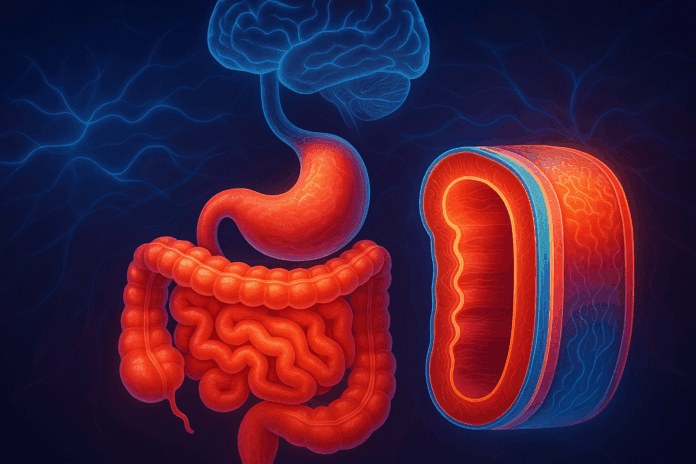

The digestive system, often romanticized as the body’s second brain, does far more than just process food. At its core lies an elegant, multilayered structure that not only drives nutrient absorption and metabolic efficiency but also plays a surprising role in mental well-being. Understanding the intricate architecture of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, including each of the distinct layers of the digestive system, opens a gateway to decoding how disruptions in gut physiology can ripple outward to influence psychological health. In recent years, a surge in research connecting the gut-brain axis to various psychiatric conditions has renewed scientific interest in gut structure, composition, and functionality. This article dives deep into the layers of gut anatomy and physiology, examining how their integrity shapes both gastrointestinal and mental health outcomes.

You may also like: How Gut Health Affects Mental Health: Exploring the Gut-Brain Connection Behind Anxiety, Mood, and Depression

A Closer Look at the Layers of the Digestive System

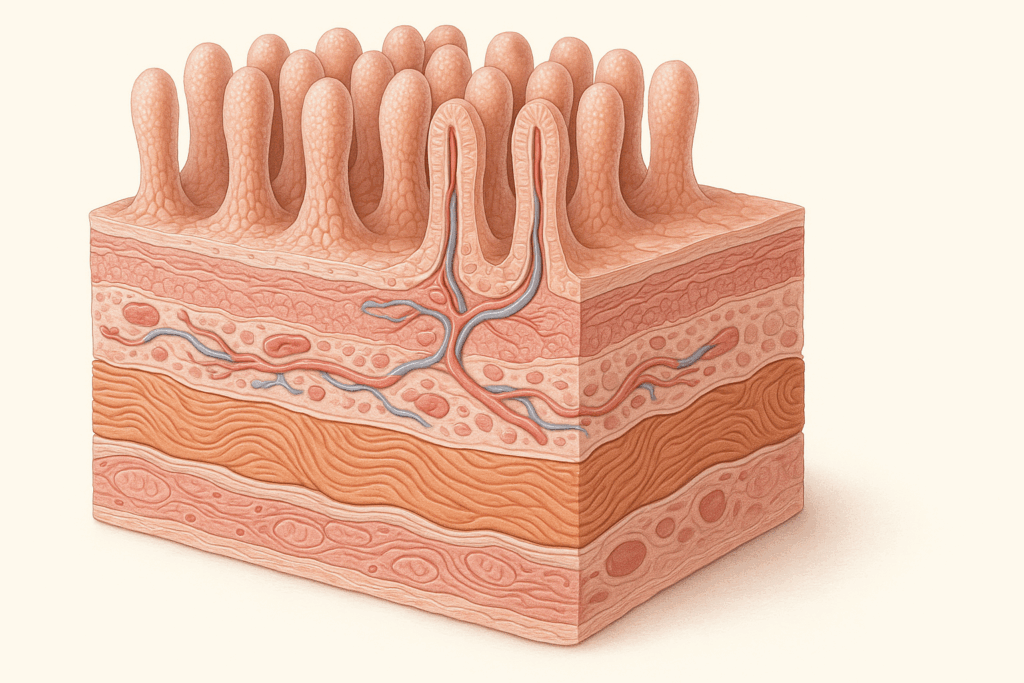

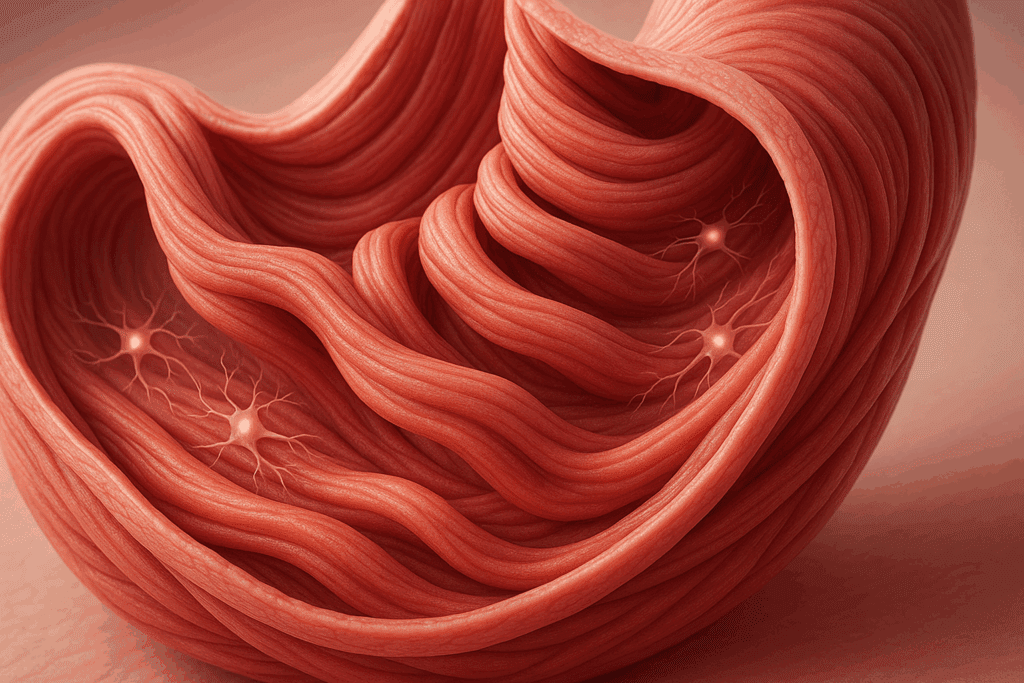

To appreciate how the digestive system contributes to whole-body health, it is essential to understand its anatomical foundation. The layers of the digestive system form a coordinated, protective, and dynamic interface that mediates digestion, immunity, microbial balance, and neurochemical signaling. Classically, the GI tract is organized into four main layers: the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis externa, and serosa (or adventitia, depending on the segment).

The innermost mucosa consists of an epithelial lining responsible for secretion and absorption. It houses specialized cells that release digestive enzymes, mucus, and hormones essential for processing food and communicating with the nervous system. The submucosa, lying beneath, provides structural support and hosts blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerve plexuses. Next comes the muscularis externa, which includes two (sometimes three) layers of smooth muscle responsible for peristalsis. The outermost serosa encloses the organs and acts as a friction-reducing layer.

While the architecture may appear static in diagrams, each of these layers is highly responsive and metabolically active. Together, they form not just a physical barrier but a physiological symphony that shapes the internal environment of the gut. Disruptions in any of these layers can compromise gut function and, through the gut-brain axis, influence mental health. Understanding the layout and purpose of these layers helps decode a wide spectrum of health phenomena.

The Mucosal Layer: First Line of Defense and Communication

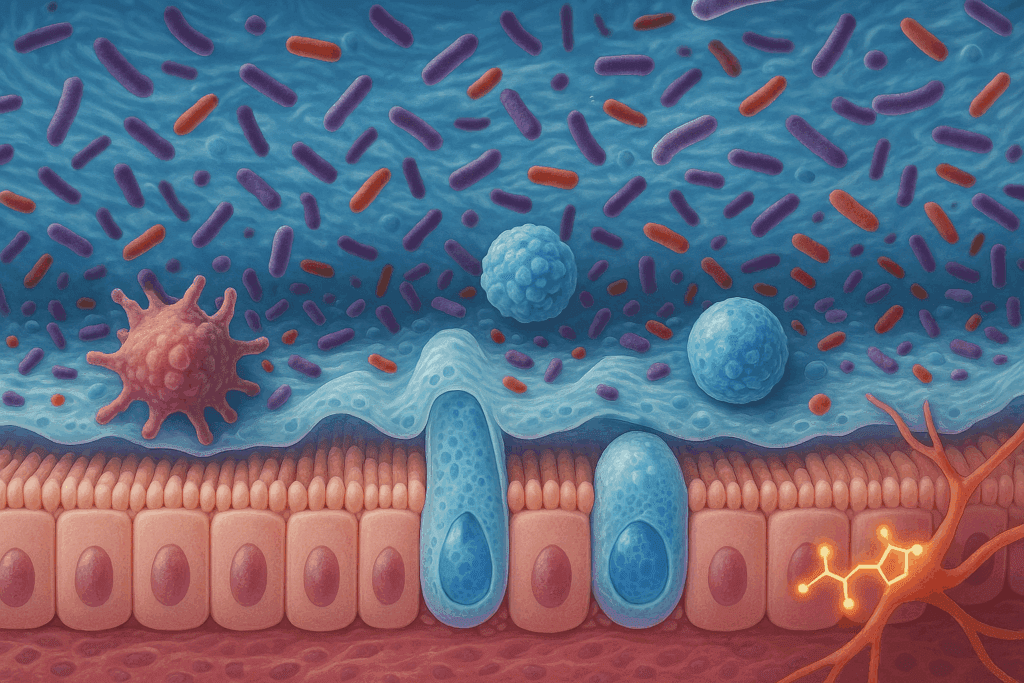

The mucosa serves as the front line where the internal body meets the external environment through ingested food, pathogens, and microbes. It contains a dense population of enterocytes, goblet cells, and enteroendocrine cells. These cells produce secretions that neutralize stomach acid, digest nutrients, and regulate local immune responses. But beyond basic digestion, the mucosa is home to 70-80% of the body’s immune cells, making it the largest immune organ.

Moreover, this layer forms the primary interaction site with the gut microbiota. The microbial metabolites generated in the mucosal space influence the release of neurotransmitters such as serotonin and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), both of which are critical for mental health. Disruption of this layer—whether through inflammation, infection, or poor diet—can lead to increased gut permeability, commonly referred to as “leaky gut.” This breakdown permits toxins and antigens to enter circulation, triggering systemic inflammation that can extend to the brain and contribute to anxiety or depressive disorders.

The mucosa’s role extends into direct neurological signaling. Enteroendocrine cells in the mucosa communicate with the enteric nervous system (ENS) and vagus nerve, sending messages from the gut to the brain in real time. Hence, any dysfunction in this layer can have immediate consequences for both digestive and psychological health.

The Submucosa: Infrastructure for Signaling and Transport

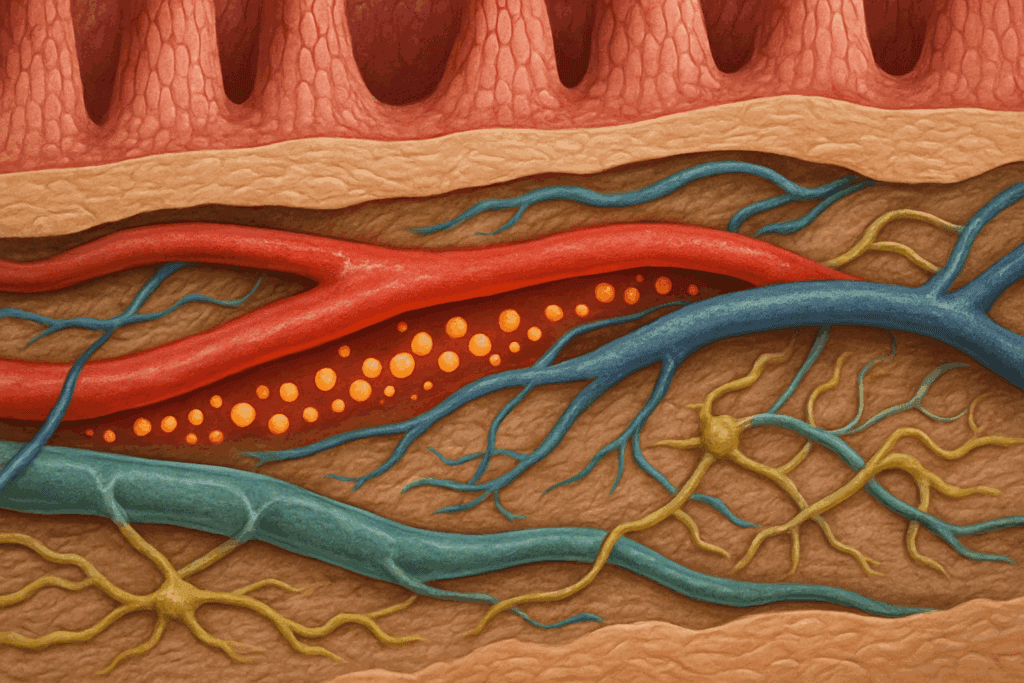

Beneath the mucosa lies the submucosa, a richly vascularized layer that supplies nutrients to the upper tissues while serving as a conduit for neuronal communication. This layer contains the submucosal plexus—a critical component of the enteric nervous system—which governs local blood flow, glandular secretion, and immune surveillance.

The submucosa also facilitates the rapid movement of absorbed nutrients into systemic circulation. Any compromise in this layer can hinder nutrient delivery, which in turn affects neurotransmitter synthesis in the brain. For example, deficiencies in tryptophan, magnesium, or B-vitamins due to malabsorption can impair the production of serotonin and dopamine, leading to mood disturbances. The integrity of this layer, therefore, has indirect but significant implications for cognitive and emotional resilience.

Additionally, the submucosa acts as a buffer zone that prevents mechanical and microbial damage from reaching deeper tissues. Chronic inflammation or microbial dysbiosis can induce fibrotic changes in this layer, reducing its capacity to maintain homeostasis and further compounding psychological distress. Understanding the supportive and integrative role of the submucosa underscores why therapies aimed at healing the gut often focus on this region.

The Muscularis Externa and the Wall of the Stomach Muscle Tissue Type

The muscularis externa is a robust layer composed primarily of smooth muscle, arranged in longitudinal and circular fibers. In the stomach, an additional oblique layer adds to its churning power. This specific wall of the stomach muscle tissue type enables the mechanical breakdown of food and facilitates its propulsion through the digestive tract. These coordinated contractions, known as peristalsis, are essential not only for digestion but also for signaling satiety and timing gastric emptying.

Any dysfunction in this layer—such as impaired motility or delayed gastric emptying—can result in symptoms like bloating, nausea, or constipation, which are frequently co-morbid with mood disorders. Emerging studies suggest that altered motility patterns may contribute to the development of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a condition closely linked to anxiety and depression. The bidirectional relationship between the muscularis externa and mental health illustrates the importance of maintaining the structural and functional integrity of this layer.

Furthermore, the enteric neurons embedded within this layer are influenced by both the central and autonomic nervous systems. Psychological stress can modify their signaling patterns, leading to changes in muscle tone and motility. These findings provide a mechanistic explanation for why emotional distress often manifests as gastrointestinal symptoms and why gut-focused interventions like biofeedback or vagus nerve stimulation can yield psychological benefits.

The Serosa: Barrier and Lubricator in Digestive System Problems

The outermost layer, the serosa, may appear passive, but it plays a crucial role in maintaining the mobility and insulation of the digestive organs. The serosa is a smooth, membranous layer that secretes serous fluid, allowing organs to glide against each other with minimal friction. Although often overshadowed in discussions of gut health, the serosa function in digestive system problems is increasingly recognized.

When the serosa becomes inflamed or fibrotic—conditions seen in diseases like peritonitis or Crohn’s—it can lead to adhesion formation and impaired motility. In such cases, patients may experience both mechanical pain and secondary psychological effects such as chronic anxiety or fatigue due to the body’s stress response. The serosa also acts as a protective barrier against the spread of infection and inflammation to the abdominal cavity, making it a critical player in immune containment.

Recent research also suggests that the serosa interacts with the lymphatic system to regulate immune signaling. Any compromise in this layer could allow for the unchecked dissemination of pro-inflammatory cytokines, potentially exacerbating systemic and neuroinflammatory processes. While much of the literature focuses on more internal layers, the outer casing provided by the serosa is indispensable in preserving the holistic function of the GI tract.

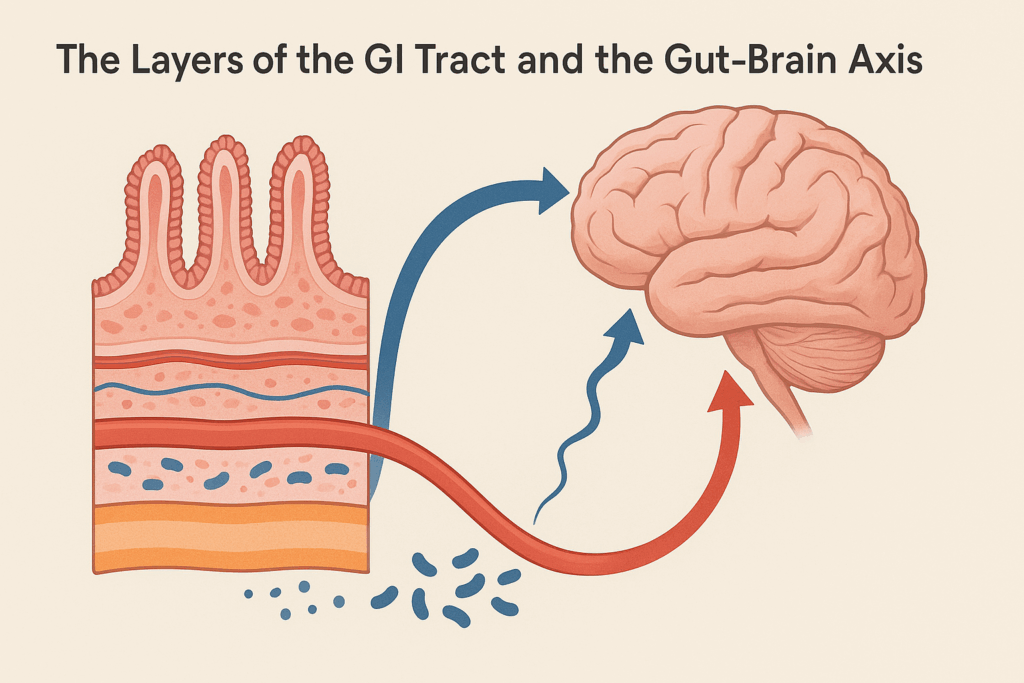

The Layers of the GI Tract and the Gut-Brain Axis

Each of the four layers of the digestive system contributes to the intricate communication network known as the gut-brain axis. This bidirectional system involves neural, hormonal, and immune pathways that connect the GI tract to the central nervous system. The layers of the GI tract are not isolated components but interconnected tissues that collectively influence neurochemical balance, stress response, and emotional regulation.

For instance, the mucosa interfaces directly with gut microbes, whose metabolic products can cross the epithelial barrier and influence brain function. Meanwhile, the muscularis externa coordinates with the vagus nerve to modulate parasympathetic responses. The submucosa facilitates nutrient absorption essential for neurotransmitter synthesis, and the serosa maintains structural integrity under stress. Collectively, these layers shape the internal environment of the gut in ways that resonate throughout the body, including the mind.

Disruptions in any of these layers—whether through injury, infection, chronic inflammation, or stress—can create a cascade of dysfunction that ultimately impacts mental health. This highlights the importance of an integrative medical approach that considers both structural and functional aspects of the gut in treating psychological disorders. The interplay between these layers and the brain represents a new frontier in psychosomatic medicine and underscores the need for interdisciplinary care.

Healing the Gut to Support Mental Health

Recognizing the importance of each gut layer opens up new possibilities for targeted interventions. Healing the mucosa may involve increasing dietary intake of glutamine, zinc, and polyphenols, which support epithelial regeneration. Probiotic therapy can help restore microbial balance, reducing mucosal inflammation and improving neurotransmitter synthesis. For the submucosa, enhancing circulation through moderate exercise and stress management can optimize nutrient transport and immune signaling.

The muscularis externa benefits from therapies aimed at restoring motility, including biofeedback, low-FODMAP diets, and neuromodulation. Ensuring adequate magnesium and potassium intake can also support muscle contraction and prevent spasms. As for the serosa, reducing systemic inflammation through omega-3 fatty acids, anti-inflammatory diets, and mindful stress reduction may help preserve its protective function.

Functional medicine, integrative gastroenterology, and psychoneuroimmunology all offer frameworks for understanding and addressing the structural and biochemical imbalances in the gut that influence mental health. Personalized care that targets specific disruptions within the layers of the digestive system holds the promise of more effective and sustainable treatment outcomes for conditions that span both the body and the mind.

Why the Layers of Gut Matter More Than Ever

In an age where chronic inflammation, stress, and poor nutrition are rampant, the need to understand the layers of gut anatomy and function has never been more pressing. These layers are not merely academic details—they are active participants in shaping human physiology, immunity, and psychological resilience. The increasing prevalence of conditions like IBS, depression, and autoimmune disorders makes it critical to explore how gut integrity underlies both digestive and emotional stability.

Health professionals and researchers are beginning to recognize the layers GI tract function as a central matrix for health. Advanced imaging, biomarker profiling, and neurogastroenterological techniques are shedding light on the nuanced interactions between these layers and the rest of the body. A systems-based understanding that encompasses the wall of the stomach muscle tissue type, the role of the serosa in digestive system problems, and the dynamic interface of the mucosa can revolutionize the prevention and treatment of multifaceted disorders.

Moreover, this knowledge empowers individuals to take proactive steps in supporting their gut health through informed lifestyle choices. From the foods we eat to how we manage stress, every decision influences the micro-architecture of the gut and, by extension, our mental state. The era of siloed medicine is gradually giving way to an integrative vision where the gut is seen not just as a digestive organ but as a foundational platform for holistic well-being.

Rebuilding Gut Integrity for Psychological Resilience

Emerging therapies in regenerative medicine, microbiome modulation, and bioelectronic medicine are offering new tools to repair and enhance the structural and functional integrity of the GI tract. Fecal microbiota transplantation, stem cell therapy, and vagus nerve stimulation are examples of next-generation interventions that target specific layers of the digestive system. These innovations hold promise for patients with treatment-resistant mental health disorders that have gut-based origins.

Nutritional psychiatry also places a strong emphasis on supporting gut structure. Diets rich in prebiotics, fermented foods, and anti-inflammatory nutrients can fortify the mucosa and support microbial diversity. Mind-body therapies such as meditation and yoga can downregulate stress pathways that compromise the muscularis and submucosal layers. The integration of these strategies into standard psychiatric care is an exciting development with the potential to transform treatment outcomes.

Critically, future research must continue to dissect how each layer of the GI tract contributes to mental health outcomes. Longitudinal studies that combine brain imaging, microbiome analysis, and tissue-level diagnostics are needed to validate the mechanisms behind these connections. By grounding clinical practice in a detailed understanding of gut anatomy, healthcare providers can move beyond symptom suppression toward true root-cause resolution.

Frequently Asked Questions: The Layers of the Digestive System and Their Impact on Gut and Mental Health

1. How do different layers of gut tissue respond to long-term psychological stress?

Chronic stress affects the layers of gut tissue in distinct ways. The mucosal barrier may become compromised due to cortisol-induced immune suppression, increasing the risk of gut permeability. Meanwhile, prolonged activation of the sympathetic nervous system can impair blood flow to the submucosa, limiting nutrient exchange and slowing repair processes. The muscularis externa, especially the wall of the stomach muscle tissue type, may develop dysregulated motility patterns, leading to disorders like functional dyspepsia or IBS. Each of these changes across the layers of the digestive system can create a feedback loop, intensifying psychological symptoms through gut-brain axis disruption.

2. Can targeted therapies improve the structural integrity of the layers GI tract over time?

Yes, emerging regenerative therapies aim to repair and strengthen specific layers of the digestive system. For example, the mucosa can benefit from glutamine supplementation and short-chain fatty acid production via fiber-rich diets. The muscularis externa may respond to interventions like electrical stimulation or neuromuscular retraining, particularly where the wall of the stomach muscle tissue type has weakened. The submucosa, when supported by micronutrient therapy, can recover from inflammation-related fibrosis. These personalized strategies reflect a shift toward rehabilitating each layer of gut tissue to restore optimal digestive and mental health.

3. What role does the serosa play in surgical recovery or post-operative digestive complications?

The serosa function in digestive system problems becomes especially critical during and after abdominal surgery. As the outermost layer, the serosa is vulnerable to injury during surgical manipulation, and when damaged, it may contribute to adhesions that impair gut motility. These adhesions can interfere with the natural gliding motion between organs, often exacerbating recovery pain or leading to bowel obstructions. Maintaining serosal integrity through minimally invasive techniques and anti-inflammatory protocols supports smoother post-surgical outcomes. Understanding the role of the serosa during digestive interventions reveals its underappreciated contribution to surgical success.

4. Are there any neurological diseases that can trace their origins to dysfunction in the layers of gut?

Recent studies suggest that certain neurodegenerative diseases may be linked to early dysfunction in the layers of gut tissue. For instance, alpha-synuclein—associated with Parkinson’s disease—has been found in the enteric nervous system, particularly within the submucosa and muscularis externa. This has prompted speculation that pathological changes in the layers GI tract may precede central nervous system involvement. Alterations in the wall of the stomach muscle tissue type, accompanied by abnormal motility, often appear before motor symptoms in Parkinson’s patients. These insights may pave the way for gut-based biomarkers and early interventions in neurological disease.

5. How does aging affect the regenerative ability of the layers of the digestive system?

Aging impacts each of the layers of the digestive system in complex ways. The mucosa thins over time, making it more susceptible to ulceration and delayed healing. Submucosal circulation declines, impairing immune response and nutrient absorption, which can exacerbate deficiencies that affect mental clarity and mood. The elasticity and contractility of the wall of the stomach muscle tissue type also deteriorate, contributing to slowed motility and constipation. Even the serosa becomes less efficient at lubricating gut surfaces, increasing friction and the likelihood of inflammatory adhesions. These age-related changes highlight the need for tailored nutritional and therapeutic interventions across the layers of gut health.

6. Could gut microbiome imbalances manifest differently depending on which layer is compromised?

Absolutely, the effects of microbiome disruption can vary depending on the affected layer of the digestive system. If the mucosal layer is compromised, pathogenic bacteria may directly interact with immune cells, triggering inflammation and increasing systemic permeability. In contrast, disturbances in the submucosa may alter neural signaling and nutrient transport, leading to subtler symptoms like mood fluctuations or fatigue. In the muscularis externa, microbial metabolites can influence peristalsis by acting on the enteric nervous system, particularly where the wall of the stomach muscle tissue type is already vulnerable. Even the serosa function in digestive system problems can be indirectly affected by microbiota-induced inflammation spreading through tissue layers. Thus, microbiome imbalance expresses itself differently depending on where the gut’s integrity is most fragile.

7. What lifestyle changes best support the structural resilience of the layers GI tract?

Lifestyle plays a pivotal role in preserving the structural and functional health of the layers GI tract. Regular exercise improves vascular flow to the submucosa and promotes healthy peristalsis in the muscularis externa. Stress-reducing activities such as yoga and mindfulness help stabilize the enteric nervous system, minimizing wear and tear on the wall of the stomach muscle tissue type. Nutritionally, diets high in fermented foods, polyphenols, and omega-3 fatty acids bolster mucosal immunity and reduce inflammation that can reach the serosa. Adequate sleep also enhances nightly repair processes across all layers of gut tissue. Together, these practices foster resilience from the innermost mucosa to the outermost serosa.

8. How do autoimmune conditions uniquely affect each layer of the digestive system?

Autoimmune disorders often exhibit layer-specific pathology within the digestive system. In conditions like celiac disease, the immune system targets the mucosa, flattening villi and impairing nutrient absorption. Crohn’s disease, on the other hand, can extend inflammation from the mucosa through to the serosa, severely compromising all layers of gut structure. The wall of the stomach muscle tissue type may become thickened and rigid in chronic cases, impairing motility. The submucosa often exhibits lymphoid hyperplasia and fibrosis in response to chronic immune activation. These insights underscore the importance of diagnosing how deeply each autoimmune condition penetrates the layers of gut anatomy.

9. Are there early warning signs that suggest structural degradation in the gut layers before symptoms become severe?

Early signs of structural compromise in the layers of digestive system often present subtly. Recurrent bloating, changes in stool consistency, or unexplained fatigue may indicate mucosal barrier dysfunction. A gradual decline in appetite or unexplained weight loss could signal impaired absorption within the submucosa. Discomfort after eating or erratic digestive timing may point to weakening in the wall of the stomach muscle tissue type. Meanwhile, lingering abdominal pain or sensitivity during movement may reflect early serosa involvement. Recognizing these signals allows for early intervention, potentially preventing the progression to more serious digestive and mental health issues.

10. How might advances in imaging or diagnostics improve our understanding of the layers of gut in the future?

Technological advancements are revolutionizing how we visualize and interpret the layers GI tract. High-resolution endoscopy and confocal laser endomicroscopy now allow for real-time visualization of mucosal and submucosal health. Diffusion tensor imaging may one day map enteric neural circuits embedded within the wall of the stomach muscle tissue type. Non-invasive biomarkers are also being developed to detect inflammation or fibrosis in the serosa function in digestive system problems, which have historically been hard to assess. These innovations will help clinicians detect early degeneration in the layers of gut tissue and implement more targeted, preventive care before irreversible damage occurs.

The Interdependence of Digestive Layers and Mental Health: Final Reflections

The journey through the digestive tract is not merely one of food processing but of immune modulation, neurological signaling, and emotional balance. Each of the layers of the digestive system—from the metabolically vibrant mucosa to the friction-reducing serosa—plays a distinct and indispensable role in maintaining gut health and influencing the mind. Whether we consider the muscular contractions enabled by the wall of the stomach muscle tissue type or the role of the serosa function in digestive system problems, it becomes clear that anatomical integrity is inseparable from psychological well-being.

As science continues to validate the gut-brain connection, attention must shift toward preserving the integrity of the layers of gut tissue through nutrition, lifestyle, and integrative medicine. Understanding the layers GI tract architecture and function offers a roadmap for restoring not just digestive function but also emotional and cognitive resilience. In a world where both mental and gastrointestinal disorders are rising, this holistic, anatomically informed approach may be one of the most powerful tools we have for reclaiming health from the inside out.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out

Further Reading:

What is the gut-brain connection?

Impacts of Gut Bacteria on Human Health and Diseases

Gut Health is Key to Your Mental Health at Work

Disclaimer

The information contained in this article is provided for general informational purposes only and is not intended to serve as medical, legal, or professional advice. While Health11News strives to present accurate, up-to-date, and reliable content, no warranty or guarantee, expressed or implied, is made regarding the completeness, accuracy, or adequacy of the information provided. Readers are strongly advised to seek the guidance of a qualified healthcare provider or other relevant professionals before acting on any information contained in this article. Health11News, its authors, editors, and contributors expressly disclaim any liability for any damages, losses, or consequences arising directly or indirectly from the use, interpretation, or reliance on any information presented herein. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of Health11News.