Weight loss in dementia is an often overlooked yet critically important aspect of the condition. As dementia progresses, individuals may begin to experience a host of physical changes that extend far beyond the commonly recognized cognitive decline. Among these, unintentional weight loss can significantly impact overall health, quality of life, and even survival outcomes. This article explores the multifaceted nature of losing weight with dementia, including the biological, psychological, and environmental contributors. It also addresses the important question: does dementia cause weight loss, or are other factors equally at play? For caregivers, clinicians, and families, understanding the complexity behind this issue is essential for providing optimal support to those affected by dementia.

You may also like: How to Prevent Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease Naturally: Expert-Backed Strategies to Reduce Your Risk Through Lifestyle and Diet

The Connection Between Dementia and Unintentional Weight Loss

One of the first questions many ask when observing physical changes in a loved one with dementia is whether the weight loss they are witnessing is directly caused by the disease. The answer, while nuanced, lies in the physiological and behavioral effects of dementia. Research has consistently demonstrated that individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia are at a higher risk of unintentional weight loss compared to age-matched peers without cognitive impairment. This suggests that there is indeed a relationship between dementia and weight changes.

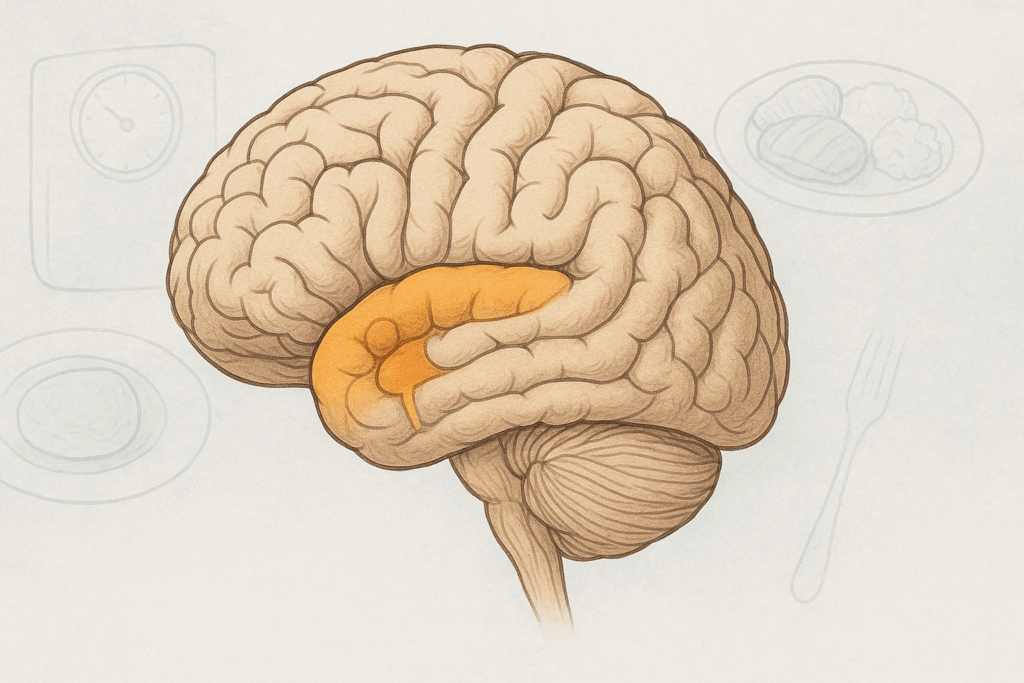

There are several mechanisms through which dementia may lead to weight loss. First, damage to certain areas of the brain can impair appetite regulation, leading to reduced food intake. The hypothalamus, a region responsible for hunger and satiety cues, may no longer function effectively. In addition, changes in taste and smell can make food less appealing, further reducing the desire to eat. People living with dementia may also forget to eat altogether or lose the ability to recognize hunger. These neurological impairments alone can contribute substantially to losing weight with dementia.

Cognitive Decline and Its Influence on Eating Habits

Cognitive deterioration not only alters memory and reasoning but can also have a profound effect on daily routines and nutritional habits. Many individuals with dementia gradually lose the ability to prepare meals or follow multi-step instructions. This means that even if they feel hungry, they might not be able to act on it. In the early stages of dementia, this could manifest as occasional skipped meals or neglected snacks, but as the condition worsens, these lapses can become more frequent and severe.

In later stages, individuals may no longer recognize common foods, utensils, or even the purpose of a meal. They might become agitated or confused during mealtimes, refusing to eat or pushing food away. When such behavioral symptoms persist, the cumulative effect is often significant and unintentional weight loss. This process illustrates how intimately losing weight with dementia is tied to cognitive and functional abilities, not just physiological changes.

Does Dementia Cause Weight Loss Through Psychological and Emotional Changes?

The emotional and psychological toll of dementia is considerable, and its influence on eating habits should not be underestimated. Depression is common among people with dementia and is known to suppress appetite and interest in eating. When a person no longer finds joy or meaning in daily activities, including meals, their nutritional intake often suffers. Social withdrawal can further exacerbate this problem, as shared meals become less frequent and opportunities for stimulation decline.

Anxiety and apathy, both frequent companions of dementia, also interfere with eating behavior. People experiencing anxiety may feel too agitated to sit down for a meal, while those suffering from apathy may simply lack the motivation to eat. The resulting neglect of nutritional needs can subtly but powerfully contribute to weight loss. Thus, when asking, “does dementia cause weight loss,” it becomes clear that emotional states linked to dementia are integral to the answer.

The Role of Physical Changes and Comorbid Conditions

In addition to cognitive and emotional changes, physical factors play a key role in the connection between dementia and weight loss. As dementia progresses, individuals often develop difficulty with chewing and swallowing, a condition known as dysphagia. This can lead to slower eating, aspiration, or even fear of choking, all of which diminish food intake. Furthermore, motor impairments related to advanced dementia may hinder a person’s ability to use utensils or bring food to the mouth.

Medical comorbidities frequently seen in individuals with dementia also contribute to weight loss. Chronic infections, metabolic disorders, gastrointestinal problems, and certain medications can suppress appetite or cause nausea. Polypharmacy, or the use of multiple medications, is particularly prevalent in older adults with dementia and often includes drugs that impair appetite or gastrointestinal function. These overlapping issues underscore the complexity of losing weight with dementia, making comprehensive medical evaluation a critical component of care.

Environmental and Caregiving Factors That Affect Nutritional Status

Beyond internal and biological causes, external factors can significantly influence eating habits and nutritional outcomes in people with dementia. One often overlooked issue is the physical environment in which meals take place. Bright lights, loud noises, or crowded dining spaces can cause sensory overload, leading to agitation or withdrawal during mealtimes. On the other hand, a calming, familiar environment may encourage eating and improve nutritional intake.

Caregiving dynamics also play a critical role. The presence or absence of structured mealtimes, the ability of caregivers to recognize subtle signs of hunger or discomfort, and the provision of appropriate dietary modifications all contribute to whether a person with dementia maintains a healthy weight. Inconsistent care, lack of nutritional knowledge, or emotional burnout among caregivers can exacerbate weight loss, especially in home settings where medical oversight may be limited.

Nutritional Consequences of Weight Loss in Dementia

Unintentional weight loss in dementia is more than a cosmetic issue; it carries serious health consequences. Loss of lean muscle mass, known as sarcopenia, can impair mobility, increase fall risk, and reduce independence. Nutritional deficiencies resulting from inadequate intake of vitamins and minerals can compromise immune function, delay wound healing, and exacerbate cognitive decline. Over time, these physiological changes may contribute to a cascade of adverse health events that significantly reduce life expectancy and quality of life.

Moreover, weight loss is a known predictor of mortality in dementia. Studies have found that individuals who lose more than 5% of their body weight over six months face significantly higher mortality risks than those who maintain a stable weight. This makes early identification and intervention essential, particularly for those at the moderate to severe stages of dementia. Effective monitoring of weight trends and nutritional intake should be a routine part of dementia care.

Practical Strategies for Managing Weight Loss in Dementia

Intervening in weight loss associated with dementia requires a holistic, patient-centered approach. One of the most effective strategies involves tailoring meals to the individual’s preferences, textures, and cognitive capabilities. For instance, providing finger foods may help those with difficulty using utensils, while enhancing flavor and aroma can compensate for diminished taste and smell. Small, frequent meals may be more manageable than large portions.

Encouraging social engagement during meals can also have a meaningful impact. Studies show that individuals eat more and with greater consistency when meals are shared with caregivers or peers. Creating a pleasant, distraction-free dining environment further supports intake. In some cases, nutritional supplements or calorie-dense snacks can help stabilize weight when traditional meals are insufficient.

Importantly, caregivers should be trained to recognize early warning signs of nutritional decline. Monitoring changes in appetite, interest in food, or clothing fit can help catch problems before they escalate. Collaboration with dietitians, speech-language pathologists (for dysphagia), and physicians ensures a multidisciplinary approach that optimizes both safety and nutritional adequacy.

When Medical Intervention Is Necessary

There may come a point when medical interventions are required to address persistent weight loss in dementia. These can include appetite stimulants, although their use remains controversial due to variable effectiveness and potential side effects. For individuals with severe dysphagia, modified diets or even tube feeding may be considered. However, such decisions must be approached with careful ethical consideration, taking into account the individual’s stage of dementia, quality of life, and personal wishes.

Palliative and hospice care frameworks can offer guidance for families facing end-stage dementia and related nutritional decline. In such cases, the focus often shifts from prolonging life to enhancing comfort, which may mean relaxing strict dietary rules and prioritizing enjoyable food experiences. Understanding the nuanced trajectory of losing weight with dementia allows caregivers and clinicians to make informed, compassionate decisions that honor the individual’s dignity and preferences.

Supporting Caregivers in Nutritional Decision-Making

Caring for someone with dementia is a complex, often exhausting journey, and nutritional support is just one of the many challenges caregivers face. Education and emotional support can make a significant difference in outcomes. Empowering caregivers with information about how and why dementia leads to weight loss fosters proactive, confident caregiving. Tools such as weight monitoring charts, meal planning guides, and access to professional support can reduce anxiety and improve consistency in care.

Equally important is the psychological well-being of the caregiver. The emotional toll of watching a loved one decline, especially when they refuse food or exhibit aversion to eating, can lead to feelings of helplessness or guilt. Caregiver burnout is a real and pressing issue. Support groups, respite care, and counseling services can provide essential relief, helping caregivers sustain their roles without compromising their own health.

The Future of Dementia Care and Nutritional Research

As global populations age and the prevalence of dementia continues to rise, the medical community is increasingly turning its attention to the nutritional aspects of cognitive decline. Emerging research is exploring the role of specific nutrients, such as omega-3 fatty acids, B-vitamins, and antioxidants, in mitigating both cognitive and physical deterioration. Additionally, technology-assisted interventions, including smart devices that monitor eating behavior or provide reminders, offer promising avenues for supporting independence in early-stage dementia.

Personalized medicine is another frontier in dementia care, with genetic and metabolic profiling beginning to inform individualized dietary recommendations. While these innovations remain in the early stages, they signal a shift toward more integrative, responsive care models. In the meantime, continued public health education, caregiver support, and policy reforms will be essential to address the widespread issue of losing weight with dementia.

Frequently Asked Questions About Weight Loss and Dementia

1. Can early interventions prevent significant weight loss in people with dementia?

Yes, early interventions can play a critical role in minimizing weight loss in individuals with dementia. While many caregivers first ask, does dementia cause weight loss, it’s important to recognize that early-stage interventions can disrupt that trajectory. Engaging a registered dietitian early in the diagnosis can help customize meal plans that account for shifting cognitive abilities and personal preferences. Regular weight monitoring, sensory-stimulating foods, and structured mealtimes can also delay the onset of nutritional decline. These proactive strategies help reduce the likelihood of losing weight with dementia, improving long-term health outcomes.

2. What role does gut health play in weight changes among dementia patients?

Emerging research suggests that gut health may influence both cognition and metabolism, offering new perspectives on why losing weight with dementia is so common. An imbalance in the gut microbiota has been linked to inflammation and reduced nutrient absorption, both of which may exacerbate weight loss in individuals with cognitive impairment. While more studies are needed, supporting digestive health through probiotics and fiber-rich foods might be a valuable adjunct therapy. Addressing gut health doesn’t negate the question does dementia cause weight loss, but it highlights an often-overlooked contributing factor. Integrating this into a comprehensive care plan could enhance both cognitive and physical resilience.

3. Are there gender differences in how dementia affects body weight?

Yes, gender appears to influence how dementia impacts body composition and nutritional status. Some studies have observed that women with dementia are more susceptible to severe weight loss than men, possibly due to differences in hormonal regulation, baseline muscle mass, and how symptoms manifest behaviorally. This may mean that strategies for addressing losing weight with dementia need to be personalized based on gender. While the overarching question does dementia cause weight loss applies to all, the pathways and responses to intervention may differ. Recognizing these nuances can lead to more targeted and effective care.

4. Can meal timing or circadian rhythm disruptions affect nutritional intake in dementia?

Absolutely. Disruptions in circadian rhythms—common in dementia—can confuse the body’s hunger and fullness cues, making it harder to maintain consistent nutritional intake. Many individuals with dementia experience “sundowning,” a phenomenon where agitation and confusion worsen later in the day, often disrupting evening meals. These erratic patterns can indirectly contribute to losing weight with dementia by making regular eating habits unsustainable. Even though the biological basis of does dementia cause weight loss remains complex, dysregulated meal timing is a contributing factor worth addressing. Structured, earlier meals and light therapy may help stabilize these rhythms.

5. How do cultural food preferences impact weight maintenance in dementia patients?

Cultural familiarity with food can significantly influence appetite in individuals with dementia. As cognition declines, the brain often retains emotional memory longer than factual memory. Serving traditional or culturally significant dishes may trigger positive associations and encourage eating, making it a powerful strategy for preventing losing weight with dementia. While does dementia cause weight loss is a medically relevant concern, the emotional connection to food is a practical way to counteract that trend. Caregivers should consider integrating cultural dishes into mealtime routines to enhance food recognition and engagement.

6. Are there risks associated with using appetite stimulants for weight loss in dementia?

Yes, while appetite stimulants like megestrol acetate or mirtazapine are sometimes prescribed, their benefits must be weighed carefully against potential side effects. These medications can increase appetite temporarily, but they may also carry risks such as fluid retention, sedation, and thromboembolic events. Their use doesn’t directly address the core reasons does dementia cause weight loss, such as neurological and behavioral changes. Furthermore, stimulants do not guarantee improved nutrition if the quality of food intake remains poor. For many, non-pharmacological approaches are safer and more sustainable when managing losing weight with dementia.

7. How can technology assist with monitoring and managing nutrition in dementia care?

Innovative technologies are increasingly being used to support meal tracking, nutritional intake, and early detection of weight changes. Smart scales, app-based food logs, and reminder devices can all assist caregivers in maintaining consistent monitoring. Some tools even use AI to detect behavioral changes that may signal declining appetite. These resources don’t alter the fact that losing weight with dementia is common, but they empower families to respond more promptly. Although they don’t answer does dementia cause weight loss definitively, they help mitigate its progression by alerting caregivers to concerning trends in real time.

8. What are the ethical considerations around feeding interventions in advanced dementia?

In advanced stages, families often face difficult decisions about artificial nutrition, such as feeding tubes. While losing weight with dementia can be distressing, invasive feeding methods don’t always improve survival or quality of life. Ethical frameworks recommend prioritizing comfort and dignity, especially when the act of eating no longer holds meaning for the individual. The question does dementia cause weight loss evolves in this context, shifting from clinical management to quality-of-life considerations. Conversations with palliative care teams can help navigate these choices in a compassionate and individualized way.

9. Could sensory therapies help stimulate appetite in dementia patients?

Yes, sensory-based interventions are gaining attention as non-invasive methods to boost appetite. These include aromatherapy, music therapy during meals, textured tableware, and visual food enhancements. These therapies can create a more engaging and less stressful eating environment, which may counteract the effects of losing weight with dementia. They don’t change the biological underpinnings that prompt the question does dementia cause weight loss, but they can work around them. These approaches align with person-centered care and are particularly effective when tailored to the individual’s preferences and history.

10. How can long-term care facilities better address nutritional decline in residents with dementia?

Many institutional settings struggle to provide individualized mealtime support due to staffing constraints and rigid schedules. However, facilities that implement flexible dining options, staff training in dementia care, and sensory-friendly meal environments often see better outcomes. Losing weight with dementia should not be considered inevitable in these settings if proactive, resident-centered practices are employed. Answering does dementia cause weight loss requires understanding the systemic and structural factors in care environments. Long-term facilities must invest in both policy and practice changes to prevent malnutrition and uphold residents’ dignity.

Final Thoughts on Weight Loss and Dementia: What Families and Clinicians Need to Know

Understanding the intricacies of weight loss in the context of dementia reveals a complex interplay of neurological, emotional, physical, and social factors. It is not sufficient to view weight loss as an isolated symptom or an inevitable part of the disease. Rather, it should be recognized as a meaningful clinical indicator—one that signals the need for timely assessment and intervention.

When asking, “does dementia cause weight loss,” the answer becomes clearer through comprehensive exploration. Dementia can indeed lead to weight loss, but it often does so through a convergence of related impairments, behaviors, and environmental influences. A proactive, compassionate approach—one that includes personalized nutrition plans, caregiver support, medical oversight, and a nurturing environment—can significantly improve outcomes.

For caregivers and families, recognizing the early signs of nutritional decline and responding with empathy and knowledge can help sustain not only the weight and health of the person with dementia but also their dignity, comfort, and joy. With the right support systems in place, it is possible to navigate the challenges of losing weight with dementia in a way that honors both science and humanity.

Further Reading:

Dementia severity and weight loss: A comparison across eight cohorts. The 10/66 study

Weight Loss in Patients with Dementia: Considering the Potential Impact of Pharmacotherapy