In the delicate and complex landscape of cognitive disorders, few questions are as emotionally fraught or clinically nuanced as do people with dementia know they have it. This question touches on issues of self-awareness, identity, memory, and emotional regulation, and challenges caregivers, clinicians, and families alike to navigate an often confusing intersection of neuroscience and human experience. The answer is far from straightforward. Dementia, in all its forms, affects people differently, and the degree to which individuals retain awareness of their own condition varies widely. For some, insight remains surprisingly intact during the early stages, while for others, denial or a complete lack of awareness—clinically termed anosognosia—takes hold early and deepens over time.

The very nature of dementia, particularly Alzheimer’s disease, involves progressive damage to the brain’s frontal and parietal lobes, which are crucial to self-reflection and memory integration. As these regions deteriorate, so too does the individual’s ability to recognize deficits in their own thinking or behavior. However, in the early stages, many people with dementia do indeed express awareness of their memory problems or cognitive lapses. This insight can be deeply distressing, giving rise to anxiety, frustration, and depression. Thus, the question of do people with dementia know they have it is not only a medical inquiry but also a psychological and existential one.

You may also like: How to Prevent Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease Naturally: Expert-Backed Strategies to Reduce Your Risk Through Lifestyle and Diet

Understanding Self-Awareness in Dementia: A Neurocognitive Perspective

To understand whether people with dementia know they have it, we must first consider the neuroanatomical and psychological underpinnings of self-awareness. Self-awareness is a complex cognitive function that requires integration of memory, executive functioning, and emotional processing. These capacities are largely governed by the prefrontal cortex and its connections with other brain regions. When these circuits are disrupted, as they often are in neurodegenerative diseases, the individual’s insight into their own condition can become impaired.

Studies using functional MRI and PET scans reveal that individuals with dementia often show reduced activation in areas associated with self-monitoring and error recognition. These findings correlate with clinical observations where patients deny or minimize their impairments, even when faced with clear evidence. Yet, this lack of insight is not uniform. In cases of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or early-stage dementia, many patients retain the ability to observe changes in their memory, judgment, or language skills. They may express concern, seek medical help, or even make adjustments to their daily routines to compensate.

In contrast, as dementia progresses, the likelihood of a person retaining accurate self-awareness decreases. The question “do people with dementia know they have dementia?” becomes less about a simple yes or no and more about the progression of the disease, the individual’s personality, their psychological defenses, and the specific areas of the brain that are affected. Anosognosia, or lack of awareness, is especially common in moderate to severe stages, where individuals may outright deny having any problems at all. This phenomenon is not rooted in stubbornness or pride but in a neurological inability to process one’s deficits.

Do People with Dementia Know They Are Confused? Insights into Moment-to-Moment Awareness

Another dimension of this inquiry involves the real-time experiences of individuals with dementia. Does a person with dementia know they are confused? The answer to this question reveals an important layer of complexity in understanding how dementia impacts consciousness. In many cases, people with early or even moderate dementia do exhibit moments of clarity in which they acknowledge their disorientation. They might say, “I can’t remember what I was doing,” or “I feel mixed up today.”

These acknowledgments show that some form of situational awareness is still present. However, these moments can be fleeting and inconsistent. Over time, as dementia progresses and short-term memory deteriorates further, people may lose the capacity to retain even brief periods of lucidity. This creates a paradoxical experience where the individual might feel uneasy, anxious, or irritable without understanding why. Emotional distress can arise from a subconscious recognition that something is wrong, even when the individual cannot articulate the specifics of their confusion.

In some cases, dementia patients exhibit behaviors that suggest a rudimentary awareness of their confusion. They may withdraw from social situations, avoid tasks they once mastered, or become irritable when faced with challenges that highlight their cognitive decline. These behaviors often speak louder than words, indicating that while the person may not explicitly say they are confused, their actions reveal an inner struggle with disorientation. Thus, the question “does a person with dementia know they are confused” is best answered with an acknowledgment of variability—some do, some don’t, and many fluctuate between the two states.

What Do Dementia Patients Think About? The Internal World of Cognitive Decline

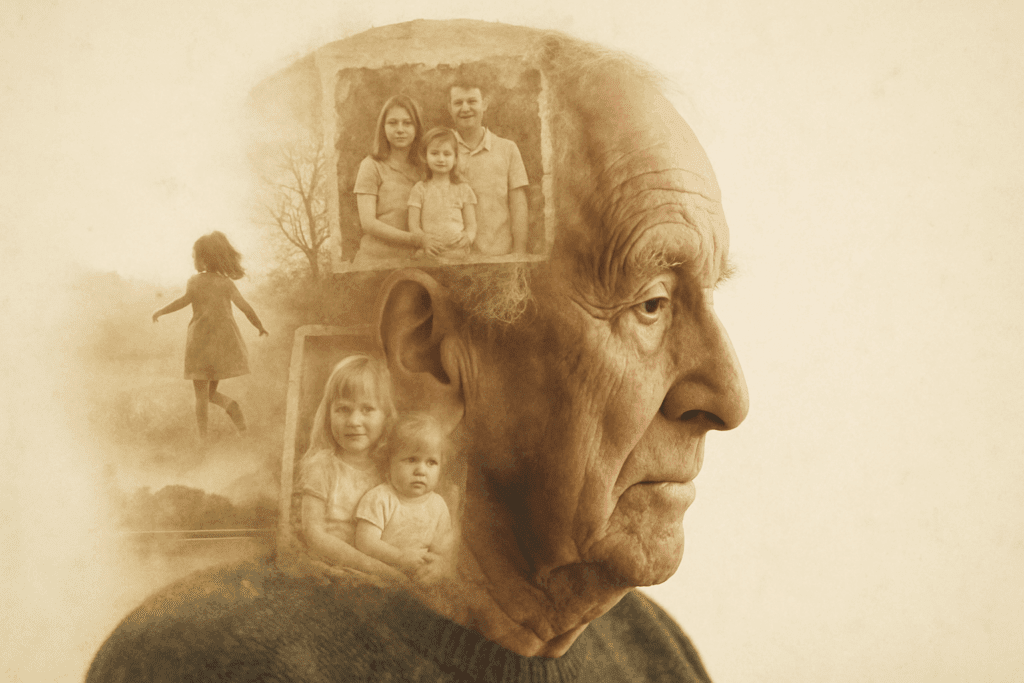

Perhaps one of the most intriguing and tender aspects of dementia research is the exploration of what dementia patients think about. Understanding this inner world is essential for anyone seeking to connect meaningfully with someone living with cognitive decline. Contrary to common assumptions, people with dementia are not simply blank slates or lost in a perpetual fog. Even in advanced stages, they may experience moments of emotional resonance, sensory awareness, and personal memory.

In earlier stages, individuals with dementia often reflect on their fears, losses, and confusion. They may worry about becoming a burden, forgetting loved ones, or losing independence. These thoughts are not only common but deeply human. As the disease progresses, thought content may become more fragmented, looping, or disconnected from present reality. Some individuals revisit early childhood memories or become fixated on repetitive concerns. Others may express confusion about time, place, or relationships but still retain a sense of self anchored in emotional experiences.

Interestingly, music, familiar routines, and tactile stimuli can evoke strong emotional reactions, suggesting that certain types of memory and cognition remain intact even when logical reasoning and language falter. This preservation of implicit memory highlights the richness of the inner world of dementia patients. Thus, when we ask, “what do dementia patients think about?” the answer is as layered and multifaceted as the individual themselves. They think about their past, their feelings, their family, and sometimes, simply about trying to make sense of a confusing reality.

The Role of Denial, Defense Mechanisms, and Psychological Coping

Another important angle in understanding whether people with dementia know they have it lies in the realm of psychological coping. Denial is a common and often adaptive defense mechanism in the face of overwhelming cognitive or emotional stress. In early dementia, some individuals may demonstrate partial awareness but simultaneously engage in denial to manage the emotional burden. This can manifest as minimizing symptoms, attributing memory lapses to stress or age, or avoiding discussions about their condition.

For caregivers and clinicians, it can be challenging to distinguish between true neurological anosognosia and psychological denial. Both result in an apparent lack of insight, but the underlying mechanisms differ. Anosognosia stems from brain damage, particularly to the right hemisphere or prefrontal cortex. Denial, by contrast, is an active—albeit unconscious—process of emotional regulation. Understanding the difference can help in tailoring communication strategies and support systems.

It’s also important to consider the individual’s personality, life history, and coping style. Some people are naturally introspective and open to discussing health concerns, while others have always avoided confronting difficult truths. These traits don’t disappear with dementia; rather, they shape how the disease is experienced and interpreted. Thus, when exploring the question “does a person with dementia know they have it,” we must consider not only neurological and cognitive factors but also psychological resilience and defense mechanisms.

Caregiver Challenges and Communication Strategies When Insight Varies

For caregivers, the variability in a dementia patient’s insight presents a daily challenge. Communication becomes an evolving puzzle, requiring patience, flexibility, and a deep understanding of the individual’s cognitive and emotional state. When people with dementia do know they have dementia, they may experience grief, anxiety, or depression, which requires sensitivity and validation. When they do not, efforts to confront or correct them may provoke confusion, frustration, or even aggression.

This dynamic forces caregivers to walk a fine line between honesty and compassion. In some cases, therapeutic fibbing or redirecting may be necessary to reduce distress. Rather than insisting on factual correction, caregivers can focus on emotional validation—acknowledging the person’s feelings and redirecting their attention to comforting or familiar topics. This approach respects the reality of the dementia patient without needlessly challenging their cognitive limitations.

Moreover, when a caregiver understands that a person’s lack of insight is not intentional but a symptom of brain disease, it can reduce interpersonal tension and prevent caregiver burnout. Support groups, professional counseling, and caregiver education can provide crucial tools for navigating these emotionally intense scenarios. Thus, the issue of whether people with dementia know they have it extends beyond the individual to include the psychological wellbeing of those who love and care for them.

Anosognosia Versus Partial Insight: A Spectrum of Awareness in Dementia

An essential concept in the discussion of dementia-related self-awareness is the idea of a spectrum, ranging from full insight to complete unawareness. This spectrum helps explain the wide variability in responses to the question “do people with dementia know they have dementia.” Anosognosia, a clinical term for unawareness of one’s own illness, is common in middle to late-stage dementia and can affect different cognitive domains differently. For example, a person might recognize that their memory is impaired but deny any problems with judgment or spatial awareness.

Research suggests that insight is more likely to be retained when the damage to the prefrontal cortex is less severe. Additionally, insight may be domain-specific, with some individuals demonstrating awareness of certain deficits but not others. This has implications for treatment adherence, safety planning, and care coordination. A person who recognizes their memory impairment is more likely to comply with medication regimens, accept help, and make informed decisions about their care.

Conversely, complete anosognosia poses significant risks. People may attempt to drive, manage finances, or refuse assistance, all while being unaware of their limitations. This not only endangers the individual but can place immense stress on families and care providers. Thus, identifying where a person falls on the spectrum of insight is critical for designing effective interventions.

Ethical Implications: Autonomy, Consent, and the Right to Not Know

The ethical implications of insight in dementia extend far beyond clinical care. They touch on questions of autonomy, consent, and even the right not to know. When individuals do know they have dementia, they may be able to make informed choices about their future, including advanced directives, financial planning, and end-of-life care. But when insight is absent, decision-making becomes more complex.

Families and healthcare providers must often grapple with questions about how much to disclose, when to intervene, and whether the person’s previous wishes still hold. In some cases, individuals explicitly express a desire not to know about a possible dementia diagnosis, preferring to live without that burden. Honoring such wishes, when cognitively possible, is a matter of respecting autonomy and human dignity.

On the flip side, ensuring informed consent for medical procedures or participation in clinical trials requires some level of cognitive insight. This creates a delicate balance between protecting the individual and preserving their rights. Thus, whether a person with dementia knows they have it has ethical, legal, and deeply personal consequences that must be considered with care and compassion.

FAQ: Understanding Dementia Awareness and Self-Insight in Patients

1. Can people with dementia be selectively aware of their symptoms?

Yes, it’s common for individuals with dementia to have a fragmented sense of self-awareness. Some may recognize memory loss but not acknowledge poor judgment or disorientation. This selective insight often depends on which parts of the brain are affected. For instance, when the prefrontal cortex is less compromised, a person might notice they’re forgetting names but still believe they can manage finances. So, when we ask “do people with dementia know they have it,” we need to recognize that awareness may be partial, selective, and influenced by both neurobiological changes and personality traits.

2. How does emotional awareness play into a dementia patient’s self-recognition?

Emotional awareness often remains intact longer than cognitive insight. A person may not verbalize, “I have dementia,” yet show signs of distress, sadness, or even embarrassment when they make mistakes or forget important details. These emotional cues offer valuable clues about how much someone grasps their condition on a subconscious level. While it’s possible to answer “do people with dementia know they have dementia” with a yes in emotional terms, that awareness may not always translate into verbal or intellectual acknowledgment. Caregivers can often interpret emotional signals more accurately than words alone.

3. What role do caregivers play in shaping how patients perceive their condition?

Caregivers serve as emotional mirrors and reality anchors for many individuals with dementia. Their tone, facial expressions, and responses to patient behavior can either reinforce or buffer a person’s awareness of cognitive decline. For example, if a caregiver consistently corrects or scolds a person, that may heighten confusion or shame, whereas gentle redirection may preserve dignity. Thus, in discussions about whether a person with dementia knows they have it, we must consider the relational environment. Often, the interaction style of those around the patient greatly influences how insight is expressed or suppressed.

4. Are there cultural differences in how dementia self-awareness is perceived or discussed?

Absolutely. In some cultures, cognitive decline is viewed as a normal part of aging and not labeled or discussed in clinical terms. In these contexts, even when people with dementia know they have it, they may avoid naming it or deny the diagnosis due to stigma or tradition. Conversely, cultures with high health literacy and open dialogue about mental health may facilitate earlier acknowledgment and acceptance. The question “do people with dementia know they have dementia” must therefore be evaluated not only through a neurological lens but also within sociocultural frameworks. Cultural context shapes both personal insight and public discussion.

5. How can we assess whether a person with dementia knows they are confused?

Subtle behavioral indicators can often answer the question, “does a person with dementia know they are confused?” For example, hesitation before speaking, avoiding decision-making, or seeking constant reassurance are signs of emerging confusion awareness. People might even verbalize discomfort by saying things like, “I’m not sure what’s happening,” without naming the cause as dementia. Clinicians often use specialized tools, such as discrepancy interviews or the Anosognosia Questionnaire, to explore self-perception. Still, informal observations during daily routines often provide the clearest insights into whether someone is consciously struggling with confusion.

6. Do dementia patients ever express awareness through creative or non-verbal means?

Yes, artistic expression, music, and even physical gestures can convey self-awareness in powerful ways. A person who struggles to articulate memory issues might draw a picture symbolizing loss or isolation, or hum a nostalgic tune linked to a lucid moment. These forms of communication can serve as emotional bridges when verbal faculties falter. When asking “what do dementia patients think about,” it’s crucial to remember that thoughts may be expressed symbolically rather than through logical speech. Tapping into creative outlets can reveal more about a person’s self-insight than traditional conversation.

7. What happens when a person fluctuates between awareness and unawareness?

Fluctuating insight is common and can be one of the most emotionally intense aspects for both the individual and their family. On one day, a person may articulate clearly, “Something is wrong with my brain,” and the next, deny any issues. This waxing and waning awareness can be linked to fatigue, illness, stress, or medication side effects. In such cases, asking “does a person with dementia know they have it” must include a time component—awareness today may not be present tomorrow. Supporting loved ones through these ups and downs requires adaptability and emotional resilience.

8. Can external cues help dementia patients recognize their own condition?

Sometimes, yes. Seeing memory aids, written notes, or even hearing consistent language from caregivers can trigger fleeting insight. For example, a memory calendar may remind someone that they’ve been forgetting things lately, helping them momentarily realize their cognitive challenges. These external prompts can answer the question “do people with dementia know they have it” in a contextual sense—they may not retain that awareness long-term but can access it briefly with reminders. However, too many cues or overly blunt reminders can also increase anxiety, so balance and personalization are key.

9. How does insight affect dementia care planning and long-term outcomes?

Insight plays a significant role in a person’s willingness to participate in care decisions. Individuals who acknowledge their condition are more likely to agree to advance directives, medication adherence, and supportive services. In contrast, when insight is lacking, families often face resistance or denial, complicating planning efforts. Understanding whether people with dementia know they have dementia allows healthcare providers to tailor approaches that match the patient’s cognitive readiness. Overestimating or underestimating this awareness can lead to frustration or ethical dilemmas around autonomy and consent.

10. Are there strategies to preserve or enhance insight in dementia patients?

While there is no guaranteed way to preserve insight indefinitely, certain strategies may help maintain it longer. Cognitive stimulation therapies, validation therapy, and reflective conversation techniques can help reinforce a sense of identity and orientation. Encouraging people to talk about their feelings, rather than just facts, can create safe spaces for awareness to emerge. Importantly, reinforcing dignity and agency can reduce emotional defenses that might otherwise block recognition. When exploring “what do dementia patients think about,” fostering reflective dialogue can yield surprising clarity, even late into the disease.

Conclusion: Navigating the Complex Reality of Dementia Insight

In the end, the question “do people with dementia know they have it” has no universal answer, but rather many deeply personal ones. Dementia is not a monolith; it is a complex, evolving condition that affects awareness, memory, and personality in varied and sometimes unpredictable ways. Some people retain a poignant, painful awareness of their decline, while others remain blissfully unaware, protected by the very damage the disease inflicts.

Understanding this reality is crucial for caregivers, clinicians, and society at large. It shapes how we communicate, how we plan care, and how we support both patients and their families through the dementia journey. Recognizing that the question “does a person with dementia know they have it” intersects with neurobiology, psychology, ethics, and emotion allows us to respond with greater empathy and effectiveness.

Ultimately, whether a person is aware of their condition or not, their experiences remain valid, their feelings remain real, and their dignity remains intact. In learning to see through the lens of their evolving awareness, we gain not only a deeper understanding of dementia but also a greater capacity for compassion, patience, and love.

Further Reading:

Self-awareness in Dementia: a Taxonomy of Processes, Overview of Findings, and Integrative Framework

Change in the psychological self in people living with dementia: A scoping review