health?

The mild cognitive impairment timeline provides valuable insight into how early, mid-stage, and later cognitive changes unfold over time. It can reveal patterns that distinguish temporary mental fatigue from more sustained and concerning declines. While this timeline is often associated with memory-related issues in later life, emerging evidence suggests that cognitive decline can begin subtly in younger decades, including the 30s and 40s. Recognizing these patterns helps clinicians design more individualized monitoring strategies, especially when cognitive decline in 20s is observed alongside family history or lifestyle risk factors. The timeline also informs how fast mild cognitive impairment progresses and helps researchers identify intervention windows when therapies might be most effective.

2. How does the average age for mild cognitive impairment vary across different populations?

The average age for mild cognitive impairment diagnosis in the general population typically hovers around 65 to 70 years. However, certain ethnic and demographic groups may experience onset earlier due to genetic predispositions, socioeconomic disparities, or differential access to healthcare. For example, research suggests that African American and Hispanic populations may encounter symptoms of amnestic MCI earlier, potentially due to higher rates of untreated hypertension and diabetes—both known contributors to vascular cognitive impairment. Differences in educational background and occupational complexity also influence the age of onset, affecting how the brain compensates through cognitive reserve. This suggests that the mild cognitive impairment timeline is not only biological but also socioenvironmental.

3. Is it possible to distinguish cognitive amnestic disorder from normal stress-related forgetfulness?

Cognitive amnestic disorder, particularly when presenting as amnestic mild cognitive impairment, involves a consistent, progressive difficulty with memory that goes beyond occasional forgetfulness. In contrast, stress-induced forgetfulness tends to be temporary and often resolves once the stressor subsides. One useful strategy is to evaluate whether memory lapses are context-dependent—for example, forgetting where you put your keys after a long workday is less concerning than repeatedly forgetting important appointments despite reminders. Another distinguishing factor is whether the issue disrupts daily function over time, a hallmark of amnestic type MCI. Formal neuropsychological assessments help separate these overlapping symptoms and contribute to a more precise understanding of the levels of cognitive impairment involved.

4. What emerging therapies are being studied for slowing the progression of amnestic MCI?

Ongoing clinical trials are exploring a range of innovative approaches to delay progression in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. These include novel anti-amyloid antibodies, neurostimulation techniques such as transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), and gut-brain axis interventions involving probiotics and anti-inflammatory diets. Additionally, personalized cognitive training platforms that adapt in real-time to user performance are gaining traction. These tools are particularly useful in delaying how fast mild cognitive impairment progresses. While no therapy currently offers a cure, the convergence of pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies offers hope for managing amnestic MCI more effectively in its earliest stages.

5. Can cognitive impairment be reversed when detected early, and under what circumstances?

In some scenarios, yes—especially when the cognitive changes are driven by reversible factors like medication side effects, depression, thyroid dysfunction, or nutritional deficiencies. For example, correcting a B12 deficiency or treating obstructive sleep apnea can lead to significant cognitive improvement. In the case of mild cognitive impairment, early lifestyle modifications, cognitive training, and cardiovascular risk management may stabilize or even modestly improve function. Understanding whether a person falls within a reversible category often requires comprehensive testing and monitoring across the mild cognitive impairment timeline. Although not all cases of cognitive decline can be reversed, many can be positively influenced when caught early.

6. How does mild cognitive impairment vs normal aging affect social and professional life differently?

While both MCI and normal aging can involve slower recall or reduced multitasking ability, mild cognitive impairment often begins to interfere with occupational responsibilities or social engagement. For example, someone with amnestic MCI might forget project deadlines or lose track of conversations in meetings, leading to frustration or decreased confidence. Socially, these individuals may withdraw from group settings due to fear of embarrassment over memory lapses. In contrast, normal aging usually involves changes that are manageable with minor adjustments, like using planners or digital reminders. Recognizing the functional impact is key to distinguishing mild cognitive impairment vs normal aging in real-life contexts.

7. Why is cognitive decline in 20s a topic of growing research interest?

Although rare, cognitive decline in 20s has attracted attention due to lifestyle and environmental changes affecting young adults. Chronic stress, excessive screen time, poor sleep hygiene, and substance abuse can all contribute to suboptimal cognitive performance at earlier ages. While such declines don’t typically signal a clinical diagnosis like amnestic MCI, they may indicate risk for earlier onset of MCI later in life. Researchers are now using advanced neuroimaging and biomarker profiling to explore how early these changes can be detected along the mild cognitive impairment timeline. The ultimate goal is to create prevention models that begin decades before traditional symptoms arise.

8. How do clinicians determine the different levels of cognitive impairment during assessment?

Cognitive assessment tools such as the MoCA and MMSE offer baseline scoring for various cognitive domains, but they are only part of the picture. Neuropsychologists also use domain-specific batteries to evaluate memory, attention, executive function, and visuospatial ability in greater detail. Distinctions between normal aging, subjective cognitive decline, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia are drawn based on performance trends, daily functional impact, and trajectory over time. A person with mild decline in one domain may be classified as having early MCI, while those with multi-domain involvement may be approaching dementia. Understanding the levels of cognitive impairment is essential for placing individuals accurately on the mild cognitive impairment timeline and developing a treatment plan.

9. What are the long-term implications of untreated amnestic type MCI?

Untreated amnestic type MCI often results in progressive memory deterioration that can evolve into Alzheimer’s disease within several years. Beyond memory, other cognitive domains such as attention and executive function may also begin to decline, especially as the underlying neurodegenerative process spreads. Social isolation, anxiety, and caregiver burden often intensify as the individual loses autonomy. Without intervention, the question of how fast does mild cognitive impairment progress becomes more urgent, as untreated MCI tends to accelerate over time. Fortunately, proactive monitoring and early therapeutic engagement can significantly slow this trajectory and maintain quality of life for longer periods.

10. Can lifestyle changes truly affect whether cognitive decline can be reversed or stabilized?

Yes, numerous studies have shown that diet, exercise, sleep, and stress reduction can have measurable effects on brain health. For example, adherence to the Mediterranean diet and regular aerobic exercise have been linked to delayed progression in people with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Sleep quality, often overlooked, is especially important because disrupted sleep can accelerate amyloid buildup in the brain. Engaging in cognitively stimulating activities and maintaining strong social networks also buffer against cognitive decline. While lifestyle changes may not completely reverse MCI, they are powerful tools for reshaping the mild cognitive impairment timeline and answering the broader question of whether cognitive decline can be reversed or meaningfully managed.

Conclusion: Empowering Cognitive Wellness Through Early Insight and Action

Understanding the mild cognitive impairment timeline equips individuals, caregivers, and clinicians with the knowledge needed to distinguish early cognitive decline from normal aging, monitor progression with clarity, and intervene before more severe symptoms develop. Whether the issue involves early signs in the 50s, amnestic MCI suggestive of Alzheimer’s risk, or questions about how fast mild cognitive impairment progresses, each point on the timeline presents an opportunity for intervention, hope, and empowerment.

Asking whether cognitive decline in 20s matters, or whether amnestic mild cognitive impairment must always lead to dementia, reframes cognitive health as a lifelong concern rather than a late-life inevitability. The answer to “can cognitive decline be reversed?” is increasingly optimistic when addressed early, with personalized strategies grounded in lifestyle, clinical, and community-based interventions.

The ability to differentiate between mild cognitive impairment vs normal aging is central to this journey. It empowers individuals not just to recognize cognitive change but to meet it with informed, compassionate, and proactive care. In this way, the mild cognitive impairment timeline is not simply a forecast of decline—it becomes a roadmap for resilience, enriched by knowledge, guided by expert insight, and shaped by the meaningful choices we make at every stage of life.

Further Reading:

Mild Cognitive Impairment and Mild Dementia: A Clinical Perspective

Early Detection of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) in Primary Care