Feeding and nourishing a loved one with dementia can be one of the most emotionally challenging experiences a caregiver will ever face. Among the many difficult behavioral changes that arise in the progression of dementia, eating problems are among the most distressing and complex. Families often ask, with deep concern, “Why do dementia patients stop eating?” This is not simply a question of appetite or preference; rather, it is a multidimensional issue involving brain function, emotional well-being, and environmental factors. Addressing dementia and eating problems requires not only compassion but also a nuanced understanding of how neurological decline impacts daily life.

You may also like: How to Prevent Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease Naturally: Expert-Backed Strategies to Reduce Your Risk Through Lifestyle and Diet

Understanding Why Dementia Impacts Eating Habits

As dementia progresses, cognitive and physical changes can drastically alter a person’s relationship with food. The type of dementia dealing with the 5 food fornication forgetfulness pattern, a phrase capturing the interplay of memory loss, food aversion, and behavioral disruption, can make mealtimes an overwhelming experience. For many, eating becomes confusing, exhausting, or even frightening. In Alzheimer’s disease, for example, a person may forget how to use utensils or be unable to recognize food on their plate. In frontotemporal dementia, changes in behavior and personality may cause a dementia sufferer to overeat certain types of food or completely reject others. Meanwhile, vascular dementia and eating problems often stem from damage to brain regions responsible for appetite regulation, motor coordination, or sensory processing.

The issue of a dementia patient not eating is rarely caused by a single factor. Instead, it may reflect a cascade of overlapping problems: a diminished sense of taste or smell, physical discomfort while chewing or swallowing, gastrointestinal issues, or even a bad prior experience with food that now triggers anxiety. In these cases, dementia effects with bad experience with meals can profoundly shape future eating behavior. Someone who once loved pasta may suddenly reject it because they associate it with choking or nausea, even if they can no longer articulate why.

How Appetite and Hunger Cues Are Disrupted by Dementia

In a healthy individual, the sensation of hunger emerges from a finely tuned interaction between the brain and the body. However, dementia disrupts this system in several ways. The hypothalamus, which regulates hunger and satiety, may be impaired. Additionally, dementia and appetite loss are often linked to changes in mood or mental clarity. Depression, common in early and moderate dementia, may cause individuals to lose interest in eating altogether. The phrase “dementia and lack of appetite” captures just one dimension of a broader problem, where physiological, psychological, and environmental factors interact.

Some caregivers notice a phenomenon of dementia and eating habits shifting drastically. A once health-conscious individual may suddenly crave sweets or become disinterested in balanced meals. Others may repeatedly ask for food but only pick at their plate when it arrives. In certain types of dementia dealing with the 5 food fornication forgetfulness pattern, patients may even forget that they have already eaten or that the food before them is safe to consume. These changes are not simply forgetfulness; they are rooted in deep alterations in how the brain processes hunger, pleasure, and recognition.

Why Do Dementia Patients Not Want to Eat?

Understanding why dementia patients do not want to eat involves exploring both emotional and physical dimensions. On the emotional side, mealtimes can provoke anxiety if the person with dementia no longer understands the setting or the expectations. Imagine the confusion of being presented with a meal that looks unfamiliar or being asked to sit and eat in a noisy, overstimulating environment. These factors can reinforce dementia and eating issues, particularly when individuals feel pressured or judged by well-meaning loved ones.

On the physical side, many dementia sufferers develop medical issues that interfere with eating. Poor dental hygiene, undiagnosed oral infections, or ill-fitting dentures can make chewing painful. Meanwhile, some medications prescribed to manage dementia symptoms may suppress appetite or cause nausea, leading to a cycle of dementia and loss of appetite that becomes hard to reverse. As the disease progresses, swallowing difficulties (dysphagia) become more common, adding yet another layer to the complex picture of dementia and food challenges.

When Dementia Patients Stop Eating Entirely

There is perhaps no more alarming milestone for caregivers than when dementia patients stop eating altogether. This typically occurs in advanced stages of the disease and is often a sign that the body is shutting down. However, it is not always immediately clear when this stage has been reached. Families may initially interpret the behavior as stubbornness or depression, not realizing that swallowing has become difficult or that hunger signals no longer register. The phrase “when dementia patients stop eating” becomes a reality that is both heartbreaking and medically significant.

During this time, caregivers and healthcare professionals must navigate emotionally charged decisions. Should artificial feeding be introduced? Is the person experiencing discomfort or pain? Can dementia cause weight loss at this stage, and if so, is it reversible? The answer varies from case to case, and compassionate, informed guidance is essential. It is important to remember that weight loss in dementia is often multifactorial, linked not only to reduced food intake but also to muscle wasting, increased caloric needs due to agitation, and metabolic changes.

The Role of Vascular Dementia in Eating Problems

Among the various forms of dementia, vascular dementia poses a particularly challenging set of issues related to eating. Because this condition often results from strokes or chronic blood flow disruptions, it can affect highly specific areas of the brain. When those areas include the thalamus, basal ganglia, or frontal lobes, appetite regulation and motor control are directly impacted. As a result, vascular dementia and eating problems can manifest not only as lack of appetite but also as difficulties in chewing, swallowing, or even recognizing food.

Patients with vascular dementia are also more likely to experience coexisting health conditions like hypertension, diabetes, or heart disease, which may require dietary restrictions. This can create additional complications, as caregivers struggle to offer food for dementia sufferers that meets medical requirements while still being appealing. The sensory deficits common in vascular dementia, such as diminished taste or smell, further reduce appetite. For individuals who have suffered a stroke, paralysis on one side of the body may make it physically difficult to bring food to the mouth, further reinforcing the cycle of dementia not eating.

Emotional Associations: Dementia Effects with Bad Experience with Meals

The emotional landscape of dementia and food cannot be overstated. Many people with dementia carry emotional memories of mealtimes that shape their behavior even when cognitive awareness fades. For example, a person who once choked on a particular texture may begin refusing all foods with a similar consistency. This phenomenon reflects dementia effects with bad experience with meals, where trauma—whether remembered or not—becomes a behavioral obstacle.

Additionally, caregivers may inadvertently reinforce negative associations. Repeated coaxing, arguing, or insisting can cause a dementia sufferer to feel overwhelmed or ashamed. When eating becomes a battleground, the emotional toll on both parties deepens. Creating a calm, soothing mealtime environment, free from stress and distraction, is a key strategy in managing dementia and eating problems. Offering familiar foods served in a consistent setting can help reestablish positive associations with meals.

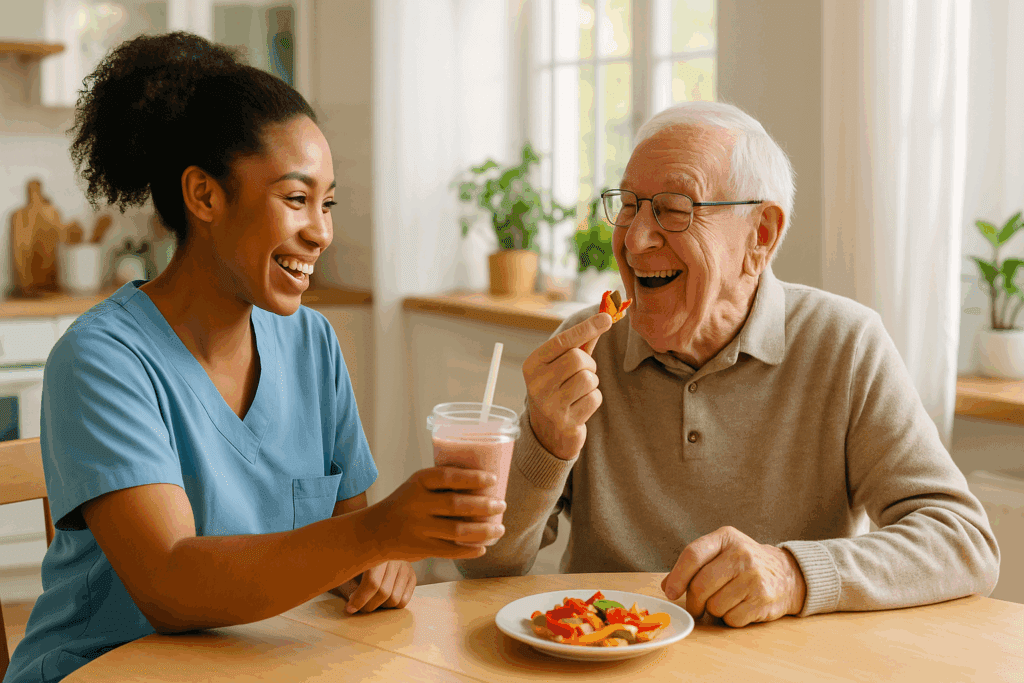

Navigating the Challenge: How to Get Dementia Patients to Eat

Caregivers often find themselves asking not just why but how to get dementia patients to eat. This question demands both practical strategies and emotional sensitivity. One of the most effective approaches involves tailoring meals to the person’s current abilities and preferences. Finger foods, for example, can be easier for someone who struggles with utensils. Brightly colored plates may help with visual recognition, while small, frequent meals may be more successful than three large ones.

Variety and routine also play a role in supporting consistent eating habits. Caregivers should pay close attention to patterns: Is the person more alert in the morning? Do they respond better to sweet or savory flavors? Experimentation, within reason, can help uncover what works. At the same time, caregivers must stay flexible and nonjudgmental. It is not uncommon for dementia and eating habits to change from day to day. Patience is essential, as is the willingness to adapt without pressure.

It is equally important to consider the environment. A peaceful, uncluttered dining space with minimal noise can ease anxiety and improve focus. Music that the person finds soothing may enhance the experience. Sitting together and sharing the meal can also create a sense of social connection that encourages eating. These techniques can be especially helpful for the dementia patient not eating due to emotional distress or confusion.

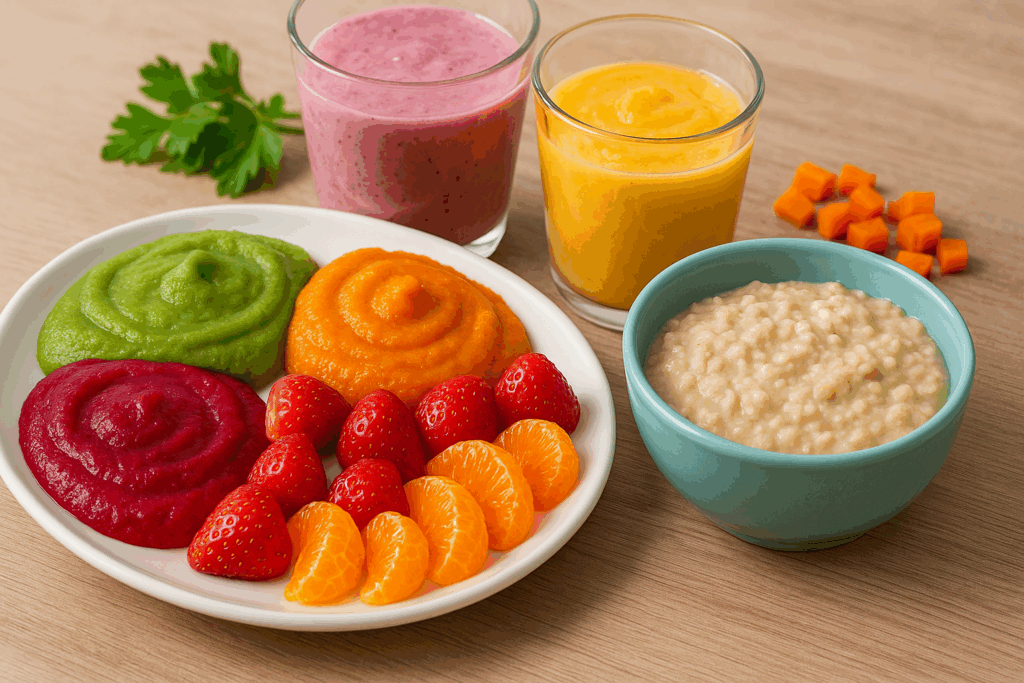

Choosing Nutrient-Rich and Appealing Food for Dementia Sufferers

Selecting the right food for dementia sufferers requires balancing nutrition with palatability. Foods should be easy to chew and swallow, nutrient-dense, and visually appealing. Smooth textures like scrambled eggs, yogurt, oatmeal, and pureed vegetables can be both safe and comforting. At the same time, it’s important to avoid monotony. Dementia and eating problems may be exacerbated by boredom or sensory deprivation, so incorporating different flavors, colors, and aromas can stimulate appetite.

Fortified foods and high-calorie snacks can help counteract dementia and weight loss. Smoothies made with nut butters, avocados, and protein powders are often well tolerated. For individuals who crave sweets, naturally sweet options like fruit or honey-sweetened custards can offer both enjoyment and nutrition. However, caregivers must remain vigilant to avoid sugar overload, especially in individuals with coexisting diabetes.

Hydration should also be a central focus. Many dementia patients become dehydrated due to reduced thirst perception or reluctance to drink. Offering water-rich foods, flavored water, or herbal teas can support fluid intake. When combined with a nutrient-rich diet, these measures help stabilize mood, energy, and cognitive function, supporting well-being even in the face of advanced disease.

Addressing the Deeper Question: Why Do People with Dementia Stop Eating?

At its core, the question of why people with dementia stop eating is about more than food. It reflects the complex interplay between neurological damage, psychological shifts, environmental stressors, and physical limitations. In some cases, the cessation of eating is a sign of disease progression. In others, it is a response to reversible factors like medication side effects, infections, or emotional distress.

Understanding dementia and eating problems requires a holistic lens. Families and caregivers must be prepared to evaluate each individual’s unique needs and to adjust expectations accordingly. This is especially true in the case of dementia and lack of appetite, which may not respond to coaxing but can improve with changes in routine, food presentation, or emotional support. When interventions fail, it is crucial to have open, compassionate conversations with healthcare providers about goals of care, comfort, and dignity.

Supporting Caregivers: Emotional and Practical Strategies

The burden of supporting a dementia patient not eating falls heavily on caregivers. It is important for families to know they are not alone and that resources exist to guide and support them. Professional guidance from geriatricians, speech-language pathologists, dietitians, and occupational therapists can provide tailored solutions. Community support groups and counseling services can also help caregivers cope with the emotional toll of navigating dementia and eating issues day after day.

Self-care must be a priority for caregivers as well. The relentless stress of trying to figure out how to get dementia patients to eat can lead to burnout, resentment, or guilt. Taking breaks, asking for help, and maintaining social connections can help caregivers preserve their own health and perspective. Education is equally powerful. The more caregivers understand the underlying mechanisms of dementia and eating habits, the better equipped they are to respond with empathy rather than frustration.

Finding Dignity in the Final Stages of Dementia

As dementia reaches its final stages, decisions about nutrition often become decisions about comfort and dignity. When dementia patients stop eating, families are faced with questions that touch on ethics, medicine, and spirituality. Is it right to force feeding? What is the goal of continuing to offer food? How can we ensure that our loved one is not suffering?

There are no easy answers, but there are compassionate paths forward. Palliative care teams can help families navigate these crossroads with grace. Their expertise in comfort-focused care offers a model for respecting the individual’s humanity even when cognition has declined. Ultimately, honoring the wishes, comfort, and dignity of the person with dementia should be the guiding principle.

Frequently Asked Questions: Dementia and Eating Challenges

1. What are some lesser-known reasons why a dementia patient might suddenly refuse food they’ve previously enjoyed?

One overlooked reason a dementia patient not eating may stem from subtle environmental changes, such as lighting, table settings, or background noise that disrupts sensory perception. As dementia alters visual-spatial awareness, even shadows on a plate or the color of the dish can create confusion. Another factor involves unspoken discomfort—constipation, dental pain, or unrecognized acid reflux can significantly impact willingness to eat. Furthermore, dementia effects with bad experience with meals may linger in ways the person cannot articulate. If a specific meal caused nausea or choking in the past, the brain may develop a subconscious aversion. This dynamic is especially complicated in cases of the type of dementia dealing with the 5 food fornication forgetfulness pattern, where memory and sensory feedback loops are impaired.

2. How can caregivers distinguish between a temporary eating disruption and a serious sign that dementia patients are entering a later stage?

Distinguishing between short-term eating issues and deeper medical decline often requires close observation and professional input. When dementia and eating problems persist beyond a few days and coincide with other behavioral changes like increased sleep, reduced mobility, or social withdrawal, this may indicate progression toward end-stage disease. Medical evaluations can help rule out treatable causes such as infections or medication side effects. However, when dementia patients stop eating and no physical cause is found, it could signify neurological decline affecting appetite regulation or swallowing reflexes. This is particularly concerning in vascular dementia and eating problems, where sudden neurological events like mini-strokes may disrupt feeding behaviors dramatically.

3. Are there any psychological therapies that help with dementia and eating habits?

Yes, emerging therapeutic approaches can support dementia and eating issues through psychological and behavioral strategies. Reminiscence therapy, which uses past experiences to stimulate memory, can sometimes reconnect individuals to positive food memories. Music therapy at mealtimes may enhance mood and reduce anxiety, creating an emotional setting conducive to eating. Occupational therapists may also use simulation-based interventions to retrain hand-eye coordination and utensil use. These tools can be especially useful when a dementia sufferer not eating is related to loss of procedural memory rather than appetite. Additionally, cognitive behavioral approaches adapted for dementia can reduce food-related stress by breaking negative associations formed from dementia effects with bad experience with meals.

4. What innovative tools or technologies are helping caregivers manage dementia and food challenges?

New technologies are playing a transformative role in managing dementia and food issues. Smart dining utensils that detect tremors can help individuals maintain independence during meals. Color-contrasted plates and AI-powered apps that track nutritional intake offer caregivers real-time insights. Some care homes now use adaptive feeding systems that respond to a person’s movement and pace, reducing stress when a dementia patient not eating struggles with coordination. These innovations are particularly beneficial in cases involving the type of dementia dealing with the 5 food fornication forgetfulness pattern, where behavioral unpredictability complicates traditional caregiving. Also, sensory-stimulating food packaging that incorporates familiar scents can reignite interest in eating by tapping into the brain’s olfactory memory centers.

5. How can families navigate ethical dilemmas when dementia patients stop eating entirely?

When dementia patients stop eating altogether, families are often faced with emotionally fraught decisions about artificial nutrition and end-of-life care. It is essential to differentiate between a dementia and appetite loss that is transient and one that reflects terminal decline. Ethical guidance from palliative care specialists can help clarify when interventions support quality of life versus prolong suffering. For example, when dementia and loss of appetite are accompanied by swallowing difficulties, tube feeding might not improve outcomes and may increase distress. Families must also consider the patient’s previously stated wishes and cultural beliefs, especially when exploring how to get dementia patients to eat in a compassionate, non-invasive way. Respect for autonomy, dignity, and comfort should always guide decision-making.

6. What role do cultural and spiritual beliefs play in dementia and eating problems?

Cultural and spiritual frameworks often shape how families approach dementia and food. In some cultures, refusal to eat is seen as a spiritual transition, rather than a medical emergency, influencing how caregivers interpret dementia and lack of appetite. Religious practices may also affect which foods are considered appropriate or sacred, impacting how food for dementia sufferers is selected and served. Certain rituals, like praying before meals or listening to hymns, may re-establish a sense of familiarity and comfort. Moreover, understanding cultural interpretations of why do people with dementia stop eating can reduce caregiver anxiety and help contextualize behavior. Integrating cultural awareness into feeding routines is a powerful, often underutilized, strategy to support both patient and family well-being.

7. Can past trauma or emotional events influence dementia and eating behavior later in life?

Absolutely. Emotional trauma, especially if food-related, can resurface during dementia, influencing current eating behaviors in unexpected ways. This phenomenon illustrates how dementia effects with bad experience with meals may emerge from long-forgotten episodes. For example, individuals who experienced food scarcity or force-feeding in childhood may reject meals when autonomy is compromised. In some cases, even watching others eat in a communal setting can trigger feelings of anxiety or vulnerability. Understanding why dementia patients not want to eat sometimes means exploring deep-seated emotional patterns rather than focusing solely on physical health. Therapists with expertise in trauma-informed dementia care can provide insights and suggest practical ways to create emotionally safe mealtimes.

8. What foods are best tolerated when a dementia patient not eating has become a chronic concern?

When addressing chronic refusal to eat, the focus should shift toward high-nutrient, low-effort meals that appeal to the senses. Foods like mashed sweet potatoes, banana-based puddings, soft cheeses, and broths enriched with protein powders offer nourishment without chewing difficulty. Finger foods also empower autonomy, especially in cases of the type of dementia dealing with the 5 food fornication forgetfulness pattern, where utensils are confusing. It’s vital to rotate these selections regularly to counteract taste fatigue, which often exacerbates dementia and eating problems. Above all, food for dementia sufferers must be pleasurable, not just nutritious, to promote consistent intake and support emotional well-being.

9. How do you support hydration when dementia and loss of appetite also lead to reduced fluid intake?

Hydration strategies should be integrated seamlessly into daily routines. Offering fruits like watermelon, cucumber, or oranges provides both fluid and sensory stimulation. Popsicles made from herbal teas or juice can be a playful and refreshing way to encourage hydration. Specially thickened liquids may be needed in cases where swallowing is impaired—a frequent issue in vascular dementia and eating problems. Caregivers might also consider visual aids or sound cues, like a bell, to establish hydration reminders, which can be particularly helpful when dementia and eating habits follow rigid or repetitive patterns. Ultimately, maintaining hydration is just as critical as caloric intake in preserving energy and mental clarity.

10. What proactive strategies can help prevent dementia and eating problems from becoming severe?

Early intervention is key to preventing escalation. Begin by creating a food journal to track likes, dislikes, and behavioral patterns around meals. This helps identify emerging dementia and eating issues before they become entrenched. Regular dental checkups, medication reviews, and discussions with a dietitian can also mitigate risk factors. Incorporating mealtime into familiar routines, such as setting the table together or preparing food as a shared activity, reinforces consistency and engagement. Most importantly, addressing the early signs of dementia not eating with empathy rather than urgency sets the tone for long-term nutritional success and emotional resilience for both patient and caregiver.

Conclusion: Supporting Nutrition, Well-Being, and Compassion in Dementia Care

In the journey of caring for someone with dementia, few challenges are as emotionally charged as feeding. The question of why do dementia patients stop eating opens the door to a deeper understanding of the brain, behavior, and the profound changes this disease brings. From the early signs of appetite changes to the advanced stages when dementia patients stop eating entirely, each phase requires empathy, patience, and informed care.

Recognizing the wide range of dementia and eating problems—from dementia and lack of appetite to the effects of bad meal experiences—allows caregivers to tailor their approach with both science and compassion. Whether navigating the complexities of vascular dementia and eating problems or experimenting with different types of food for dementia sufferers, the goal remains the same: to nourish not just the body, but the spirit as well.

By integrating practical strategies for how to get dementia patients to eat, understanding the emotional roots behind why dementia patients not want to eat, and responding sensitively to changing dementia and eating habits, caregivers can make a meaningful difference. The path is never easy, but with knowledge, support, and love, it is possible to create moments of comfort and connection, even in the most challenging of circumstances.

Further Reading:

What to Do If a Person with Dementia Is Not Eating

Eating Behaviors and Dietary Changes in Patients With Dementia