Understanding dementia has become increasingly critical as populations age and cognitive health becomes a focal point in both public discourse and healthcare policy. Yet despite its prevalence, confusion still surrounds a fundamental question: Is dementia a mental illness or something else entirely? For those navigating a diagnosis, caring for a loved one, or researching its progression, clarity on this matter holds profound implications for treatment, support, and stigma. From clinical classifications to the lived experience of those affected, the answer is layered and multidimensional.

Dementia encompasses a broad range of cognitive impairments that interfere with daily functioning, and while these symptoms share some overlap with traditional psychiatric disorders, experts increasingly argue that dementia should not be simplistically categorized as a mental illness. At the same time, acknowledging its psychiatric dimensions can help frame appropriate interventions and reduce barriers to care. This article explores the clinical definitions, neurological underpinnings, and psychological components of dementia to uncover whether it is accurate to label dementia a mental disorder or if doing so obscures its true complexity.

You may also like: How to Prevent Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease Naturally: Expert-Backed Strategies to Reduce Your Risk Through Lifestyle and Diet

Defining Dementia Through a Medical Lens

From a strictly medical standpoint, dementia is recognized as a syndrome—a cluster of symptoms that result from damage to the brain caused by various diseases. The most common form is Alzheimer’s disease, but other types include vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, frontotemporal dementia, and mixed dementias. All involve a progressive decline in memory, thinking, behavior, and the ability to perform everyday activities. Despite its wide-ranging symptoms, dementia is not a disease itself but a descriptor of cognitive deterioration resulting from underlying pathology.

This distinction matters. Labeling dementia as a mental illness implies a psychological rather than a neurological cause, which is not medically accurate. Instead, dementia is the result of biological changes in the brain. These include the accumulation of amyloid plaques and tau tangles in Alzheimer’s disease or small vessel damage in vascular dementia. Modern neuroimaging studies and autopsy reports confirm the presence of structural brain changes that distinguish dementia from primary psychiatric conditions.

Still, confusion persists. The overlap in symptoms—such as depression, paranoia, hallucinations, and changes in mood—can blur the line between neurological and psychiatric classifications. This overlap often leads individuals to ask, “Is dementia considered a mental illness?” The answer is nuanced. While dementia is not categorized as a primary mental health disorder like major depressive disorder or schizophrenia, it frequently presents with co-occurring mental health symptoms, complicating both diagnosis and care.

The Role of Psychiatry in Dementia Diagnosis and Treatment

Despite its classification as a neurological condition, dementia is often managed, in part, by mental health professionals. This fact alone can contribute to the perception that dementia is a mental health disorder. Psychiatrists, especially geriatric psychiatrists, play a critical role in diagnosing dementia, managing behavioral symptoms, and addressing mood disturbances that may arise alongside cognitive decline.

The psychiatric interface is particularly evident in the early stages of the disease. Symptoms such as apathy, irritability, anxiety, and emotional instability can closely mimic psychiatric disorders, especially in older adults. These presentations can lead to initial misdiagnoses of depression or anxiety before cognitive testing reveals more profound impairments. The complexity of symptom presentation adds to the ongoing debate about whether dementia is a mental disorder or something distinct.

To further complicate the picture, psychiatric medications are often used to manage behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), including aggression, hallucinations, or sleep disturbances. Antipsychotics, antidepressants, and mood stabilizers are prescribed selectively, albeit cautiously, due to the elevated risk of side effects in this population. The reliance on psychiatric treatment methods reinforces the idea that dementia has a significant psychological component, even if its origins are neurological.

Why Dementia Is Not Categorized as a Mental Illness in Diagnostic Manuals

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), provides a critical distinction in how dementia is classified. It no longer refers to dementia as a standalone term but instead uses “major neurocognitive disorder” to describe its diagnostic criteria. This change reflects a shift toward acknowledging the neurological underpinnings of dementia while maintaining its relevance to mental health care providers.

The DSM-5 outlines major and mild neurocognitive disorders based on cognitive decline in domains such as memory, attention, language, and executive function. It clearly separates these disorders from primary mental illnesses, underscoring the difference in etiology. This distinction answers, to some degree, the question: “Is dementia considered a mental disorder?” Clinically speaking, it is considered a neurocognitive disorder with psychiatric manifestations, but not a mental illness per se.

Similarly, the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), published by the World Health Organization, categorizes dementia within diseases of the nervous system rather than mental and behavioral disorders. These classifications have critical implications for treatment protocols, insurance coverage, and public perception. They help delineate the roles of neurology, psychiatry, and primary care in managing the condition.

The Psychological Impact of Dementia on Patients and Families

Even if dementia is not defined as a mental illness, its psychological toll cannot be overstated. Individuals with dementia often experience profound shifts in identity, emotional regulation, and interpersonal relationships. The awareness of declining mental faculties can lead to depression, frustration, and even suicidal ideation in early stages of the illness. Families, too, suffer emotionally as they witness the cognitive and behavioral transformation of a loved one.

Caregiver burden is a well-documented consequence of dementia, and its psychological implications are far-reaching. Spouses and adult children often take on roles that challenge their emotional resilience, especially when behavioral disturbances escalate. In this context, the mental health aspects of dementia extend beyond the patient to encompass the entire care network. This broader view reinforces the relevance of the term “dementia psychological disorder,” particularly in its capacity to disrupt emotional and relational stability.

Support services often focus on both cognitive and emotional well-being, offering counseling, behavioral interventions, and community support to address the psychological fallout. Whether or not dementia is classified as a mental health disorder, its ripple effects create a landscape that is undeniably psychological in nature.

Stigma and Misconceptions: Why Terminology Matters

One of the most compelling reasons to clarify whether dementia is a mental illness lies in the issue of stigma. Mental illness still carries negative connotations in many cultures, often leading to shame, denial, or delayed medical attention. If dementia is misunderstood as a purely psychiatric disorder, individuals and families may hesitate to seek timely intervention.

On the flip side, categorizing dementia strictly as a neurological disorder may downplay the very real emotional and behavioral symptoms that require psychiatric care. Striking a balance in terminology—one that acknowledges both the neurobiological roots and psychological consequences of the disease—is essential to providing holistic, compassionate care.

Moreover, the use of specific phrases like “is dementia a mental health disorder” or “is dementia a mental illness” in media, educational materials, and healthcare discussions influences public perception. When used without context, these terms can reinforce outdated notions or create confusion. For instance, some may assume that dementia is treatable with talk therapy alone, while others may mistakenly believe it results from personal weakness or poor lifestyle choices.

Education plays a crucial role in dismantling these myths. Accurate, accessible information about dementia’s complex nature can foster empathy, reduce fear, and encourage proactive health behaviors. Public campaigns that clarify the distinction between mental illness and cognitive impairment can also help align expectations and improve outcomes.

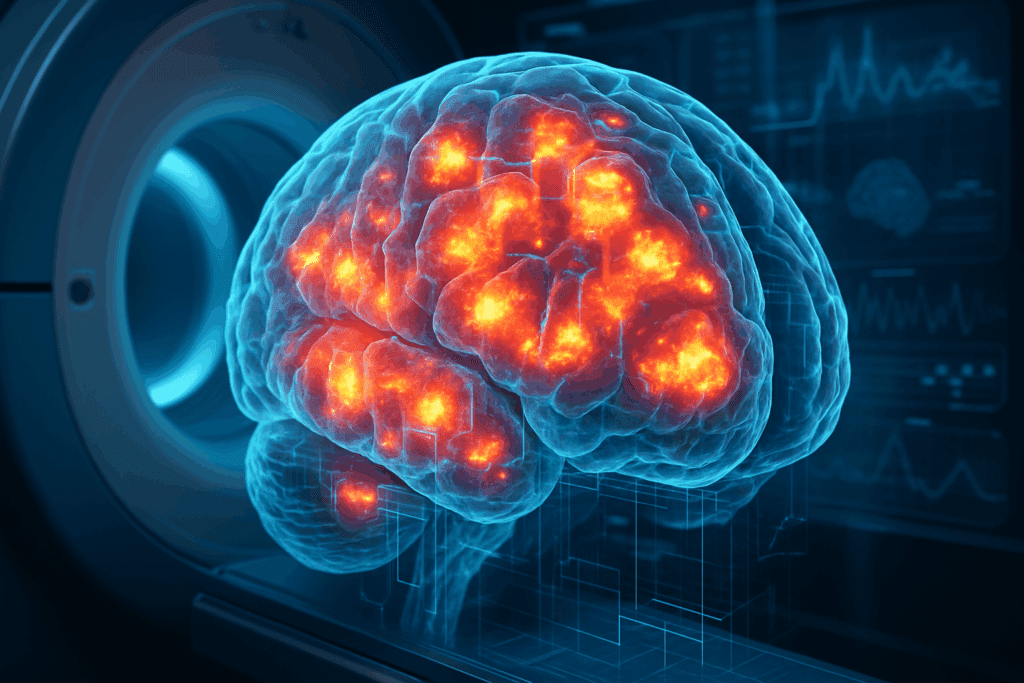

Dementia’s Neurological Footprint and How It Shapes Clinical Understanding

Advances in neuroscience have further reinforced dementia’s classification as a brain-based disorder. Functional MRI (fMRI), positron emission tomography (PET), and other imaging technologies allow clinicians to observe changes in brain metabolism, synaptic density, and structural integrity long before clinical symptoms emerge. These insights provide a biological map of cognitive decline that is markedly different from the brain profiles seen in primary psychiatric disorders.

For instance, Alzheimer’s disease is associated with specific patterns of cortical atrophy, particularly in the hippocampus and temporal lobes—regions critical for memory formation and retrieval. Vascular dementia shows evidence of white matter lesions and infarcts, while Lewy body dementia is characterized by the presence of abnormal protein deposits that interfere with neurotransmission. These pathological signatures offer a clear distinction between dementia and classic psychiatric conditions such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia.

Still, the waters remain murky when psychiatric symptoms emerge as part of dementia’s trajectory. Hallucinations in Lewy body dementia, for example, may mimic those seen in schizophrenia, leading to initial diagnostic confusion. In such cases, even experienced clinicians must rely on longitudinal assessment, collateral history, and neuroimaging to make an accurate diagnosis.

Integrative Care Models: Bridging Neurology and Psychiatry

Because dementia straddles the line between brain disease and psychological disorder, an integrative approach to care offers the most promise. Multidisciplinary teams that include neurologists, psychiatrists, neuropsychologists, and geriatricians can tailor interventions to address both the cognitive and emotional facets of the illness.

This holistic model is particularly effective in managing comorbid conditions. For example, many individuals with dementia develop depressive symptoms, which can exacerbate cognitive decline if left untreated. Simultaneously treating mood disorders and cognitive symptoms requires careful coordination between specialties. Behavioral interventions, cognitive stimulation therapy, and psychosocial support are increasingly integrated into care plans alongside medication management.

Furthermore, such models acknowledge that dementia is not solely the domain of neurology. Psychiatric expertise is invaluable in recognizing and managing behavioral challenges, reducing caregiver distress, and enhancing quality of life. By recognizing that dementia has both neurological and psychological dimensions, healthcare providers can offer more nuanced and comprehensive support.

Reframing the Question: Is Dementia a Mental Illness or Something Else?

So where does this leave us? Is dementia a mental illness, or is it something entirely different? The most accurate answer may be that dementia is a neurocognitive disorder with significant mental health implications. It is not a mental illness in the traditional sense, as it originates from structural and chemical changes in the brain. However, its manifestations often mirror those seen in psychiatric conditions, and it frequently requires psychological and behavioral interventions.

From a clinical perspective, understanding that dementia is not simply a mental disorder helps refine diagnosis, guide appropriate treatment, and reduce stigma. From a caregiving and public health standpoint, recognizing its psychological impact ensures that emotional needs are not neglected. The most effective responses to dementia occur when its dual nature—neurological and psychological—is fully acknowledged.

Ultimately, the question “is dementia considered a mental disorder” should be less about drawing hard boundaries and more about encouraging integrative care and informed awareness. By embracing a hybrid model that includes both brain and mind, society can move toward a more compassionate, evidence-based approach to dementia care.

Frequently Asked Questions: Understanding Dementia as a Mental and Neurological Condition

1. Can dementia symptoms be mistaken for other mental health disorders in early stages?

Yes, early-stage dementia is often misdiagnosed as depression, anxiety, or even late-onset schizophrenia. This misidentification stems from overlapping symptoms such as mood changes, confusion, irritability, and withdrawal from social interactions. Since the question “is dementia a mental illness” continues to generate debate, these early psychiatric-like signs can cause clinicians to initially overlook cognitive decline. However, comprehensive neuropsychological testing and long-term observation usually reveal dementia’s progressive nature, which differs markedly from episodic psychiatric conditions. Recognizing this pattern early can prevent unnecessary treatment delays and ensure more accurate intervention pathways.

2. How does the classification of dementia influence patient care and insurance coverage?

Understanding whether dementia is a mental disorder or a neurocognitive condition has direct implications for health insurance and care access. When dementia is classified strictly as a neurological disease, mental health services may be underutilized despite their necessity in addressing behavioral symptoms. Conversely, if it’s viewed primarily as a mental illness, neurologically driven treatments might be inadequately covered. This classification gap can lead to fragmented care. As public awareness of dementia psychological disorder increases, some healthcare systems are now working toward integrated models that bridge the gap between neurological and psychiatric coverage, offering patients more cohesive treatment.

3. What role does environment play in managing psychological symptoms of dementia?

Environmental factors can significantly affect whether symptoms of dementia manifest more as behavioral disturbances or psychological distress. Patients in overstimulating or unfamiliar settings often exhibit increased agitation, delusions, or fear. These changes reinforce the relevance of the term “is dementia a mental health disorder,” as the surroundings directly impact mental well-being. Care strategies that prioritize routine, calming stimuli, and familiar faces can reduce these symptoms. Thus, modifying the care environment can act as a non-pharmacological therapeutic approach that mitigates both cognitive and emotional challenges.

4. Could a dementia diagnosis increase a person’s risk for developing clinical depression?

Yes, the emotional toll of receiving a dementia diagnosis, especially in the early stages when awareness remains high, can significantly raise the risk of clinical depression. Unlike some psychiatric disorders that emerge without a clear triggering event, this form of depression is situational and often a response to perceived loss of identity, autonomy, or future purpose. While dementia is not universally considered a mental illness, its psychological consequences can be severe and require dedicated mental health care. Treating this secondary depression involves both pharmacologic and counseling interventions tailored to the cognitive capacity of the patient.

5. How do cultural views shape public perceptions of dementia as a mental illness?

Cultural attitudes heavily influence whether people believe dementia is a mental illness or a natural part of aging. In some communities, cognitive decline is seen as a spiritual issue or moral failing rather than a medical condition. This belief system may prevent early diagnosis or discourage families from seeking professional help. When dementia is perceived as a mental disorder, it may carry additional stigma, especially in societies where psychiatric illness is taboo. Increasing culturally sensitive education and destigmatization campaigns can help bridge this knowledge gap and promote more compassionate care for those affected.

6. Are caregivers psychologically affected by the mental disorder aspects of dementia?

Absolutely. Caregivers often experience emotional exhaustion, anxiety, and even post-traumatic stress related to managing the unpredictable behaviors associated with dementia psychological disorder. Unlike purely neurological symptoms like memory loss, behavioral symptoms—such as aggression or paranoia—can feel personally targeted, leading to caregiver guilt or resentment. The debate around “is dementia considered a mental illness” extends to these emotional ripple effects, which suggest that supporting caregivers should be an integral part of any treatment plan. Programs offering respite care, counseling, and education significantly improve caregiver resilience and long-term patient outcomes.

7. Do treatments differ when dementia presents primarily as a psychological disorder?

When dementia’s symptoms manifest predominantly as psychiatric in nature—such as delusions, hallucinations, or extreme mood swings—treatment plans may prioritize mental health interventions over standard cognitive therapies. Although the root cause remains neurodegenerative, these presentations challenge traditional treatment hierarchies and push clinicians to ask: “Is dementia considered a mental disorder in this context?” Antipsychotic medications, mood stabilizers, and behavior modification strategies may take precedence, especially in cases of Lewy body or frontotemporal dementia. Personalized care, often guided by psychiatric expertise, ensures these patients receive support aligned with their dominant symptom profile.

8. What future technologies could reshape how we view dementia and mental illness?

Emerging technologies like digital phenotyping, AI-driven diagnostics, and neuro-biomarker mapping are rapidly evolving how clinicians understand and categorize dementia. These innovations may eventually differentiate subtypes based on psychological versus cognitive symptomatology, reigniting the debate over whether dementia is a mental illness or a broader spectrum disorder. Wearable devices that track mood changes, sleep patterns, and speech cadence can offer predictive insights into both mental disorder progression and neurological deterioration. Such advancements could lead to more precise, targeted therapies and reduce the reliance on subjective clinical evaluations.

9. Why do some legal systems still treat dementia as a mental illness?

In legal and forensic contexts, dementia is often treated as a mental disorder, especially in matters involving competency, guardianship, or criminal responsibility. This classification reflects the law’s reliance on older psychiatric frameworks that equate diminished cognition with mental incapacity. The question “is dementia a mental illness” becomes particularly relevant when courts must determine an individual’s ability to make decisions or stand trial. Although newer medical definitions emphasize neurodegeneration, legal systems may lag behind in adopting these distinctions. Advocacy for evidence-based legal reform is growing, aiming to align jurisprudence with contemporary medical understanding.

10. Can classifying dementia as a mental health disorder improve access to therapy and emotional support?

Interestingly, viewing dementia through the lens of a mental health disorder can, in some cases, expand access to beneficial therapies like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness-based interventions, and structured support groups. While not all mental health strategies are suitable for every dementia stage, early diagnosis offers a window for meaningful engagement. Although it may not be entirely accurate to say that dementia is a mental illness, this classification opens doors within certain healthcare systems for reimbursement, specialist referrals, and integrated care. Therefore, balancing the neurologic and psychiatric dimensions can ultimately enhance the therapeutic landscape for individuals and families alike.

Conclusion: Understanding the Nature of Dementia as a Neurocognitive and Psychological Disorder

In answering the question “Is dementia a mental illness or something else?” we are compelled to consider the biological, psychological, and social dimensions of this complex condition. While dementia is primarily a neurological disorder, its behavioral and emotional manifestations often require psychiatric intervention. Clinically, it is more accurately described as a major neurocognitive disorder rather than a traditional mental illness. However, its overlap with psychiatric symptoms—and the need for mental health support—makes it uniquely positioned at the intersection of neurology and psychology.

The importance of this distinction cannot be overstated. Mislabeling dementia as a purely mental illness risks minimizing the organic brain changes that define its progression. At the same time, ignoring its psychological consequences can lead to inadequate care and increased suffering for patients and caregivers alike. By understanding dementia as both a neurological and psychological disorder, healthcare providers and the general public can better navigate its challenges and implement more holistic, effective interventions.

In conclusion, rather than asking solely “is dementia a mental health disorder” or “is dementia considered a mental illness,” we might better serve those affected by the disease by reframing the discussion entirely. Dementia is not just a brain disease and not merely a psychiatric condition—it is a multidimensional health issue that demands equally multidimensional solutions. Through this lens, the path forward becomes clearer, guided by science, empathy, and a commitment to the well-being of both mind and brain.